After a quiet, uneventful Christmas truce in 1967, I looked forward to the customary January truce for Vietnam’s Lunar New Year holiday, Tet, which would begin on Jan. 30, 1968. I was a 27-year-old newly promoted captain in the 262nd Quartermaster Battalion at Cam Ranh Bay and the duty officer on Jan. 30. The battalion commander, Lt. Col. Billy A. Spinks, was attending a unit or private function.

I drove my jeep to the headquarters of South Korea’s 9th Infantry Division, the “White Horse” Division, deployed around Cam Ranh Bay to protect the peninsula. I wanted to see if the Koreans planned to conduct any actions after the truce and needed our support for those operations.

Listening to an intelligence briefing that U.S. officials provided to the Korean division, I heard that a North Vietnamese underwater demolition team was in the area and targeting an oil tanker tied to the Cam Ranh Bay jetty.

Did I hear that startling intel right? Yes, I had. Had any similar warning been issued by the Cam Ranh Bay Support Command? No. Was there a time frame for such an attack? None was given.

To fully grasp the seriousness of that threat, it is important to understand the significance of Cam Ranh Bay to the war effort and the disaster that would occur if the communists blew up an oil tanker in the harbor.

The Cam Ranh peninsula juts southward into the South China Sea to the east and the sheltered bay on the west, forming the finest natural deep-water port in Southeast Asia. During the Vietnam War, the peninsula was spanned north to south by the 6th Convalescent Hospital, the Cam Ranh Bay Air Force Base, an ammunition storage area, steel storage tanks and the Cam Ranh Bay Support Command, which managed Cam Ranh depot and all logistics in the Central Highlands. The depot consisted of warehouses, outdoor storage areas, port operations and related units.

The storage tanks were filled with POL, the military’s abbreviation for petroleum, oil and lubricants—basically the fuels necessary to keep any modern war machine running.

Bulk and packaged POL was received, stored and distributed in Vietnam by three POL battalions: one near Saigon at Long Binh, another at Da Nang in the north, and the 262nd Quartermaster Battalion (POL), “the Lifeline to Victory,” in Cam Ranh Bay.

The 262nd Battalion comprised the Headquarters and Headquarters Company, the 524th Quartermaster Company (POL Operating), the 525th Quartermaster Company (POL Depot) and the 360th Transportation Company (POL truck). The 524th was responsible for removing bulk POL from commercial tanker ships tied up to the jetty and pumping the fuel through two 6-inch-diameter pipelines to the tank farm. The 525th operated a packaged-product warehouse, a drum yard, a POL staging area at the Cam Ranh Bay air base and five helicopter refueling facilities in the Central Highlands. The 360th operated three platoons of 5,000-gallon tanker trucks that hauled fuel throughout the area. The air base was supplied via a direct pipeline from the tank farm.

A key component of port security was the strong U.S. Navy presence established with the launch of Operation Market Time in 1965. The operation set up a surveillance force of naval vessels that would protect more than 1,000 miles of the South Vietnamese coast to stop enemy supply ships from slipping into the country. In Cam Ranh Bay, “patrol craft fast” vessels, commonly called swift boats, were always on patrol in the port and around ships at anchor in the outer harbor.

Market Time forces had never before been challenged in the bay. Nor did the Korean White Horse Division ever have to contend with a ground attack directed at Cam Ranh Bay. Troops stationed there were considered so safe that weapons and ammo were kept in unit arms rooms. Few perimeter bunkers were manned as there was little reason to fear a ground attack or indirect fire from shore, sea or air.

I was assigned to the 262nd Quartermaster Battalion in November 1967 after graduating from the officer’s POL course at Fort Lee, Virginia. At Cam Ranh Bay, I served as the battalion’s intelligence officer and was detailed to work with the operations officer. Aside from maintaining control of a few classified documents, no vital security functions required my attention.

A few times weekly, I took my jeep across the pontoon bridge to the mainland and attended the U.S. briefings given to the White Horse Division staff. I wanted to see if the Koreans planned to conduct operations in the area, which meant we would need to provide POL supplies for the involved units.

After the Jan. 30 briefing where I learned about the NVA underwater demolition team, I drove back to my battalion as fast as possible. After negotiating the one-way-at-a-time bridge and waiting 30 minutes to get back across, I made a beeline for battalion headquarters and arrived about 3 p.m., finding it even sleepier than when I left.

I observed a tanker—the Pelikan, a Shell Oil Co. ship—on the jetty pumping a type of jet fuel designated JP-4. There was always a high demand for that product, and it had been awhile since a tanker with JP-4 docked.

