Artist’s Arabian Nights home on the Hudson was almost lost

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]IX HUNDRED FEET above the Hudson River towers Olana, a fantastical mansion conceived and constructed by landscape painter Frederic Edwin Church. In the summer of 1966, Church was long dead and Olana in peril of being torn down—until a day in late June when a helicopter landed in the yard. From the aircraft emerged New York Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller. After greeting a crowd and touring the idiosyncratic 19th-century home, Rockefeller spoke briefly of its historic significance, then signed a bill authorizing the state to acquire the property.

The autocratic politician may have stage-managed his appearance for publicity, but the urgency was real: Olana’s trove of paintings by Church and other

artists already had been removed to be readied for auction, and almost everything else of value cataloged and tagged for transport. With his 11th-hour intervention, Rockefeller, who had demolished 98 acres of old Albany to build a monolithic state-office complex, allied with the emerging cause of historic preservation.

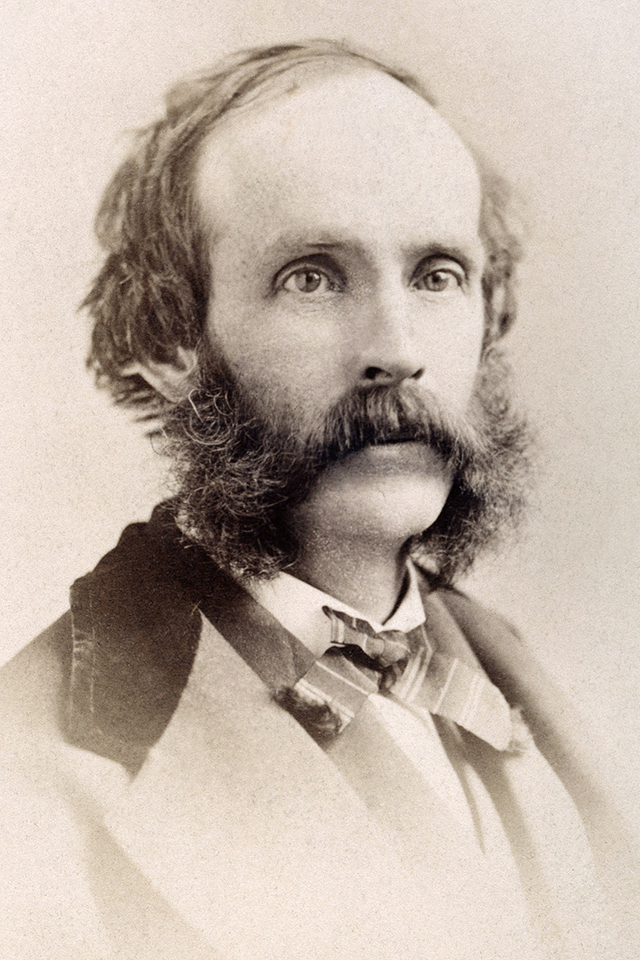

In 1844, preeminent landscape artist Thomas Cole took an 18-year-old protégé to sketch with him along the Hudson River on a bluff affording spectacular views of the Berkshire and Catskill mountains. Located across the river from Cole’s home in the village of Catskill, 110 miles upriver from New York City, the overlook was part of the majestic terrain that had brought Cole his earliest renown. These vistas would propel Cole’s student, Frederic Edwin Church, to such success that eventually Church could build on the bluff a house that many admirers call the greatest of the younger artist’s works—in the words of art expert Franklin Kelly, “the single most important artistic residence in the United States, and one of the most significant in the world.” If not for a preservation campaign that began with one man and ended as a movement, Church’s unique residence would have been destroyed or altered beyond recognition. The painter, not only a technically bravura artist but a born showman, would have appreciated the drama surrounding the rescue of his beloved country home, and its role in a new appreciation for his art.

Olana mattered—and matters—because of the property’s connection to the Hudson River School, the first American art movement to break from traditional European techniques. Cole, widely regarded as one of the pillars of the Hudson River School, along with Church and peers like Asher B. Durand, Jasper Cropsey, and Albert Bierstadt, painted exalted depictions of a natural world in harmony with divine order, manifest destiny, and the young nation.

