Many years of speaking about Civil War topics has taught me that some military leaders elicit almost universal scorn. Mentioning them prompts members of audiences to smile, chuckle, and nod knowingly, as if they are in on a joke that does not even require a good punchline—the mention itself is the punchline. Brief pauses when saying the generals’ names heightens the effect: for example, Ambrose (pause) Everett (pause) Burnside, or Theophilus (pause) Hunter (pause) Holmes. Adding something about Burnside’s whiskers or Holmes’ nickname “Granny” removes almost any chance that listeners will take either man seriously. The fact that neither Burnside nor Holmes possessed much martial talent renders them easy targets, but soldiers of considerably more substance, including Braxton Bragg and John Pope, also suffer from the punchline syndrome.

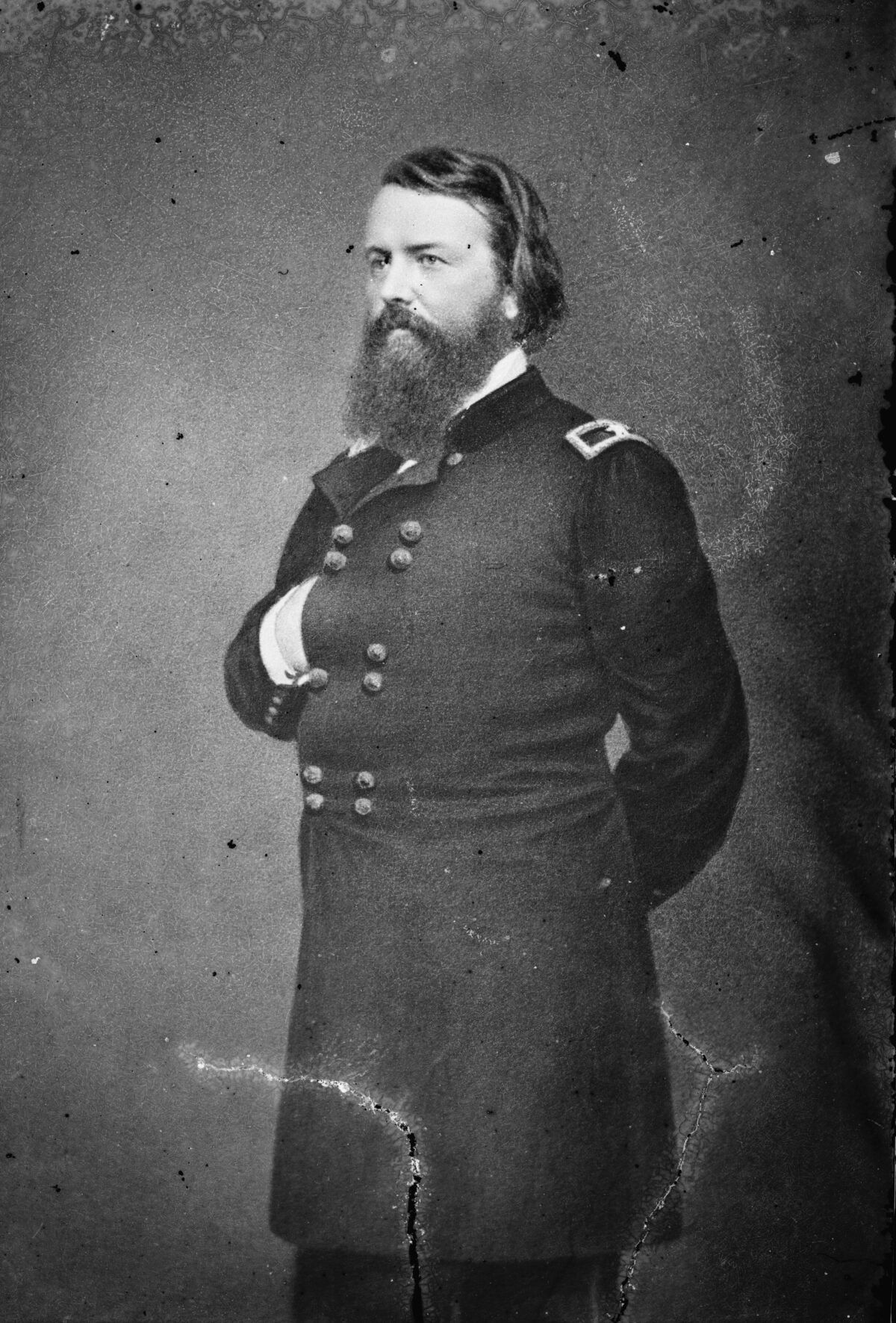

A closer look at John Pope will illustrate this point. Pope’s popular reputation rests almost entirely on his conduct as commander of the Army of Virginia in July and August 1862, a period that ended with the general’s defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run and his reassignment to Minnesota. Public perceptions combine images of Pope as a man widely mocked, just as widely disliked, and removed in September 1862 as a figure of importance during the war.

