It was the first clash between the U.S. Army and a Plains Indian tribe, and Colonel Henry Leavenworth judged it to be the very model of a modern military campaign. Between June 22 and August 29, 1823, his 6th Regiment of U.S. Infantry traveled nearly 640 miles up the Missouri River from Fort Atkinson at Council Bluff, in Missouri Territory (in present-day Nebraska), to the Arikara villages (in present-day South Dakota), engaged the enemy and returned to garrison. After their return, Leavenworth assembled his weary troopers and announced, “The blood of our countrymen has been honorably avenged, the Ricaras humbled, and in such a manner as will teach them, and other Indian tribes, to respect the American name and character.”

Nearly everyone who went up the river with Leavenworth disagreed. Joshua Pilcher, veteran fur trader and commander of Leavenworth’s erstwhile Sioux allies, wrote a letter to the colonel that concluded: “You came (to use your own language) to ‘open and make good this great road;’ instead of which you have, by the imbecility of your conduct and operations, created and left impassable barriers.” A campaign that began with decisiveness and promise ended as comic opera— comic opera that would dramatically affect the history of the American West.

If the end of the campaign had its comic elements, there was nothing funny about the event that set the U.S. Army in motion—the slaughter of more than a dozen trappers on a beach just below the Arikara villages on June 2, 1823. The story of how the trappers came to be on that beach began two years earlier.

In 1821 St. Louis was alive with the prospects offered by the fur trade on the upper Missouri. Two St. Louis businessmen, William Ashley and Andrew Henry, saw the possibilities. Ashley showed up in St. Louis in 1802. He was a risk taker and entrepreneur. Active in the militia and politics, he became lieutenant governor of the soon-to-be new state of Missouri in 1820 and brigadier general of militia in 1821. Henry had been Ashley’s partner in several mining ventures. In 1809 he had joined the pioneering Missouri Fur Company and led trapping brigades into the Rockies. Ashley needed that experience, so in 1821 he approached Henry and proposed that they team up again—this time to hunt for furs on the upper Missouri. Henry would command the fur brigades while Ashley looked to financing the venture, marketing the furs and supplying Henry in the field.

In March 1822, Ashley published a now famous advertisement: “The subscriber wishes to engage ONE HUNDRED MEN, to ascend the river Missouri to its source, there to be employed for one, two, or three years.” They signed up a crew of able-bodied men. Two of them, Jedediah Smith and James Bridger, stayed in the mountains long enough to change the course of American history.

Henry and his recruits set off in April 1822 for the mouth of the Yellowstone. Ashley followed with a shipment of sup plies and trade goods. He joined Henry on October 1 at Henry’s crude log fort but didn’t linger. He turned back, agreeing to return in the spring with another shipment.

In St. Louis in mid-November, Ashley put together the credit and supplies he needed for the next upriver run and once again began the hunt for qualified men. Early on he enlisted James Clyman, a man with uncommon intelligence and grit and a penchant for writing. Clyman read Shakespeare and Byron and wrote down his own experiences in a peculiar dialect that combined basic English grammar with wildly inventive spelling and punctuation. His first assignment was to sweep the city’s grog shops and whorehouses for likely volunteers. He signed up the unemployed and the homeless: “A discription of our crew I cannt give,” he recorded, “but Fallstafs Battallion was genteel in comparison.” Early in 1823, another ad was run in St. Louis newspapers—calling for 100 men “to ascend the Missouri to the Rocky Mountains, There to be employed as Hunters”—but his crew didn’t measure up to the one in 1822.

With credit, supplies and manpower, Ashley started upriver on March 10, 1823, with two keelboats, Yellow Stone Packet and Rocky Mountain. Henry meanwhile had been worrying about horses to mount the expeditions that Ashley’s supplies would support. The Crows refused to sell. Henry sent Smith downriver to intercept Ashley and warn him of the shortage. Ashley had no choice but to trade with the Arikaras, sometimes called the Rees, the only other source on the middle Missouri.

