A stand-off between sailors and captain on a lumber transport helped change seamen’s legal status

On the afternoon of June 11, 1895, the four-masted barkentine Arago was approaching the bar at the mouth of the Columbia River. Sailors reefed the ship’s foresails while others secured a hawser that had been cast across from the tugboat that was idling nearby. Once the heavy line was aboard, the tugboat crew engaged their vessel’s propeller, and, with black coal smoke boiling from the tug’s stubby stack, towed the 176-foot barkentine upriver to the waterfront mill in Knappton, Washington. Captain Frank Perry and his crew intended to spend the rest of June in Knappton, stacking freshly sawn lumber in Arago’s holds. The freight was headed for Valparaiso, Chile, 7,000 miles south. These voyages demanded sturdy vessels and happy crews to battle the ferocious winds, savage weather, and a reef-studded shore that ate ships. Arago’s crew was far from happy.

That dissatisfaction would precipitate a constitutional crisis and force Americans to reconsider maritime laws that limited a seaman’s rights. Although the states had ratified the 13th Amendment, ending slavery, sailors still were laboring under U.S. laws adopted from ancient British precedent that shackled seamen to their ships. When four sailors from Arago tried to desert, they were arrested, jailed, and ultimately returned to their ship, whereupon they were charged with desertion and mutiny. The case, which went t0 the U.S. Supreme Court, showed that not all workers in the United States had escaped the bonds of indentured servitude. Legislators, responding to public outrage and effective pressure from union leader Andrew Furuseth, crafted new laws to address this inequity, freeing sailors from their legal chains.

