Scott Halverson and Margaret Moore, partners in Minneapolis-based Northern Stone Carving LLC, have overcome challenges in restoring damaged monuments at Gettysburg National Military Park and elsewhere. Among their projects have been 38 repairs to 14 monuments at Gettysburg National Military Park and the 21st Indiana Battery monument in Chickamauga, Ga. The two met while working on stone carving in the restoration of the State Capitol in St. Paul, Minn., in 2014 and founded their company in 2018.

CWT: How did you become stone carvers?

SH: I have been carving stone for 20 years. I was an art major in the ’80s and got interested in working with stone while traveling in Europe. When I got back, I found a place to start learning in Austin, Texas, and later went back to Minnesota, where I found an apprenticeship with a French stone carver. After working with him for a few years, I started working for myself.

MM: I had a different path. I was introduced to stone carving in South Carolina, at the American College of the Building Arts in Charleston. I was interested in art, and this path was a good fit. I received a Bachelors of Science in architectural stone carving at the only degree-seeking and accredited craft college in the nation. I have spent time in England and had the privilege of working with the Lincoln Cathedral Works Department as well as a summer with The Prince’s Foundation.

CWT: How do you begin to restore a Civil War monument?

MM: You need to understand the artist’s background, understand how and why they were doing what they did, what tools they had, and what was their training. You need to know the techniques and process of previous stone carvers.

SH: We also need to know what type of stone was used, and from what quarry it came. Preferably we can obtain stone from the same part of the quarry. The original quarries for the granite used in the monuments at Gettysburg have been closed, for the most part, for some time, making finding the correct stone a challenge. A lot of the monuments at Chattanooga are limestone, which is readily available, but the buff color that was used is a bit harder to obtain.

CWT: What kind of damage do you repair?

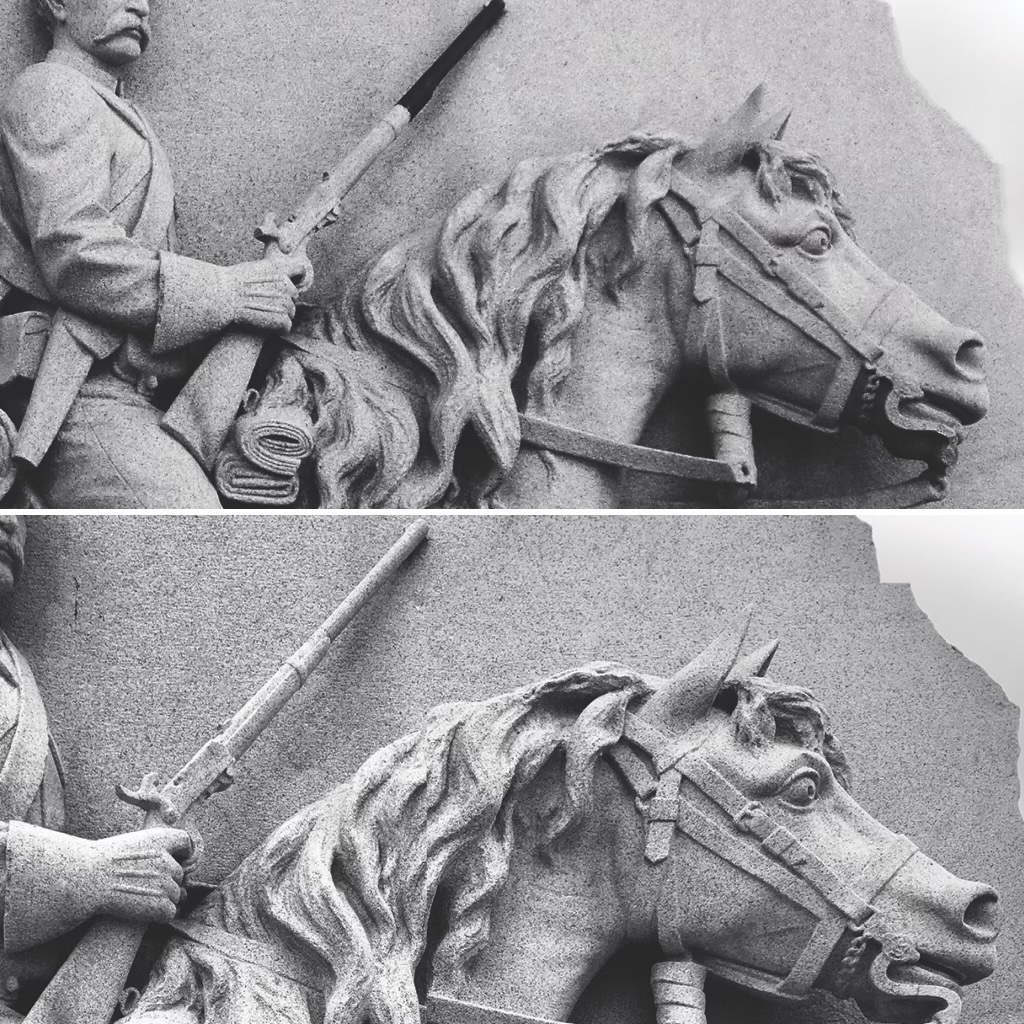

SH: Most of the monument repairs that we do are relatively small pieces—ears of horses, hammers on rifles, fingers, things that protrude from the stone that are easily broken.

