Not a few readers first encountered Stewart Brand in the opening scene of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Tom Wolfe’s whirligig chronicle of the Merry Pranksters, Bay Area refugees from the humdrum who in the early 1960s coalesced around novelist Ken Kesey and a passel of hallucinogens, including LSD, then legal. Wolfe opens his tale in late 1966 in the bed of a pickup truck rocketing around San Francisco. With Wolfe are a crazily garbed kid called Cool Breeze, a young woman known as Black Maria, and “a half-Ottawa Indian girl named Lois Jennings, with her head thrown back and a radiant look on her face. Also, a blazing silver disk in the middle of her forehead alternately exploding with light when the sun hits it or sending off rainbows from the diffraction lines in it.” Driving the truck, whose bumper sports a sticker reading “Custer Died for Your Sins,” is “…Lois’s enamorado Stewart Brand, a thin blond guy with a blazing disk on his forehead, too, and a whole necktie made of Indian beads. No shirt, however, just an Indian bead necktie on bare skin and a white butcher’s coat with medals from the King of Sweden on it…”

That was Brand at 27, happily but temporarily ensconced in one of his substitute families. Wolfe initially meant to profile Kesey but his research ran away with him. By the time Acid Test debuted in 1968, Brand, who as with all his affiliations was in the Pranksters but not of the Pranksters, had moved on. Moving on, as John Markoff engagingly documents in Whole Earth, is what Stewart Brand has always done best, with sometimes prescient, often spectacular result. A scion of a Rockford, Illinois, family whose antecedents had made a comfortable amount of money in lumber and hardware, Brand was a midwestern mandarin edition of that classic American type, the walking contradiction: a polymath given to serial obsessions, a gifted leader made itchy by crowds; an innovator who chafed at having to keep his creations on the rails; a conservative soul with an anarchic bent. Before allying with the Pranksters, Brand had grown up the youngest child of an engineer-turned-advertising man, prepped at Phillips Exeter, attended Stanford, been a U.S. Army paratroop officer—to his endless chagrin, he washed out of Ranger school—a freelance writer and photographer, an organizer of events social and artistic, and auteur of a multimedia show he titled America Needs Indians! For Kesey and ilk, Brand put together the Trips Festival, an epochal acid-drenched extravaganza that helped launch the hippie phenomenon, lent the Grateful Dead propulsion, and pointed Bill Graham toward the life of a countercultural impresario. While tripping in February 1966 Brand was moved to ask himself, “Why haven’t we seen a photograph of the whole earth yet?”

His rhetorical query begat the Brand-helmed Whole Earth Catalog, a best-selling 1970s paperback compendium of endorsements for tools, books, riffs, gear, and philosophy that Steve Jobs called “Google before there was Google.” Anyone who ever cracked a copy of the catalog, hunting, say, rural real estate, and came upon $50-an-acre land through the United Farm Agency, or, needing to know how to repair VWs, had at hand a copy of John Muir’s How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive: A Manual for the Compleat Idiot when a Microbus’s accelerator cable snapped east of Berlin, Ohio, on Labor Day weekend 1971, will appreciate this deeply researched and empathetic portrait of a truly original character who, among other coups, coined the phrase “personal computer.”

In Whole Earth, Markoff, a former New York Times reporter and author of Machines of Loving Grace, What the Dormouse Said, and other books, acknowledges, accepts, and succeeds at the formidable challenge of portraying each successive variant on the Brand brand; by the way, brandwise, this is an authorized biography. As Markoff puts it in his subtitle, across the last half century and then some there have been many Stewart Brands, each invented by the man himself, not infrequently in evolutionary reaction to his preceding incarnation—a restlessness that extended to putting himself at a distance from his family of origin (though accepting as his due modest infusions of family dough to fund his various enterprises). “Stewart has always wanted to be at the cutting edge, and he’s trapped there,” older brother Mike said ruefully. Perhaps seeking successors to that original familial group, Brand has worked serially at developing connections with other clans and tribes. He is a Venn diagram of selves and latter 1960s American and global eras. Besides his paratrooper-into-Prankster phase and those preceding it, Brand, 84, has changed lanes from editor and publisher to political strategist to eco-warrior to conservationist to digital visionary to corporate consultant to author, always striving to adhere to an adjuration of his that admirer Jobs adopted: “Stay hungry. Stay foolish.” Whole Earth locates Stewart Brand and his remarkable array of experiences and impacts in the larger context of the history he has lived through and influenced.

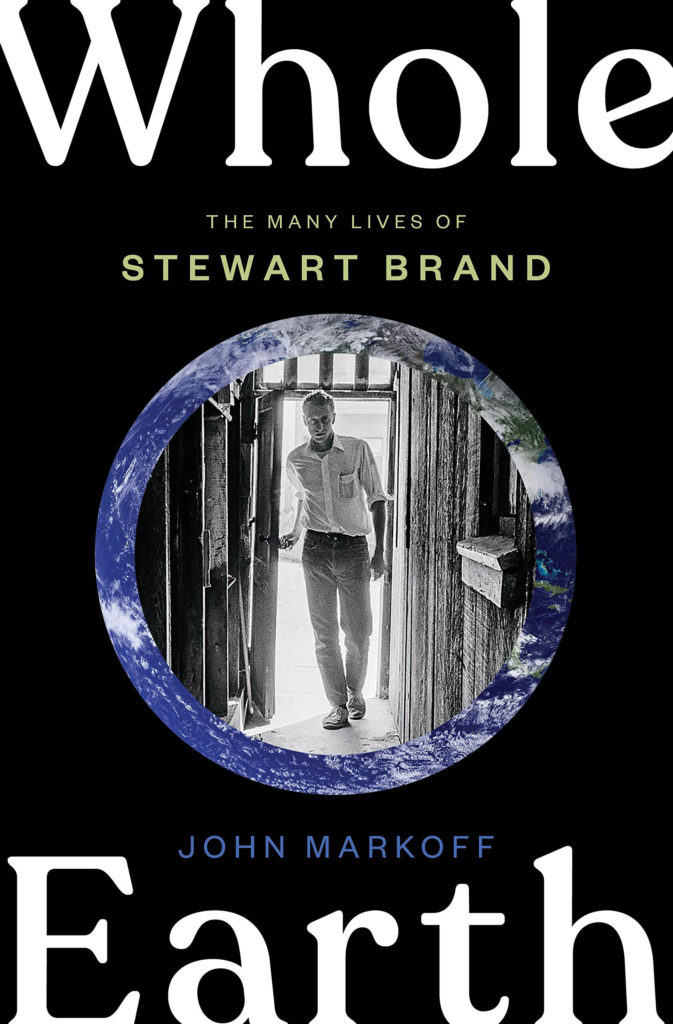

Whole Earth: The Many Lives of Stewart Brand

By John Markoff

Penguin, 2022

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.