Years of research reveal the fascinating story of a Union bugler.

It is estimated that more than 20,000 Hispanics or persons of Hispanic descent served in the American Civil War. To serious students of the conflict, the names and stories of some of these individuals are relatively well-known. There was, for example, Lt. Col. Henry Pleasants of the 48th Pennsylvania, who in the summer of 1864 masterminded the Petersburg Mine. Pleasants was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, the son of an American father and Hispanic mother.

Other famed soldiers of Hispanic descent included Cuban-born Lt. Col. Julius Peter Garesche, chief of staff to Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans, who was killed in action at the Battle of Stones River; Luis Emilio, the son of a Spanish immigrant, who served as a captain in the 54th Massachusetts Infantry; and the Cuban-born Cavada brothers—Adolfo, an aide-to-camp to Union Maj. Gen. Andrew Humphreys, and Federico, lieutenant colonel of the 114th Pennsylvania who was captured near the Peach Orchard at Gettysburg and later confined in Richmond’s Libby Prison.

John Ortega of Spain and Philip Bazaar of Chile, both seamen in the U.S. Navy, received Medals of Honor for meritorious service—the latter for bravery during the assault on Fort Fisher and the former for his daring while serving onboard USS Saratoga. But while the stories of these individuals may be better known, most of those of Hispanic descent who served in the Civil War were neither commissioned officers nor Medal of Honor recipients, but enlisted men whose stories remain to be discovered and yet to be told, soldiers like Emerguildo Marquis, who served as a bugler in the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry and whose story, as it turned out, took quite a long time to unfold.

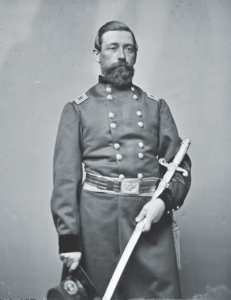

I first happened upon his name many years ago while I was researching a Union general named James Nagle who hailed from Pottsville, in my native Schuylkill County, Pa. During the Civil War, Nagle, a wallpaper hanger and house painter by profession, raised no fewer than four volunteer infantry regiments and as a brigadier general, led his men in attacks against the Unfinished Railroad at Second Bull Run, at Antietam’s Burnside Bridge, and against Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg. Being well familiar with his military record, I was hoping, all those years ago, to learn more about Nagle the man and not the soldier, and so I began my search by examining the Census records of 1840, 1850, and 1860. And that is when I first happened upon the name Emerguildo Marquis.

In the Census records of 1850 from Pottsville’s Northwest Ward, I located the entry for James Nagle, identified then as the “Head of Household,” 28 years old; his wife, Elizabeth, was 29, and their three (of eventually seven) children were named Emma, age 7, George, age 5, and the baby, James Winfield Nagle, age 1. But then, much to my surprise, I saw the name of yet another child living in the home, an 11-year-old boy named Emerguildo Marquis, born in Mexico. My curiosity piqued, I could only then wonder who exactly was this boy and how did he end up living in the Nagle home in Pottsville, in the heart of anthracite coal country Pennsylvania?

Knowing that a young James Nagle had served in the Mexican War as Captain of the Washington Artillerists, a militia company that became Company B, 1st Pennsylvania Volunteers, my first thought, naturally, was that Emerguildo had journeyed to Pottsville with Nagle when the company returned home in the summer of 1848. Nagle had originally formed the Washington Artillery in 1842, had trained it and drilled it, and then, in December 1846, had set off with it to war in Mexico. With Nagle in command, the company formed part of General Winfield Scott’s force as it fought its way from Vera Cruz to Mexico City in the spring and summer of 1847, seeing action at such places as Cerro Gordo, Puebla, and Huamantla. Surely, I thought, Nagle and Emerguildo had happened upon one another somewhere along the way. Naturally, though, I wanted to find out for certain and this led to a many years’ journey to discover more about this Mexican-born boy named Emerguildo.

Because of Nagle’s extensive Civil War service record, the thought crossed my mind that perhaps Emerguildo, who would have been about 22 years old in 1861, had served in that conflict but I knew for a fact that I had never before come across his name while studying any of the company rosters of the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry, the regiment Nagle raised in the summer of 1861. But perhaps, I thought, Emerguildo served in one of Nagle’s other regiments.

Nagle’s first command in the Civil War was the 6th Pennsylvania Infantry, a three-month regiment, which in the spring of 1861 was assigned to George Thomas’ brigade in Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson’s small army in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. Examining the muster rolls of this 90-day unit I discovered in the ranks of Company G, 6th Pennsylvania, a private named not Emerguildo Marquis, but “M. Emrigeuldo” instead. This had to be the same person, I thought. Convinced now that he had served in the Civil War, my next step was to contact the National Archives in Washington and request copies of his service records. Several weeks later, and hopeful that I had included enough possible variations of spellings of his name (Marquiz, Marquis, Marqueese), a copy of Emerguildo’s file arrived at my door.

