When women appear in the story of the American West, they are usually dance hall girls, schoolmarms or hard-working no-nonsense wives and mothers. But every now and then, a woman like Elizabeth Bonduel McCourt shines through and spices up a frontier tale.

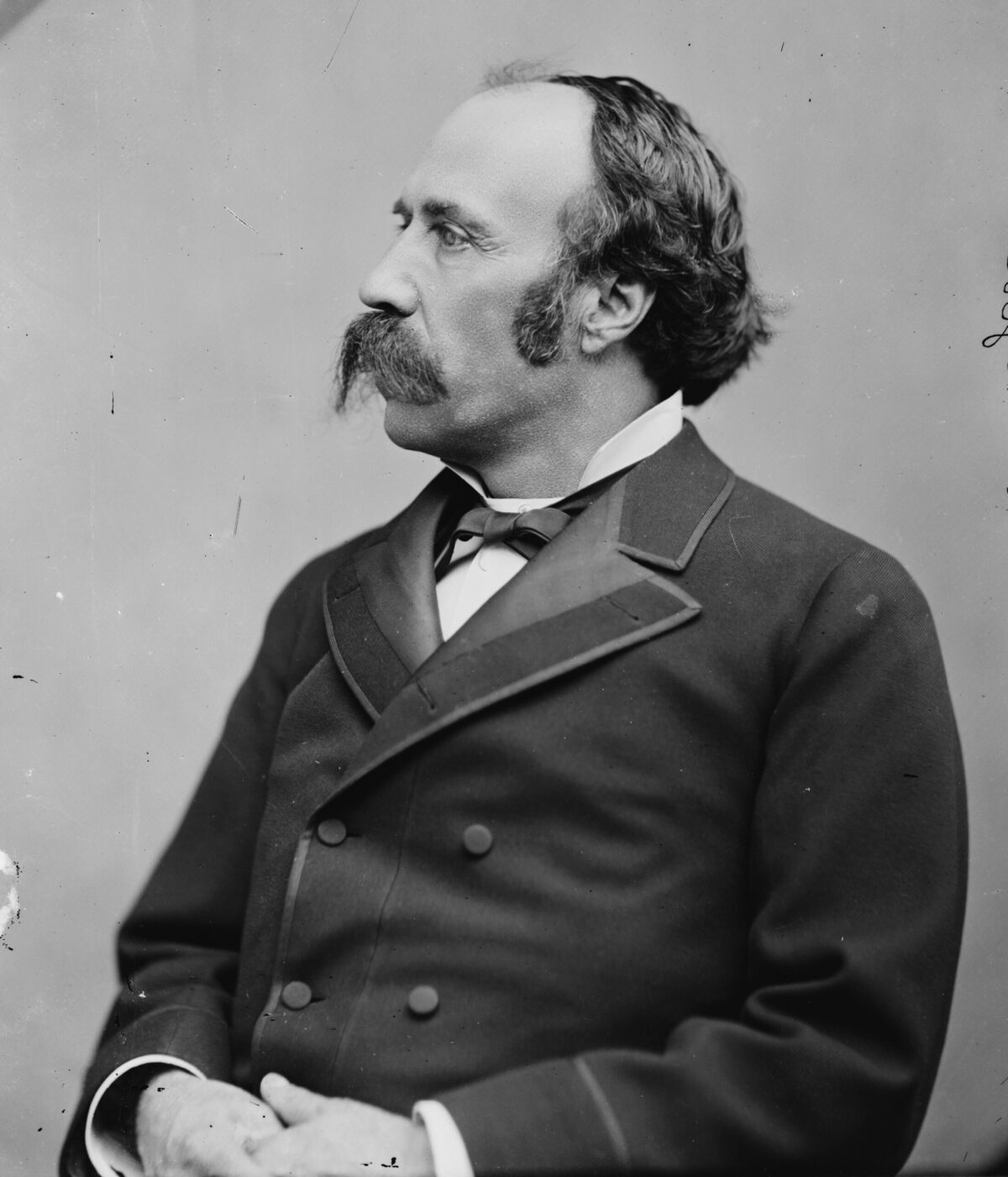

Born in Oshkosh, Wis., on October 7, 1854, “Lizzie,” as she was called by her family, blossomed into a striking blue-eyed blonde. In 1877 she married Harvey Doe Jr., and went west to the new state of Colorado, because Harvey’s father had half interest in a Central City mine. Young Harvey couldn’t make the mine work or otherwise make a buck, so his wife divorced him on grounds of nonsupport in 1880. She wasn’t single very long, though, for she had caught the eye of Horace Austin Warner Tabor, easily the wealthiest man around. He was known all over the Centennial State as “Haw,” and she was called “Baby Doe,” even after she became Mrs. Tabor—first in an 1882 private civil ceremony in St. Louis and then again on March 1, 1883, in Washington, D.C., where she wore a $90,000 diamond necklace in a ceremony attended by no less a person than President Chester Alan Arthur.

HAW AND HIS FIRST WIFE

Like President Arthur, Haw Tabor was born in Vermont. At age 25, in 1855 Tabor ventured to Kansas Territory, where he served on the “Free Soil” Legislature. He returned to New England briefly in 1857 to marry Augusta Pierce, and then he brought her back to Kansas to live on a farm. He didn’t show much in the way of ambition. It’s hard to say what Augusta saw in him, since he had no sense of humor or anything that could pass for a winning personality. In a word, Haw Tabor was dull. What’s more, his prospects seemed dim.

Augusta was no ball of fire either, but she was tough, determined and fiercely loyal to her husband, whom she prodded to take her and their baby son, Maxcy, farther west in 1859. Gold had been discovered in the Pike’s Peak area in extreme western Kansas Territory. Only trouble was, Haw didn’t have much more luck placer mining on the eastern slope of the Continental Divide than he had farming. Initially, Augusta brought in most of the family income by selling milk and baked goods and by nursing prospectors who had suffered accidents in the mountains. Meanwhile, the Tabors kept wandering from gulch to gulch in hopes of making a lucky strike.