I made several attempts to contact my battalion commander, executive officer and operations officer to relay the unsettling intelligence I had heard. Despite making continuous radio calls and sending runners, I was unable to contact any higher-ups. I was the only officer on duty at headquarters and totally out of contact with my superiors.

Although some details of the intel report were clear, the planned time for the attack was still a mystery. It would probably occur at the end of the truce, but what if it happened sooner? I wondered if it could happen that night. I scanned our operating procedures twice but found no guidance—not even the procedure for moving a ship.

I knew it took about two hours to stop pumping fuel and get a ship off the jetty. If I was going to move the Pelikan, I needed to proceed immediately since it was getting late in the afternoon. Without hesitation, I assumed sole responsibility and issued the order to move the Pelikan to the outer harbor.

That order prompted many actions. The tanker had to stop pumping. Fuel lines had to be shut down and disconnected. Rope handlers and tugboats needed to be ordered. The ship’s captain had to be briefed. Coordination with the harbormaster’s office was required. More guards needed to be put on the ship, and that required an increase in the number of drop lights so the guards could see in the water. We also had to get radios and frequencies to contact Market Time.

I was understandably scared—not so much of the enemy but of the battalion commander, who would be furious. I had never done anything like this before, nor moved a ship from the jetty. I knew I would be labeled an alarmist, but I did what I thought had to be done.

When the commander of the 524th Quartermaster Company got word that I had ordered more guards to be placed on the ship, he did not want to comply and said he would call the battalion commander. I replied: “Please do! I’ve been trying to reach him.” He was a more senior captain.

When he, too, was unable to locate battalion commander Spinks, he rounded up his troops and posted them on the ship. I went to the port to brief the Pelikan’s captain, saw the troops board and ensured the operation was going well.

I returned to battalion headquarters and found myself in deep trouble. Spinks had observed the Pelikan being pushed away from the jetty by the tugboats. He contacted me on the radio and demanded to know what was happening. I offered to go to his location and explain my decision, since it could not be said over the radio. Spinks ordered me to stay at the headquarters. He was on his way.

I expected a turbulent meeting, but there was nothing I could do. Spinks’ jeep roared up to the building. He hopped out wearing civilian clothes, rushed in and demanded: “What is going on?” I told him of the threat and what I had done to move the Pelikan. He was furious. I had apparently done the wrong thing. I explained that we had been constantly trying to reach him, but that thin excuse got me nowhere.

“Capt. Bryan, don’t you know Cam Ranh Bay has never been attacked?”

“Yes, sir,” I replied.

“Capt. Bryan, are you not aware we are in a period of truce?”

“Yes, sir, I am.”

“Capt. Bryan, don’t you know we are critically short of JP-4?”

“Yes, sir, I do.”

“And you still moved the ship?”

“Yes, sir, I did.”

“Capt. Bryan, don’t you ever move another ship again.”

Spinks turned to the noncommissioned officers on duty and asked if the Pelikan could be brought back to the jetty immediately. They told him no. Night movements of ships were prohibited for safety reasons.

Becoming even angrier, Spinks turned to me and ordered me into his office. He followed me in and slammed the door shut. He repeated his questions and accused me of hurting the war effort. He said he did not want one of his officers to take such actions on their own. After a long period of shouting, he relieved me of my duties, sent me to my quarters and told me I would be sent back to the States the next morning.

I knew my Army career was over. Although I might not have been immediately released from active duty, the efficiency report Spinks was likely to render would have ended any prospects for advancement. The Army did not need officers who cannot perform under combat conditions and therefore I was certainly of no use to the military, he had told me.

My mind raced as I headed to my quarters. The commander was correct in all that he said. I knew those issues and had weighed them when I decided to move the Pelikan.

I had never known an officer relieved of his duties “for cause.” Now I was one. How would I face my family and friends? What would I do with my life?

I drifted off to sleep and woke at my usual early hour. I grabbed a towel and my flip-flops and went to the communal shower, a frame, tent-covered structure with showerheads in the ceiling. There were three other men who had just come off the night shift, probably from the Support Command headquarters. I overhead one of them remark that a ship got hit during

the night.

It was now Jan. 31. I sat on my cot, unsure of what was in store. Would Spinks charge me under the Uniform Code of Military Justice for taking unauthorized and unprecedented action? I thought it a real possibility. What could the charge be? Would there be a court-martial?