On May 30, he dropped anchor opposite two Arikara villages on the west bank of the Missouri just above the mouth of the Grand River in what would become South Dakota. Separated by a ravine, each of the villages contained about 70 earthen lodges. In 1805 Meriwether Lewis had estimated the total population at 2,600, which would have included about 500 warriors.

The Arikara warriors were sullen and unpredictable. They had lost two men in a recent fight with the Missouri Fur Company at Cedar Fort. Ashley made a careful approach. Clyman reported: “After one days talk they agreed to open trade on the sand bar in front of the village but the onley article of Trade they wantd was ammunition.” As a result, Clyman wrote, “we obtained twenty horses in three dys trading, but in doing this we gave them a fine supply of Powder and ball which on fourth day wee found out to [our] Sorrow.”

Ashley detailed Smith and a party of 40 men to bivouac on the beach and guard the horses. Several men went into the village in search of feminine comfort. Clyman who stayed with Smith on the beach recorded: “Our Interperter Mr [Edward] Rose about midnight he came runing into camp & informed us that one of our men [Aaron Stephens] was killed in the village and war was declared in earnest—Gnl Ashley our imployer Thought best to wait till morning and go into the village and demand the body of our comrade and his Murderer—We laid on our arms epecting an attact as their was a continual Hubbub in the village.”

At dawn Clyman’s expectations were fulfilled. The Arikaras opened fire. Smith’s men returned fire but couldn’t find clear targets. Clyman dryly observed after the fact, “You will easely prceive that we had little else to do than to Stand on a bear sand barr and be shot at, at long range

Their being seven or Eigh hundred guns in village and we having the day previously furnished them with abundance of Powder and Ball.” Horses screamed and reared, plunging wildly, trying to escape the balls, smoke, noise and terror that enveloped them. As dead and wounded animals fell to the ground, Smith’s men crawled up behind the bloody breastwork.

Ashley shouted for the boatmen to weigh anchor and rescue the besieged beach party. Two skiffs started for the shore. Arikara gunfire blasted the oarsmen as they crossed the open water. Pinned down by overwhelming fire, the men on the beach decided it was time to be gone. Seven, three of them wounded, swam to the skiffs. The others tried to swim to the keelboats. The Indians cut some of them down before they had made a good start. Wounded men disappeared beneath the water. Clyman escaped by swimming to the east bank and outrunning three Arikaras intent on taking his hair. Ashley gathered up those he could. One keelboat weighed anchor, and the crew of the other cut its cable. Both boats drifted downstream. The exchange had lasted 15 minutes. Including Aaron Stephens, cut to pieces in the Arikara village, 13 had died. Of the 11 wounded, two more would die. The casualties amounted to almost 30 percent of Ashley’s brigade—the highest in the history of the Western trade.

Not far downstream, Ashley stopped to regroup, planning to run upriver past the towns. Needing reinforcements, he dispatched Smith and a companion overland to summon Henry from the Yellowstone. Then, dropping farther downriver, he organized a new base on an island at the mouth of the Cheyenne River and took stock of his situation. He counted only 23 men likely to stick it out. Hard pressed to support even this small force, he sent Yellow Stone Packet downriver with 43 “deserters” and five wounded. The keelboat reached Fort Atkinson on June 18 and delivered a letter from Ashley describing the defeat on the beach. The attack outraged Leavenworth and the resident Indian agent, Benjamin O’Fallon. Pilcher, field com defeat on the beach. The attack outraged Leavenworth and the resident Indian agent, Benjamin O’Fallon. Pilcher, field commander of the Missouri Fur Company who had had run-ins with Arikaras, saw an opportunity to punish them and send a clear message to all the river tribes.

