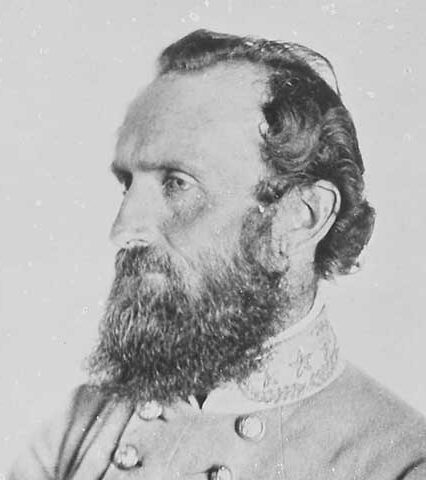

Even as Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson supervised the movement of his Second Corps from the Shenandoah Valley toward Fredericksburg, Va., in late November 1862, his mind was far away, in Charlotte, N.C., where his wife, Mary Anna, was due to give birth any day. Although he did his best to keep his emotions hidden, the famously reserved Confederate commander was particularly anxious because he and Mary Anna had lost one child already—a daughter, Mary Graham, who died of jaundice in May 1858 after only three weeks. Adding to his angst, his first wife, Ellie Junkin, had died during childbirth back in 1854, along with their stillborn son. Jackson had asked Mary Anna not to telegraph him news about the birth, telling her, “It is a joy with which no stranger should intermeddle.” While the devout general waited for a letter bearing good news, he prayed fervently for the well-being of his wife and unborn child.

About November 28, with Jackson’s Corps somewhere between Gordonsville and Orange, news finally arrived. His sister-in-law, Harriet Irwin, informed him that Mary Anna had given birth to a daughter, and that both mother and baby were well. A longer letter arrived shortly thereafter, again written by Harriet. The letter’s salutation, however, suggested a different author:

My own dear Father,

As my mother’s letter has been cut short by my arrival, I think it but justice that I should continue it. I know you are rejoiced to hear of my coming, and I hope that God has sent me to radiate your pathway through life. I am a very tiny little thing. I weight only eight and a half pounds, and Aunt Harriet says I am the express image of my darling papa…and this greatly delights my mother. My aunts both say I am a little beauty. My hair is dark and long, my eyes are blue, my nose straight just like paper’s and my complexion not all red like most young ladies of my age, but a beautiful blending of the lily and the rose.

According to the letter, Mary Anna had come through the delivery well, and was resting comfortably. But, Jackson would be informed, “She is anxious to have my name decided upon, and hopes you will write and give me a name, with your blessing.”

Jackson had originally hoped for a son, because, as Mary Anna later explained, he believed “men had a larger sphere of usefulness than women.” But, according to Mary Anna, he abruptly changed his mind: “[H]e said he preferred having a daughter, since God had ordained it.” Jackson left no doubt in a letter to mother and daughter, writing that “he loves her better than all the baby-boys in the world, and more than all the other babies in the world.”

He named his daughter Julia, in honor of his mother. “My mother was attentive to me when I was a helpless, fatherless child,” he told Mary Anna, “and I wish to commemorate her now.”

Jackson’s youth had been wrought with family tragedy. In 1826, when Jackson was two years old, he lost both his father and his older sister Elizabeth to typhoid fever, and in 1841 his older brother Warren died of tuberculosis. In 1830, Jackson’s mother remarried, but she would die a year later, two months after giving birth to a son, William Wirt Woodson. Jackson and his half-brother would eventually become estranged.

At the time of his mother’s death, Jackson and his little sister, Laura—two years his junior—were being cared for by their father’s brothers in Weston, Va. (modern-day West Virginia). That environment, however, was not appropriate for a young lady, so Laura was soon sent to live with family in Parkersburg. Jackson’s strong bond with his beloved younger sister would gradually diminish, and when the Civil War began, Laura—a staunch Unionist—stopped talking to her brother altogether when he sided with the Confederacy. Jackson nevertheless gave his new daughter the middle name “Laura” in honor of his sister. (Later in life, Julia would change her own middle name to “Thomas” in honor of her father.)

Jackson had originally hoped for a son.

Because of repeated losses in Jackson’s family during his life, it is perhaps little wonder he wanted a family of his own probably more than anything else. Surely, word of Julia’s healthy birth was the sort of news for which he had long prayed. Mary Anna later noted that her husband received it “as if his heart trembled at the very thought of so much happiness.”

And yet he shared the news with no one. “[H]e kept the glad tidings to himself,” Mary Anna recalled, “leaving his staff and those around him in camp to hear of it through others.” A month passed before they even knew, in fact. To share the joy, Jackson feared, would be to risk calamity. Although a devout Presbyterian, he was at heart a good old-fashioned Calvinist who believed in a jealous and angry God. Jackson believed he had lost his first wife and child, as well as his and Mary Anna’s first daughter, because he had loved them too much and that God had responded by taking them away in piques of jealousy. “We are sometimes suffered to be in a state of perplexity, that our faith may be tried and grow strong,” he once said, trying to make sense of the tragedy in his life and come to grips with his grief.

