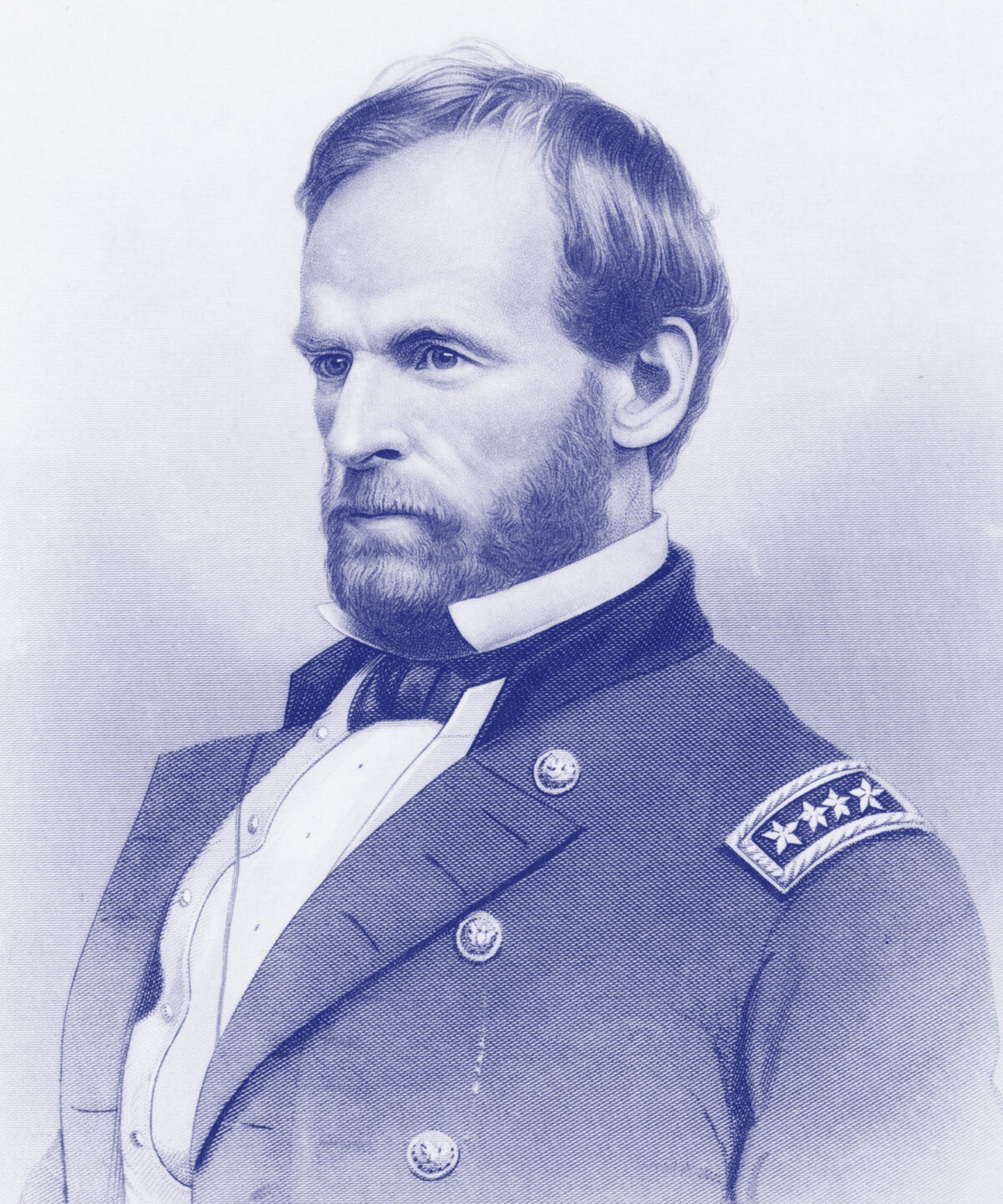

William Tecumseh Sherman was finally perched where he wanted and could best operate by the spring of 1864. He had been promoted to brigadier general of Regulars and even better, he had finalized his relationship with Ulysses S. Grant. His Herculean labors were over, and he was now truly the trusted associate of the man just designated to run the entire war effort in the East.