Two days after Yellow Stone’s arrival, Pilcher sent one of his men to Ashley with a message from O’Fallon. Leavenworth had decided to strike the Arikaras without waiting the weeks it would take to get permission from headquarters in St. Louis. He marched from Fort Atkinson on June 22 with six companies of the 6th U.S. Infantry, two 6-pounder cannons and some small swivel guns. Three keelboats transported supplies and part of the force. The rest proceeded by land. On June 27, carrying 60 men and a 51⁄2-inch howitzer on his two keelboats, Pilcher caught up with Leavenworth.

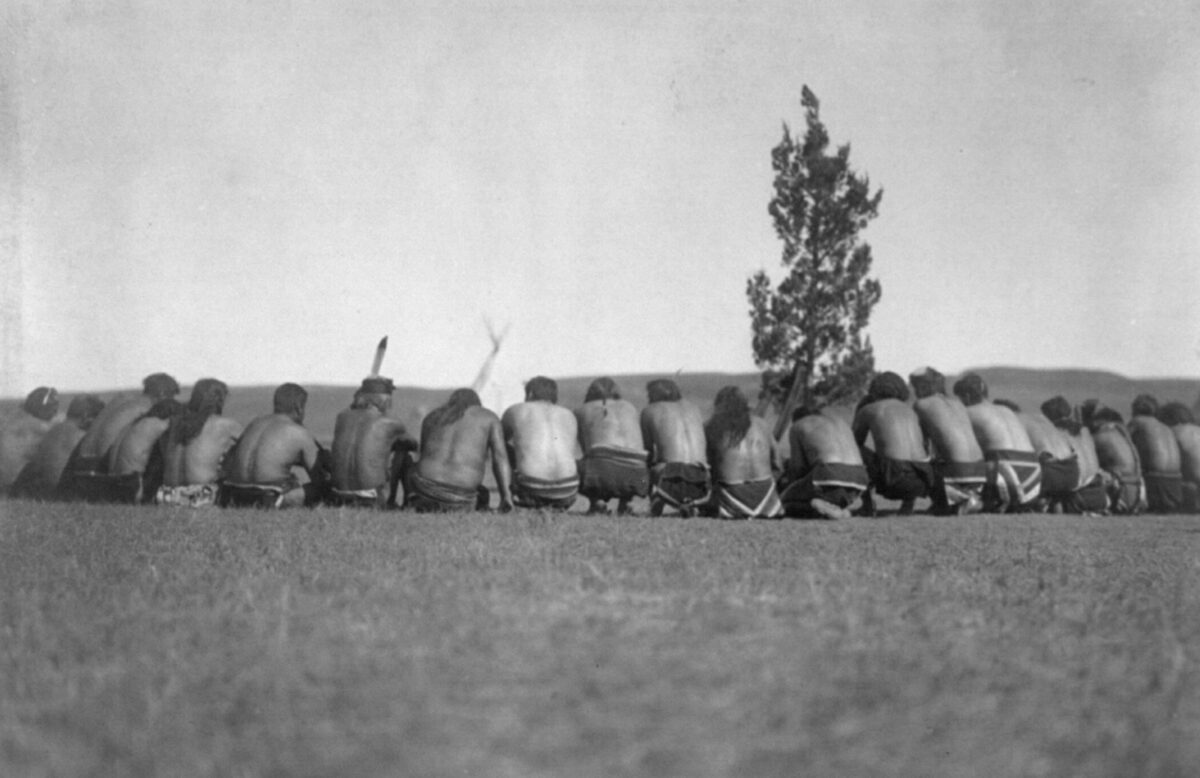

As Leavenworth headed north, Henry’s force moved south, joining Ashley at his camp at the beginning of July. Leavenworth reached them on July 30. There, he awaited Sioux reinforcements and made final adjustments to the structure of his “Missouri Legion.” The legion—230 infantrymen, more than 100 fur hunters and 750 mounted Sioux warriors—moved out to punish the Arikaras on August 2, 1823. A week later, the joint force crossed the Grand River five or six miles below the Arikara villages. Leavenworth ordered Pilcher and the Sioux forward to prevent the Arikaras from escaping. When the Sioux reached the plain in front of the villages, the Arikaras mounted and streamed out to meet them in a swirling melee. An hour later, the infantry, moving at the double quick, reached the scene. The Arikaras, seeing Leavenworth form his line of battle, broke off the fight and retreated to their villages. Phase one of Leavenworth’s battle plan had been successfully executed. Dale Morgan, Jedediah Smith’s biographer, described the result: “They had treed the coon. All that remained was for the artillery to come up and shoot the coon out of the tree.”

Early the next day, Leavenworth deployed his forces, determined that his artillery would destroy the Arikaras in their villages or drive them into the open, where his heavily armed infantry and mounted Sioux would cut them to pieces. He dispatched Captain Bennet Riley, with two companies of infantry and the Missouri Fur Company men supported by one of the 6- pounders, to the upper village. Just below the lower village, Ashley held the right flank against the river. A Lieutenant Morris, with the howitzer and the other 6-pounder, set up on Ashley’s left. Morris opened the attack. It continued all morning with little damage to the villages’ half-buried structures.

