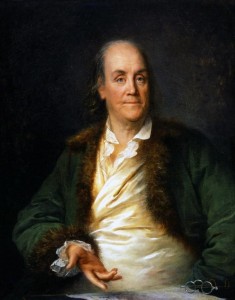

In December, 1772 Benjamin Franklin – then serving in London as an agent for four American colonial assemblies as well as the appointed Postmaster General of the colonies for the Crown – anonymously received a packet of letters that had been written to Thomas Whately, a former British undersecretary, by Thomas Hutchinson, Governor of Massachusetts. Of singular importance is a January 29, 1769, letter in which, ostensibly for the public good, Hutchinson advocated that particularly harsh actions be applied in the colony, noting that if more stern measures were not imposed, “The friends of government will be utterly disheartened [sic], and the friends of anarchy will be afraid of nothing…. There must be an abridgment of what are called English liberties.”[i]

Troubled by the implications, Franklin realized that his associates in America should be made aware of the letters’ content and passed them on to Thomas Cushing, the speaker of the Massachusetts assembly, who, in turn, showed them to Samuel Adams, a principle in the colonial revolutionary movement, the Sons of Liberty. For Adams, the missives were a propaganda windfall. While, in fact, Hutchinson said little in the letters that he had not previously stated openly, the reference to an abridgment of English liberties was particularly explosive. Over a period of weeks, Adams then skillfully prepared the public with a clever press campaign in which he promised revelations that proved the existence of a plot “to overthrow the Constitution of this Government, and to introduce arbitrary Power into this Province.”[ii]

With the citizenry breathless to see the evidence, Adams published the letters in June 1773, making sure they were disseminated throughout the colonies. As anticipated, Hutchinson’s candor regarding restricting liberty sparked revulsion and alarm far and wide. He was hanged in effigy in Philadelphia and by college students in Princeton, New Jersey, while numerous essayists equated him to the worst villains in history. Adams’ strategy had worked well indeed. For many readers, Hutchinson’s letters confirmed that London was bent on stripping the colonists of their liberty. For that matter, even some loyalists doubtless believed that their mother country was perhaps at least considering a reevaluation of the colonists’ freedom.[iii]

With the citizenry breathless to see the evidence, Adams published the letters in June 1773, making sure they were disseminated throughout the colonies. As anticipated, Hutchinson’s candor regarding restricting liberty sparked revulsion and alarm far and wide. He was hanged in effigy in Philadelphia and by college students in Princeton, New Jersey, while numerous essayists equated him to the worst villains in history. Adams’ strategy had worked well indeed. For many readers, Hutchinson’s letters confirmed that London was bent on stripping the colonists of their liberty. For that matter, even some loyalists doubtless believed that their mother country was perhaps at least considering a reevaluation of the colonists’ freedom.[iii]

But the general uproar aside, more importantly, politically, it also galvanized opposition activists and mobilized public opinion against the governor. Here at last was the smoking gun that Boston’s radicals had searched for in their long struggle to depose Hutchinson. In a matter of days, the Massachusetts General Court passed a resolution requesting the governor’s removal from office along with his lieutenant governor, Andrew Oliver. This, in addition to inspiring a gradual escalation of civil unrest and violence that, at least in part, spawned the Boston Tea Party.[iv]

In England, the release of the letters triggered charges and countercharges as to what scoundrel could have possibly been so dishonorable as to steal and publish private correspondence. A duel at swords left one party wounded and both parties aching for further satisfaction, while the British government publicly announced an investigation in order to discover who leaked the letters. Only at this point – and primarily to prevent further bloodshed – did Franklin reveal his role in transmitting the letters, writing in a letter to the London Chronicle, “Finding that two gentlemen have been unfortunately engaged in a duel, about a transaction and its circumstance of which both are totally ignorant and innocent, I think it incumbent on me to declare (for the prevention of further mischief, as far as such a declaration may contribute to prevent it) that I alone am the person who obtained and transmitted to Boston the letters in question.” However, he refused to say who gave him the letters.[v]

As a practical matter, Franklin was already a somewhat controversial figure in England, primarily due to the fact that he had become the symbol and spokesman in London of American resistance to the sovereignty of Parliament. And, as might be expected, his enemies in the British government had been waiting their chance to discredit him. Now they had it. In January 1774, he was summoned before the Privy Council, allegedly to formally present a petition from the Massachusetts Assembly asking the removal of Hutchinson as governor, but actually to be pilloried for his recent actions. The news of the Boston Tea Party had reached England only a few days earlier and an enraged ministry could ask for no better scapegoat.