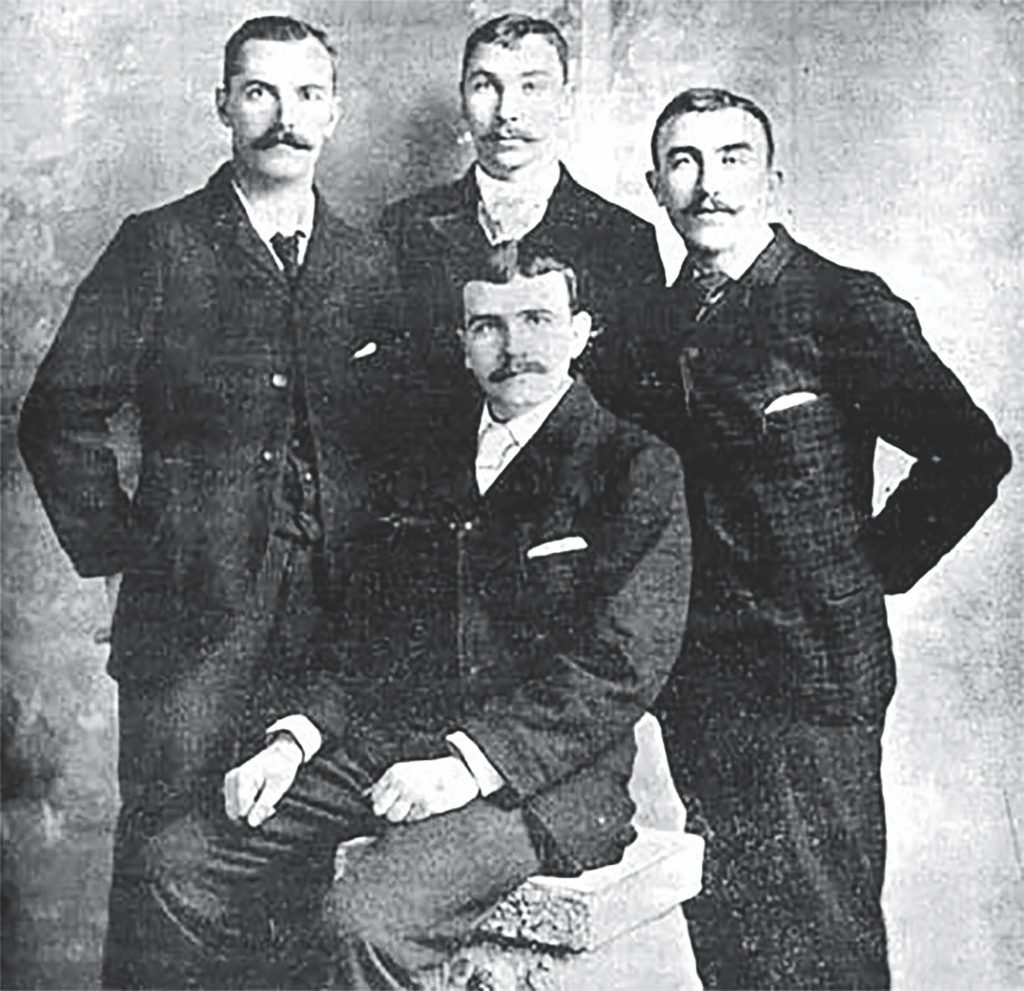

The crew tied Arago alongside the Simpson Lumber Mill in Knappton, five miles across the river from Astoria, Oregon. Night arrived. As an ebb tide chuckled through the mill wharf pilings, four crewmen—Robert Robertson, John Bradley, Philip Olsen, and Morris Hansen—slipped ashore and vanished. The four had not enjoyed the trip from San Francisco. They claimed that Captain Perry was a harsh taskmaster, a quarterdeck tyrant, and they had no intention of sailing with him to Chile. “The captain felt sure that he had us,” wrote Robert Robertson in a letter home. “On the trip he fed us on salt horse and bulldozed us. We went to him and told him that since we did not suit him, he had better pay us what was coming to us. This he refused to do, so we left him and our money at the first opportunity.” Robertson cited food quality—“salt horse” was meat, usually beef or pork, preserved in salt and stored in large casks—but the desertion probably traced to a steady onboard diet of unnecessary bullying and intimidation. “Bulldozing,” a slave-trade legacy, originally had referred to a whipping harsh enough to severely injure or even kill—a “dose” of discipline suitable for a bull. In the late 1800s that meaning expanded to include the hazing, harassment, and intimidation that a master was free to heap upon slaves or a captain upon sailors who could not fight back.

The four unhappy Arago crewmen decided to run. Since towns around the Columbia River’s mouth lacked overland connections to the interior, the four crossed to Astoria, Oregon, hoping to find a ship that would bear them away. When the men were reported missing, Captain Perry alerted the Astoria authorities. Deputy U. S. Marshal Richard Stuart had no difficulty apprehending the Arago deserters.

The next morning, United States Commissioner Clifton R. Thompson listened to the runaways’ side, but when the four admitted to having signed shipping articles—employment contracts binding on signatories until a vessel reached its final destination—Thompson remanded them to the Astoria jail, there to remain until Arago was ready to cast off.