Watching the artillery rounds carom ineffectually through the villages, Leavenworth realized that these earthen lodges might have to be taken by infantry assault. He began an awkward, embarrassing dance of indecision. He had started up the Missouri on his own hook. What had seemed decisive and bold at Fort Atkinson now looked tentative. He was risking the lives of soldiers without headquarters’ blessing, and a direct assault might mean major casualties. He also risked provoking a prolonged and expensive Indian war in defense of a commercial expedition that was probably illegal. Ashley, after all, had a license to trade for furs, not to hunt them in Indian country, even though everyone understood that he meant to do just that.

Uncertain about the feasibility of taking the Arikara villages by storm, Leavenworth decided on a probing attack on the upper village. Captain Riley and a company of infantry would make the attack, supported by the other regular companies. Leavenworth assigned Ashley and his men to pin down the warriors in the lower village. Riley’s men swept into the upper village. Ashley’s force charged the lower village, occupying a ravine 20 yards from the stockade, blasting away at any hint of a target. Inside the upper village, the Arikaras sniped at Riley’s men from their mud huts, but the troopers met no concentrated resistance. Four companies of regular infantry, Pilcher’s hunters and the Sioux waited in reserve. Leavenworth lost his nerve. He ordered Riley to withdraw. Riley protested. Leavenworth repeated his order. Riley withdrew.

Pressed by his officers and the fur bosses, Leavenworth agreed to attack the lower village. The plan fizzled when he discovered that Lieutenant Morris had only 13 rounds of shot on hand and needed resupply. Leavenworth would not attack without covering fire, though he had just seen Riley and Ashley advance to the enemy stockade with only two wounded. He ordered his troops back to their original line. The Sioux went back to their camp. Leavenworth took a late lunch.

After lunch, the colonel discovered that some of the Sioux had stayed to parley with the Arikaras. Afraid of an alliance between them, Leavenworth, with Pilcher at his side, hurried to join the talks. An Arikara warrior intercepted Leavenworth to plead for peace. The colonel told him to bring out his chiefs to negotiate. When they appeared, Leavenworth demanded the return of Ashley’s property, five hostages and a pledge to remain peaceful. The chiefs agreed.

Pilcher and some of the officers watched in angry disbelief. When a pipe was passed to confirm the agreement, Pilcher refused to smoke and threatened brutal revenge on the Arikaras. Leavenworth ordered him to smoke. The trader took an angry puff, thrust the pipe away and renewed his threats. Not surprisingly, when Leavenworth picked his hostages, the frightened Indians refused to come. Shots were fired without doing damage, but negotiations were done for that day. Overnight, the Sioux, six Army mules and seven of Ashley’s horses disappeared.

