‘A southeast Alaska evening in early July, bathed in gentle light, is usually calm, but the quick-stepping march of the armed men unsettled the air like the unforeseen approach of a storm’

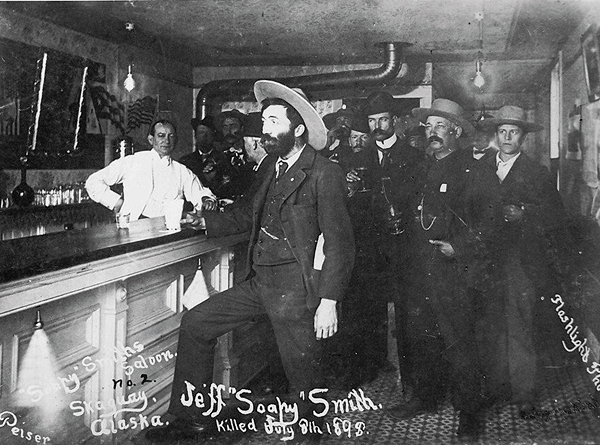

At about 9 p.m. on Friday, July 8, 1898, with the sun still shining bright in summertime Skagway, District of Alaska, newspaper- man William Saportas entered Jeff Smith’s Parlor and slipped a note to the owner of that booming saloon:

THE CROWD IS ANGRY, IF YOU WANT TO DO ANYTHING DO IT QUICK. S.

Jeff Smith agreed—quick action was needed. He, the “uncrowned king of Skagway,” knew that the Skagway Citizens’ Committee, which opposed him, had called a town meeting that evening. He had been drinking steadily but did not wait to sober up. Stuffing the note into a pocket (where it was later found), he grabbed a Winchester .44-40 rifle and headed out the door.

The slight figure in dark clothes and a tan hat was familiar on commercial Holly Street (present-day 6th Avenue), except on this evening Jeff Smith was not on a boardwalk but in the street itself, moving at a quick pace with repeater in hand. Over the years only a few had bested “Soapy” Smith, as he was known throughout the West, and certainly no committee quickly formed by his enemies would claim that distinction. Facing down angry men was risky, but the well-known confidence man had done it many times. So once again Smith was ready to back the hand that had been dealt him. Only this time everything would be different. Another victory was not in the cards; this time Soapy would be a victim. Turning left on Runnals (now State Street), Smith adjusted his pace for the six-block walk to Skagway Bay and the entrance to the Juneau Co. wharf. About a dozen yards behind Smith, six or seven of his men hurried to keep up. A southeast Alaska evening in early July, bathed in gentle light, is usually calm, but the quick-stepping march of the armed men unsettled the air like the unforeseen approach of a storm.

Actually, the change in atmosphere had been building for days among Skagway’s residents, bunco men, passers-through, real-estate grifters, railroad men and vigilantes. Three days before a Soap Gang member had come to Smith, who had been the most infamous con man in Colorado before coming to Alaska, and reported that because he felt an ominous change on the streets, he would be leaving for Seattle. Jeff’s reply was curt: “You ain’t got no nerve.”

That was something Soapy Smith had in spades. Back in January he had displayed his nerve at a raucous meeting in Union Church. John Fay, a bartender at the People’s Theater, had just shot and killed unarmed patron Andy McGrath and Deputy U.S. Marshal James M. Rowan. Gunning down two men was bad enough, but one of them was a lawman whose wife had given birth to their first child only hours before the killing. Outraged residents were all for hanging Fay. Only one man stepped forward on behalf of Fay—Soapy Smith. As the underworld boss he was obligated to protect those who supported his empire. Smith called for calm, rationality and preservation of law and order, threatening to shoot anyone who tried to carry out a lynching. His appeal prevailed. Fay was sequestered and then quickly sent to Sitka to await trial. Now, after receiving the newspaperman’s note, Smith would again appeal for calm, rationality, law and order—and vow to shoot anyone who threatened it.

The flash point this time was a con game gone badly awry. Smith’s Soap Gang had robbed a returning miner of his poke containing gold dust worth $2,600 (some $70,000 in inflation-adjusted dollars). Usually a victim would wager in a game and lose, think he bore responsibility for the loss, at least in part, and go away quietly. But this time the victim, John Stewart, had not wagered. Stewart claimed that in an alley beside Jeff Smith’s Parlor one of Soapy’s men had grabbed his gold and run. When Deputy U.S. Marshal Sylvester S. Taylor (on the Smith payroll) gave him the runaround, Stewart complained to everyone he met, gained sympathy throughout the town and roused anger at the usual suspects—Jeff Smith and his Soap Gang. For Smith the scene was familiar—a citizen crying foul after losing a “fair wager” and causing trouble that Soapy would straighten out through pure force of nerve. The year before, while preparing to come north to Skagway (spelled Skaguay at the time), Smith had said: “This is my last opportunity to make a big haul. Alaska is the last West. I know the character of the people I shall meet there, and I know that I am bound to succeed with them.” He had for the most part succeeded up north and now had a lot at stake in his Skagway operations. He did realize even his good luck could change, though, “when the very devil is in the run of the cards.” In the cards for Soapy was personal tragedy, but the truth about what transpired in his final fight eluded historians for more than a century.