Having emigrated from Lancashire, England, Cole painted in New York City, initially without much success. In 1825, he sailed up the Hudson in search of transcendent wilderness and found it upstream among the mountains. Cole moved to Catskill, a mountain village, and married his landlord’s niece. The couple later inherited her uncle’s house and property, called Cedar Grove.

Cole’s theologically illumined landscapes brought him recognition, buyers, and, in 1844, an ambitious overture from young Church, a financier’s son from Hartford, Connecticut, to study with the Hudson River painter. “I have frequently heard of the beautiful and romantic scenery around Catskill,” Church wrote. “It would give me the greatest pleasure to accompany you in your rambles about the place observing nature in all her various appearances.”

Cole did not accept students. However, art patron Daniel Wadsworth, founder of Hartford’s Wadsworth Atheneum museum and a friend of Church’s father, interceded. The Wadsworth endorsement and $300 a year from Church senior persuaded Cole to take the youth, already a remarkable draftsman,

(The Granger Collection, New York)

as a student. Church lodged at Cedar Grove in an attic bedroom and painted with his mentor in Cole’s studio, absorbing his teacher’s Arcadian perspective. Each felt a spiritual connection to nature and saw in wilderness a manifestation of the divine. Church was only 19 when the prestigious National Academy of Design accepted two of his landscapes for exhibition. Cole never took another student.

In 1847, after two years with Cole, Church moved to New York City, establishing a studio in the Art Union building at 497 Broadway. In 1848, the National Academy made him a member in full, the youngest artist ever so honored. Cole’s death that year at 47 after a brief illness deeply saddened Church. He kept the older artist in mind all his life, an influence that extended to his choice of a home site.

Church made sketching jaunts to the Catskills, the Berkshires, the Green Mountains, and into Maine and Canada, making field studies that he worked into paintings in his studio. He came to eschew Cole’s allegorical fervor, still invoking the sacred in nature but with a virtuoso realism, especially in his approach to light. Church’s glowing sunrises, lowering skies, and luminous clouds delighted critics and public alike. After a Canadian sojourn, he began “Niagara,” depicting the falls that had attracted Cole and other artists.

Forgoing a grand tour of Europe’s art capitals for inspiration, Church instead followed in the footsteps of peripatetic Prussian scientist, explorer, and author Alexander von Humboldt, who in his sensational book Cosmos chronicled his South American explorations.

In 1853, Church extensively toured Colombia and Ecuador, lodging at a hacienda where Humboldt had stayed decades earlier. Becoming one of the first “artist-explorers,” Church visited tropical jungles, volcanoes, and primordial stone formations. To sketch the Andes, the painter undertook arduous treks along the cordillera.

Church’s South American paintings did well but he took the art world by storm when he finished “Niagara,” a grand canvas three-and-a-half feet high and seven-and-a-half feet across. Not even Cole had approached the waterfall’s cataclysmic force as Church did.

Framing the falls from the Canadian shore without foreground, “Niagara” places the viewer’s eye at a precipice. Displayed by itself at a New York gallery in 1857, “Niagara” became an event. Customers by the thousands paid a 25-cent admission fee to be astounded by the painting’s compositional breadth and intricate detailing.

Commentators rhapsodized, especially noting the artist’s genius as a colorist. “Niagara” toured cities along the East Coast and in Britain, where the work drew praise from influential critic John Ruskin.

Church was now in the top rank of landscape painters, and getting rich. Selling “Niagara” to a collector, he returned to Ecuador to explore and sketch mountains where he conceived another epic image. Unveiled in April 1859 in New York City, “Heart of the Andes” was Church’s most ambitious canvas, approximately 10 feet across and six feet high—a composite view of Ecuador, from distant peaks to exquisitely rendered tiny birds and plant tendrils. The ticket price included use of opera glasses to focus on details. The staging emphasized the composition’s drama: Curtains at either side of a heavy frame and an array of tropical plants Church had brought from South America created the impression of looking out a window into the Andean sublime. Sale of prints from an engraving added to the work’s popularity and commercial success.

