Only one World War II U.S. Army Air Forces tail flash survives in the present-day U.S. Air Force: the Square D. Seventy-five years ago, on June 25, 1943, the 100th Bombardment Group (Heavy) first wore that emblem into battle.

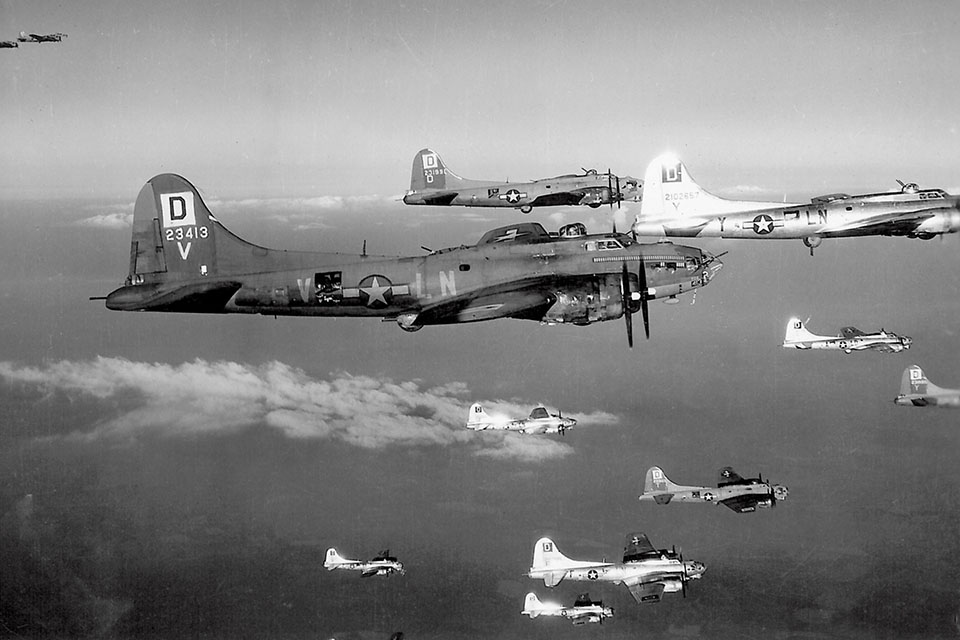

The 100th was constituted as a heavy bomber group inside the Eighth Air Force, which, at peak strength on D-Day, June 6, 1944, fielded 40 groups of Boeing B-17s and Consolidated B-24s. The 100th’s tail marking of a bold “D” on a square background was rendered on the vertical stabilizers of its B-17s, whose big, parabolic-shaped tail fins made for an effective if utilitarian canvas. In 2018 the Square D still adorns a Boeing aircraft—the KC-135R—though the 100th is now an aerial refueling wing. Even still, the Square D carries with it the heroic, bloody history of the 100th Bomb Group.

In November 1942, Colonel Darr Alkire was the first commander assigned to head up the 100th. By December, several hundred men formed the initial flying cadre of the group’s four bomb squadrons—the 349th, 350th, 351st and 418th—along with the requisite administrative, engineering and ground support units. While each unit was actively training, the Army Air Forces identified leaders who could forge the ungainly mass of civilians into airmen.