Sometimes things did pan out for Haw, especially after the Tabors ventured to the area around the headwaters of the Arkansas River in 1860. He and his wife came up with enough money to build a house in Oro City that not only gave the family plenty of room but also allowed Augusta to take in boarders. The ground floor had space for a general store and a post office, along with a back room where Haw could indulge his passion for poker.

Oro City produced several millions in gold, but when the vein ran out several years later, it suddenly became a ghost town, leaving for the Tabors a post office with no mail, a general store with no customers and a boarding house with no paying guests. The Tabors themselves left for a time, but by 1868 they were back in Oro City, serving some die-hard prospectors. Haw liked being a merchant, and now that the professional gamblers had moved on, he was the best poker player around. He and Augusta weren’t getting rich, but they managed to eke out a comfortable existence.

ALL THAT GLITTERS IS NOT GOLD

Among the hangers-on were an old miner named “Uncle Billy” Stevens and his partner A.B. Wood, a geologist who in 1877 discovered a rich vein of silver in the lead carbonate beds above town. They kept it to themselves until they had staked out claims up and down the silver streak, but even when the news got out, the other old sourdoughs weren’t impressed. After all, it was gold that the prospectors were after. But once Wood sold his half interest in the claims to Marshall Field of Chicago for $40,000, it wasn’t long before California Gulch was booming again. Leadville, at about the same location as the original Oro City, was incorporated in January 1878. Augusta’s little boarding house was transformed into a four-room hotel, and the general store expanded to include a barroom. Haw was elected Leadville’s first mayor.

He moved his poker table out into the barroom as a more visible profit center, and after years of practice he was easily able to protect his enterprise from the most rapacious gamblers. Haw had a solid reputation for honesty, and he became the depository for prospectors who preferred not to take their valuables into the hills with them. As a storekeeper, he was also in a position to provide “grubstakes” for down-and-out miners on their way back into the wilds for another shot at fortune. In return for the former, Haw stood to keep everything left behind by prospectors who didn’t come back. In the case of the latter, a grubstake was worth a third of any riches a miner happened to find. It was a gamble either way, but so was mining, and Haw Tabor had had enough of that.