In the spring of 1857, Mary Anna’s sister, Isabella, and brother-in-law, future Confederate General Daniel Harvey Hill, lost a son. Jackson revealed he was “not surprised” the child had been “taken away” by God. “I have long regarded [D.H. Hill’s] attachment to him as too strong,” he confided in a letter to Mary Anna; “that is, so strong that he would be unwilling to give him up, though God should call for his own.”

Jackson was quick to caution Mary Anna about their own child: “Do not set your affections upon her, except as a gift of God. If she absorbs too much of our hearts, God may remove her from us.” Keenly aware that things in Charlotte could have gone far differently, Jackson did not want to risk upsetting the outcome. “I fear I am not grateful enough for unnumbered blessings,” he worried in a subsequent letter.

As 1862 stretched into 1863 and winter deepened, Jackson’s responsibilities kept him at the front. “[I]t is important that I, and those at headquarters, should set an example of remaining at the post of duty,” he explained. Yet he longed to see Mary Anna and especially Julia. “I haven’t seen my wife since last March, and, never having seen my child, you can imagine with what interest I look to North Carolina,” he wrote. In another letter he expressed how much he would “love to see the little darling, whom I love so tenderly, though I have never seen her; and if the war were only over, I tell you, I would hurry down to North Carolina to see my wife and baby.” He playfully suggested on another occasion that, since he couldn’t make it south, maybe Julia could come to him. “Can’t you send her by express?” he asked in good humor. “There is an express line all the way to Guiney’s [Guinea Station].”

Despite the separation, his frequent letters reflected attempts to parent from afar. “I am grateful at hearing that you have commenced disciplining the baby,” he told Mary Anna. “Now be careful and don’t let her conquer you. She must not be permitted to have that will of her own.”

Nevertheless, he could not keep himself from doting any more than Mary Anna could—though it continually weighed on his mind. “I am sometimes afraid that you will make such an idol of that baby that God will take her from us,” he would confide to her. “Are you not afraid of it?”

In March, they suffered a near-miss. Julia, only four months old, contracted a severe case of chicken pox. Jackson enlisted advice from his own doctor, Hunter Holmes McGuire, which he sent to Mary Anna by letter. “I do wish that dear child, if it is God’s will, to be spared to use,” Jackson added.

About this time, Jackson experienced another tragic reminder of the precariousness of young life. During the winter he had grown close to the Corbin family, on whose estate, Moss Neck, he encamped. In particular, the family’s 6-year-old daughter, Janie, took a shine to the general, and she often appeared in his office for play dates. They would frolic on the floor or she would cut out paper dolls, which she called her “Stonewall Brigade.” Jackson, in turn, kept treats in his desk for her. “She was the General’s delight,” a staff officer noted. However, on March 17, just a day after Jackson relocated his headquarters, word arrived that Janie and two of her cousins had died of scarlet fever. Jackson wept openly at the news, then threw himself into fervent prayer. Their early deaths weighed on his mind as he thought of his own daughter hundreds of miles away.

Jackson finally had the opportunity to unite with his family on April 20, 1863. Mary Anna and Julia traveled by train from Charlotte to Richmond, then north to the Confederate railhead at Guinea Station, a dozen miles south of Fredericksburg. Awaiting their arrival, Jackson stood on the train platform in a heavy rain, wrapped in his India rubber raincoat. When the locomotive chugged to a stop, he stepped aboard to meet his daughter for the first time. “[H]is rubber overcoat was dripping from the rain which was falling, but his face was all sunshine and gladness,” Mary Anna recalled; “and after greeting his wife, it was a picture, indeed, to see his look of perfect delight and admiration as his eyes fell upon that baby!”

“I never saw him look so well,” she continued. “He seemed to be in excellent health & looked handsomer than I had ever seen him, & and then he was so full of happiness at having us with him & seeing & caressing his sweet babe, that I thought we had never been so blest & happy in our lives.”

Mary Anna offered to let her husband hold the baby, but “[h]e was afraid to take her in his arms, with his wet overcoat.” Instead, as they stepped off the train together, Jackson held an umbrella over his wife and child as they walked to his waiting carriage, his eyes fixed the entire time on his tiny daughter. Around them, Confederate soldiers at the depot “cheered them loudly when they saw her and him together,” one of Jackson’s staff members recalled.

The next nine days were the happiest of Jackson’s life. He, Mary Anna, and Julia finally had the opportunity to be a family. “To a man of his domesticity and love for children this was a crowning happiness,” Mary Anna said.

While official duties kept Jackson busy, he devoted as much time as he could to his wife and daughter, “little Julia sharing his chief attention and care.” People remarked on Jackson’s devotion to her—a “happy pair together.” They even performed Julia’s baptism, with General Robert E. Lee among the attendees.

The family’s visit, according to staff officer Henry Kyd Douglas, “begat more or less social gayety and everybody called on Mrs. Jackson and little Miss Stonewall. Troops would be brought near for parade and review, and the baby would be carried to where they could get a view of her.”