In London and across the United States, “Heart of the Andes” received thunderous acclaim, touring for two years. Seeing the painting in St. Louis, Mark

Twain wrote rapturously of its effect on him. The painting’s selling price of $10,000 was unprecedented for a work by a living artist. At 33, Church was America’s most celebrated painter.

Among the spectators lining up in New York to view “Heart of the Andes” was Isabel Carnes, a young beauty from Ohio. Watching spectators view his masterpiece, Church saw Isabel and fell in love. As a friend recalled, the painter described his first sight of her as “A ravishing vision, a star illumined with light never before seen on land or sea!” For Isabel, he painted “Star in the East.” They married in 1861. A few weeks before the wedding, Church purchased 126 acres of farmland across the Hudson from Cedar Grove—on the overlook where years before he and Cole had sketched. The new owner planted orchards, imported trees, and built a clapboard cottage where he and Isabel could raise a family. He worked on plans for a chateau to be built later. He gradually acquired the most scenic parcels of adjoining land, including a wooded hilltop. “Almost an hour this side of Albany is the Center of the World,” Church wrote to sculptor Erastus Dow Palmer. “I own it.” In 1862, son Herbert arrived; daughter Emma, in 1864. In March 1865, the family was in New York City when diphtheria claimed the children. In 1866, Isabel gave birth to Frederic Joseph. That year the young family traveled through Europe—son Theodore Winthrop was born in Rome—and continued to the Middle East, where Byzantine and Arabic architecture fascinated Frederic. The 18-month trip took the Churches to Beirut; he continued alone to the Ottoman Empire cities of Jerusalem, Damascus, and Petra, where stone ruins intrigued him. He shipped home more than 15 crates of artworks and artifacts, along with three white Damascus donkeys.

Returning to his overlook farm, Church scrapped those plans for a chateau. Inspired by his travels, he designed a Persian-style structure with Moorish and Italianate influences. He hired as a consultant landscape architect Calvert Vaux, Frederick Law Olmsted’s collaborator on Central Park.

Vaux and Church were in agreement about enhancing nature’s beauty with design. Vaux assisted Church with transforming more than 200 untamed acres into settings artfully cultivated in the picturesque style.

His piece of property and dwelling occupied Church for the next three decades. Amid widespread disillusionment brought on by the Civil War and its industrialized slaughter, Church’s

artistry fell from favor, his tour-de-force New World romanticism lost

on a public weary of triumphalist nationalism. Art from France’s Barbizon School, a more evocative and intimate style, became the vogue. Adapting to that approach, another Hudson River painter, George Inness, eclipsed Church.

In 1870, disheartened by the public’s indifference and hampered by the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis, Church poured his creative energy into the home he called a “feudal castle” and later named Olana, after a Persian fortress treasure-house pictured in a book Isabel had given him. In hundreds of sketches and watercolors, both imagined and based on architectural pattern books, Church conjured a 500-foot bell tower reigning over stone arches, balconies, bays, ornate cornices, and a long piazza for watching Catskills sunsets. Construction took place largely between 1870 and 1872, with Church adding to and refining Olana for the rest of his life. The interior spaces radiate from a Middle Eastern-style courtyard. Broad arches and tall windows reveal panoramas of the Hudson Valley.

No detail was too minor for Olana’s creator. For the exterior stone and brick, Church created geometric motifs in contrasting colors. He designed the interior stencils and tiles. He custom-mixed colors for complex paint schemes. “I match every stone that is laid, examine every timber, direct everything no matter how trivial,” Church wrote to one of his patrons. He even designed the etched-brass fireplace surround.

Church filled his treasure house with furniture, fabrics, and artifacts he and Isabel collected on their travels and imported from abroad. The couple shared the Victorian vogue for curios: Chinese pictures, mounted birds of paradise, Tiffany glass, brass sculptures, butterflies, and Indian boxes arranged by Church into arresting tableaux.