Sherman was ruefully aware of Southern tenacity: “No amount of poverty or adversity seems to shake their faith….I see no signs of let up—some few deserters—plenty tired of war, the masses determined to fight it out,” he wrote his wife Ellen in March 1864, just before meeting with Grant in the first of a series of strategy sessions that culminated in Cincinnati. The intent was to engage in great battles and shatter Confederate field forces, not just Sherman and Grant, but everybody—Nathaniel Banks’ Army of the Gulf would move on Mobile, Ala.; Benjamin Butler’s Army of the James would head up the Virginia Peninsula toward Richmond; and Franz Sigel would traverse the Shenandoah Valley—all of them supposed to be looking for a fight. The days of episodic combat were over; Grant and Sherman would present the Confederacy with one apparently never-ending battle until it bled to death.

Consider the bedraggled Army of Tennessee (not to be confused with the Union Army of the Tennessee) facing Sherman in the spring of 1864. It was soon to be 65,000 strong, many of the men veterans and famously ferocious fighters. But its commander, General Joseph E. Johnston, could not ask them to take the offensive, to engage in slugfests like Chickamauga and expect positive results. He understood Sherman was coming to try to destroy his army. He would resist behind fortifications where his men were safer and could maximize their veteran marksmanship.

Sherman was more than ready, at the height of his strategic powers and with almost the perfect force at his disposal. He had a combat-hardened legion of nearly 100,000 commanded by trusted subordinates—Maj. Gen. George Thomas’ Army of the Cumberland, now numbering 60,000; the Army of the Tennessee with 25,000 tough troops under Grant– Sherman protégé Maj. Gen. James P. McPherson; and finally, Maj. Gen. John Schofield, with his Army of the Ohio adding another 14,000.

Sherman also had an exceptional grasp of the terrain they would be covering. It was certainly challenging, filled with mountainous slopes, steep ravines and dense forests. Sherman had explored it extensively, working with the inspector general in the 1840s, and there it remained in his personal geospatial database.

Near the end of March, Sherman met with his three army commanders at his Chattanooga, Tenn., headquarters and set about planning the campaign. They all wanted and expected a decisive battle with Johnston. When that would come remained a question, but the intent was to keep advancing until it did and to ensure that all elements of the force operated together.

This meant supply by rail, which almost dictated a general line of advance along the tracks of the Western & Atlantic, linking Chattanooga to Atlanta. Sherman went to elaborate lengths to calculate the exact number of carloads necessary (145) and then proceeded to commandeer and cajole (“If you don’t have my army supplied and keep it supplied, we’ll eat your mules up sir—eat your mules up”) until he got what he wanted. Large-scale positional warfare made such a link necessary, but it also sent a political message—this was an invading army that could stabilize its position deep in enemy territory. Foraging was certainly useful, but it turns an army into a shark that must keep moving to survive. Sherman’s intent here was different.

Johnston was waiting for him at Dalton, Ga., with at least 50,000 troops deeply entrenched along an 800-foot-high ridge called Rocky Face, which the Western & Atlantic pierced at Buzzard Roost. Sherman seems to have grasped intuitively what was happening and declined to throw his men at such objectives if there was an alternative. Intent on saving them from what he called “the terrible door of death” at Buzzard Roost, he had Schofield and Thomas stage a demonstration there to fix Johnston’s attention, while sending McPherson on a wide sweep to the right through Snake Creek Gap to get in behind Johnston and cut his rail link at Resaca. The deft move set the pattern for the entire campaign.