Despite his often-reserved public persona, Jackson usually was playful with children—such as Janie Corbin—during the war. He didn’t, however, seem to know quite how to handle a child of only five months. “The General took her in his arms and began playing with her—which I confess he did rather awkwardly and as if quite unused to the occupation,” recounted an amused Raleigh Colston, one of Jackson’s division commanders, after calling on the family one afternoon.

Jackson had wanted nothing more in life than to be a father[/quote] When Julia cried to be lifted from her crib, Jackson tried to break her of the habit by leaving her there until she stopped. “So there she lay, kicking and screaming, while he stood over her with as much coolness and determination as if her were directing a battle,” Mary Anna recalled; “and he was true to the name of Stonewall, even in disciplining a baby!” When Julia stopped crying, Jackson held her, and if she began to cry again, he would lay her back down. “[T]his he kept us,” Mary Anna later said, “until finally she was completely conquered, and became perfectly quiet in his hands.”

All in all, Henry Kyd Douglas would attest, “the General was the model of a quiet, well-behaved first father.”

On April 29, the Union Army of the Potomac rumbled to life near Chancellorsville, Va., and word arrived at Jackson’s headquarters that he was needed to help plan the Confederate response. With “a tender and hasty good-by,” he bundled his family onto a train to Richmond, where Mary Anna stayed with friends as they awaited news from the front. By the evening of May 3, however, it was rumor rather than news that arrived: Something terrible had happened to her husband on the battlefield.

On the evening of May 5, Mary Anna’s brother, Thomas Morrison, who served as an aide on Jackson’s staff, arrived disheveled at the door. After a harrowing trip south, he had come to collect his sister and escort her north. Her husband had lost an arm during the battle, and while the initial prognosis suggested a favorable recovery, Morrison indicated that she was needed by her husband’s sickbed.

Once more, Mary Anna and Julia boarded the northbound train to Guinea Station. At the Confederate railhead, she found her husband convalescing at an adjacent plantation, awaiting transport back to the hospitals in the capital. His condition had deteriorated, however, making him too weak to travel—though he did seem to rally at his family’s arrival. “The general’s joy at the presence of his wife and child was very great, and for him, unusually demonstrative,” McGuire noted.

Mary Anna stayed by Jackson’s side, leaving only to nurse Julia, who was otherwise tended by Mary Anna’s servant, Hetty, and family friend Susan Hoge. “Thinking it would cheer him more than anything else to see the baby in whom he had so delighted, I proposed several times to bring her to his bedside,” Mary Anna said—but her husband demurred. He did not want the baby to see her father in such a state. “Not yet,” he said. “Wait till I feel better.”

But by the morning of Sunday, May 10, doctors had become convinced that Jackson would not survive the day. At last, he relented and allowed Mary Anna to bring the baby to him. “[A]lthough he had almost ceased to notice anything,” she recalled, “as soon as they entered the door he looked up, his countenance brightened with delight, and he never smiled more sweetly as he exclaimed, ‘Little darling! Sweet one!’”

Mary Anna placed Julia on the bedside next to her dying father, noting that Jackson watched her “with radiant smiles” for a few moments. McGuire later remarked on how Jackson played with the baby, “frequently caressing it, and calling it ‘my little comforter.’” Finally Jackson raised his wounded right hand—which also was struck during the friendly fire incident that had cost him his left arm eight days earlier—over Julia’s head. With closed eyes, he “was for some moments, silently engaged in prayer.”

Thomas Jonathan Jackson had wanted to be a father for most of his life, and unfortunately had had a chance to see his daughter only twice—once for a nine-day stretch in late April when she was five months old and once on his deathbed, just hours before he passed away. Shortly after seeing his daughter that final time, he slipped into delirium for good. After shouting out disjointed battle commands (“Order A.P. Hill to prepare for action! Pass the infantry to the front rapidly! Tell Major Hawks…”), Jackson relaxed and offered in a calm voice, “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees.” With that, the 39-year-old general died. Julia outlived her father by only 25 years. After a childhood as the “Orphan of the Confederacy”—the daughter of a martyred hero—she had the opportunity as a young bride to move to California with her new husband, William Edmund Christian. Eventually growing homesick, she wrote to her mother for permission to return. But the day she stepped off the train in Richmond—August 28, 1889—a typhoid epidemic was sweeping through the capital. Julia contracted the disease and died within two days, a few months short of her 27th birthday.

Julia left behind a daughter and a son, Julia Jackson Christian and Thomas Jonathan Jackson Christian, whom Mary Anna raised. As the “Widow of the Confederacy,” Mrs. Jackson lived until 1915.

Mary Anna and Julia are both buried with Thomas Jonathan in Stonewall Jackson Cemetery in Lexington, Va., their adopted hometown. They now rest together in a memorial plot at the foot of a granite obelisk topped by a bronze statue of Jackson—reunited as a family once more.

Chris Mackowski is a writing professor at St. Bonaventure University and editor-in-chief of the blog emergingcivilwar.com. He is the author of a number of books on the Civil War, including The Last Days of Stonewall Jackson: The Mortal Wounding of the Confederacy’s Greatest Icon, co-authored with Kristopher D. White.