However, by noon, no one had come to get me. As I walked 3 or 4 miles to the battalion headquarters, I noted more activity on the roads than normal.

This was strange given the truce. By the time I got to the battalion office, I was dripping with sweat. I really did not want to face the commander, the executive officer or the operations staff.

To my surprise, the operations section was a beehive of activity. Men were on phones and radios, shouting orders, asking for inventory figures, ordering aircraft so we could fly POL supplies and having meals brought to the office. This was everything one would expect in a crisis. I saw the Pelikan had returned to the jetty and another tanker was moored alongside it.

I quickly learned that all hell had broken loose over Vietnam in the pre-dawn hours of Jan. 31, as the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong launched the main thrust of their Tet Offensive (premature attacks had occurred on Jan. 30).

There was heavy fighting everywhere in the country. The U.S. Embassy had been attacked and was reported to be in the control of enemy forces. The VC and NVA had thrown everything they had into the assaults, and we were initially taking a beating.

The other two POL battalions, in Saigon and Da Nang, were unable to issue fuel, leaving our battalion as the only source of POL in Vietnam. No one told me to go to work. I just joined the action. I saw commander Spinks in his office.

During the many times he came out giving orders or seeking data, he did not speak to me. But he did not kick me out of the building, either—he was too busy with other matters. We were experiencing the highest-ever demand for JP-4, and I had sent away the very ship that was resupplying the vital fuel for U.S. aircraft. Yet that had turned out to be a good thing.

At midnight, six NVA frogmen had swum to the jetty to destroy the Pelikan with explosives. They knew it was moored and pumping JP-4. They also knew that the tide was outgoing, which would spread the burning fuel throughout the port facilities. The flames from the Pelikan could have reached piers with as many as eight ships tied up discharging cargo.

Even if the fire did not destroy the other ships, the flames and detonations would have caused a tremendous loss of lives and ruined the docks and materials-handling equipment operating there—a near total destruction of the port.

However, when the frogmen arrived at the jetty to carry out their sinister work, they noticed something was missing. The Pelikan had disappeared.

The frogmen turned and started back across the bay. They had been specifically ordered to blow up and sink the Pelikan and didn’t have the freedom to select another target. When the would-be saboteurs got halfway across, swimming amid the night lights on the ships at anchor waiting to be unloaded, they spotted the Pelikan. Their revelation was aided by the extra drop lights I had ordered so our troops could see anyone approaching the waterline.

Like moths to a flame, the frogmen swam the 7 or 8 miles to their target. When they got to the Pelikan, the swimmers discovered they had lost the devices to fasten six bombs onto the side of the ship. Exhausted and facing a wall of steel, they gathered around the anchor chain and began tying the bombs to it.

The guards heard them and opened fire. Within minutes, swift boats swarmed the Pelikan and dropped depth charges in the water. Five frogmen were killed. One was captured. The prisoner provided the information about their failed attack.