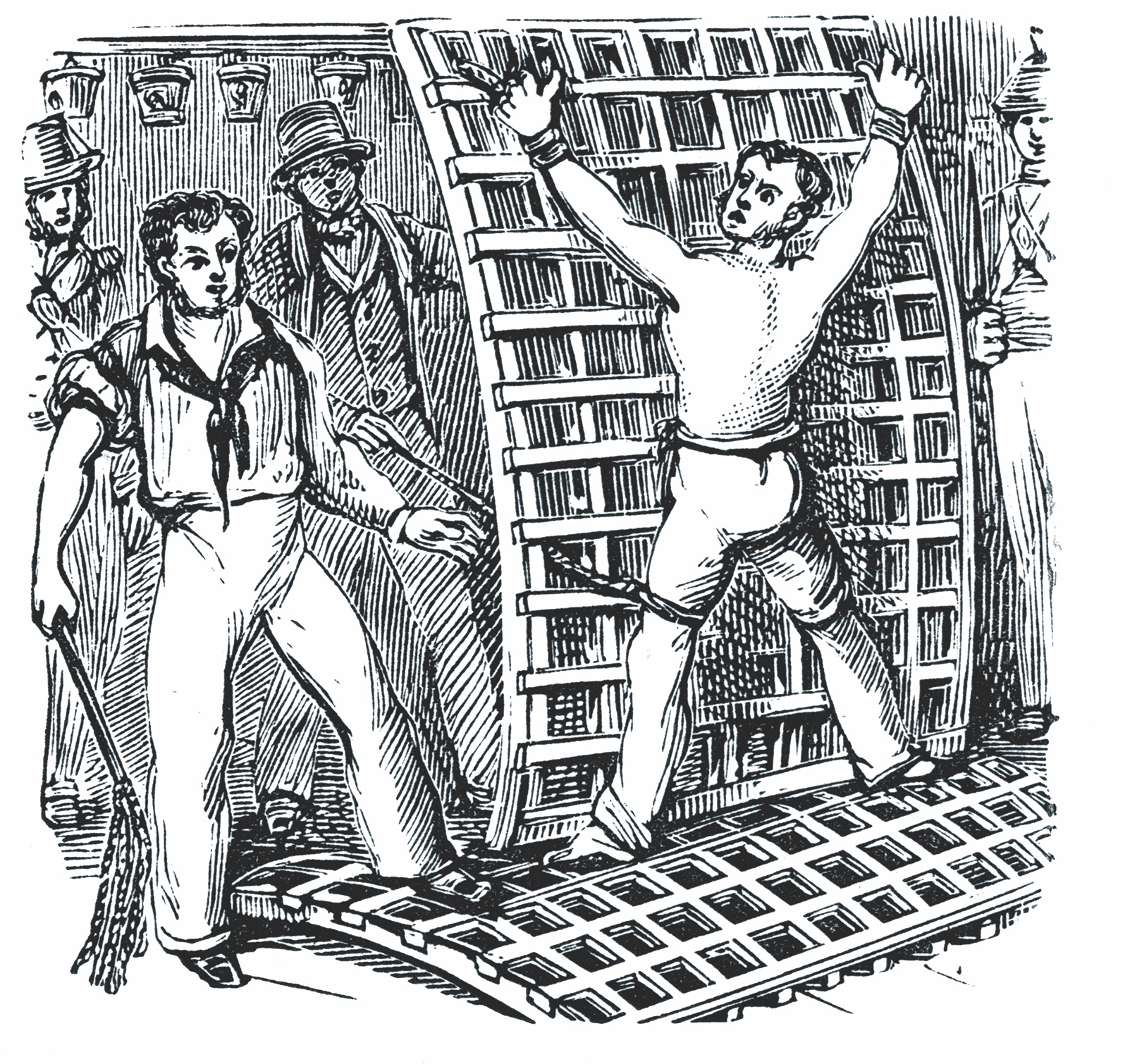

Land-based workers could escape brutal treatment by quitting their jobs. A scrappy logger might take a poke at a hard-driving foreman with little fear of consequences. Not so a sailor, who was constrained by his trade’s unique laws and traditions. Centuries-old regulations governed life afloat and denied seamen rights that were ubiquitous ashore. The right to act in one’s self-defense, for example, ended at the coastline. Sailors were not permitted to fight back against superiors, even when assaulted. A captain could strike a seaman, but a seaman who raised a fist in self-defense stood liable to be charged with mutiny. The Coast Seamen’s Journal, the weekly newspaper of the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific, highlighted this inequity in the “Red Record,” an ongoing series documenting abuse.

For example, aboard the vessel Reaper: “Second mate Gerdes beat a seaman, Smith; knocked him down and kicked him nearly to death. Smith was confined to his bunk for ten days. Then he was compelled to come on deck and go aloft. A sudden lurch of the vessel threw him to the deck, and he was killed. It was reported Smith was too weak to hold on. Case brought before the Commissioner at Astoria and dismissed.”

Along with self-defense, the maritime code forbade running away. In 1790, the First Congress of the United States enacted laws that shackled a seaman to his vessel. Section 4598 of the Revised Statutes of the United States (1873-1874) stated that if a sailor signed a contract to perform a voyage and then left his ship “at any port or place,” that vessel’s master could have local police arrest the deserter. Jumping ship was a criminal offense. The law enjoined local authorities to commit the runaway sailor “to the house of correction or common jail of the city, town, or place, to remain there until the vessel shall be ready to proceed on her voyage.” Nineteenth-century legislation complicated and confused the matter. An 1872 federal law created shipping commissioners, officials who oversaw all matters related to the trade. This law confirmed the treatment of deserters, but a law passed in 1874 excluded ships sailing on the Great Lakes or between U. S. harbors from commission jurisdiction and appeared to nullify the laws against desertion for all except sailors on international voyages.

In 1890, trying to placate shipowners, Congress passed a law reinstating criminal charges if a deserter had signed his shipping articles in front of a Shipping Commissioner. The 1896 Maguire Act attempted to reassign certain freedoms to seamen, but few sailors aboard Arago understood which laws applied when the ship got to Knappton. Captain Perry, Commissioner Thompson, and Deputy Marshal Stuart believed themselves to have been acting correctly.

The four miscreants spent 16 days behind bars while Arago took on lumber. On June 29, the barkentine was ready to depart for Valparaiso. Marshal Stuart loaded the four seamen aboard the tug that was to assist the Arago across the bar. Once the tug and Arago reached midstream, Stuart released Robertson, Olsen, Hansen, and Bradley into Captain Perry’s custody. Perry ordered the quartet to “turn to,” meaning “Get to work.” The sailors sat on the deck and ignored his commands. Their detention had been illegal, they claimed, and they refused to work. Perry was furious. He placed the men in irons and locked them in Arago’s hold.