His service records did much more than simply confirm that he had, indeed, served as a private in the 6th Pennsylvania Infantry, for along with his records for his three months’ service with the 6th Pennsylvania were records from his service as a bugler in the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry, a “three-years or the war” regiment. This was the first time I discovered that Emerguildo had also served in the cavalry, as a company bugler. Also contained in his service records was a letter written by James Nagle. The letter was dated December 22, 1862, and by then Nagle had been promoted to brigadier general, and placed in command of the 1st Brigade, 2nd Division, 9th Corps.

Wrote Nagle: “I have the honor to make application to have Emerguildo Marquis, Bugler in Captain White’s Company 3rd PA Cavalry, detailed as bugler and orderly, for these Hd. Qrs. He is a Mexican Boy that I brought along from Mexico. He was with me in the three months service, after that he enlisted in the Cavalry, and he is now desirous of joining me in some capacity, and I only have three mounted orderlies, and need a bugler at Head Quarters to sound the General Calls.”

So, there it was, confirmation of my initial assumption that Nagle had brought Emerguildo home to Pottsville from his service during the Mexican War. Nagle’s request was granted and Emerguildo became a member of General Nagle’s staff. I was struck by the fact that Emerguildo was a bugler, for the Nagle family was very much musically inclined. In his younger days, James Nagle was a fifer; his brother, Daniel, was the drummer of the militia company James had organized and led off to Mexico, and his other brothers, Levi and Abraham, were both musicians who both served in the regimental band of the 48th Pennsylvania. Music must then have been an important part of the Nagle family upbringing and household and one can only imagine the family teaching a young Emerguildo how to play.

For a long time thereafter, this was all the information I was able to compile on Emerguildo but, still, his story intrigued me. I thought that perhaps someday I would discover more about him. As it turned out, that someday was in April 2007, when I met John Nagle, the Civil War general’s great-great-grandson. He and I had been in contact via e-mail for years prior to this, but this was the first time we had met and when we did on that April day, he very kindly brought along with him numerous old documents: letters, diaries, etc., all related in some way to James Nagle, a veritable treasure trove. “The General and his family never threw anything away,” he joked.

Included among the many documents was Emerguildo Marquis’ original discharge certificate. As it turned out, Emerguildo was discharged from the service on August 24, 1864, upon the expiration of his three-year term of service with the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry. The document also stated that Emerguildo had been born in Mexico, that he was 26 years of age, stood 5’1” in height, had a dark complexion, black eyes, and black hair. And his occupation? A painter. A painter, just like General James Nagle.

Most revealing, however, was a handwritten account of James Nagle’s service in the Mexican War, penned by his youngest daughter, Kate, which at last answered the question about just where Emerguildo came from and how he ended up in Pottsville with the Nagle family. As Kate Nagle recorded, the summer of 1848:

“…was a long sad time for folks at home, but great rejoicing when word came that the war was over and the Army was waiting for orders to move; and greater was the joy when a telegram came saying Come to Philadelphia with the children to meet us….A number of the wives of the Soldiers went to Philadelphia to meet their husbands. When they met them, they saw three persons who were not Soldiers, but little Mexican boys about 9 or 10 years of age. They were very small, dark skin, no shoes….They learned to love the Soldiers, and when they broke Camp the little boys followed them (stole their way, so to speak). When they were discovered the Army was miles out of the City of Mexico. They would not go back. They were little orphans, and the Officers took charge of them and landed them at home in Pottsville. Captain [James] Nagle, Lieut. Simon Nagle, and Lieut. Frank B. Kaercher, each took a little Mexican boy to their homes. The one Captain Nagle cared for was, by name, Emerigildo Marquis, known as ‘Marium.’ He was treated as one of the family. He was sent to school, sent to learn a trade….He was away from home to work, but never forgot the family; he came home very often over the week ends. He…grew up with the family. He loved Father & Mother Nagle, and the Children all loved him.”

I could hardly believe what I was reading. After years of searching, it felt like the end of a long, long journey to read these words, written by General Nagle’s own daughter about Emerguildo and confirming what I had initially assumed years back when I first came across Emerguildo’s name: that Nagle must have brought him back from Mexico and raised him in Pottsville in his home, as one of his own; and now I knew that he must have also taught him music and the painter’s trade. For me, it felt like quite the “discovery.” Little did I know that just a few days later, I was to make yet another discovery about Emerguildo Marquis.