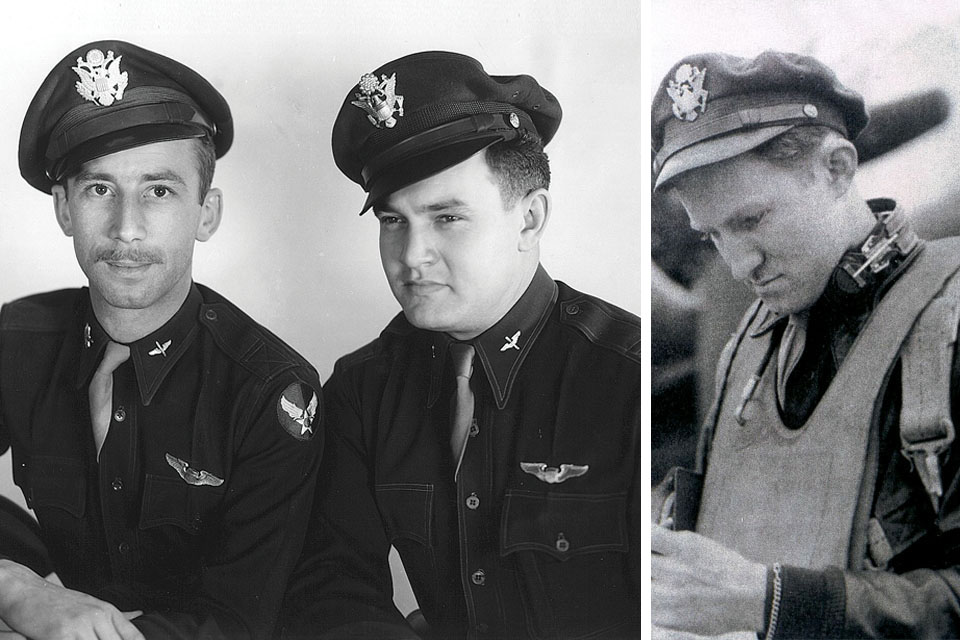

Among the commanders serving under Colonel Alkire were two officers who became synonymous with the unit’s early dashing, devil-may-care notoriety. John “Bucky” Egan was originally the 100th operations officer, and Gale “Bucky” Cleven was the initial commander of the 350th Bomb Squadron. Just two of the several Bucks or Buckys who would serve with the 100th, Egan and Cleven were excellent pilots and charismatic men. More than a few of the 100th’s young airmen came to view the two Buckys as inspirational figures, modeling their own behavior on that of these older leaders.

On the way to operational readiness, the group trained in Walla Walla, Wash., and, by the end of November, in Wendover, Utah. The third phase of training occurred in Sioux City, Iowa, where the crews focused on formation flying and navigation. In February 1943, the fliers were dispersed throughout the western United States and relegated to the role of instructors for new units. Ground personnel were assigned to the air base at Kearny, Neb. While in limbo, the group’s airmen regressed in their march toward combat readiness.

In April the lack of preparation and three months spent apart manifested in a training mission gone badly awry. Of 21 aircraft scheduled to make the 1,300-mile run between Kearney and Hamilton Field in California, three landed in Las Vegas (including Alkire’s ship) and one flew the opposite direction to Tennessee. The whole group, sans Alkire, who lost this command over the debacle (though he would later lead a B-24 unit), was sent back to Wendover for a much-needed refresher.

One of the more intriguing outcomes of continuing to keep the 100th Stateside for more training was the decision to replace all the group’s copilots with a recently graduated class of multiengine pilots from Moody Field in Valdosta, Ga. In a recent interview, a member of that class, John “Lucky” Luckadoo, said that breaking up crews who had worked for months to establish camaraderie and trust had a profoundly negative impact on morale. The 96-year-old Luckadoo called the decision “ludicrous” because it forced him and his classmates, who were sitting in the right seat of a B-17 for the first time, to undergo a difficult “learn-on-the-job” experience. Luckadoo recalled that he had accrued less than 20 hours of B-17 flight time prior to making the transatlantic crossing to Britain.

The 100th Bomb Group arrived in England in early June 1943, just one of the dozens of heavy bomber groups comprising the Eighth Air Force’s 1st, 2nd and 3rd air divisions. After a brief stay at an incomplete airbase in Podington, the 100th set up shop at Thorpe Abbotts airfield in East Anglia. The group’s airmen began flying over England and the Channel to get the lay of the land as they prepared for their first mission over enemy territory.

That first mission came on the morning of June 25, 1943, when 30 B-17s took off from Thorpe Abbotts for a raid on the submarine pens at Bremen, Germany. By the end of the day, the group had lost three Flying Fortresses and 30 crewmen, including pilot Oran Petrich and his crew, one of the first assigned to the 100th. The group acquired its reputation as a hard-luck unit very early in its operational history, and it would go on to become known as the “Bloody 100th,” a nickname laden with the weight of sacrifice.

On August 17, less than two months after its initial foray over enemy soil, the 100th flew to Regensburg for the first time. The raid was in the men’s self-interest, for it targeted a factory where Messerschmitt Me-109s—fighters that would torment them in the months to come—were assembled. It was a complex mission, requiring the coordination of two separate masses of Eighth Air Force bombers (the second was headed to Schweinfurt and its ball-bearing works) and Republic P-47 escorts. Ultimately it required the Regensburg-bound bombers to shuttle to North Africa, with a planned return to England at a later date. In the end, the 100th, located at the tail end of a 15-mile bomber stream, was left unescorted when one of the P-47 units never appeared.

