The 600 tablets scattered about the site tell the story of the battle with color coding and precise placement

As Shiloh National Military Park chief ranger, Stacy D. Allen wears many hats besides the distinctive, wide-brimmed “flat hat” that has been part of the National Park Service official uniform for almost 100 years.

The no-nonsense Allen is a historian, a tour guide, a coordinator of visitor relations, and a personnel manager, supervising a staff of about two dozen that maintains the remarkably well-preserved, 5,065-acre battlefield along the Tennessee River.

But he’s also an art curator. One of his most significant roles—taking care of the more than 600 historical tablets at the rural Tennessee battlefield—is unknown to most of the park’s more than 500,000 annual visitors.

Those works of art are scattered throughout Shiloh—in ravines; in the aptly named “Lost Field” deep in the woods; in a cemetery surrounded by modern graves; at the edge of a busy state road; and even on an ancient Native-American mound. Some may be found on private property, nearly obscured by tall grass and rarely viewed by the public.

Many of Shiloh’s masterpieces are fragile, not unexpected given nearly all are well over 100 years old. The artwork comes in distinct shapes and sizes. Various colors, too. Shiloh art sometimes is the target of thieves or a victim of wayward drivers. Fallen tree limbs take their toll, unsurprising because the battlefield is 85 percent forest. Some battlefield artwork suffers from ravages of time, weather, and disrespectful birds.

When the color-coded, cast-iron historical tablets that make Shiloh special need touch-ups, “I help paint them myself,” Allen says, pounding a table half in jest in the park’s visitor center. Allen pitches in because “Shiloh is in my blood,” he says. “It’s my passion.”

Allen, 62, is a native of Kansas, but his great-great grandfather Solomon Morrison Osborn was a private in the 40th Illinois who fought in the battle that resulted in nearly 24,000 casualties on April 6-7, 1862.

In the years immediately after the war, the Shiloh battlefield looked much different than its present-day, parklike setting. Under lurid headlines “Bodies of Soldiers Buried in Gullies” and “Human Flesh Devoured by Hogs—A Frightful Picture,” a Memphis Daily Argus correspondent set the scene on the fourth anniversary at an area of the battlefield that saw hard fighting.

“For hundreds of acres nearly all the undergrowth was cut off, or split into ribbons, a little over breast high, by minnie balls,” he wrote, “and the trees, large and small, are literally filled with shot holes to the height of twenty feet.”

In Rea Field, a short distance south of the site of the wartime Shiloh Church, the correspondent found a gruesome scene: “I saw where a large number (supposed to be one hundred and fifty, at least) of Confederates had been tumbled into a gully and covered up with a thin layer of dirt, and this they called burial!”

Federal dead, he wrote, were “buried at the proper depth, and generally with head and foot-board, inscribed with the names, companies, regiments, etc.” Unlike most of the Confederate burial trenches, which were “rooted up by hogs,” the correspondent saw only one Federal mass grave desecrated by the farm animals, “and that was but slightly.”

Horrified by such stories, veterans who visited the battlefield pushed for the hallowed ground to be preserved. Two days after Christmas in 1894, Congress established Shiloh National Military Park. David W. Reed, a 12th Iowa veteran who had been wounded at Shiloh, eventually became park superintendent and was instrumental in marking his treasured field.

By 1908, 651 tablets cast at a foundry in Chattanooga, Tenn., were placed on the battlefield. Reed—“The Father of Shiloh Park,” according to noted battlefield historian and author Timothy B. Smith—determined the colors, inscriptions, and positions of the markers.

(The original tablets cost about $25 apiece, Allen said. Replacements today can cost from $2,000–$3,000, plus the cost of labor to install them. The markers are painted every three years on a rotating basis.)