I first wrote about Emerguildo’s fascinating story as it unfolded to me over the years on my website (www.48thpennsylvania.blogspot.com) and in late 2020, the story was happened upon by Frank Jastrzembski, a historian who also heads a nonprofit organization called Shrouded Veterans. Recognizing that there are thousands of veterans from the Mexican War and Civil War buried in unmarked graves, or whose tombstones are “sadly in disrepair,” Jastrzembski and Shrouded Veterans works to ensure that these veterans “are no longer neglected.” Noting the condition of Emerguildo’s original tombstone, Jastrzembski, coordinating with Tom Shay from the Pottsville Presbyterian Cemetery and the United Presbyterian Church, secured a new headstone from the Department of Veterans Affairs (above), which in the spring of 2021 was placed at Emerguildo’s final resting place.

I first wrote about Emerguildo’s fascinating story as it unfolded to me over the years on my website (www.48thpennsylvania.blogspot.com) and in late 2020, the story was happened upon by Frank Jastrzembski, a historian who also heads a nonprofit organization called Shrouded Veterans. Recognizing that there are thousands of veterans from the Mexican War and Civil War buried in unmarked graves, or whose tombstones are “sadly in disrepair,” Jastrzembski and Shrouded Veterans works to ensure that these veterans “are no longer neglected.” Noting the condition of Emerguildo’s original tombstone, Jastrzembski, coordinating with Tom Shay from the Pottsville Presbyterian Cemetery and the United Presbyterian Church, secured a new headstone from the Department of Veterans Affairs (above), which in the spring of 2021 was placed at Emerguildo’s final resting place.

After meeting with General Nagle’s great-great-grandson, I took a trip up to Schuylkill County to visit my family and to gather some photographs of gravestones in Pottsville’s Presbyterian Cemetery. For years I had wondered where Emerguildo had been laid to rest since I had never before happened upon his grave in all my cemetery wanderings. The caretaker of the Presbyterian Cemetery, Tom Shay, told me that Emerguildo was, in fact, interred therein, as had been John Nagle. As I wandered around the graveyard, I came across the gravesites of General Nagle’s parents, Daniel and Mary, who are buried next to two of their daughters, Eleanor and Elizabeth. Two of the four of these Nagle family headstones were knocked over, and a third was severely leaning. Then I noticed at the foot of the grave of the Nagle sisters was a stone sunken deep into the ground. With the assistance of my family who were with me that day, we removed the dirt and grass that was covering the stone. And there it was, inscribed upon the stone and underneath years of dirt and grass was the name “Emerguildo Marquis.” Within the course of just one week, Emerguildo’s story was at last told and his grave “found.” The grave also revealed something else; that Emerguildo had died in 1880 at the much-too-young age of 42; the cause of his death, however, I have not yet been able to ascertain. He was buried with the rest of the Nagle family, another testimonial that he was, indeed, considered a member of the family.

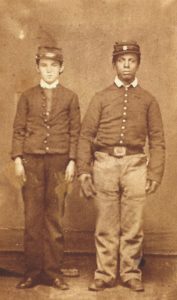

After carefully setting the stone upright, I left to purchase a small American flag to place at his grave; he was, after all, a soldier who had served his country in the three-month 6th Pennsylvania Infantry, the three-year 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry, as well as on General Nagle’s staff. And of his service, Emerguildo was justly proud. In July 1862, while encamped at Harrison’s Landing with the 3rd PA Cavalry, Emerguildo was shocked to read of his own death in an issue of Pottsville’s Mining Record newspaper, and was infuriated, it seems, that the article had referred to him as a “servant” of company commander Captain J. Claude White. He was determined to set the record straight in both respects, by writing to the editors of the Record’s rival newspaper, the Miners’ Journal:

Harrison’s Landing, Va, July 22d, 1862,

Editors Miners’ Journal: I wish to state, that having read a copy of the Mining Record this evening, I was greatly surprised at seeing the statement of my death, and that I am a servant to Captain White. Both these statements are utterly false. I did not enlist to be a servant, except to the country of my adoption. I wish also to state, that servants generally do not go so close to the mouth of cannon as to incur the risk of being killed by balls from rebel guns. I would state, also, that the gallant Colonel Nagle never brought me to this country to be a slave, sooner than be which, I would go home again to my native country, and assist my brave countrymen to drive the French invaders from the soil.

The truth is, that Daniel Wehry, of Donaldson, a private in our Company, was killed by a solid shot, and that the Captain’s horse was killed in the same shot.