As they approached Regensburg, “what seemed to be the whole German Air Force came up and began to riddle our whole task force,” wrote 418th Bomb Squadron navigator Harry H. Crosby in A Wing and a Prayer. “As other planes were hit, we had to fly through their debris. I instinctively ducked as we almost hit an escape hatch from a plane ahead. When a plane blew up, we saw their parts all over the sky. We smashed into some of the pieces. One plane hit a body which tumbled out of a plane ahead.”

Of the 24 American bombers lost that day over Regensburg, more than a third bore the 100th’s Square D on their tails. The 100th put up 220 fliers in 22 B-17s, and 90 of those men and nine Fortresses didn’t make the return trip to Thorpe Abbotts.

The group’s reputation as a hard-luck unit was sealed in the second week of October 1943, during missions to Bremen and Munster. On October 8, Lucky Luckadoo put his nickname to the test over Bremen. That day, he was flying in a combat formation position with the darkly humorous nickname of “Purple Heart corner,” the low plane in the low group.

Luckadoo noted that the Luftwaffe favored head-on attacks during those first months of combat flying by the 100th. The German fighters would “get out in front of our formation—in line abreast of 25 or 30 Focke-Wulfs or Messerschmitts—and spray the formation with cannon fire, rockets and .30-caliber machine guns.” As a result, he said, “We suffered tremendous fatalities.” Anti-aircraft artillery also took a toll, and Crosby noted that as they approached Bremen, the group encountered “Flak, a whole, mean sky full of it.” Luckadoo and his crewmates returned to Thorpe Abbots that day, but seven B-17s were lost and 72 aircrew died on the Bremen mission.

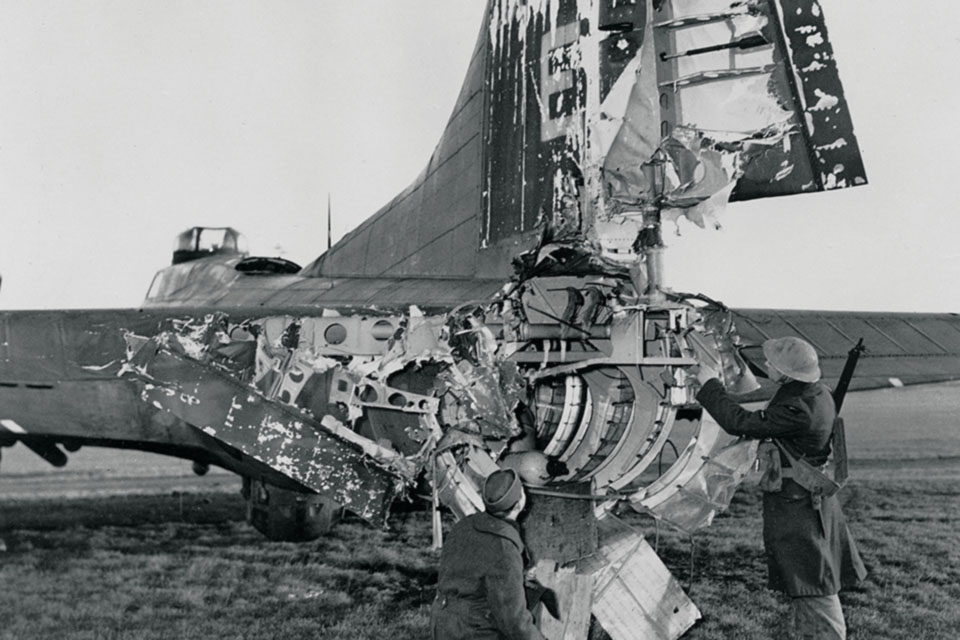

Crosby’s shot-up B-17 barely made it back on three engines to crash-land at an abandoned RAF airfield. After catching a ride in a lorry to Thorpe Abbotts, Crosby and his fellow crewmen, who were presumed lost, found their beds stripped and personal possessions removed. “On the bare cot were two clean sheets and two pillowcases, two blankets, one pillow, all neatly folded,” he wrote. “Ready for the next crew.”

Two days later, 21 Forts departed Thorpe Abbotts for Munster, but just 13 reached the target. The losses on the Munster mission were devastating: 12 aircraft and 121 men. A single B-17, Rosie’s Riveters, piloted by Lieutenant Robert Rosenthal, bombed the target and returned to Thorpe Abbotts that day.

The perceived impact of the losses was compounded by the attrition in squadron leadership: 350th Bomb Squadron commander Major Bucky Cleven was shot down over Bremen, and Major Bucky Egan, CO of the 418th Squadron, was downed over Munster on October 10 while trying to exact revenge for his best friend Cleven. The two commanders found themselves at the same POW camp. Legend has it that when Egan arrived, Cleven said, “What the hell took you so long?” The loss of the two Buckys, seen by the rank and file as exemplars of everything that a flier should be, was crushing.