Pope appears most ridiculous for allegedly issuing orders that located his headquarters “in the saddle.” None of his orders contained that language, but the slur has stalked him from the summer of 1862 to the present. In late July 1862, a newspaper in Kansas remarked that “Gen. Pope says he means to make his head-quarters in the saddle. Officers usually have their hind-quarters there.” Other Northern papers echoed this sentiment, as did some of their counterparts in the Rebel states. Confederate artillerist Edward Porter Alexander recalled, incorrectly, that Pope’s first general order to the Army of Virginia was headed “Headquarters in the Saddle, 1862.” The fabricated heading “was reprinted in all the Southern papers, &, with it, a sort of defiant reply of the South, that a general who did not know his headquarters from his hindquarters had better be kept out of General Lee’s way.” Alexander employed a dismissive flourish to compare Pope’s overall conduct at Second Bull Run to “a plot from a comic opera.”

Extending his assault on Pope’s character and military standing to the antebellum years, Alexander asserted that the Union general’s “reputation in army circles…was that of a blatherskite.” Returning to his humorous tone, Alexander mentioned an army ditty about when Pope “was stationed for some years on the ‘Llano Estacado’ or Staked Plains of Texas trying vainly to get water by boring artesian wells. The song had it: ‘Pope told a flattering tale / Which proved to be bravado, / About the streams which spout like ale / On the Llano Estacado.’”

Union Brig. Gen. Samuel D. Sturgis figured in another anecdote that has clung doggedly to Pope. During a dispute with Herman Haupt, who oversaw the use of railroads during the Second Bull Run Campaign, Sturgis bridled at the suggestion that his conduct might cause “serious delays…in the forwarding of troops to General Pope.” Haupt described how Sturgis, in an “excited tone,” exclaimed: “I don’t care for John Pope a pinch of owl dung!”

Pope’s statements and actions in the summer of 1862 also provoked vituperative responses from both Federals and Confederates. When he arrived in Virginia from the Western Theater, he promised a new approach to subduing the Confederacy. In line with congressional Republicans who favored applying harsher policies, Pope announced that he would seize civilian property, hang guerrillas, punish civilians who aided them, and otherwise chastise all Rebels. His address to the Army of Virginia dated July 14, 1862, also included a statement implicitly critical of George B. McClellan that offended many of the soldiers who read it: “I have come to you from the West, where we have always seen the backs of our enemies; from an army whose business it has been to seek the adversary and to beat him when he was found; whose policy has been attack and not defense.”

Pope did not follow through with all of his threats, but Confederates, as well as conservatives and McClellan’s admirers within the Union Army, reacted passionately. Robert E. Lee typified many Confederate reactions to Pope’s vision of a harder war. In late July 1862, he wrote Secretary of War George Wythe Randolph that he hoped to “destroy the miscreant Pope.” (The 19th-century meanings of “miscreant,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary, included “depraved, villainous, base” [adjectives] and “a vile wretch, a villain, rascal” [nouns].) Elsewhere Lee stated that Pope must be “suppressed.” Brig. Gen. Marsena R. Patrick, who led a brigade in the Union 3rd Corps, pronounced Pope’s address of July 14 “very windy & somewhat insolent.” Three days later, Patrick claimed, “This Order of Pope’s has demoralized the Army & Satan has been set loose.”

Although soundly defeated at Second Bull Run and quickly removed from the principal arenas of action, Pope maintained a good reputation among key Union figures. In November 1864, General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant requested that the Departments of the Northwest, Missouri, and Kansas “be erected into a Military Division and that Genl Pope be assigned to the command. I think it highly essential that the territory embraced in these three Depts should all be under one head.” Grant predicted “intelligence of administration” under Pope, and the appointment went forward.

An overview of John Pope’s military career reveals far more that is positive than negative. Second Bull Run stands as his greatest failure, and partisan treatment of Fitz John Porter did him no credit (though Porter, together with his friend McClellan, could have helped Pope more during the campaign). Apart from Bull Run, Pope’s record boasts two brevets for gallantry in Mexico, success at Island No. 10 and elsewhere in the Western Theater in 1861-62, and credible service in Minnesota and as commander of the military division Grant proposed in 1864. After the war, he played a leading role in Reconstruction and during the Indian Wars (like O.O. Howard, he argued for improved treatment of Native Americans). He deserves better than relegation to a punchline. ✯