Antebellum army experimented with ships of the desert

ON A SPRING MORNING IN 1883, a homesteader near Eagle Creek in southeast Arizona left her adobe house to fetch water. Suddenly, the woman screamed. From inside the house, a second woman had looked out to behold a huge, strange red animal with a rider on its back. The second homesteader barricaded the door and began to pray. At nightfall, menfolk returned from hunting sheep stolen by Apaches to find the would-be water carrier trampled to death and surrounded by huge cloven footprints. A few nights later, several miles northeast, two prospectors awoke terrified as a beast stove in their canvas shelter. Clambering to their feet, the pair watched a large, ungainly animal gallop off, leaving a trail of cloven prints and, snagged on brush, tufts of red hair, inspiring legends of the “Red Ghost.”

The mystery beast’s presence in the Southwest of the 1880s dated back four decades, to a time when westbound pioneers confronted the Rockies, the Sierras, and vast deserts between as they trekked toward the rich valleys of coastal California and Oregon. Pioneers crossed the continent using three main routes: the northerly Oregon and Humboldt trails, each originating in Missouri; and the southerly Gila Trail, starting from El Paso, Texas and traversing New Mexico and Arizona to Southern California through fry-pan hot Indian territory.

Migrants depended on draft and pack animals. Horses were suitable for short stretches but required grain to supplement local forage. Oxen were sturdier, cheaper, and

more dependable, but maddeningly slow. Mules, though stubborn, seemed the best bet: stronger, hardier, less picky about food and slower to thirst. Their flinty hooves easily negotiated mountain and prairie terrain; and their tough hides withstood saddle and harness abrasions. To protect western pioneers from Indians, America’s fledgling Army established cavalry outposts along the main trails. Provisioning these isolated garrisons challenged military logisticians, particularly in the “most irksome desert for beasts in the world,” as one Army quartermaster called the New Mexico terrain surrounding Fort Yuma. And once established out West, homesteaders needed a way to stay in touch with one another and folks back East. That meant reintroducing the camel to America.

North America had been the home of the original camels, which stood scarcely a foot high. Evolution wiped out those prehistoric North American ancestors, but their descendants, double-humped Siberian and Chinese Bactrians and speedy, single-humped North African Arabians called dromedaries became essential to transport and commerce in those regions.

Spanish and English colonists in America imported a few camelidae specimens for tasks like hauling ore. These experiments failed but the era of westward expansion revived interest. As early as 1837, U.S. Army Captain and Seminole War veteran George H. Crosman was advocating that the military import and test camels. Crosman corresponded with E.F. Miller, a general’s son, who shared his enthusiasm. The two envisioned in the seven-foot-tall, half-ton camel an ideal means of negotiating America’s deserts.

With its dexterous lips and razor teeth, a camel would eat virtually anything. The animal’s series of regurgitant stomachs consumed every mote of nutrient and moisture. Humps stored fat, a reserve drained as needed until the hump turned flaccid. A camel ordinarily drank its fill every three days but could survive much longer. Camels’ hardened feet need not be shod; and they are so sure-footed that desert armies mounted light artillery on them. Capable of proceeding at 10 mph without a load, a heavily burdened camel slowed considerably but still was able to travel 12 hours without pause. With proper care, a camel lived 40 years, compared with horses at 30, mules 27, and oxen 20. In the 1800s, average human lifespans approximated the camels’—allowing long and productive cross-species partnerships.

Crosman and Miller failed to impress U.S. Quartermaster General Thomas S. Jesup, but the case for camels eventually gained new urgency. The United States had acquired vast stretches of Southwest territory after defeating Mexico in the 1846-1848 conflict, whereupon prospectors combing the conquered territory discovered gold and silver deposits. Mexican War veterans like Quartermaster Corps officer Henry C. Wayne, knowing the terrain’s rigors and weather, recognized the camel’s suitability. Still, Jesup resisted.

Camel adherents finally found a welcoming ear in U.S. Senator Jefferson Davis (D-Mississippi). Davis, whose first wife had been a daughter of Zachary Taylor, had fought in Mexico alongside “Old Rough and Ready.” Named secretary of war in 1853 by President Franklin Pierce, Davis asked Wayne to make a case to Congress for camel transport. In his formal report, Wayne included a martial option: fleet Arabians might be used against Indians in “promptly punishing their aggressions.” Congress balked. However, newspaper editors, lecturers, and authors fostered the idea until, in 1855, the U.S. House of Representatives appropriated $30,000—today, roughly $900,000—for the “purchase and importation of camels and dromedaries for military purposes.”

Davis set to work, naming Wayne director of the Camel Military Corps and arranging for U.S. Navy storeship Supply, fresh from Commodore Matthew Perry’s sally to Japan, to undertake a camel-buying expedition in the Mediterranean. Wanting recommendations for a suitable skipper, Davis turned to Edward F. Beale, a Mexican War Navy veteran who also had explored Death Valley with frontiersman Kit Carson. Beale nominated a kinsman: Lieutenant David Dixon Porter, a scion of a nautical family whose ranks included adoptive brother David Farragut.

Wayne, carrying orders from Davis to buy both Bactrian and Arabian specimens, sailed for Europe in spring 1855 to consult with zoologists before joining Porter late that July aboard Supply at La Spezia, Italy. The plan was to sail to Tunis, acquire a camel, and study “its management on shipboard.” In North Africa, Porter and Wayne connected with Gwinn H. Heap, Porter’s brother-in-law and Beale’s close friend. Son of camel expert Samuel Heap, former American consul at Tunis, Gwinn knew the region, knew camels, and possessed the skill to illustrate the expedition’s travels.

At Tunis the Americans bought a camel. In addition, the local bey gifted them two more. The dromedaries adapted well to life at sea. Tethered below, the animals gave “very little trouble, very much less than a horse,” Heap reported. After pauses to dock in Malta, Smyrna—now Izmir, Turkey—and Salonika—now Thessaloniki, Greece—Supply arrived at Constantinople, now Istanbul, Turkey, in October 1855.

Demand generated by forces fighting the war in Crimea made camels too expensive for the Americans, but British demonstrations of Bactrians’ and Arabians’ performance convinced Wayne to stick with dromedaries. The party sold two of the test camels then sailed for Alexandria, Egypt, arriving late in November.

The Americans soon learned about camel idiosyncracies. Shady camel merchants disguised sick or overworked stock by blowing air through a reed to inflate limp humps. Camels’ ear-piercing groans, especially while being loaded, carried for miles. Worse, “furious excitement” seized bull camels during a prolonged rutting season. Males’ eyes reddened and mouths projected bladder-like membranes emitting burbling sounds like a human breaking wind. The sex-crazed beasts jousted among themselves and assaulted handlers, vexing their American stewards. In defense, Wayne hired three indigenous drovers to assist Albert Ray, his American wrangler. Egyptian dromedaries were cheap but Egypt was stingy with export permits—until the Americans proffered gifts: two rifled muskets, ammunition, and a mold for casting Minié balls.

Carrying ten dromedaries, Supply left Alexandria in January 1856 for Smyrna, where Gwinn Heap was already shopping. He greeted

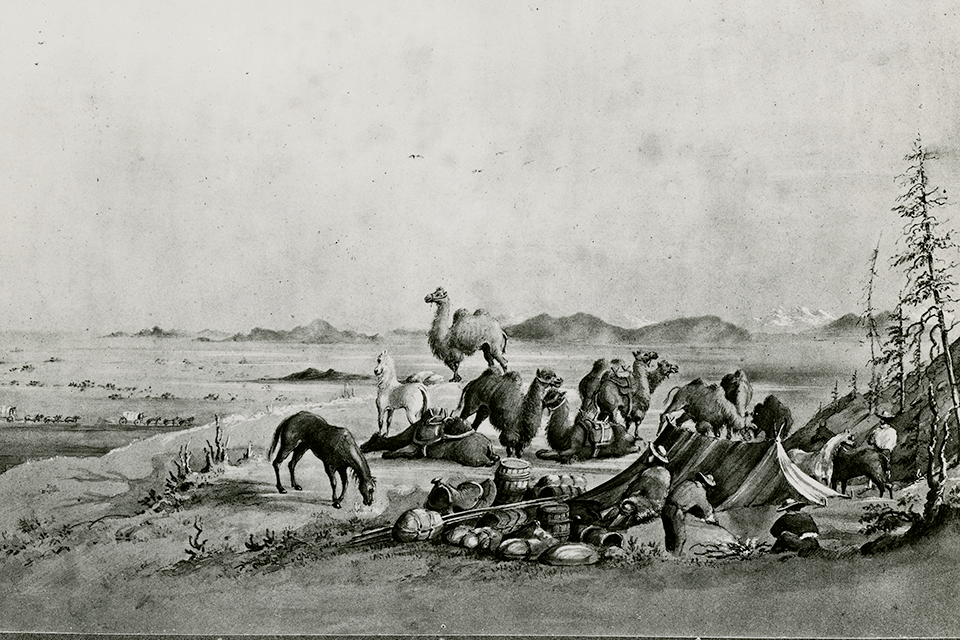

Supply with a 21-animal herd: 19 Arabians—15 male, 4 female—one Bactrian, and one mixed-breed “Booghdee.” Wayne figured a Bactrian would mollify his boss, Davis. When Supply departed Smyrna for America on February 15, Wayne’s stock, augmented by the birth of an Arabian and purchase of another Bactrian, numbered 33. Wayne had spent only a third of the funds allotted. Storms plagued Supply all the way back. Of six calves born at sea, four died as did a birthing female. On May 14, 1856, 34 camels stepped ashore at Indianola, Texas, a small Gulf Coast port. As Porter and Heap arranged another buying trip, Wayne launched the Camel Military Corps experiment.

In the days ahead, while Wayne’s beasts made a few friends, they encountered many more skeptics and outright detractors. Watching a dromedary kneel so a drover could load it with two 300-pound hay bales, Indianolans guffawed. The animal wouldn’t rise, much less move. Once handlers increased the load to four bales of hay, however, the beast calmly stood and strode off.

After acclimating his charges for three weeks, Wayne set out for the interior. Outside Victoria, Texas, Wayne met Pauline Shirkey, 10. He gave the girl’s mother, Mary, camel hair clippings from which she spun thread and knit socks—a gift Wayne sent to President Pierce. Before the caravan departed for San Antonio, Pauline took a memorable ride. “The camel bells were jingling…and I was sitting on the back of this unusual steed,” she marveled 75 years later.

Most locals shied away from the animals’ odor, noise and, not least, their ability to terrify other livestock. A camel’s scent, an expert noted, “was more easily imagined than described.” Presaging the tactic associated with early automobiles, Wayne sent a horseman ahead. “Get out of the road!” the rider would shout. “Camels are coming!”

By the time the camel herd settled at Camp Verde, an Army post sixty miles northwest of San Antonio, the animals had demonstrated the advantages they offered the army. Once away from populated areas, Wayne advised Davis, camels delivered high-capacity, low-consumption, long-range desert transport for freight, mail, even infantry. The versatile creature could also “be mounted with a small gun throwing shrapnel.”

Wayne and Davis diverged on what came next. Wayne favored patient breeding; Davis wanted immediate full-scale testing. Orders were orders, but Wayne, sensing changes ahead, looked to transfer. Denied re-nomination for the 1856 presidential election, incumbent Democrat Pierce yielded the party reins—as well as the presidency—to James Buchanan. Davis subsequently lost out in a March 1857 cabinet shakeup. He was replaced by former Virginia governor John B. Floyd just as David Porter and Gwinn Heap were delivering 41 additional camels to coastal Texas. Accompanying the beasts were 10 foreign contract workers; notable among them were two Turks—

Hadji Ali and Elías—and Greek-born George Caralambo. Having completed their contractual obligations, Porter and Heap moved on as did Wayne who, after turning over the Corps to Captain Innis N. Palmer, transferred to Philadelphia.