Several days after these disastrous missions, the 100th was able to muster only eight aircraft for a raid that nearly broke the back of the Eighth Air Force. October 14, 1943, became known as “Black Thursday.” On that autumn day, 291 B-17s assembled to make a second raid on the ball-bearing factories at Schweinfurt. American losses were appalling: 60 aircraft shot down, 17 written off and more than 100 others damaged. The loss of more than a quarter of the aircraft participating in the raid was clearly unsustainable, both in the eyes of VIII Bomber Command and, perhaps more important, the American people.

In a twist of fate that served to highlight the randomness inherent in warfare, the 100th Bomb Group emerged comparatively unscathed that dreadful day. All eight B-17s that it contributed to the mission returned to Thorpe Abbots.

The October 1943 missions wound up being among the last bombing raids deep into German airspace that the Eighth Air Force flew without end-to-end fighter escort. Though the bombers bristled with .50-caliber machine guns (ultimately 13 in the B-17G, with its added chin turret to counter frontal attacks) and adhered rigorously to combat box formation flying to provide mutually supportive defensive fire, it was obvious that the B-17s in the European theater were vulnerable to Luftwaffe hunters. In the end, the primary tool for redressing the imbalance of power between the hunters and the hunted was to import a newer, more capable long-range fighter, the North American P-51 Mustang.

Though the fuel burn of aircraft is typically measured in gallons per hour, it’s also instructive to think in the traditional earthbound measure of miles per gallon. The P-51 was a pilot’s dream in terms of speed and maneuverability, but its real superiority was that it could eke out twice as many miles from a gallon of 100-octane avgas as could a P-47. With the Mustang, Army Air Forces planners finally had a fighter that could stay with the bomb groups all the way to Berlin and back.

Commander of the Luftwaffe Hermann Göring had once pompously bragged that Allied bombers would never be seen in the skies over Germany. By March 4, 1944, Allied bombers weren’t just flying over Germany, they flew all the way to Berlin. On that date, the 100th and their mates in the 95th Bomb Group became the first fliers to successfully bomb the German capital. For its efforts, the 100th was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation.

The ability to provide fighter escorts end-to-end on bombing missions had a profound effect on bomber losses suffered over Germany. The Eighth Air Force had lost nearly 30 percent of the bombers that took part in raids during the second week of October 1943. During what became known as the “Big Week” in February 1944, Eighth Air Force bombers suffered losses of only about 2 percent.

German flak and fighters weren’t the only dangers the heavy bomber crews faced. Flying in the foul English weather along the coast on instruments could be a formidable challenge. John Clark, a copilot in the 418th Bomb Squadron, flew the bulk of his combat missions in the depths of the wet and cold winter of 1944-45. He described instrument flying as “something you’re doing with the aircraft that was unique and important, to get this big device [bomber] through impenetrable fog or night…and bring it down to the ground.”

Danger wasn’t found only in the skies. Simply repairing and maintaining the massive B-17s could be hazardous to one’s health. At a recent gathering of 100th veterans, Master Sgt. Dewey Christopher, a crew chief in the 351st Bomb Squadron, recounted how a live magneto combined with the necessary act of hand-propping a Wright Cyclone R-1820 led to his being tossed 30 feet through the air by a suddenly active propeller as the engine tried to start. He landed on his head and then in the infirmary with a broken shoulder.

While the 100th lost only a single bomber on the first Berlin mission, the use of P-51s to provide air cover over Germany didn’t completely eliminate the group’s propensity for bad days. Two days later, on March 6, the 100th suffered its worst losses of the war—15 aircraft and 150 crewmen—on the second mission to Berlin.

The 100th Bomb Group flew its final combat mission on April 20, 1945, just days before the cessation of hostilities in Europe. As the war in Europe wound down, the 100th and numerous other Eighth Air Force bomber groups celebrated the weeks leading up to V-E Day on May 8 by exchanging their 500-pound general purpose bombs for containers of food, medical supplies, clothing, candy and cigarettes. The so-called “Chowhound” missions dropped thousands of tons of supplies to the long-suffering people of the Netherlands and France. So many 100th fliers wanted to be a part of the humanitarian efforts that the oxygen systems, unnecessary at low level, were removed from the B-17s, freeing up room for as many as four extra crewmen on each plane. The missions helped the 100th put a positive spin on what had been a harrowing experience.

