After remaining interred for over a century in the Winterberg tunnel, the bodies of more than 270 German soldiers—once thought to be lost deep within the still-battle-scarred French landscape—have recently been discovered.

Located on the Chemin des Dames battlefront, the remains of the World War I soldiers were found, thanks in large part to a French father-and-son team Alain and Pierre Malinowski, the BBC reports.

Translated into English as the “Ladies Path,” Chemin des Dames acquired its name in the 18th century after it became a frequent travel route of the daughters of King Louis XV. Nearly 20 miles long, the road runs east to west between the Ailette river valley to the north and the Aisne river valley to the south.

Once an idyllic part of the French countryside, Chemin des Dames soon became “one the most blood-soaked swaths of land in Europe,” writes historian David T. Zabecki.

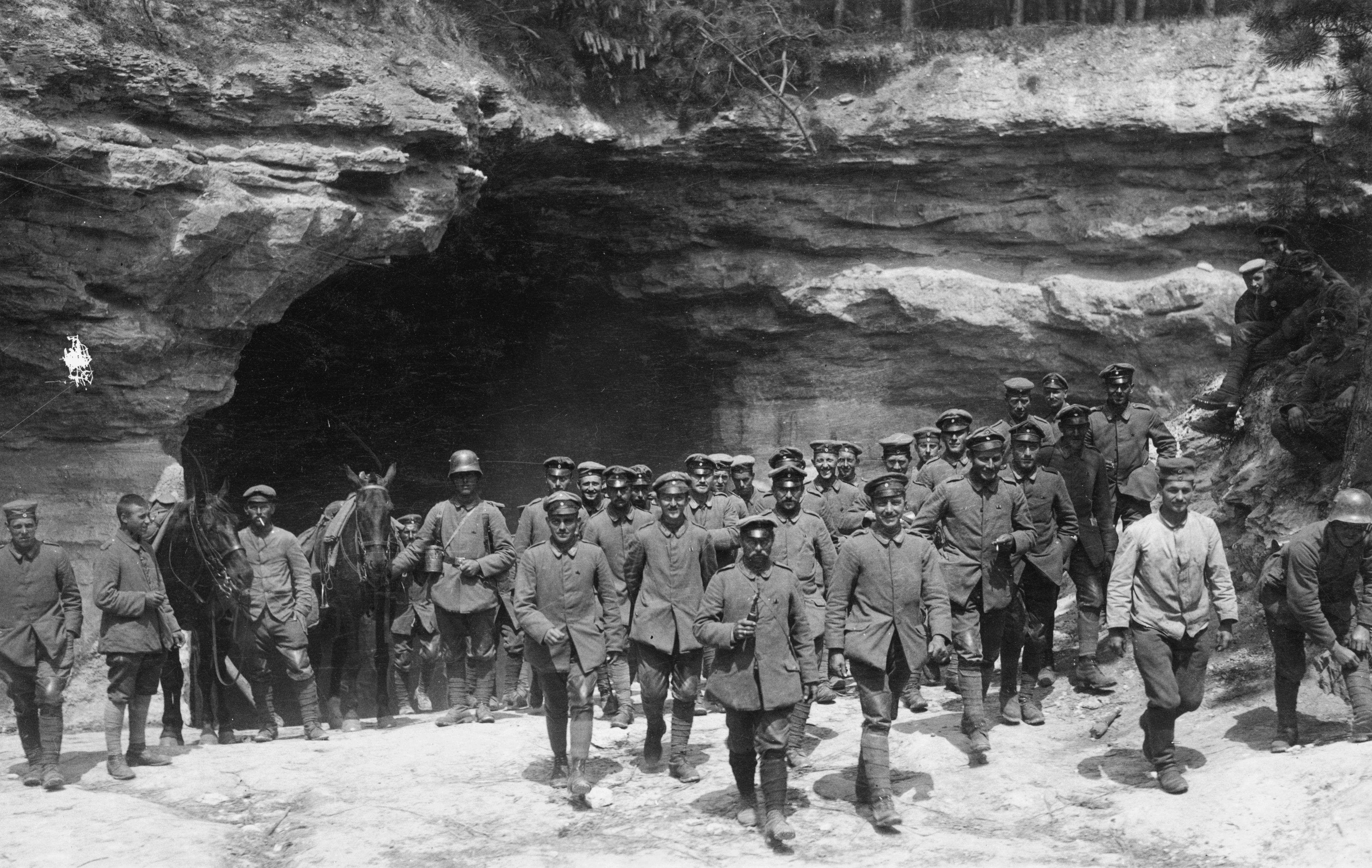

During World War I, the Allies and Germans fought three major battles along the Chemin des Dames. “The First Battle of the Aisne unfolded Sept. 13–28, 1914, as French and British forces pursued the withdrawing Germans after the First Battle of the Marne,” writes Zabecki. The Germans dug in behind the Aisne and occupied the northern high ground.