The 20-foot-wide Juneau Co. wharf, one of four in Skagway, crossed the mud and gravel beach at a height of 6 to 10 feet and extended nearly a half-mile into the bay. At its far end was a warehouse over water deep enough for ships at low tide. Jeff Smith came striding up to the wharf sometime between 9 and 9:30 p.m. on July 8, holding his rifle almost casually over his right shoulder, muzzle pointing up and to the rear. A little way from the entrance, he saw four men who, according to The Skaguay News, were “to guard the approach to the dock, in order that no objectionable characters might be admitted to disturb the deliberation of the meeting.” Those objectionable characters were, of course, Soapy and his Soap Gang.

One guard, John Landers, stood talking with another man. About 60 feet down the wharf, against the west railing, guards Josias M. “Si” Tanner and Jesse Murphy stood near one another. A little farther on the fourth guard, Frank H. Reid stood alone. A crowd of 200 men had gathered another 200 feet down the wharf. Three of the guards were unarmed, but Reid carried a .38 Smith & Wesson, “an ancient gun,” as was later reported, that Reid “had used in the rip-roaring days of the West and which he considered the best gun in Skagway.”

When Smith reached the entrance, he stopped, and his followers caught up to him. Smith likely told his men not to go any farther, as he continued alone down the center of the wharf. Witnesses said he advanced without hesitation, cursing. Approaching Landers and the unidentified man, Soapy ordered the pair off the wharf. They obeyed, jumping over the side to the beach some 6 feet below. Smith then passed Tanner and Murphy without addressing them; they did not try to stop him. As Smith advanced, Reid called out to him: “Halt! You can’t go down there.” Exactly what happened next remains uncertain.

The generally accepted version follows. Smith walked up to within arm’s length of Reid, and their words grew heated. Smith suddenly swung the rifle off his shoulder at Reid, apparently intending to stun him with a blow to the head. Using one’s gun as a club was not uncommon in the frontier West. If that didn’t work out, bullets usually followed. Reid deflected the blow with his arm, grabbed the barrel and pressed it down. The men were then face-to-face, inches apart, jostling and swearing. As Reid wrangled the rifle barrel in his left hand, with his right he drew and aimed his revolver at Smith. At that point Soapy is said to have shouted, “My God, don’t shoot!” Reid, however, pulled the trigger. The result was a resounding click. The hammer had fallen on a faulty cartridge. As Reid moved to shoot again, Smith jerked his rifle free.

The adversaries opened fire on one another in nearly perfect unison. Some described the sound as being like a single shot, and one witness said both guns spat flame simultaneously. More shots followed in quick succession, and both men fell to the wharf. Reid had been struck twice—in one leg and in the lower abdomen and groin—and had fallen face forward. Three bullets hit Smith: one grazed an arm, another penetrated a thigh, and the last pierced his heart, killing him instantly. Smith’s followers charged in, weapons drawn, then stopped, backed away and fled as a swarm of anti-Smith men came at them.

Members of the citizens’ committee put the severely wounded Reid on a makeshift stretcher and rushed him to a doctor. The next morning, Saturday, July 9, Reid was taken to Bishop Rowe Hospital, and as the days passed, hope grew that he might recover.

Smith lay dead on the wharf for some hours. Charles Augustus Sehlbrede, the recently appointed U.S. commissioner for the district, ordered the body guarded and then later removed to Ed Peoples’ undertaking parlor, which served as the town morgue. On the morning of the 10th Sehlbrede appointed a coroner’s jury and ordered an autopsy. On Monday, July 11, at about 3 p.m., the Rev. John A. Sinclair conducted a funeral ceremony. “In the dreary morgue,” Sinclair wrote in his diary, “…I closed the chapter of this poor desperado’s career.” Just eight people accompanied Smith’s remains to the cemetery.