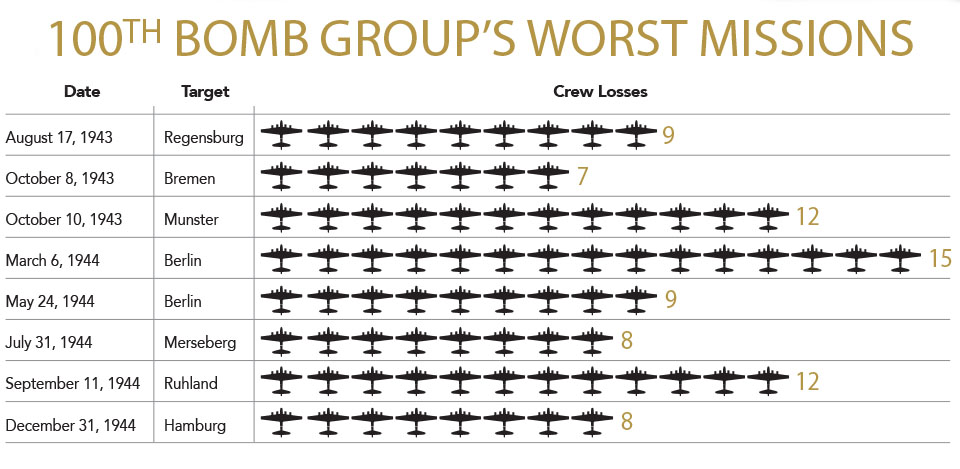

Over the course of 22 months of aerial combat, the aircrews of the 100th had served a deadly apprenticeship as they honed their skills and tactics. In an unemotional analysis of the raw numbers, the Bloody 100th’s wartime losses were not the worst suffered by the Eighth Air Force, though they were in the top three of losses by heavy bomber groups. The official history from the 100th Bomb Group Foundation cites 184 missing aircrew reports on 306 missions. In his memoir An Eighth Air Force Combat Diary, 100th copilot John Clark pointed out that “50% of the Group’s losses occurred in only 3% of its missions.” Like a gambler whose luck has gone cold, when the crews of the 100th had a bad day, they had a very bad day.

More than 26,000 Eighth Air Force personnel sacrificed their lives in service to the war effort. The total number killed or missing in action was slightly more than that suffered by the U.S. Marine Corps, and a little less than half the losses sustained by the entire U.S. Navy. Comparisons such as these do nothing to diminish the contributions of other military branches, but rather point out the gargantuan scale of the Eighth Air Force’s effort. The 100th Bomb Group’s portion of those losses was 785 men killed outright or missing in action and 229 aircraft destroyed or rendered unsuitable for flight.

In 2016 the Bureau of Veterans Affairs estimated there were 620,000 World War II veterans alive, but that we lose 372 per day. The responsibility for remembering, for commemorating the service of those veterans has fallen to their children and their grandchildren. In the case of the 100th Bomb Group, a number of organizations have taken up that obligation.

The 100th Bomb Group Foundation maintains an extraordinarily useful website (100thbg.com), and its members hold a biennial reunion. Last October, 17 group veterans, all in their 90s, attended the most recent reunion outside Washington, D.C. A smaller reunion takes place in February of each year in Palm Springs, Calif., in collaboration with the Palms Springs Aviation Museum. Other institutions connected with the 100th include the 100th Bomb Group Memorial Museum at the former Thorpe Abbots airfield; the American Air Museum at the Imperial War Museum in Duxford, England; the Museum of Air Battle Over the Ore Mountains in Kovarska, Czech Republic; and the National Museum of the Mighty Eighth Air Force near Savannah, Ga.

More than seven decades on, the actions of the men of the Bloody 100th still loom large in our cultural memory. Each time we refresh those memories, we ensure that their hard-earned lessons are not forgotten.

Douglas R. Dechow’s grand uncle Tech Sgt. Harry Dale Park was a member of the 100th Bomb Group. The 20-year-old Park was killed in a B-17 over Normandy on August 8, 1944. Dechow is the director of digital projects at the Center for American War Letters at Chapman University. Further reading: A Wing and a Prayer, by Harry H. Crosby; An Eighth Air Force Combat Diary, by John A. Clark; Century Bombers, by Richard Le Strange; and Masters of the Air, by Donald L. Miller.

this article first appeared in AVIATION HISTORY magazine

Facebook @AviationHistory | Twitter @AviationHistMag