Sherman almost scored a knockout in the first round. On May 9, McPherson and the Army of the Tennessee poured through Snake Creek Gap and got within a mile of Resaca when they encountered some earthen fortifications manned by a rear guard that turned out to be about 4,000 strong. Had McPherson attacked promptly, Johnston would have been trapped. Yet he hesitated and dug in instead. “Well Mac, you have missed the great opportunity of your life,” Sherman told him later.

But all was hardly lost. Johnston was immediately forced to give up his defenses at Rocky Face Ridge and set up around Resaca. May 14-15 brought several more sharp actions, and once again Johnston found himself on the verge of being flanked by McPherson and retreated south toward Cassville, 25 miles down the tracks.

Here, it looked as if Johnston would at last strike out, as one of his corps commanders, John Bell Hood, had been urging all along. The quintessence of Southern aggressiveness, Hood had been schooled by Robert E. Lee in the Army of Northern Virginia, and his body was now a monument to the costs of taking the offensive, having lost the use of his left arm at Gettysburg and his right leg at Chickamauga. Still, his division had led the assault that ruined Union commander Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans, and he could always be counted on to attack—or so Johnston thought when he believed he had Sherman where he wanted him.

In hot pursuit, the Union commander had sent the columns of his army along several roughly parallel roads across a front of about a dozen miles. Johnston reacted by concentrating most of his forces under Hood and Polk in order to strike two of Sherman’s corps seven miles separated from the rest. The Rebel troops seemed anxious for a fight, but at the last minute Hood uncharacteristically worried about being flanked himself and aborted the attack.

This meant another 14-mile retreat from Cassville southeast to the Allatoona Pass, where slaves had already constructed defensive works overlooking the railroad along the Etowah River. It was an ideal place to make a stand.

But Sherman knew that from his days exploring the pass as a lieutenant in the 1840s and had already resolved to go nowhere near it. Instead he gave his troops a rest, repaired the railroad and then brought forward 20 days’ worth of supplies, enough to cut loose for another grand sweep around Johnston’s left.

It began on May 23, the objective was Dallas, and now the whole army would move: Schofield on the left, Thomas in the middle and McPherson as usual on the right. This time Johnston caught on and was able to shift his own force along the inside path so they reached New Hope Church near Dallas and entrenched before the Federals arrived. When they did, fierce firefights erupted on May 25 and 27, so fierce that the men remembered the place as “the Hell Hole.”

Afterward, both sides fell into a pattern of skirmishing and sniping, each probing for a place to attack or an angle for maneuver, in this terrain a deadly form of blindman’s bluff. At Pickett’s Mill, Sherman tried to turn the Confederate positions and ended up taking 1,600 casualties. But gradually he was able to work his way around, by sending McPherson and Thomas to the left and Schofield to the right. By the end of the first week in June, they were astride the Western & Atlantic near Marietta— but once again facing Johnston and the Confederates, now formidably entrenched in a line across Kenne saw Mountain.

Despite his success at moving Johnston around like a distressed chess piece, Sherman became increasingly agitated as this campaign progressed. The farther Sherman’s army progressed, the more railroad there was to protect, and the losses in manpower weren’t trivial. The men necessary to guard his rail link all the way back to Louisville were nearly equal to the number of his combat troops, and the toll seemed to grow by the foot, the recent fighting having necessitated garrisons at Dalton, Kingston, Rome, Resaca and now Allatoona Pass. Considering what had happened elsewhere, his military situation was good and the rails were being repaired practically as fast as they could be broken up. But keeping them open was vital to the kind of campaign he was waging, and he was bound to worry.

Thus far, his campaign had gained a lot of ground and cost relatively few casualties but failed to produce a decisive victory. Meanwhile, his preferred approach, flanking, was being complicated by incessant rain that had turned the roads to gumbo, and he didn’t want to leave the Western & Atlantic supply link under such circumstances. In his mind, there were but two choices: Wait until the roads dried and he could accumulate surplus supplies; or attempt a frontal assault on the dug-in Confederates.