The quartet’s intransigence meant the rest of Arago’s crew had to stand extra watches as the ship headed south. Realizing that he couldn’t sail to Chile shorthanded, Perry decided to anchor at San Francisco, offload the troublemakers, and sign replacements. News of the rebellion had preceded the ship. As Arago approached the city on July 7, 1895, a large crowd gathered on the docks. The fatigued crew nearly went aground on the rocks of the South Channel, but a passing tug threw a line and guided the barkentine to an anchorage off Meiggs Wharf.

Captain Perry ran a police flag up the mast, signaling a request for assistance. Two officers of the San Francisco Harbor Police rowed out and took custody of the disgruntled sailors. Since the four had refused to obey his orders while under way, Captain Perry insisted on adding “mutiny on the high seas” to the charge of desertion.

The incident appeared on its face to be a mere shipboard squabble over working conditions, but some San Francisco newspaper reporters considered the dispute’s timing suspicious. Skeptics among the fourth estate wondered if the Sailor’s Union of the Pacific had staged the desertion in order to test the law in court. If that had been the case, the Arago episode would have just been one more battle in the ongoing war between shipowners and the union.

That conflict began when sailors first organized on March 5, 1885, in response to a drastic pay cut. A year later, shippers countered, forming the Shipowners’ Association, an anti-union alliance. A decade on, the owners were ascendant: whenever possible, they blackballed union sailors. The few union men who did win berths afloat were compelled to sign their shipping articles in the presence of a Shipping Commissioner. As more seamen acceded to the owners, membership in the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific declined to less than a quarter of its 1885 tally. Secretary Andrew Furuseth, the union’s leader, desperately needed to show the sailors that the union could improve their lot.

Questioned about Arago, Furuseth denied that the men had acted with premeditation, declaring them victims of the blatant injustice that dogged every man who earned his living afloat. There was no need to prearrange an incident, the union boss said—it could have happened at any time. The Sailors’ Union of the Pacific would stand with these men, working to secure justice for every sailor, he declared.

The union hired attorney Harry W. Hutton, who filed to have the charges against the four dismissed. After a preliminary hearing, U.S. Commissioner Edwin H. Heacock scotched Hutton’s motion. He set defendants’ bail at $50 apiece; when the men pleaded indigence, he ordered them into the Alameda County jail. Hoping to secure his clients’ release, Hutton filed a federal writ of habeas corpus claiming Marshal Stuart had illegally detained and returned the sailors to Arago. The shipping laws that made desertion a criminal offense violated the Thirteenth Amendment’s prohibition of involuntary servitude, the defense attorney said.

In fact, Hutton argued, Congress had no more right to punish sailors for leaving a ship than it had to punish any man who walked away from a job. An owner could sue a worker who failed to fulfill his contractual obligations, but he couldn’t have him arrested and jailed. Breach of contract was a civil, not a criminal matter. “If the sailors wanted to break their contracts, they had a right to do so,” Hutton said. “The law which says they cannot do so is an arbitrary one, and it deprives men of their liberty.”

The accused sailors, wrote the San Francisco Chronicle, “seek their liberty on the ground that they are imprisoned under an old English law, copied almost bodily into the Federal statutes in 1790, a law which it is alleged is contrary to the genius of American institutions and to the whole spirit of modern civilization.”

District Attorney Henry S. Foote countered that a marine contract differed substantially and significantly from one executed on land. To protect shipowners, legislators had to require sailors to fulfill their contracts, argued Foote. Absent this assurance, ships would be unable to operate. Sailors could quit at will, stranding vessels in remote ports and creating an economic hardship for masters and owners.

On July 30, Judge William W. Morrow denied a writ of habeas corpus, declaring that the recalcitrant sailors must stand trial for mutiny and desertion. San Francisco shipowners filled the courtroom gallery.

When “the court intimated that the men had been lawfully arrested and put on board the barkentine at Astoria,” the San Francisco Call wrote, “there was a sigh of relief from the merchants.” Sensible views had prevailed in the confrontation’s first round.