In the spring of 1878, one of Haw’s grubstakes changed not only his life but also the fortunes of Leadville. August Rische and George Hook had gone west to follow their trade as cobblers, and after several years of trying came to the conclusion that the West was no place for makers of boots and shoes. They decided to try their hand at mining, but worse than knowing nothing about it, they didn’t have the price of the food and tools they’d need to work a claim. It was so clear that they were doomed to failure that nobody was willing to stake them. No one, that is, except Haw Tabor, and even he had his doubts.

Almost as much to get rid of them as anything else, Haw agreed to let them have their grubstake. He told them to take what they needed, sign for it, and get out of his sight before he changed his mind. While his back was turned, they added a jug of whiskey to their bundle and quietly headed for the hills.

Every prospector in the history of the West had his own system for finding pay dirt. The majority were unscientific about it, but there is no recorded instance of any claim ever staked as casually as the one established by Rische and Hook. They simply walked out of town and stopped when they got tired, about a mile up the road. The hillside looked as good as any and better than most because it was covered with trees, which meant they wouldn’t have to work under the hot sun.

They made camp there and started digging, taking plenty of breaks to sip their whiskey. They stopped when the jug was empty, but it turned out they had dug deep enough. There was a vein of pure silver at the bottom of the hole. A government survey made later confirmed that they had found the only spot in the whole area where it was that close to the surface. If they had dug even a few feet farther away, they’d have missed it completely and probably gone back to shoemaking.

Their Little Pittsburg Mine yielded $20,000 a week, but Rische and Hook weren’t the only ones who were suddenly rich. Haw Tabor’s $60 investment in their grubstake made him their partner, and he earned $2 million from the strike in the first year alone without getting his hands dirty.

RISE OF THE SILVER KING

Tabor was at the center of the bonanza that followed, buying and selling interests in mines all over the area. In 1879 he purchased the Matchless Mine, which truly had no equal for several years to come. That November, he opened the Tabor Opera House to provide some culture for his wife and others. Many tried, but few succeeded in swindling him, and in a short time he had become the richest man in an area that was producing more than 300 tons of silver a year. He rewarded Augusta with an ornate mansion in Denver, and another just as grand in Leadville that included quarters for servants to assure Mrs. Tabor a life of ease.

Augusta became a recluse, but the same couldn’t be said for her husband. In the almost unbelievable decade of the 1880s, Haw Tabor blossomed. He became lieutenant governor of Colorado while continuing as Leadville’s mayor. Leadville, whose population would rise to at least 24,000 that decade, had become the wildest boomtown in the Wild West, filled with fortune hunters, gamblers, pickpockets, thieves and generic scoundrels. But it also attracted its share of solid citizens—schoolteachers and engineers, lumberjacks and carpenters, blacksmiths and smelter workers, lawyers and doctors, preachers and even a few shoemakers following in the footsteps of Rische and Hook.

In spite of the town’s thin veneer of gentility, lawlessness was epidemic in Leadville. In a single month in 1880, no less than 40 people were arrested for murder, and probably two or three times as many went unpunished by the inept police department. The citizens themselves attacked the problem with vigilante committees that exacted justice with a length of rope and a tall tree.

Most of the rich mine owners protected themselves with small private armies, but none was as impressive as Haw Tabor’s Highland Guard, a 64-man bodyguard outfitted in livery worthy of Bonnie Prince Charlie. They wore plaid kilts with daggers in their long red stockings; their Scottish bonnets topped off by white ostrich plumes that were held in place by buckles of pure silver.

Everyone in town was impressed except the desperadoes who winked and went on about their business. Haw responded with a second little army, the Tabor Light Cavalry, a 55-man unit dressed in fancy blue coats and shiny silver helmets. Tabor gave himself the title of general and personally led his men around town wearing a gold-trimmed jacket. The custom-made sword at his side was said to have cost him $50, an outlandish sum in those days. It didn’t have much effect on the state of lawlessness, but it made the mayor look good and that, after all, was the point.

Leadville had more than just law-and-order problems. The stagnant wages and long hours led to a miners’ strike in the spring of 1880 that caused Governor Frederick W. Pitkin to declare martial law and call out the state militia. Mining operations soon resumed, and there was still plenty of silver in the hills, but investors shied away from providing money to get it out of the ground. Businesses went sour. Still, two years into the town’s so-called depression, it produced a record $17 million worth of silver. Tabor, though, was one of the pillars of the community who decided to move elsewhere. By 1882 he was cutting quite a figure in Denver, which had become the state capital the year before.