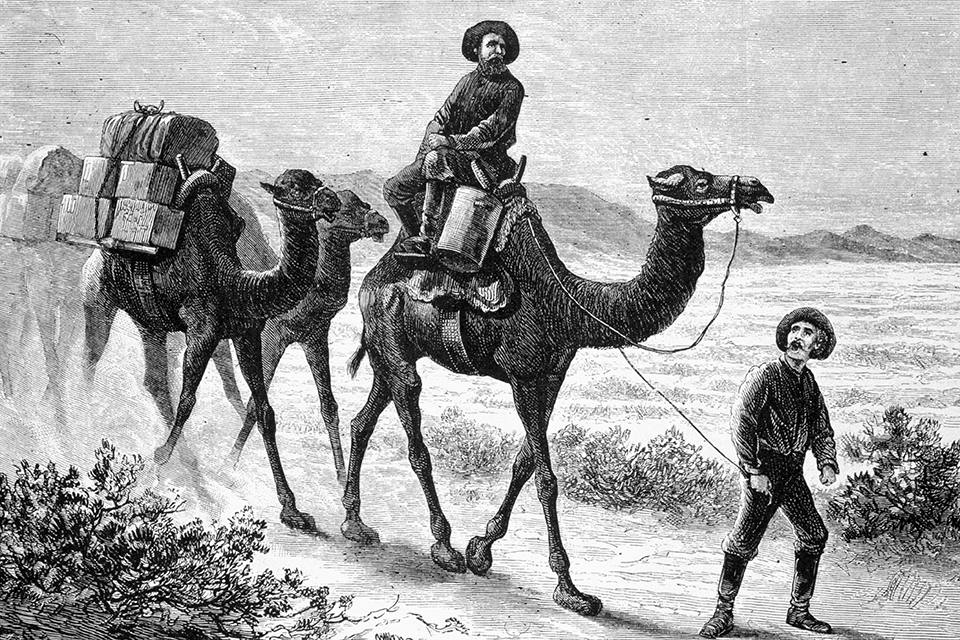

At first, incoming Secretary of War Floyd seemed eager to put the fledgling Camel Corps to work. A four-month debut project—surveying for construction of a federal road north from El Paso to Fort Yuma, then west to the Colorado River, an 800-mile trek ending at the California border—began that June. Employing 25 Arabians from Camp Verde, each toting roughly 700 lb., and 75 mules, each carrying about 175 lb., Beale led the expedition through country “where everything ahead is dim, uncertain or unknown, except the dangers.” At one point, Beale, riding a large white dromedary stallion named Seid, galloped off, sheik-like, on a 27-mile scouting foray. “The best horse or mule in our camp,” he marveled, “could not have performed the same journey in twice the time.”

The party reached California on October 17 but Beale wasn’t quite done. After sending a 22-animal caravan to Fort Tejon, an outpost adjoining what is now California’s Los Padres National Forest, Beale saddled Seid while Hadji Ali—his name Americanized as “Hi-Jolly” —saddled Tuile. Accompanied by horsemen, the two riders navigated their Arabians across more than 200 miles of barren terrain to reach El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de Porciúncula. The animals’ arrival at what is now Los Angeles stirred excitement. Camels had reached the American West.

Citing Beale’s enthusiasm, Floyd unsuccessfully urged Congress to buy 1,000 more camels, even though Lloyd and Jesup scarcely were able to employ—or maintain—their existing herd. One Arizona cavalry captain’s request to use Arabians to chase marauding Indians did get Jesup’s endorsement, but Lloyd turned down the overture. At Camp Verde, meanwhile, Innis Palmer pleaded for funds to clothe his “nearly naked” foreign drovers. A major impediment was Department of Texas commander David E. Twiggs. “I know that no living animal can bear the pressure of 600 pounds and go through a campaign in our country,” Twiggs declared.

By now the West Coast Arabians had relocated to Camp Fitzgerald near Los Angeles. With little else to do, Hi-Jolly and George Caralambo—“Greek George” to all—gave camel rides to curious schoolchildren. Male camels began to scrap. During one particularly vicious fight, Tuile stepped on Seid’s head, killing the stallion.

Learning of the camels corralled down South, Newman S. Clarke, the California Department’s San Francisco-based commander, requested jurisdiction. Jesup agreed, but it was September 1860 before Clarke instituted a “camel express” resupply route, an erstwhile “Dromedary Line,” between Los Angeles and Fort Mohave, 300 miles northeast. Greek George inaugurated the run only to have his camel die en route. When Clarke died that October, the Dromedary Line ceased. Mules stayed the preferred beast of burden.

By now, civilian camels were reaching American shores. In October 1858, American steamship Thomas Watson, a known slaver, docked at Galveston, Texas. The owner of record, Mrs. M. J. Watson, declared her vessel was carrying 89 camels. She asked British Consul Arthur T. Lynn for the certification of health required of vessels leaving Galveston for British ports. Suspecting Watson was bound for Cuban slave ports, Lynn declined. During the ensuing dispute, Watson let the beasts go free. About half succumbed to disease or slaughter before she paid a local rancher to round up the survivors. He pastured them on the mainland but, when payments stopped, they too were set loose.