Emriguildo Marques alias The Young Mexican Bugler, of Co. L, 3d Penna. Cavalry

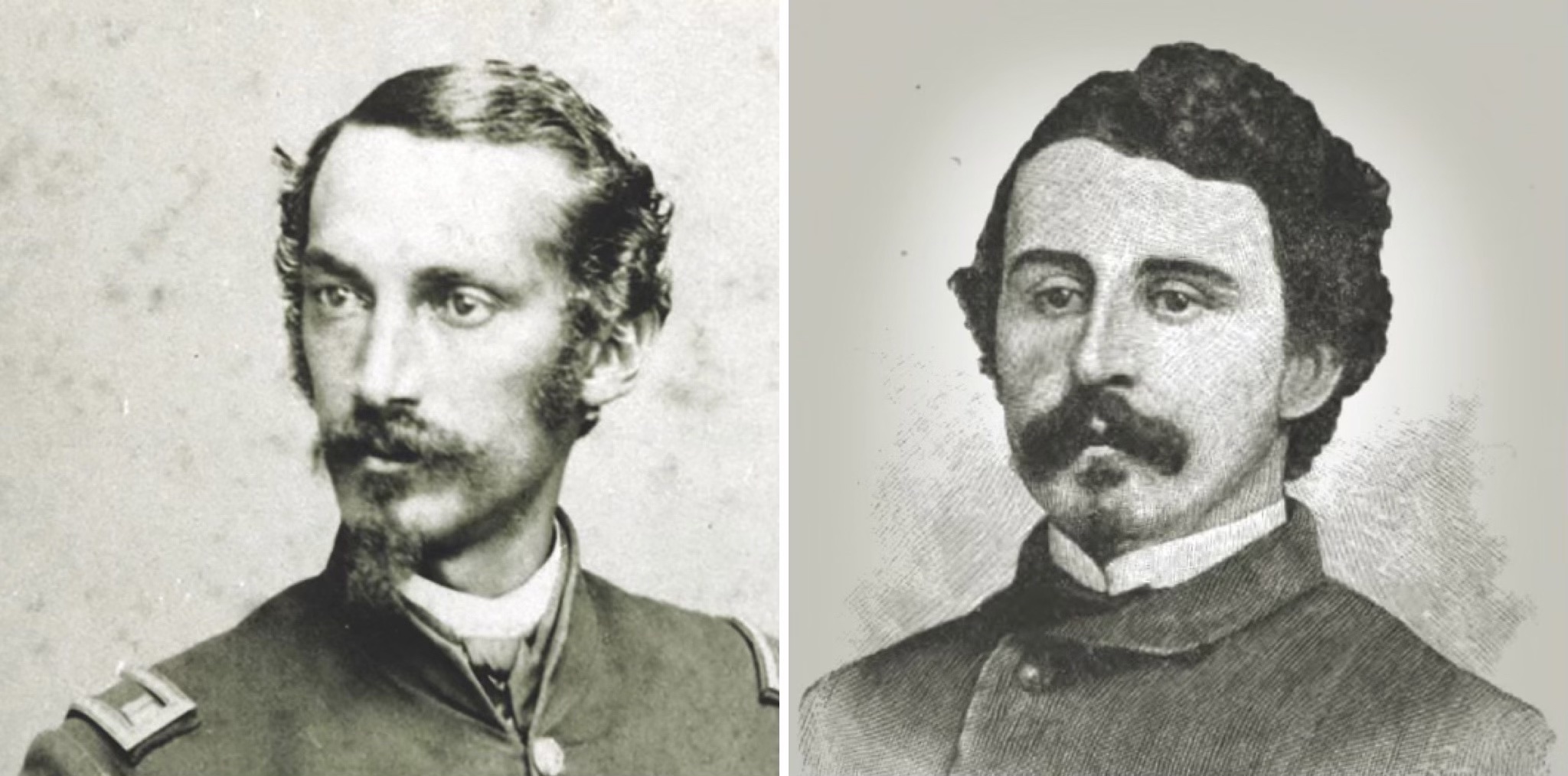

With the information found in the Census records, upon his tombstone, from his service records, and from the notes left behind by family members, I felt comfortable that the story of Emerguildo Marquis could be fully told. But even after all the years of searching, and waiting for his story to unfold, still, in the back of my mind, there was another piece of this puzzle missing. I naturally wondered if any photographs of Emerguildo existed and so I asked John Nagle, the general’s great-great-grandson, if he had ever seen any image of Emerguildo and if any still existed. Yes, he replied. He was certain of it. He just had to find them, wherever they might be.

Weeks went by, then months, and ultimately years; and, then, an e-mail arrived: he had found them! Pictures of Emerguildo Marquis, including one in uniform, standing next to James Winfield Nagle, one of General Nagle’s sons. For someone who searched all those years, trying to “discover” Emerguildo Marquis, seeing his face was quite the remarkable moment.

John Hoptak is the author of several books, including The Battle of South Mountain, Confrontation of Gettysburg, and Dear Ma: The Civil War Letters of Lt. Curtis C. Pollock.