HAW IN THE CAPITAL CITY

To announce his arrival in the big city, Haw Tabor built a six-story building of stone imported to the Rocky Mountains from Ohio. It was no sooner finished than he began work on a second building with wood imported from Japan, and architectural stone from Italy. He claimed to have designed both buildings himself, but he did rely on the professional advice of an architect who he sent to Paris and Rome for inspiration.

As he had done back in Leadville, Haw included space for offices and stores in his new buildings, but the second one had something very special—the Tabor Grand Opera House. It brought culture to Denver in the form of minstrel shows, melodramas, Gilbert and Sullivan operettas and, yes, grand opera. Every major touring theatrical and musical company made it a point to play the Tabor Grand.

Haw enjoyed having his name linked to the likes of stage performers such as Lily Langtree and Edwin Booth, but what he enjoyed even more was making money, and it was clear that he had a flair for it. He owned mines all over the Southwest as well as in Colorado, and he controlled 400 square miles of the country of Honduras. He also owned banks and insurance companies, and he was earning hundreds of thousands of dollars a week. But even his fortune did not make Haw Tabor a completely happy man.

What the Duke of Denver really wanted was a career in politics, and he started lavishing money on the state’s Republican Party. When one of Colorado’s seats in the U.S. Senate was vacated in 1883, Haw put himself forward to claim it, but in spite of his largess, the governor, who had the last word, didn’t like him. Tabor took his case directly to the people, and enough of them were moved to march on Denver demanding his appointment to impress the Legislature to give him the job. Haw was sworn in on February 3, 1883; only trouble was it was only a 30-day term.

BACKWOODS DIVORCE

Public scrutiny is the downside of the life of a politician. Two years before he began lusting after a Senate seat, Haw Tabor had quietly divorced his wife. It was such a well-kept secret that even Augusta had no idea it had happened. It was legal enough, though. He had obtained the divorce in a backwoods court where the judge didn’t require both parties to appear, and Haw made sure that the whole thing was covered up by bribing a court clerk to hide the evidence. It was simply done by pasting together pages in the record book.

But nothing is forever. Eventually a new court clerk was hired, and he couldn’t resist the temptation to find out why those pages were stuck together. When he found out, he couldn’t resist another temptation—to seek out poor Augusta and tell her about it.

Needless to say, she was shocked, not to mention hurt and angry, and she hauled Haw into court, charging that he hadn’t supported her for two years and that she had been forced to take in boarders again. He was able to have the case thrown out, but the seeds of scandal had been planted, and to pave the way for his political ambitions, Haw went back to court with his hat in his hand. The hearing was private, but when it was over, he announced that he had generously given his ex-wife a million-dollar settlement.

Augusta, never much of a public figure, dropped completely from sight after that, but she emerged six years later to announce that she had signed a lease on Denver’s Brown Palace Hotel. She and her son Maxcy ran the place. Eventually, Augusta moved to Pasadena, Calif., where she died on February 1, 1895, probably still wondering what had happened to her marriage. One thing that had happened was, of course, Baby Doe.

BEAUTIFUL BABY DOE

Recent divorcee Elizabeth Doe might have met the married Silver King in Leadville as early as the fall of 1879. Certainly they were an item by the summer of 1882. However, the new chapter in Haw Tabor’s life didn’t officially begin until the expensive Washington, D.C., wedding on March 1, 1883, held just two days before his short career in the Senate came to an end. His career in Congress hadn’t attracted much attention, except for the impression he made with flashy jewelry and fancy clothes that left even Chester Arthur, the most fashionable president in American history, in the shade. The wedding was his parting shot, and it left Washingtonians talking for months afterward. The new Mrs. Tabor was said to be the most beautiful bride any of the guests had ever seen.

The gossip around the capital was that Tabor had “kept” Baby Doe back in Denver, and it may have been true. He certainly could afford to. But there was more gossip to come. A few days after the wedding, the Catholic priest who had married them found out that Haw was a divorced man, and as far as the Church was concerned, the marriage was illegal. He was speechless when he found out that the beautiful bride was divorced, too. Haw called a press conference and told reporters that he didn’t understand what the fuss was all about. “The priest never asked us if we were divorced,” he said. But he muddied the waters even more. The ceremony, he confessed, had been pure theater. They had already been married six months earlier in St. Louis.