Church brought the same artistic intensity to the grounds, planting thousands of trees and shrubs and creating meadows, gardens, and a lake. “I can make more and better landscapes in this way than by tampering with canvas and paint in the studio,” he wrote to Palmer. Still painting, though not for exhibition, Church based smaller works on his travels and views from his home. “When autumn fires light up the landscape you will see Nature’s palette set with her most precious and vivid colors,” he wrote to painter Jervis McEntee.

Isabel Church was 62 when she died in 1899. In 1900, after wintering in Mexico, Frederic Church, 63, was in New York City when he died, probably of rheumatoid arthritis. At the time, paintings by Church were selling for less than a tenth of what they once brought. The Metropolitan Museum of Art honored his passing with a small memorial exhibition.

Church left Olana to his youngest son, Louis, 30, who for decades ran the property as a farm. Louis and his wife, Sally, held onto the house’s contents except for donating a substantial number of Frederic Church’s drawings to the Cooper-Hewitt Museum. The childless couple scarcely altered the house or changed its opulent furnishings. Louis died in 1943 but Sally was still living at Olana in 1953 when art history student David Huntington

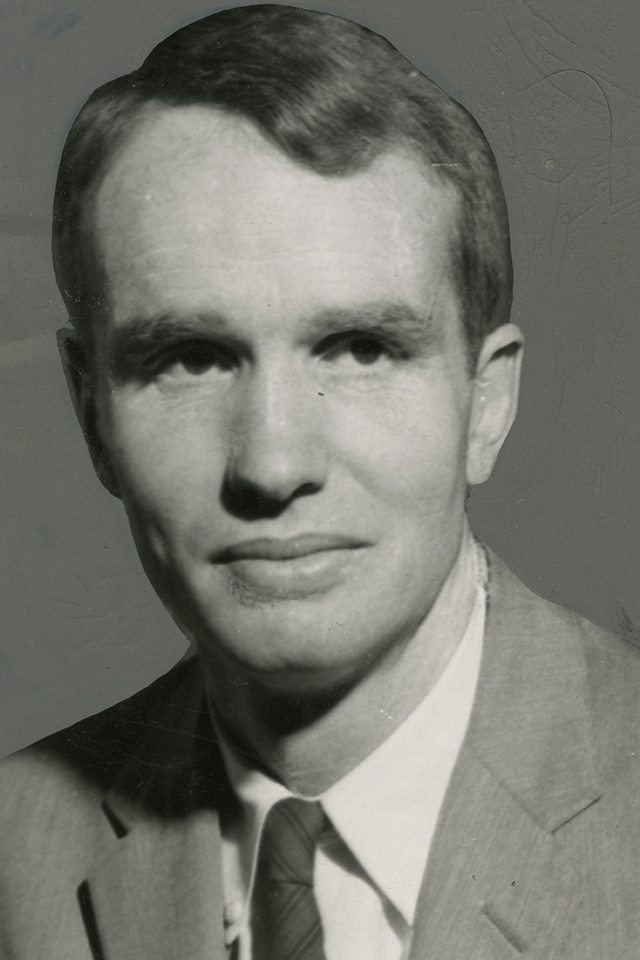

arranged to stop by for a look. After contacting the elderly widow, he got a tour from the couple who handled the estate’s farming. Huntington was writing a dissertation at Yale on an artist who had fallen from fame into obscurity—Frederic Edwin Church.

“I went into the house absolutely bewildered by what I saw, not at all expecting such a relic of the nineteenth century, almost virtually untouched, unchanged,” Huntington told an interviewer in the 1980s.

The Olana attic’s inventory “absolutely staggered” him: paintings by Church and other artists, hundreds of Church drawings and oil studies, and thousands of photographs, along with journals, letters, and other ephemera.

Huntington took up residence in the nearby city of Hudson for four months. When not studying Olana and its contents, he made local acquaintances like lawyer Alexander “Sam” Aldrich. Huntington’s research earned him a doctorate and a reputation as the foremost expert on Church. He became an associate professor of art history at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts.