On June 5, he told Henry W. Halleck, Grant’s chief of staff in Washington, he would “not run head on his fortifications,” but as the month dragged on, he gradually reached the opposite conclusion. Since the enemy and even his own subordinates thought he would never attack head-on, he would “for moral effect” do exactly that. If it succeeded, he would not just put an end to the “belief that flanking alone was my game,” he would cut Johnston’s forces in half and rout them—exactly the kind of victory the Union so desperately needed.

The attack came on June 27, aimed at the southern spurs of Kennesaw Mountain. It began badly and then degenerated. The temperature climbed above 100 degrees. The Rebels’ fire was accurate and brutal. Eventually, a few bluecoats got within feet of the gray entrenchments, but most had been pinned down or simply shot. By the midafternoon, around 3,000 Union soldiers had been killed or wounded, nearly four times the Confederate casualties. At this point, Sherman resorted to one of his best military traits: He recognized he was beat and cut his losses.

He had already seen a great deal, but Kennesaw seems to have had a chastening effect. “It is enough to make the whole world start at the awful amount of death and destruction…,” he wrote Ellen; “I begin to regard the death and mangling of a couple thousand men as a small affair, a kind of morning dash.” After hearing from George Thomas that “one or two more such assaults will use up this army,” Sherman let it be known that futile frontal attacks were over. There would be more hard fighting, but nothing suicidal.

Instead, Sherman waited until the roads dried and he had enough supplies to leave the tracks. Then he sent McPherson and the Army of the Tennessee surging around the right, south toward the Chattahoochee River. It worked again. With the Yankees in behind him, threatening his rail connection, Johnston had no choice but to withdraw from Kennesaw Mountain on July 2.

At this point, the game changed. Instead of Johnston’s army, Atlanta itself became Sherman’s objective. For other than Richmond, there was no greater prize in the Confederacy. Over the course of the war, the city’s population had doubled to 20,000 as it added foundries, munitions plants, gun factories and supply depots, all of which sprang up naturally at this key rail hub. If the South had a workshop for war, it was Atlanta. And now Sherman was closing in.

Flanked and flanked again, Johnston fell back to the Chattahoochee, crossed the river, and took up secretly prepared positions on its banks by the end of the first week in July. On the other side, one officer remembered seeing Sherman and Thomas together with the prize now clearly in view: “Sherman stepping nervously about, his eyes sparkling and his face aglow—casting a single glance at Atlanta, another at the River…to see where he could cross…how he best could flank them. Thomas stood there like a noble Roman, calm, soldierly, dignified; no trace of excitement.”

On July 9, Sherman wrong- footed the Rebels, having McPherson feint in his usual direction, while sending Schofield quietly several miles upriver from Johnston’s right for a surprise crossing in the face of nothing more than cavalry pickets. For the umpteenth time, it seemed, Johnston found himself outmaneuvered and was forced to withdraw, this time to trenches in back of Peachtree Creek, just four miles from center city.

Meanwhile, Jefferson Davis had lost all patience with Johnston and sent his new military adviser, none other than Braxton Bragg, on what amounted to a predigested fact-finding mission. When he arrived he spoke mainly to John Bell Hood, who wanted Johnston’s job. “We should attack,” he told Bragg, advice that was bound to be well received by the Confederate president. Hood was his kind of general, and although even Robert E. Lee warned against him (“all lion, none of the fox”), Jefferson Davis had pretty much decided on him as Johnston’s replacement, when on July 16 the latter made it a certainty by hinting he would withdraw his maneuver forces and turn over the city’s defense to the Georgia militia. That did it. The next day, the 33-year-old Hood became Atlanta’s chief defender. He, at least, would not give up without a fight. Frequently dosed with the opiate laudanum for his almost constant pain, Hood had sacrificed his body on the altar of war and expected the same of his men. He had no regard for their lives, and they knew it.

