Among single-shot musket-bearing troops of 17th century Europe, cold steel remained more effective than lead in close-quarters clashes. As early as 1611 put-upon musketeers were jamming pocket daggers into the muzzles of their guns. This makeshift weapon of last resort evolved into the plug bayonet, its name likely derived from the cutlery center of Bayonne, France. The first known mention of its military application appears in the memoirs of Chevalier Jacques de Chastenet, seigneur de Puységur, who describes the French use of crude, foot-long plug bayonets during the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48). Not until 1671, however, did General Jean Martinet standardize plug bayonets for his fusilier regiment. English dragoons adopted the weapon a year later.

By then the plug bayonet had proved a mixed blessing, as it was difficult to remove from the muzzle should an infantryman need to reload his musket and resume firing. At the July 1689 Battle of Killicrankie, Scottish Maj. Gen. Hugh Mackay lost half of his 4,000-man infantry to a Highlander charge when his troops failed to fix their plug bayonets in time. An early solution was the ring bayonet, offset from the barrel to allow firing with the bayonet fixed in place. Mackay re-equipped his surviving infantrymen with this variation.

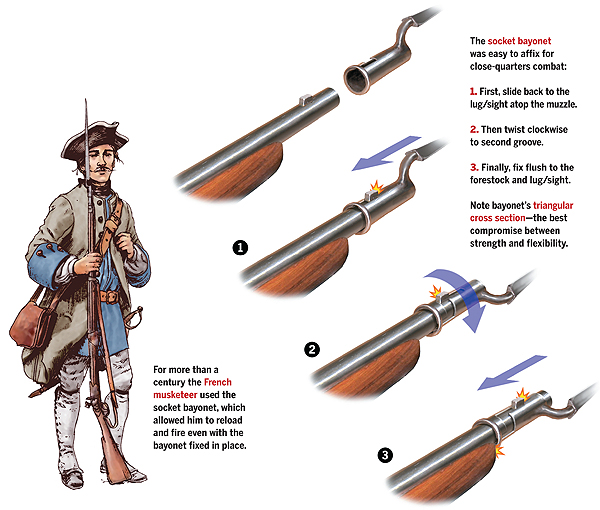

In 1703 the French army chose the socket bayonet for its infantry. Secured to a lug/sight atop the muzzle by a zigzag slot, a butterfly screw or a spring-loaded catch, socket bayonets predominated on battlefields through the 1840s. Over the next half century, sword or knife bayonets eclipsed the socket type, as soldiers could wield such bayonets independent of their other weapons.