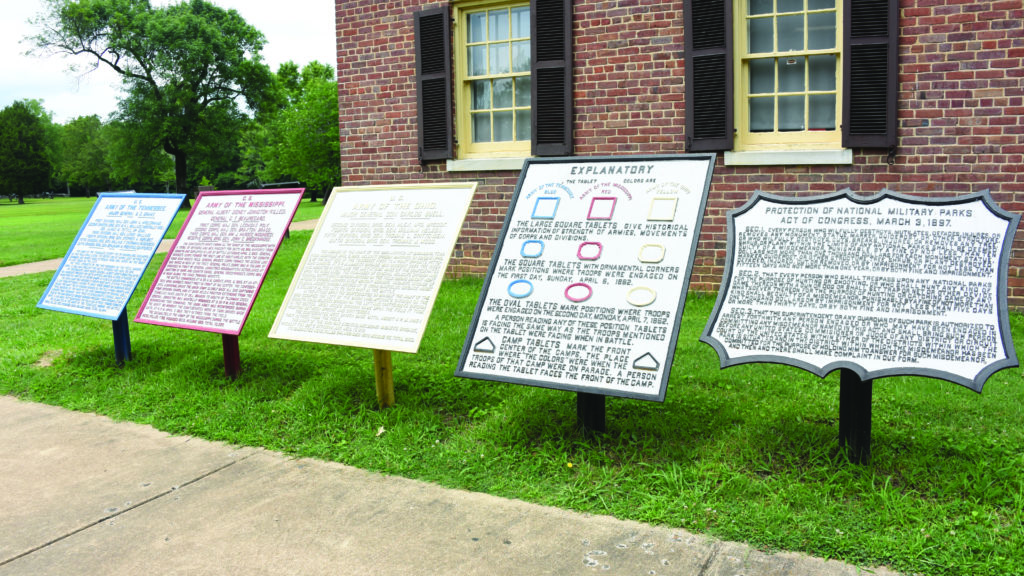

Near the massive, beautiful Iowa Memorial, a short distance from the park’s visitor center, a large black-bordered, early 20th-century tablet explains the meaning of each: Blue-bordered tablets represent the Union Army of the Tennessee; yellow-bordered the Union Army of the Ohio; and red-bordered the Confederate Army of the Mississippi. Large, square tablets inform of the strength of armies and movements of corps and divisions. Square tablets with ornamental corners mark where troops were engaged April 6, 1862, the first day of the battle. Oval tablets designate the same information about the battle’s second day.

“A person reading any of these position tablets,” the explanatory tablet notes, “is facing the same way as the troops mentioned on the tablet were facing when in battle.”

Shaped like a home plate in baseball, black-and-silver tablets mark the front center of camps. That’s where the “colors” were located when the troops of that camp were on parade. Smaller markers designate other notable battlefield locations, such as Bloody Pond, the infamous Hornets’ Nest and site of the first-day surrender of troops under Union Brig. Gen. Benjamin M. Prentiss. Fabulous star-like, 10-sided markers on poles atop a pyramid of cannonballs mark headquarters sites of Union brigades.

Every tablet has a story, some more compelling than others. One of the most interesting marks the spot where the highest-ranking Confederate officer on the battlefield bled to death from a bullet wound below his right knee—even though he may have had a tourniquet in his pocket.

In early April 1896, U.S. Senator Isham Harris, a Confederate veteran and former Tennessee governor, visited the battlefield for the first time since April 1862. Harris, as a member of Confederate Army commander Albert Sidney Johnston’s staff, had witnessed the wounding and death of the 59-year-old general on the battle’s first day. Harris wanted to identify Johnston’s death site, a subject of controversy since the engagement ended.

Harris traveled the hallowed ground with Reed, who was eager to identify and mark the Johnston site, and former Union Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell, whose fresh troops were instrumental in securing a Federal victory on April 7. Near the wartime Sarah Bell Farm, Harris asked to be alone. Then the 78-year-old veteran went a short distance into a nearby ravine. “This is the place,” he said upon finding the death site, according to Smith’s book on the history of the park. “I cannot be mistaken.”

In 1902, Johnston’s wounding site—also identified by Harris—was marked with a large monument that includes pyramids of 8-inch shells and an upright 30-pounder Parrott Rifle tube. A bronze plaque on the old cannon notes the time of Johnston’s mortal wounding: “2:30 p.m., April 6, 1862.”

Fifty yards away, in the ravine, a large, red-bordered tablet marks the spot and time—2:45 p.m.—of Johnston’s death. In raised, red letters, visitors may read details of Johnston’s death from Harris.

“General are you hurt?” Johnston’s former aide is quoted on the marker.

“Yes,” came the reply. “I fear seriously.”

In woods, about 40 yards off Eastern Corinth Road in the national park, raised blue letters on a marker atop a Federal blue-painted pole jar a first-time visitor to the site: “Burial Place 16th Wisconsin Infantry. Bodies removed to Nat’l Cemetery.” Immediately in front of the marker is a depression in the ground, about 10 yards long, probably remains of a trench where some of the Badger State soldiers were first interred.

Twenty-nine of these simple markers in the park denote original burial sites of Federal troops, stark evidence of a brutal fighting that resulted in nearly 1,800 dead in the two Union armies. Beginning in 1866, Federal dead at Shiloh and other battlefields were disinterred and reburied in newly created national cemeteries. The five known Confederate burial trenches at Shiloh are marked by red-and-silver painted tablets of similar design. Those soldiers remain buried on the battlefield.

A weather-beaten marker in need of TLC denotes the unusual, original location of 28th Illinois dead: atop a prehistoric Indian mound near the Tennessee River and Dill Branch Ravine. The makeshift grave site on the earthen mound—one of three such mounds at Shiloh—was chosen by 28th Illinois Captain Hinman Rhodes.

Dismayed by the obliteration of U.S. graves in Mexico during his Mexican War service, Rhodes was determined that the burial place of the more than three dozen dead of his regiment be preserved, according to a 1922 battlefield history. And so the Prairie State’s fallen were originally interred atop the Indian mound, “Shiloh’s greatest Pyramid,” then removed after the war.

“While it is true that, years ago, the remains of these were taken up and reinterred in the National Cemetery,” the 1922 history noted, “yet this grateful Government of ours has erected a solid and enduring marker beside the vacant trenches to point out the original burial-place of these heroes to all the world for time to come.”

Allen, chief ranger at Shiloh since 2002, says the tablets are a reminder of how lucky we are that the veterans diligently marked their battlefield.

“They are tangible objects that when you look and touch them, you’re looking at and touching previous generations,” he says, “and touching their history and humanity.” ✯

John Banks is the author of the popular John Banks’ Civil War blog. He lives in Nashville, Tenn.

This Rambling column appeared in the August 2020 issue of Civil War Times.