On July 20, to no one’s surprise, he attacked. Sherman had sent his three armies sweeping toward Atlanta’s final rail link to the upper South, and Hood thought he could catch Thomas, who was separated from the others, as he was crossing Peachtree Creek. But he was several hours too late and found himself instead in a stubborn firefight that cost him 3,000 men and yielded no appreciable result.

Hood was just getting started. After withdrawing into the city’s defensive ring, that night he sent one of his corps out again on an all-night march to attack what he thought would be McPherson’s exposed flank. It proved less exposed than expected, and once the Yankees got over their surprise, they fought ferociously, counterattacking at the end of the day and inflicting another 5,000 casualties—8,000 in two days, more than Johnston had lost in 10 weeks.

The Rebels did exact a significant price: McPherson himself. After meeting with Sherman, he blundered into a gaggle of Confederates and in attempting to escape was shot out of the saddle. They brought the body back, and Sherman had it laid out on a door. Pacing back and forth, tears streaming down his cheeks, he took turns giving orders as reports came in and bemoaning the fate of this 34-year-old golden boy.

Sherman replaced him with Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard, an Army of the Potomac transplant. When Sherman sent Howard sweeping around in the direction of Atlanta’s last rail link, Hood reflexively sent a corps to attack them at the Ezra Church crossroads on July 28. Sherman learned of the assault and was elated: “Just what I wanted, tell Howard to invite them to attack, it will save us trouble…they’ll only beat their own brains out….” That’s what they did: making six separate charges and taking another 5,000 casualties, only to give up the attack and entrench themselves.

In eight days, John Bell Hood managed to carve the heart out of his army. He had little choice now but to settle into the fortifications that ringed Atlanta and try to recuperate.

Meanwhile, Sherman took advantage of the pause to soften up the city with siege artillery and further disrupt communications by sending cavalry well south to tear up the railroad. This they did, but only temporarily, as the Confederates were able to make repairs.

To the ever-hopeful Southern press, it looked as if the city were holding out, even interpreting Hood’s self-defeating assaults as wins. The Atlanta Intelligencer, which tellingly was being printed in Macon, went so far as to suggest: “Sherman will suffer the greatest defeat any Yankee General has suffered during the war….The Yankee forces will disappear before Atlanta before the end of August.”

Actually that is what happened, but not because of any Union defeat. After Army of the Ohio cavalry commander Maj. Gen. George Stoneman was captured near Macon on August 9, Sherman decided that truly cutting the railroad and sealing Atlanta’s fate required moving the main army across it well below the city. He made his move on August 26 after nearly a month of preparation, removing six infantry corps from the trenches and heading south.

Hood thought the city was saved, until he realized the Yankees were now tearing up huge stretches of track unmolested. He sent out two corps to stop them, and on August 31, heavily outnumbered, they assaulted well-entrenched Union forces at Jonesborough, 20 miles south, only to be thrown back with heavy and disproportionate losses. The next day, Sherman staged a counterattack with his XIV Corps under the coincidentally named and even more ill-tempered Jefferson C. Davis. The fighting proved brutal, at times hand to hand.

Atlanta’s lifeline was officially severed. That night, Hood burned or blew up the military supplies he couldn’t carry and then evacuated the city to join the rest of his weary field army. On September 2, blue-clad forces replaced them, and Sherman wired Halleck: “So Atlanta is ours, and fairly won.”

A wave of joy and relief swept over the North, and cannon salutes boomed from its cities. Combined with Admiral David Farragut’s victory at Mobile Bay, which stoppered the last blockade running port east of Texas in early August, the capture of Atlanta and its war industries dealt a devastating strategic body blow to Southern hopes of somehow emerging victorious.

Of still greater importance, it had the inverse effect on the career prospects of Abraham Lincoln, who had been facing what amounted to the Grim Reaper in November. Instead, the path to victory in the presidential election of 1864 was now not only open, but wide open.

Saving Lincoln would have been enough for most men, but William Tecumseh Sherman, in his sweet spot at last, was just getting started.

Originally published in the June 2014 issue of Civil War Times. To subscribe, click here.