The next morning negotiations resumed. Leavenworth directed Pilcher to draft a treaty incorporating the agreed-on terms. He refused. Henry also refused. Leavenworth drafted the four-article treaty himself. Article one required the Arikaras to return Ashley’s property. Article two stated that the Arikaras agreed not to molest the traders. Articles three and four contained promises of continuing peace between the United States and the Arikaras. Eleven Indians, whose authority Pilcher disputed, six Army officers and Ashley, who just wanted to get upriver, signed the agreement.

In response to the first article, the Arikaras delivered three rifles, a horse and 18 robes. Leavenworth’s officers and the fur men were enraged. The legion still had 120 rounds of solid shot and 25 rounds of grapeshot. Only two men had been wounded. They argued for an immediate, decisive assault. Leavenworth stalled, agreeing to attack the following day.

Rose meanwhile reported that the Indians planned to abandon their towns that night. Morning dawned eerily quiet. Despite Rose’s warning, no steps had been taken to prevent the Arikaras from escaping. They had vanished. Leavenworth sent Rose and others to find them and persuade them to return, but the mission failed. On August 15, the legion weighed anchor and started downstream. Looking upriver, Leavenworth saw the Arikara villages in flames. Although Pilcher denied any knowledge of the event, two of his men had torched the villages.

Reaching Grand River, the colonel disbanded his command. A fierce debate, played out in the national press, erupted over the conduct and outcome of the “Arikara War.” The Eastern establishment, having long ago murdered their red brothers, praised Leavenworth’s sympathetic treatment of the Arikaras. Western spokesmen characterized him as a vacillating imbecile who had done long-term damage to the commerce of the West.

Ashley took little part in the debate. He had other problems. He was $100,000 in debt. He had no idea exactly where the Arikaras had gone, but he could make a good guess at their mood and the mood of the Sioux who witnessed the pointless posturing of American might. He and Henry decided to abandon the river road and find a path overland to Crow country in what would become central Wyoming, a decision that would forever change the pattern of westward migration.

Two expeditions set out from Fort Kiowa (in what would become South Dakota). Henry led one, which was to sweep far to the west of the Arikaras to the Yellowstone, where he could mount fur expeditions south to the Big Horn basin and west to the Snake River. On September 30, 1823, Smith led the second due west through the Black Hills of South Dakota and into Big Horn country. By November, Smith’s party had reached the valley of the Wind River, where the men spent a dreary, frigid winter in the lodges of a Crow encampment. Early in February, they attempted to cross the Continental Divide into the valley of the Seedskeedee (Green) River, where they and the Crows would find countless beaver. Deep snow drove them back. The Crows told them of another, easier route around the south end of the Wind River Range. They fought through heavy snow and blizzard winds down the Popo Agie River and over to the Sweetwater. After weeks of struggle on the Sweetwater drainage, Smith crossed the Continental Divide.

In late spring, Smith’s trappers returned east over the route they had followed west. The pass that they crossed had been found and lost before. Robert Stuart’s party of American Fur Company men, headed east from Astoria, had gone that way in October 1812. This time it would be different. Smith’s South Pass became the preferred route for Ashley’s men to and from the fur grounds of the central Rockies. In 1830 the first wagons crossed the South Pass. Other parties followed them until the trail was permanently marked by the wagon wheels of half a continent’s worth of people bound for Oregon Country.

Andrew Henry needed horses. Aaron Stephens wanted an Arikara woman. Henry Leavenworth dithered. William Ashley persevered. Jedediah Smith crossed over to the Seedskeedee. That’s how the West was won.

Richard J. Stachurski, of Bellevue,Wash., enjoys writing about the mountain men and other Western subjects. Suggested for further reading: The Arikara War, by William R. Nester; A Life Wild and Perilous: Mountain Men and the Paths to the Pacific, by Robert M. Utley; and The American Fur Trade of the Far West, by Hiram M. Chittenden.

Originally published in the December 2006 issue of Wild West.