Reid did not recover. Bedridden in agony for 12 days, he died on July 20. His funeral the next day was the largest Skagway had ever witnessed. A photograph shows a closed coffin in Union Church, draped with a flag and heaped at the base with flowers. The crowded scene at the cemetery, Skagway’s Morning Alaskan reported, was “a pageant imposing and impressive.” Reid boasted a better cemetery plot than his adversary. Smith was placed in a rocky section that, according to Sinclair, allowed for “a meager foot of covering for his coffin.” Soapy’s marker inscription read JEFFERSON/R. SMITH/AGE 38/DIED JULY 8/1898. His 38th birthday, though, would not be for another four months.

Reid’s marker was of the same design as Smith’s, a wooden board rounded at the top and painted white. The black lettering read F.H. REID/DIED/JULY 19, 1898/AGE. As Reid’s age was not yet known, the space was left blank. Funds were collected for a stone monument to replace the marker, and in 1899 workers installed a tall granite piece at a cost of $450. The monument reads: FRANK H. REID/DIED/JULY 20, 1898/AGED/54 YEARS/HE GAVE HIS LIFE FOR/THE HONOR OF SKAGWAY.

Reid might have given his life to honor Skagway, but mounting evidence indicates he did not actually kill the man implied to have dishonored Skagway. While Reid did shoot it out with Soapy Smith, a closer look at the shooting details and the statements of witnesses strongly suggest not only that another man fatally shot Soapy Smith at the tail end of the fight, but also that town leaders covered up the facts of the killing.

The most likely scenario leading to Soapy Smith’s death follows. Jesse Murphy, a carpenter with the White Pass & Yukon Railway and one of the four guards at the wharf on July 8, was more heavily involved in the fight than the history books say. As mentioned, Murphy was standing near fellow guard Si Tanner when Reid and Smith argued and opened fire. But when the two adversaries fell to the wharf at the same time, both shooters (contrary to almost all accounts), not just Reid, were still alive. Smith’s followers then charged with weapons drawn. Murphy and Tanner, who had let Soapy pass them uncontested, saw the men coming. Murphy reacted. He ran to the wounded Smith, pried the rifle from the prone man’s hands and turned the weapon on Soapy. At that point Jeff Smith uttered his last words, “My God, don’t shoot!” But Murphy fired anyway, finishing the job Reid had started.

No witness had a clearer view of what happened, besides Murphy, than Tanner, and what he saw is documented. The night of the shootout, Commissioner Sehlbrede appointed Tanner a deputy U.S. marshal, and in that capacity Tanner sent news of the shootout to Superintendent Sam Steele of the North-West Mounted Police. Tanner’s original message is not known to exist, but Steele documented it. On July 11, 1898, in his monthly report, Steele wrote: “According to the information I received from the deputy marshal, a man named Murphy is credited with the killing of Smith, and not Frank Reid, as reported in the newspaper.” In a follow-up report, Steele confirmed Tanner’s account: “On the 11th instant I informed you of a shooting affray which occurred in Skaguay.…Soapy Smith was shot and killed from his own gun by a man named Murphy. Mr. Reed [sic] (who received two bullets from Smith’s gun) died a few days afterwards.”

The reports from this highly credible source are persuasive evidence. And there is more. After the fight Murphy insisted he had killed Smith. Murphy’s claim is documented in a letter from Skagway’s Dr. C.W. Cornelius to a Dr. H.R Littlefield, who, in turn, shared the letter’s contents with a newspaper in Portland, Ore., Cornelius’ hometown. “The shooting, Dr. Cornelius says, is the best thing that ever happened to Skagway next to the new railroad,” reported the Morning Oregonian on July 19, 1898. “Dr. Cornelius performed the autopsy on Smith’s body for the coroner’s jury. A man named Murphy claimed after the first autopsy that it was his bullet that killed the gambler, and it was necessary to perform a second [autopsy] to determine that Reed’s [sic] bullet did the work.”

If a second autopsy took place, Cornelius likely performed it immediately following the first. In its July 15 edition The Skaguay News reported how the jury “worked through the day…until nearly half past 4” to sort out who would go down on record as having fired the bullet that killed Soapy Smith.

Other evidence shows that Reid did not kill Smith and that only Murphy could have. Tanner reported that after the shooting he immediately retrieved Reid’s revolver, and that upon opening it, he saw three shells, two expended and one not. Smith’s body had three wounds—one a graze along the forearm from a bullet and two entry wounds from bullets, one through the leg and one through the heart. Reid could have fired just two bullets. The only other firearm belonged to Smith, and Murphy himself claimed to have picked up Smith’s rifle, aimed it at Soapy and fired.