In July 1860, San Francisco merchant Otto Esche returned to San Francisco from China with 45 winter-hardened Bactrians. He quartered the animals in a tent on Bush Street, planning to auction them individually. When Esche’s $1,200-per-head asking price got no takers, he sold ten in a package deal to Julius Bandmann, who pastured them near Pacific Street with occasional thistle-grazing forays to the Presidio. Bandmann resold the beasts for service as pack animals working the Washoe silver mines in distant Esmeralda County, now part of Nevada. Esche, meanwhile, sold a British Columbia mining outfit two dozen animals for a total of $6,000. Employed until 1863 on the rugged Old Cariboo Road, the “Cariboo camels” eventually were set loose. At least one, said to have been mistaken by a hunter for a bear, was killed, butchered, and served as “grizzly steaks.” Some of the beasts meandered south to Idaho and Nevada.

By then, two dozen Military Camel Corps Arabians had completed their final meaningful job, a midsummer 1859 topographical survey of the Big Bend region in southwest Texas. As Wayne and Beale had, expedition leader Second Lieutenant Edward L. Hartz extolled the animals. “The patience, endurance and steadiness which characterize the performance of the camels during this march,” Hartz wrote in his journal, “is beyond praise.”

Civil war undid the Camel Corps. When Texas seceded on January 28, 1861, former U.S. Army camels were neglected and abused. Some creatures delivered rural mail; one hauled a Confederate general’s baggage. Another, Old Douglas, served with the 43rd Mississippi Infantry; he was killed at Vicksburg. Three camels escaped to federal lines in Arkansas, they were auctioned in St. Louis. When peace was declared, Camp Verde’s 66 surviving camels were sold at auction for just $330 to Bethel Coopwood, a Confederate cavalryman who had fought in Arizona and New Mexico. Selling the Ringling Brothers Circus five animals, Coopwood employed the rest of the herd carrying freight between Laredo, Texas, and Mexico City. That business soon failed.

The army also auctioned its California camels. Caravanned amid great curiosity up the coast to San Francisco in 1863, all three dozen Arabians—including Tuile, now “Old Tule” and 35 years old—fetched $1,945 from Samuel McLaughlin. He sold a few to a small circus, sent others to silver mines in Nevada, and staged a few “Great Dromedary Races.”

In ensuing decades, remants of America’s camel experiment made occasional news. Edward Beale kept several at his ranch near El Tejon, California, training a pair to pull a sulky on 100-mile trips to Los Angeles. In advance of July 4, 1876, animals that had passed through Otto Esche’s and Julius Bandmann’s hands climbed 9,000-foot Mount Davidson, Nevada, hauling firewood to fuel a centennial bonfire visible “from all parts of the Washoe Valley.”

By mid-1857, all but three Levantine drovers had returned to their homelands. As late as the 1885-1886 cavalry campaign against the Apache war chief Geronimo, Hadji Ali, now a naturalized citizen named Philip Tedro, skinned mules for the army. He married a Tucson woman and fathered two daughters but died impoverished and alone in 1902.

Greek George, too, became a citizen. Known as George Allen, he lived for a time near what is now Hollywood’s Santa Monica Boulevard. Speaking only Spanish and recognizable by a “Homeric” and seemingly “bulletproof” thatch of beard and hair, he died in 1913.

The Turkish-born Elías was to exert the most significant impact. Moving to Sonora, Mexico, where he wed a Yaqui Indian woman, Elías operated a ranch and fathered Plutarcho Elías Calles. Nicknamed El Turco, Calles served as a populist Mexican president 1924-1928.

By the mid-1880s, American interest in camels as beasts of burden had run out. Cowboys and Native Americans who encountered feral camels were more inclined to kill than domesticate them. Accordingly, the 1883 sightings of Arizona’s Red Ghost sparked the sort of wonder later sparked by UFOs. The Arizona mystery resolved itself in stages over the next decade. A month after the water carrier’s death, a rancher claiming to have seen the “Red Ghost” described a shaggy red-hued camel carrying a human figure. Seeing the same apparition weeks later, prospectors shot at it; the animal fled, shaking loose a human skull with bits of flesh and hair attached. Finally, in 1893, a rancher saw the Red Ghost consuming his turnip patch, grabbed a rifle, and killed the beast; inspection revealed that knotted rawhide strips, some cutting into the dead animal’s hide, had been securing remnants of a corpse. “The only question,” noted the Mohave County Miner, “is whether the man was tied on him for revenge or merely as an ugly piece of humor by someone who had a camel and a corpse for which he had no use.”

Over ensuing decades, camel sightings persisted but gradually dwindled. “Old Topsy,” last documented descendant of the original Camel Military Corps, died in 1934. “Attendants at Griffith Park,” the Oakland Tribune reported, “destroyed her after she became crippled with paralysis.”