Harry Hutton appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The justices heard Robertson v. Baldwin on December 15, 1896. On January 25, 1897, voting 8-1, the justices confirmed the lower court’s ruling denying habeas corpus. Justice Henry Brown wrote for the majority, “The contract of a sailor has always been treated as an exceptional one, and involving to a certain extent the surrender of his personal liberty during the life of the contract.” The requirement that “seamen carry out the contracts contained in their shipping articles, are not in conflict with the Thirteenth Amendment forbidding slavery and involuntary servitude, and it cannot be open to doubt that the provision against involuntary servitude was never intended to apply to such contracts.”

Interpretation of the phrase “involuntary servitude,” argued Justice Brown, stood at the center of the issue. A slave was unwillingly forced into service; a sailor, like a soldier, entered service freely. Both sailors and soldiers chose to renounce certain rights when they joined an organization, whether a ship or an army, a voluntary decision not open to a slave.

For the sake of national security and safety at sea, it was essential that sailors and soldiers remain at their posts until released from duty by their superiors, Brown wrote. By their very nature, these vocations could not tolerate desertion. Where would a country be if a soldier fled the battle or a sailor refused to do his duty in a time of peril, the justice asked.

Finally, noted Brown, the maritime laws in question had long enjoyed the imprimatur of antiquity. Precedent stretched far back to the ancient constitutions governing the Mediterranean island nation of Rhodes. Laws conceived before the common era stipulated severe penalties for crewmen who deserted their ships. The entire history of maritime law argued against a sailor’s right to desert, Brown wrote.

The high court’s decision was a blow to the defendants as well as to the union cause. The Court affirmed the laws that denied sailors rights which were enjoyed by citizens ashore. Sailors could be abused, beaten, starved, and forced to work under horrific conditions. They could not jump ship, even when desertion did not imperil a vessel. According to the U.S. Supreme Court, a sailor signed away these rights any time that he initialed a set of sailing articles. “It is better to know that hereafter when a seaman signs articles to go on a voyage, he is a slave until the captain and shipowners have no more use for him,” wrote Robert Robertson, de facto leader of the Arago deserters. “Before this case was decided, the seamen were laboring under the delusion that they were entitled to the privileges of any other American citizen.”

The Supreme Court ruling in Robertson v. Baldwin catalyzed outrage in San Francisco. As shipowners celebrated, Furuseth and the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific plotted. When organizers asked the union to participate in San Francisco’s Fourth of July celebration, Furuseth declared, “The spectacle of a slave worshiping his chains would be less ludicrous than that of the American seamen celebrating Independence Day.”

Blocked by the Supreme Court, Furuseth realized that sailors’ only recourse was to lobby to change the law. In 1898, U.S. Representative James Maguire (D-California) and U.S. Senator Stephen White (D-California) introduced a bill to address federal maritime law’s more egregious aspects. This legislation, eventually known as the White Act, amended the U.S. Code to allow sailors to leave ships without obtaining a captain’s approval. Deserters could forfeit unpaid salary and their possessions, but no longer could captains use the police to drag runaways back to their ships. The White Act upheld the premise that a sailor could not strike an officer—a transgression that remained punishable by two years of imprisonment—but leveled the deck by outlawing corporal punishment. A captain could no longer strike or flog a crewman—any officer violating the prohibition risked a misdemeanor charge, punishable by three months to two years behind bars.

It is not clear what happened to the four sailors who precipitated these reforms. Robertson, Bradley, Olsen, and Hansen spent nine months in the Alameda County jail before being released on their own recognizance. The penalty for desertion at this time was 200 days in jail and the forfeiture of four days’ pay. After the Supreme Court rejected the sailors’ appeal for habeas corpus, the San Francisco Call noted that the men were to stand trial for their actions, but no subsequent reporting shows that trial taking place. Since the men had already spent more than 200 days in jail and would be credited with time served, the district attorney may have decided that prosecution was pointless. After their moment of notoriety, the four returned to the obscurity that cloaked the existences of so many transient seamen.

Besides leading to legislative reforms, the Arago case also taught two important lessons. Sailors learned the utility of public sympathy in the pursuit of an equitable working environment.

San Franciscans and people across the country pressured legislators to address the injustice highlighted by Robertson v. Baldwin. The cause advanced quickly when the winds of public opinion filled its sails.

Seamen also discovered the power of collective action—the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific, after years of declining enrollment, proved itself able to achieve results. As independent sailors returned to the union, it became more effective with management, and, by 1910, had grown into one of the largest and most powerful labor unions on the Pacific coast. Andrew Furuseth—still described in union annals as the “Abraham Lincoln of the sea”—welded a growing membership into a powerful coalition that achieved legislative reform, economic justice, and safer workplaces for those who risk their lives at sea.