Why was Reid, and not Murphy, said to be the one who killed Soapy Smith? One explanation is that those who had just taken control of Skagway, namely the leaders of the vigilante Skagway Citizens’ Committee, felt the need to protect their power. When Captain Richard Thompson Yeatman, a U.S. Army district commander in Dyea, across the bay, heard of the wharf fight and of the threat of further violence in Skagway, he offered military assistance. Commissioner Sehlbrede declined it, saying the town was under sufficient civilian control. The captain must have had doubts, however, as in the following hours and days he kept in telephone contact with Sehlbrede and let it be known that if civil control wavered, he would put Skagway under martial law.

Yeatman indeed might have declared martial law, had he known the facts—that Soapy Smith had been prone and wounded at the time he was shot (tantamount to murder), that no suspects had been arrested, and that the leaders in Skagway had covered up the circumstances of the killing. They seemingly did not want authorities to arrest Murphy, the actual killer. Had authorities done so and then released Murphy, those who posted his bond might face suspicion of protecting him—perhaps even of hiring him to kill Smith.

The official story, as far as Sehlbrede and the citizens’ committee were concerned, was that Reid had killed Smith in a face-to-face fight on the wharf, and that no one had intervened. Better to allow the gravely wounded Reid to be the hero than to credit the killing to Murphy, which might have prompted a murder investigation. Had officials at the coroner’s inquest told Murphy to go along with the cover-up or risk prosecution for his actions that night?

Samuel Graves, president of the White Pass & Yukon in 1898, claimed in his 1908 book On the White Pass Payroll that he had witnessed the fight on the wharf. He wrote that one of the “entrance keepers” that night was “a little Irishman named Murphy who worked for us.” Graves followed with this vivid account:

When his [Smith’s] guards saw “Soapy” fall, they gave a ferocious yell and drew their “guns” (as they call their heavy revolvers) and sprang forward for vengeance on the unarmed crowd.…But the little Irishman was the right man in the right place and rose to the emergency, as our White Pass men have a way of doing. ‘Begob, Sorr,’ he said to me an hour later, ‘I had nawthing but a pencil whin I saw thim tigers making jumps for me.’ But he had his quick wits, and like a flash he had snatched ‘Soapy’s’ Winchester from the dead man’s hands, and the leading ‘Tiger’ saw Murphy’s eye gazing at him along the sights.

While Graves’ account places Smith’s Winchester in Murphy’s hands, cowing Soapy’s henchmen, there is no mention of Murphy shooting Smith. According to Graves, Reid and Smith had “fired together,” falling “in a confused heap on the planking of the wharf, ‘Soapy’ of course stone dead.” Had he censored his account of the killing for Murphy’s sake?

Why would Murphy choose to finish off Smith? Perhaps he thought that was his job, or that he was doing a good deed. Though wounded, Smith might have had the strength to lever his Winchester or to direct his men to open fire on Murphy and Tanner. Witnessing the murder of their boss by Murphy may have had a chilling effect on Smith’s men, halting their advance. “They’ve got Soapy, and they’ll get you next!” Tanner cried out (by Tanner’s own account to Alaskan historian Clarence Andrews). The approach of the crowd on the wharf, described by Graves as “a bloodthirsty pack of wolves,” was the impetus for Smith’s followers to bolt.

Murder was indeed in the air, and Soapy’s men ran for their lives. The citizens’ committee organized a manhunt, which few members of the Soap Gang managed to escape. The vigilantes held and questioned those they caught. They sent the three men suspected of robbing John Stewart to Sitka for trial and eventual imprisonment. Other Smith associates escaped conviction, but the vigilantes banished them from Skagway.

The coroner’s jury found that Reid had killed in self-defense, a finding that made, as a Morning Alaskan headline read, REID THE HERO OF THE HOUR. So the story has been told for 100 years. Now, however, with the new evidence that has come to light, the official story has changed. The account thought best for Skagway at the time—to keep it from martial law and under merchant, real estate and railroad control—kept hidden what had happened during the 10 seconds in which Jesse Murphy chambered a round into Soapy Smith’s rifle, heard the injured man cry out, “My God, don’t shoot!” and fired. A finding of murder would not have bestowed honor on Skagway. Neither, however, has an untrue story intentionally told to conceal a murder. William Shakespeare wrote, “Truth will come to light; murder cannot be hid long.” In the case of Soapy Smith it took about a century, but indeed truth has come to light.

Jeff Smith, a great-grandson of Soapy Smith, adapted this article from his biography Alias Soapy Smith: The Life and Death of a Scoundrel (2009), which is suggested for further reading. Also visit Jeff Smith’s website and blog. For another perspective see Catherine Holder Spude’s 2012 book “That Fiend in Hell”: Soapy Smith in Legend (see review). Spude argues that Soapy was just a petty criminal , but like Jeff Smith she challenges the traditional account of Soapy’s death.