Haw’s political fortunes soured after that, but his sojourn in Washington allowed him to call himself “Senator Tabor,” which was all he really wanted in the first place. Because of the scandal, he and Baby Doe were to a degree shut out by Denver high society, but if either of them was offended by the snub, they didn’t let it show. With Baby Doe on his arm, Haw was happy and proud. They lived in a fashionable house and entertained important people passing through town. Baby Doe gave birth to two babies, both girls. The first, whom they called “Golden Eagle,” was christened Elizabeth Bonduel Lillie Tabor; the second was named Rose Mary Echo Silver Dollar Tabor, and was known in the family as “Silver.”

Their father lavished huge sums on attempts to become Colorado’s governor, and he campaigned for the Senate again. He also invested heavily in speculative ventures. Then almost overnight his luck turned. His investments started losing money, his mines stopped producing. Even his luck at the poker table began to run out. Nothing seemed to be going right.

Bad went to worse in 1893 when the federal government announced that it was going to stop buying silver for its currency (moving to the gold standard), and the man sometimes known as “Silver Dollar Tabor” was ruined. As his funds dried up in the crash, he even went back to prospecting, but he never had been very good at that. Everything he had was sold, but nothing he was able to do brought in enough to take care of his debts, let alone support his wife and two daughters.

Finally, in 1898, Republican Tabor was able to use what little political influence he had left, ironically with the Democrats, to get a job as Denver’s postmaster. In another twist of irony, it was the same job he had held not too many miles away when fortune first smiled on him. A year after taking the job, on April 10, 1899, Haw Tabor died of appendicitis in the single furnished room he shared with his family. Shortly before his death, he reportedly told his still young second wife to “hang on to the Matchless Mine.”

LEGACY OF BABY DOE

Haw Tabor really didn’t have much left to give Baby Doe except that played-out mine in the hills above Leadville. In the 20 years that he had owned the Matchless, the mine had produced profits on his investment hundreds of times over. He had chosen never to part with it because he was convinced that when silver came back the mine would be the new El Dorado.

Baby Doe’s brother worked for Tabor in better days and had become comfortably wealthy. But she refused his offers of help and instead packed up her teenage daughters and went back to Leadville, where she took up residence in a shack next to the Matchless mineshaft. The girls didn’t stay with her very long. The Golden Eagle was first to fly. She went to Chicago, where she ultimately got married and managed to vanish without a trace. Silver announced that she was going to enter a convent and nearly succeeded in vanishing herself. Instead she became an alcoholic, and died in Chicago under mysterious circumstances—some said she had been murdered—in the 1920s.

Their mother, meanwhile, kept up her search for the silver her husband had told her was still deep in the Matchless Mine, a single-minded quest that would have put any old sourdough to shame. By day she sloshed around the bottom of the pit wearing knee high boots and dirty overalls. By night she guarded her treasure with a shotgun on her knee—although, of course, no one but she believed there was any treasure to guard.

She kept up her fruitless search in all kinds of weather for about 35 years. A severe snowstorm struck the Leadville area in March 1935. On the 7th, neighbors heard no sounds coming from the mine and saw no smoke rising from her cabin chimney. Nobody had seen her for at least a week. Two neighbors pushed through the snowdrifts to investigate, and found 81-year-old Baby Doe frozen to death on the floor of her cabin. At one time she had been one of the wealthiest women in America, but for most of the time after Haw’s death she had relied on the generosity of her neighbors for the bare necessities. She was buried next to her husband in Denver’s Mount Olivet cemetery.

In the end, beautiful Baby Doe became a symbol of gritty determination and hard work, while Haw Tabor is mostly remembered for his dumb luck and for how such luck inevitably ran out. But there is something to be said for luck. Without it, there would have been no monstrous fortune to lose and no matchless Baby Doe to pamper.

Bill Harris writes from Dallas. Suggested for further reading: Horace Tabor: His Life and the Legend, by Duane A. Smith; and The Legend of Baby Doe, by John Burke and Richard O’Connor.

Originally published in the August 2007 issue of Wild West.