MM: The directive of the Monument Preservation Branch is to tell the story of the monument but not focus on details that are not integral. It is important to keep the historic fabric of the original intact as much as possible. Deciding what must be fixed and what doesn’t need to be fixed to remain true to the story of the monument. A lot of the damage is from falling branches, some from weathering of the stone. Lucas Flickinger, supervisor of Gettysburg National Military Park’s Monument Preservation Branch, wants the story of the monument to be told. For example, the goatee is missing on the soldier on the monument to the 13th Pennsylvania Bucktails. But it was missing when it was first installed, so it is true to the story of the monument.

CWT: Can you explain the steps in your process?

SH: If there are any historic photos available, we look at those to determine what the missing piece looked like on that exact monument. We also utilize photos and actual elements of things like rifles, bayonets, spurs, etc., that were used at Gettysburg. The park is an excellent source of information and historic elements to draw from. We then make a model with clay to show what the final repair will look like. After the clay model is approved, we remove just enough stone on the monument to form a pocket or joint to attach the new piece. We carve the new piece and then attach it to the monument with stone epoxy, titanium or stainless steel pins, and color matched grout.

CWT: Where do you get stone to match the original?

MM: Most of the stone that was used in the monuments at Gettysburg is no longer quarried. Lucas Flickinger has been hunting down and stashing pieces quarried from the original sites and he provides them to match as well as possible. Most of the monuments are made of granite, but there is a wide variation in appearance.

CWT: What was the most difficult restoration on a Civil War monument for you?

MM: Carving the spheres in a row on the 21st Indiana Battery was a fun challenge. The geometry must be perfect on something like that. We carved five new cannonballs that were missing from the top. That was the Chickamauga project. The 155th Pennsylvania Infantry monument at Gettysburg on Little Round Top was the hardest monument, though. That was a single repair with parts of both hands and the end of the rifle. The difficulty piece of this was the position of the hand at the point the carving captures the loading of the gun. The soldier is just about to remove the ramrod for use. An NPS ranger was very helpful in my understanding of this process and let me video the whole process and understand the position of the hand.

SH: Carving spheres is not like reproducing something like leaves or feathers, where a slight deviation from the original would not stand out. For me, one of the biggest challenges was working on the 17th Pennsylvania Volunteer Cavalry Regiment monument at Gettysburg. The repairs included replacing a missing piece of the reins and part of the bit in the horse’s mouth. It was difficult because due to it being freestanding, floating in space, and it had to be attached in three different places, but not be visible. A complicated repair. It has to both look right and fit. We did it two years ago, and it took five days if I recall correctly.

CWT: Your work must be physically demanding.

MM: Most of the work we do on Civil War monuments is in small pieces. But they are sometimes hard to reach. The work is repetitive and you have to be good to your body.

CWT: What restoration are you most proud of?

MM: The 155th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiment monument. Tricky and complex—it was a hand touching hand on the top of the gun. Getting the stone to work was a complex problem, like the reins.

SH: I like them all, but those reins turned out pretty nice.

CWT: Have you had to work on any malicious damage?

MM: No. It is mostly damage from kids playing on the monuments, tree branches falling (or whole trees!).

That type of thing. Don’t climb on the monuments!

CWT: Do you use high-tech methods of digitization and scanning?

MM: We focus on low-impact carving, with modern tools for this work. We still use the traditional principles even if we do use grinders and die grinders. Typically, these are the best choices for the monuments because of their design. If we were carving a new sculpture, start to finish, we could use traditional methods (i.e., hammer and chisel or pneumatic gun and chisel). Working progressively from high impact to light impact. Since the Gettysburg monuments are already completed, they are now more delicate, relatively of course, and so we use low/no impact methods.

CWT: Why does stone carving appeal to you?

SH: It’s sort of a cliché, but I like to reveal the object hidden within the stone—looking at a block of stone and visualizing something inside of it. It can be a meditative process—slowly removing material until the final form is achieved. In addition to stone carving, I also enjoy modeling. It’s similar, but you’re adding material, like clay, instead of removing it. I draw and paint as well. I always say sculpting is like drawing in three dimensions.

MM: I love the reductive process. There is a zen feeling about it for me. I do have to be careful not to get too relaxed or I carve very slowly. I love drawing out a project on paper and then watching as the stone conforms to the plan. I enjoy the step-by-step nature of it. I love being a part of something bigger than myself and longer lasting.

CWT: What carved stone monument do you find especially moving?

SH: At Gettysburg, I find the 116th PA Infantry monument rather poignant—it’s not often that you see a monument featuring a fallen soldier, as opposed to an action or heroic pose.

MM: I love the Soldiers Monument. I think it is beautiful. I also like the horse on the 17th Pennsylvania Cavalry monument. I believe the carver did a great job capturing the look that would have been on its face. ✯

Interview conducted by Senior Editor Sarah Richardson.