For more than two years the Germans held that strategic ridge, fending off all French counterattacks.

In a desperate bid to dislodge them in the spring of 1917, General Robert Nivelle, the French commander in chief, launched a massive offensive intended to break the stalemate along the Western Front.

Chemin des Dames and the surrounding planes were key to Nivelle’s battle plan. However, what was designed to be “the formula” that would splinter the Imperial German Army turned out to be one of the greatest disasters in French military history. Thanks to the Germans’ in-depth defensive system and extensive tunnel network, the French assault was stopped cold.

“By the time Nivelle halted the offensive five days later,” writes Zabecki, “the French army had sustained more than 120,000 casualties. French morale snapped, and the resulting widespread mutinies tore the French army apart, almost knocking France out of the war.”

Despite the crushing blow, the French launched an artillery bombardment towards the Winterberg tunnel as a final parting shot. At almost 1,000 feet long, the tunnel was all but invisible to French troops on the ground and helped to supply Germans in the frontline trenches. In an attempt to sever the line, the French sent up an observation balloon to properly sight the area.

On May 4, 1917, an on-target shell hit the entrance to the tunnel, sealing it off. Another French-lobbed shell managed to close off the exit. By doing so, more than 270 men from the 10th and 11th companies of the 111th Reserve Regiment became trapped inside.

Over the next six days, as the oxygen thinned, the soldiers began to asphyxiate or take their own lives to avoid suffocation. Others asked for a mercy kill.

According to the BBC, three men managed to survive long enough to be brought out by rescuers just a day before the crest was abandoned to the French.

One survivor, Karl Fisser, left an account for the regimental history:

Everyone was calling for water, but it was in vain. Death laughed at its harvest and Death stood guard on the barricade, so nobody could escape. Some raved about rescue, others for water. One comrade lay on the ground next to me and croaked with a breaking voice for someone to load his pistol for him.

The Germans managed to reclaim the Chemin des Dames one more time, before the final Allied push—engineered by General Philip Pétain—drove the Germans from the region.

By war’s end, the landscape was unrecognizable from what it was just a year earlier. Since the bodies in Winterberg tunnel weren’t French, no serious effort was made to recover them.

It wasn’t until 2009 that the Winterberg tunnel was once again put on the map. Since the mid-90s, Alain Malinowski, a worker on the Paris metro and avid history buff, had been combing the military archives in the Château de Vincennes for clues as to the whereabouts of the oft-forgotten tunnel.

That year, as a matter of chance, Malinowski came across a “contemporary map showing not just the tunnel but also a meeting of two paths that had survived till today,” writes the BBC. “With painstaking care, he measured out the angle and distance and arrived at the spot, now just an anonymous bit of woodland.”

“I felt it. I knew I was near. I knew the tunnel was there somewhere beneath my feet,” Alain Malinowski told the French newspaper Le Monde.

After alerting the proper authorities Malinowski was met with stony silence. A silence that would continue for the next decade until his son, Pierre, decided to force the hand of the French government by opening the entrance of the mass gravesite himself.

In January of last year, the 34-year-old former soldier led a team to the spot his father had identified some ten years earlier, and with a mechanical digger began the excavation.

After digging a little more than 12 feet, Pierre proved his father’s hunch to be correct.

Within the entrance of the tunnel Pierre and his team found the bell that was used to sound the alarm; hundreds of gas-mask canisters; rails for transporting munitions; two machine-guns; a rifle; bayonets; and the remains of two bodies.

The father-son duo once again contacted French authorities, but after ten months of continued silence, Pierre went public—telling his story to Le Monde.

The public’s reaction has been mixed, with some historians and archaeologists believing that the unsanctioned actions not only dishonor the dead but force the French government to now open and protect what lays buried there from looters.

The Winterberg tunnel is not the only mass gravesite that has been found in France. In 1973, more than 400 bodies of German soldiers were discovered in a tunnel at Mont Cornillet east of Reims, having died in a similar fashion.

Efforts to track down descendants were made throughout the 70s—an undertaking Pierre hopes to emulate with the men entomb in Winterberg.

So far, nine soldiers have been identified. Mark Beirnaert, a genealogist and Great War researcher, told the BBC, “If I can help just one family to trace an ancestor who died in the tunnel, it will have been worth it.”