During the mid-20th century, Olana and other ornate Victorian relics came to be regarded as white elephants, consigned to deterioration and demolition. American paintings were also out of fashion. In autumn 1964, still teaching at Smith, Huntington got a call from a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Sally Church, 96, had died, the curator said, leaving decisions regarding Olana in the hands of her nephew and co-executor, Charles Lark. Fearing Lark might sell the estate, Huntington contacted him. Lark confirmed the professor’s worries. Olana’s likely fate was subdivision of the 250-acre property and its picturesque viewsheds, demolition of the house, and dispersal of Church’s furnishings and collections, including more than 700 paintings.

Huntington asked Lark to let him document the house’s contents. He also sought an option to buy Olana, priced at $470,000, and time to raise that sum. Lark gave Huntington three months’ grace, and the scramble was on. A committee Huntington formed with Sam Aldrich, preservation pioneer James Biddle, and others arranged a leasing agreement to buy more time in order to raise money.

The nonprofit project did not take off running. Church and the Hudson River School had fallen off the radar. The year before, across the river, Cedar Grove had been emptied, its contents auctioned from the porch, erasing Thomas Cole’s presence. Downstream, New York City had demolished the Beaux Arts splendor of Pennsylvania Station. Upriver in Albany, Governor Rockefeller had pushed through a massive—some said monstrous—urban renewal undertaking, the Empire State Plaza, that gutted the state capital’s historic heart. Nationwide, America’s architectural past, from early Dutch domiciles to High Victorian castles, was vanishing under the wrecking ball and the bulldozer.

Huntington and allies bore down. In collaboration with the Smithsonian Institution, the art professor organized an exhibition of Church’s paintings that opened in Washington, DC, in February 1966—the first Church retrospective since that memorial exhibition in 1900. The press chimed in. To headline a lavish 14-page spread, the May 13, 1966, Life magazine asked, “Must This Mansion Be Destroyed?”

New York Times editorials argued to preserve the house. Huntington, who for years had been researching and writing a Church treatise, rushed into print The Landscapes of Frederick Edwin Church: Vision of an American Era. Enthusiasm for Olana developed into a growing chorus ranging from Hudson Valley locals to Manhattan socialites. Former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, who had marched unsuccessfully to preserve Pennsylvania Station, raised money to preserve Church’s home. The exotic pile’s least likely, most powerful ally joined in out of simple kinship. Nelson Rockefeller, genius loci of the Empire State Plaza, was the brother of conservationist—and Olana supporter—Laurance Rockefeller, as well as a cousin of Huntington’s stalwart associate Sam Aldrich.

With a June 30 sale deadline impending, the Olana preservation campaign was $170,000 short. New York Assemblyman Clarence Lane and State Senator Lloyd Newcombe, who represented nearby constituencies, introduced a bill that would authorize the state to acquire Olana. The Lane-Newcombe Act passed unanimously; it couldn’t have hurt that Jackie Kennedy called brother-in-law and U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy (D-NY), asking that he throw in on Olana’s behalf, too.

The Lane-Newcombe bill became law on June 27, 1966, when Governor Rockefeller signed it—the dramatic flourish of his deus ex machina appearance at Olana’s Persian doorway. A year later, Church’s great work became a New York State Historic Site. Ever since, under the Friends of Olana—now the Olana Partnership—the artist’s house, collections, and artworks have been undergoing conservation and study. The late David Huntington’s book revived interest in Church’s artistry. In 1979, the painter’s once-neglected Arctic-themed masterpiece, “The Icebergs,” was auctioned for $2.5 million, at the time the most paid for an American painting. Olana today is the locus of interest in the Hudson River School and the American Romantic movement. In 2016, the house marked 50 years as a public holding, during which more than two million visitors experienced Church’s vision. For the anniversary, the partnership restored the carriage trails, so visitors in electric vehicles could roam lanes where farmers once delighted to glimpse beautiful Isabel Church driving her donkey cart. H