It was a hostile crowd, composed mostly of lords and ladies of the realm, gathered in the appropriately named Cockpit, an adjunct of Whitehall Palace, to see the Christian fed to the lion – the lion, in this case, was the solicitor-general, Alexander Wedderburn, a brilliant, ambitious, and wily lawyer, so damaging when representing the opposition that he had been appeased with a place in government. For an hour he battered Franklin, loading him with “all the licensed scurrility of the bar and deck[ing] his harangue with the choicest flowers of billingsgate.” Franklin was a common thief and his motive in sending the letters, Wedderburn charged, was simply to become governor in Hutchinson’s stead. Franklin stood in his old-fashioned wig and suit of figured Manchester velvet, enduring in silence the insolent attack: “The Doctor seemed to receive the thunder of [Wedderburn’s] eloquence with philosophic tranquility and sovereign contempt.” Of course, no defense was really possible, as he had already admitted transmitting the letters: “I made no justification of myself,” Franklin later wrote, “but held a cool, sullen silence, reserving myself to some future opportunity.” The Massachusetts charges against Hutchinson were perfunctorily dismissed by the Privy Council as “groundless, vexatious and scandalous and calculated only for the Seditious Purpose of keeping up a spirit of clamour and discontent.” The next day Franklin was fired from his postmastership.[vi]

Franklin recognized that his usefulness as agent of the Massachusetts Assembly had been destroyed, and he resigned at once, leaving the agency to Arthur Lee, an irascible Virginian whom Massachusetts had earlier deputized to help him. But when Lee departed for a tour of the Continent, Franklin stayed on to give “what assistance I could as a private man.” Whatever offices he held or did not hold, he could never really be a merely private man. He was still the embodiment in London of the bad Americans whom the British would have to deal with across the ocean.[vii]

Franklin returned to America, arriving in Philadelphia on May 5, 1775, where, by that time, the American Revolution had begun in earnest against a backdrop of open fighting between colonials and British soldiers in Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts. He was greeted with public displays in Boston and other colonial cities that clearly indicated that the Americans – doubtless in response to his drubbing in the Cockpit – had found a visible hero. Within two days of his landing in Philadelphia, his fellow Pennsylvanians unanimously chose Franklin as their delegate to the Second Continental Congress, and in June 1776, he was appointed a member of the Committee of Five that drafted America’s Declaration of Independence. Thus Franklin’s new career began: as one of his country’s most senior founders who would also serve with peculiar effectiveness as America’s first foreign emissary on a commission to France charged with the critical task of gaining French support for American independence.[viii]

For his part, by the summer of 1773, Thomas Hutchinson was ready to retire, convinced that he could do no more to resist the conspiracy for independence. Although he remained convinced that his letters demonstrated no maleficence on his part, he also acknowledged that he could no longer significantly influence either public opinion or, perhaps more importantly, the Massachusetts colonial political system. While refusing to admit to having done anything wrong, by mid-July he eagerly anticipated being replaced, “more than a war horse feels when his heavy accoutrements are to be taken off and he sees a quiet stable or pasture just by him.”[ix]

For his part, by the summer of 1773, Thomas Hutchinson was ready to retire, convinced that he could do no more to resist the conspiracy for independence. Although he remained convinced that his letters demonstrated no maleficence on his part, he also acknowledged that he could no longer significantly influence either public opinion or, perhaps more importantly, the Massachusetts colonial political system. While refusing to admit to having done anything wrong, by mid-July he eagerly anticipated being replaced, “more than a war horse feels when his heavy accoutrements are to be taken off and he sees a quiet stable or pasture just by him.”[ix]

Indeed, the publication of his letters, and the attendant public denunciation, disgusted the private and proper gentleman politician. In August 1773, Hutchinson wrote to Lord Hillsborough, no longer in office but still an influential figure, for help, requesting that “before my removal I humbly hope, however, I shall be honorably acquitted and that I shall not be left wholly without employment and support in advanced life, for my private fortune is not sufficient unless I sink below the moderate living I had always been used to before I came to the chair.” He added, “If by the arts of my enemies or from any other cause my interest is lessened with the Administration I would not wish to continue in so difficult a service much longer and I would endeavour to obtain some provision for my future support.”[x]

Thomas Hutchinson witnessed the war from London, having gone into exile six months after the Boston Tea Party. He never returned to his native America; but his years in England were bittersweet. For a short time he consorted with various ministerial figures, but soon they largely abandoned him, as if he had been the cause of their innumerable imperial and diplomatic woes. Moreover, some of his former associates went so far as to shamelessly accuse him of some measure of personal responsibility for the revolution itself due to his shortsighted policies.

Hutchinson lived on for five despondent years in Britain. Each year he found himself treated more and more as an outsider, and when some former ministers with whom he had dealt while he held power could not even remember which colony he hailed from, Hutchinson was overwhelmed with the sense that he was residing in some faraway alien land. Thirty days after the loss of Charleston in 1780, at America’s low ebb in its ongoing war, Hutchinson died in London of a stroke at age sixty-nine.[xi]

Brett F. Woods, Ph.D., is a professor of history for the American Public University System. He received his doctorate from the University of Essex, England.

[i] Thomas Hutchinson, 20 January 1769,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-20-02-0282-0007.

[ii] John Ferling, Whirlwind: The American Revolution and the War That Won It (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2015), Kindle 1765-1779.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Andrew Stephen Walmsley, Thomas Hutchinson and the Origins of the American Revolution (New York: NYU Press, 1998), 145.

[v] “Franklin’s Public Statement about the Hutchinson Letters, 25 December 1773,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-20-02-0272

[vi] Claude-Anne Lopez and Eugenia W. Herbert, The Private Franklin: The Man and His Family (New York: W. W. Norton, 1975), 195.

[vii] Edmund S. Morgan, Benjamin Franklin (Princeton: Yale University Press, 2002), 203.

[viii] Kenneth Lawing Penegar, The Political Trial of Benjamin Franklin: A Prelude to the American Revolution (New York: Algora, 2011), 166.

[ix] Walmsley 1998,146.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] John Ferling, A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 483.