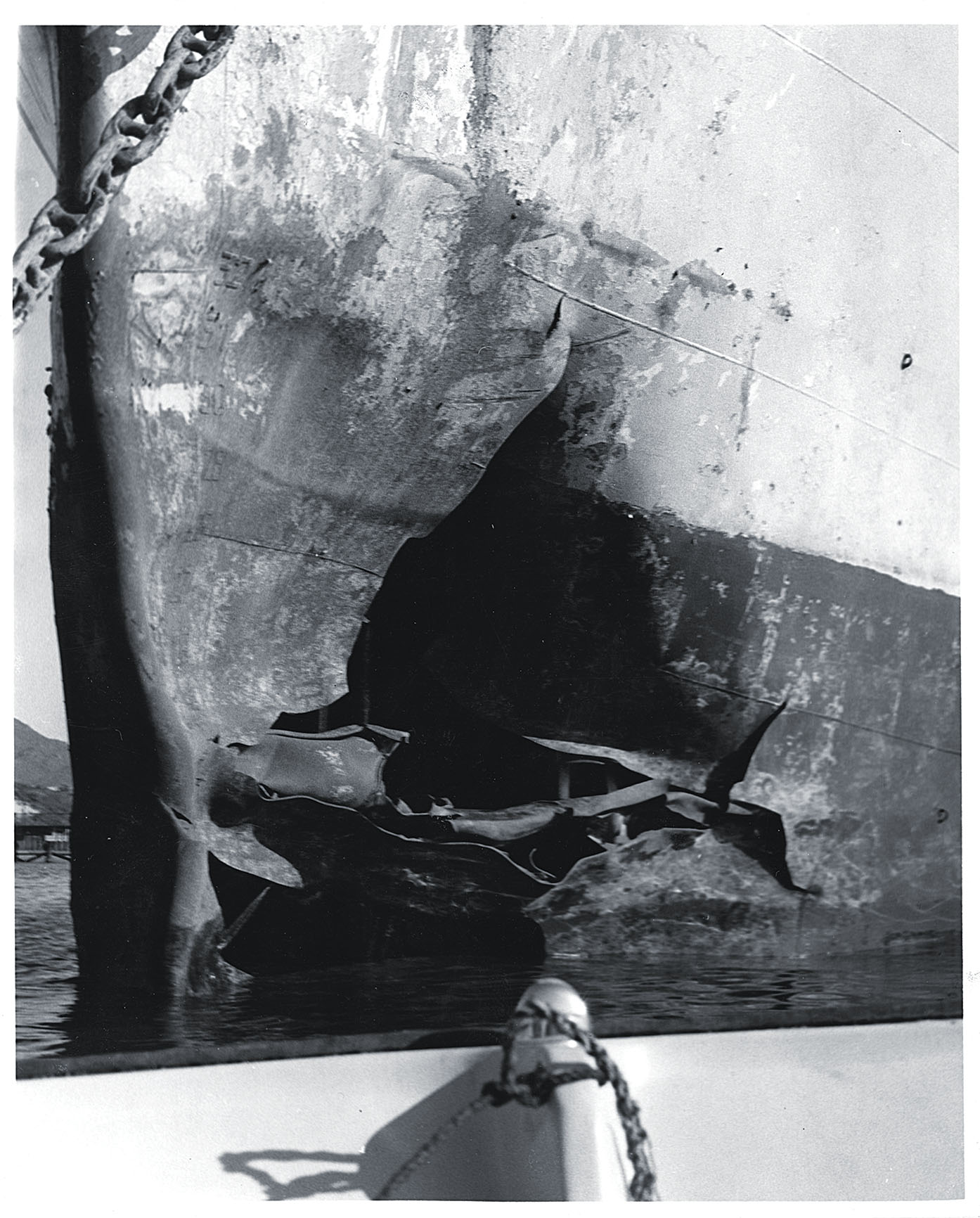

Meanwhile, the NVA’s active bombs remained tied to the anchor chain. The Navy summoned the explosive ordnance detachment, but the bombs went off before the unit arrived.

Exploding about 6 feet underwater, the bombs blew a hole in the bow of the ship where paint was stored but completely missed the JP-4 fuel. If the captain of the Pelikan had simply let out more anchor cable, the bombs would have been moved even farther away from the ship and have caused less or no damage.

At daybreak, the ship returned to port and resumed offloading. To speed up the process and get the Pelikan’s damaged section above water, a second ship was moored alongside and took the JP-4 into its tanks. The Pelikan’s captain and crew were anxious to unload and leave.

Even though the 262nd Quartermaster Battalion was now sending fuel by aircraft all over Vietnam, the crisis did not subside until the other POL battalions resumed operations and the most intense fighting ended in March. Communist forces made some early spectacular gains, but they were temporary and came with tremendous losses. We encountered losses, too, but in the end the Tet Offensive was a huge military defeat for the enemy.

The NVA came close to knocking all three POL battalions out of service on the first day of their offensive. Had the attack on Cam Ranh Bay been successful—if the Pelikan had been on the jetty—the resulting explosions and fire would have been a greater public relations victory for the enemy than penetrating the embassy grounds.

The Cam Ranh port escaped destruction because a junior captain acted on the intelligence he heard and took the right action. The battalion commander never mentioned anything to me again about moving the Pelikan, nor did he fulfill his threat to end my career.

On the other hand, I received no recognition, nor was there any complimentary mention of my action in my efficiency report. If anyone at the Support Command asked why the Pelikan was moved, I never heard of it. None of the soldiers placed on the ship were recognized for their actions either.

Not knowing all official procedures, I had moved the Pelikan without any authority to do so. I did not know that only the Cam Ranh Bay Support Command could order a ship to be moved. That explained why I could find nothing in the battalion procedures manual about moving a tanker—we had never moved one! V

Two months after the attack, Lt. Col. Billy A. Spinks appointed Hardy W. Bryan to command the 525th Quartermaster POL Depot Company. He retired from the Army as a lieutenant colonel and resides in St. Petersburg, Florida.

This article appeared in the February 2021 issue of Vietnam magazine. For more stories from Vietnam magazine, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: