In December 1969 the effort to recover two downed airmen snowballed into the biggest rescue mission of the Vietnam War

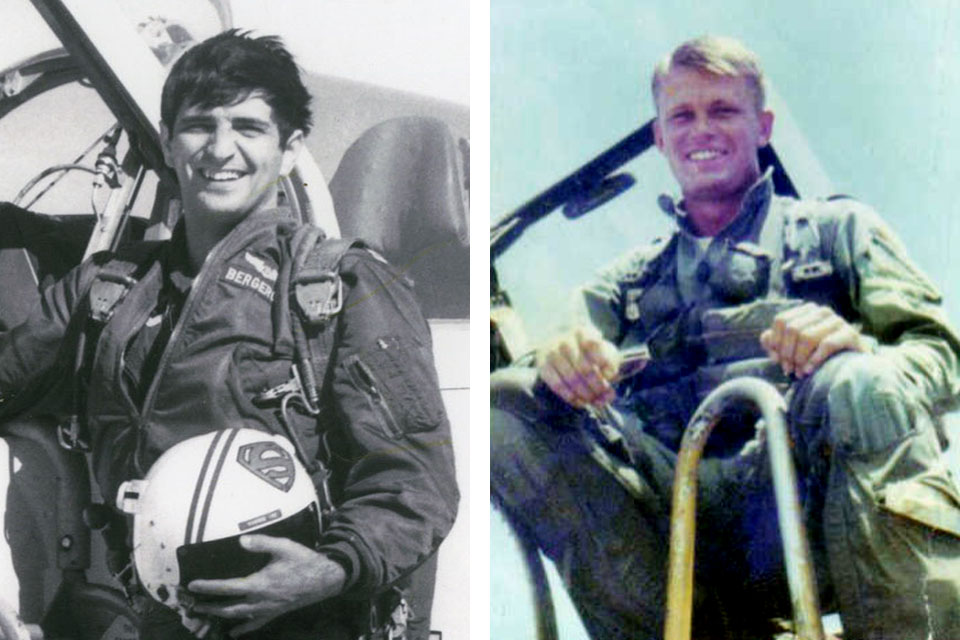

The mission went wrong almost from the start. Two U.S. Air Force F-4C Phantoms of the 558th Tactical Fighter Squadron, call sign “Boxer,” found their primary target weathered over. They diverted north to the village of Ban Phanop, Laos, near a chokepoint where the Ho Chi Minh Trail crossed the Nam Ngo River, to sow the ford with Mk-36 mines—500-pound Mk-82 low-drag bombs with fuses in their tails. In the trailing aircraft, Boxer 22, pilot Capt. Benjamin Danielson and weapons systems officer 1st Lt. Woodrow J. “Woodie” Bergeron Jr. were on their first sortie together. Just after dropping their ordnance, the Phantom suddenly pitched up, then down. Their flight leader called over the radio: “Boxer 22, you’re hit! Eject! Eject! Eject!”

It was Friday morning, Dec. 5, 1969, and Boxer 22 was about to become the objective of the biggest rescue mission of the Vietnam War.

Ejecting, Danielson and Bergeron—Boxer 22 Alpha and Bravo—came down on opposite sides of a dogleg in the Nam Ngo, in a valley a mile across and a thousand feet deep, walled with karst, limestone cliffs. They were just 10 miles from the North Vietnam border, but only about 65 miles east of NKP—Nakhon Phanom Royal Thai Air Base, the main base for U.S. Air Force special operations squadrons specializing in search and rescue.

A-1 Skyraider fighter-bombers scrambled, and a summons went out for HH-3E Jolly Green Giant rescue choppers, fast jets and forward air controllers (spotter planes to direct the attack aircraft). Standard procedure was to find and extract downed airmen before enemy forces concentrated on their position. Unfortunately, the enemy was already concentrated around Ban Phanop.

“Sandy 1, this is Boxer 22 Alpha,” Danielson radioed the first Skyraiders to arrive. “I need help now! I’ve got bad guys only 15 yards away, and they are going to get me soon.”

1st Lt. James G. George, the Skyraider leader, answered the call: “22 Alpha, this is Sandy 1. Keep your head down. We’re in hot with 20 Mike Mike.” Four Skyraiders raked the enemy troops with 20mm cannon fire.

It was as if the entire valley answered back. From his position Bergeron saw the enemy open up with 23, 37 and 57mm anti-aircraft artillery and heavy machine-gun fire from positions in the karst paralleling the river. Evading the fountain of tracer rounds, George informed King 1, the HC-130 Hercules airborne command post orbiting 24,000 feet above Laos, “We are going to need everything you can get a hold of.”

Word of the Boxer 22 shootdown had already been passed up the chain of command to 7th Air Force headquarters at Tan Son Nhut air base near Saigon and from there to “Pentagon East,” U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. From all over Indochina, American air power converged on Ban Phanop: F-100 Super Sabres, F-105 Thunderchiefs, Navy A-6 Intruders, more Phantoms and more Skyraiders—guns and bombs, rockets and napalm to pound those enemy guns into submission.

George assured Bergeron and Danielson, “We’re going to lay CBU [cluster bomb units] all around you, and then we are going to bring in the choppers in to scarf you up and we’ll all go home for a beer.” But he urged two Jolly Greens standing by five miles to the west to move fast: “Let’s get this done. I don’t think we can waste any time.”

At 12:40 p.m. Capt. Charles Hoilman took JG-37 in for the rescue. His crew reported an increasing trail of flak following the chopper as it approached the pickup point. The moment they slowed to a hover over Danielson’s position, the Jolly Green became a big, stationary target, and the enemy brought every gun to bear. With the fuselage riddled and the turbines overheating, Hoilman climbed out to the northeast. “I’ve got to go home,” he radioed. “I’ve burned the shit out of these engines.”

In retaliation, Skyraiders saturated the cliffs with napalm and the valley with tear gas. But when JG-09 arrived, the enemy fired small arms and two 23 mm cannons from the karst caves, driving it off with a transmission leak, hot temps and malfunctioning controls. Less than two hours in, the rescue had turned into a pitched battle.

The Americans called in new HH-53E Super Jolly Greens—bigger, more powerful, better armed and armored. The Skyraiders dropped cluster bombs and fired 20 mm shells to within 100 feet of JG-76, remembered pilot Capt. Holly G. Bell: “It sounded like we were caught in a popcorn machine.”

As Bell’s chopper swung in over Danielson, tail gunner Airman 1st Class David Davison hosed half the valley with a red stream of tracer fire at 4,000 rounds per minute, but he was outgunned. The helicopter received multiple shots to the fuselage and rotor system and began to vibrate hard. “I knew if we took more hits, my Jolly would be shot down,” Bell later reported. “During egress from the valley, I received notification that Davison had been badly hit.” Struck in the head, the airman would be posthumously awarded the Silver Star. (Two months later, Bell and his entire crew would be shot down and killed during another search and rescue operation.)

By now the enemy game plan was obvious: Hole up while the Skyraiders and jets did their worst, and then, when the rescue choppers came in, emerge from cover and let them have it. A burst of fire cut a hydraulic line in JG-69, piloted by Capt. Jerald Brown. The spraying fluid caught a spark, and the helicopter climbed away gushing flames.

An enemy 37mm shell blew a two-by-four-foot hole in the belly of Maj. Jerry Crupper’s JG-79. Hovering in JG-68, Maj. Hubert Berthold remembered seeing “the entire area lit up with tracers from both sides, from both the karst and the ground.” His chopper took fire a full five miles west of the crash site. The crews were lucky to survive.

Skyraider pilot Col. Daryle Tripp, deputy commander of operations of the 56th Special Operations Wing, told everyone: “We have at least 45 minutes to sunset. We will make at least one other attempt. But it’s fairly apparent from the gunfire out here that I just saw that there is still more work to be done.”

Capt. Donald Carty got his JG-72 to within 30 feet of Danielson before being driven off. “We were so low and it was so dark on the egress that we almost hit the karst,” he said. “I advised against making another attempt because it was too dark and our mini-guns were either jammed or out of ammo.”

Ninety aircraft had dropped almost 350 bombs and rockets on the Nam Ngo valley, but as night fell the enemy was still there and its tracers rounds streamed up for the Americans. “The AAA was firing above us across the entire valley, with the tracers ricocheting off the side of the karst on the opposite side,” recalled a low-flying Skyraider pilot. “It was like being in the bottom of a tunnel of fire.”

Five of seven helicopters that had taken serious hits were unlikely to be repaired by morning, and it was unclear if the remaining two would ever fly again. Commander Tripp broke the news to the Boxer 22 crew: “We have run out of helicopters, and I want you to bed down. Try to get yourself dug in, and we will be out here first thing in the morning.”

“Good night, see you in the morning,” Bergeron replied. He decided to stay where he was and “just dug deeper in the foliage and debris I was hiding in.” Bergeron and Danielson kept in touch with their survival radios. “Neither of us slept that night.”

At Nakhon Phanom air base, ground crews worked into the morning to have their birds ready by dawn. The 7th Air Force commander, Gen. George S. Brown, informed the Pacific Air Forces command and the top military commanders in Saigon that all aircraft in theater, except those supporting troops in direct enemy contact, would be used in the rescue effort. As of sunup, virtually the entire air war above Southeast Asia was to be fought over Boxer 22.

Meanwhile, Bergeron had a front-seat view of the enemy supply convoys crossing the Nam Ngo a quarter-mile to the north. “I’d sit and count the trucks, and I learned how they got the trucks across the ford. They’d hold up flashlights one way to start the winch, another way to pull the truck across, and another way to stop it.”

But the North Vietnamese knew he and Danielson were still out there. “I could hear the enemy looking for Ben,” Bergeron said. “They would go to a clump of trees or other spots where he might be hiding and fire off a few AK-47 rounds. No one came looking for me.”

On Saturday, Tripp resumed command over Ban Phanop at 6 a.m. They were still organizing the aircraft for a rescue attempt when Bergeron reported that the North Vietnamese had just killed Danielson. “They were talking in a fairly normal tone, and then all of a sudden they started yelling, like they found him. They shot a very long burst of AK-47 bullets. I heard Ben scream. It was definitely him. I knew that he had been killed.”

There was no time to mourn. Enemy troops were already wading the river toward Bergeron’s position. “I decided they weren’t taking prisoners. If they came over to where I was hiding, I was going to try to fight it out with my pistol.” He called in Skyraiders and Phantoms to strafe the river with 20mm fire, and the soldiers “physically disappeared.”

Aircraft streamed down one after another through the narrow valley. On cross routes, Phantoms targeted the gun caves with AGM-12c Bullpup air-to-ground missiles, AGM-62 Walleye glide bombs and 2,000-pound laser-guided Paveway smart bombs. “Watch out for midair collisions with the Skyraiders raking the valley floor underneath you,” Tripp warned, “and check the big AAA guns on the tops of the east karsts as you pull off.”

The big 2,000-pounders homed in right over Bergeron’s head. He remembered, “When the Paveways would hit, it would physically throw me in the air about two inches—a beautiful feeling.” As the valley filled with smoke, gas and dust, the guided weapons had trouble locking onto their targets, but they only had to get close. When Bergeron saw a Paveway hit halfway up the cliff wall above a gun site, “the explosion literally just dumped the mountain down on top of them,” he said.

For five hours the valley was cluster-bombed, napalmed, rocketed and shot up, with ordnance hitting dangerously near Bergeron’s position. “The closest they came to me with 20mm cannon fire was about 1 foot,” he recalled. A tear gas bomblet actually bounced off his chest; one whiff was enough to make him “urinate and retch all at the same time,” he said. “Physically and mentally you can’t control yourself.” (In 1993 an international treaty banned the use of tear gas in warfare.)

The Skyraiders’ smoke corridor—two banks of gas and white phosphorus—was so massive it was visible from space, as recorded by a Nimbus III weather satellite shortly before noon. Pilots could see the smoke from Nakhon Phanom, 65 miles away. “At 5,000 feet, it looked like a Texas sandstorm,” a Skyraider pilot remembered. The airstrikes were so heavy that the 7th Air Force began running low on smoke bombs.

Down in the acrid haze, visibility dropped to near zero. Jolly Greens made six rescue attempts, but whenever the air over the Nam Ngo valley wasn’t thick with smoke, it was full of bullets. As soon as the choppers came to a hover over Bergeron—one so low that its rotors clipped the trees—their wash swept everything clear, and the enemy gunners found them.

At 6 p.m. the day’s last rescue attempt failed. Night fell, the American planes drew off, and the North Vietnamese closed in. “I knew that the enemy was aware I was hiding somewhere on the bank of the river,” Bergeron said, “and it was just a matter of time until they found me.” About 15 minutes after dark, three enemy soldiers emerged from cover, tossed a tear gas bomblet into his bamboo thicket and sprayed it with AK-47 rifle fire. All they found was his survival gear. Bergeron had moved 40 feet to the north and was hiding under exposed tree roots. In the scramble, though, he had lost his .38-caliber revolver. “If those guys had a flashlight,” he realized, “they could have found me.”

Before the last Skyraider departed, its pilot had advised, “If the river is deep enough, get in it and go downstream.” When no enemy troops were in sight, Bergeron waded in, but was too worn out to swim. He dragged himself to a bush overhanging the bank and got under it. Lying there in the darkness, exhausted and hungry, listening to enemy trucks rolling past on both sides of the river, he drifted in and out: “During the night I began to hallucinate. I envisioned two members of my squadron were with me, discussing my plans of action.”

At Nakhon Phanom, nobody was giving up. The ramps and taxiways were jammed with aircraft being repaired, refueled and reloaded, as all hands worked to get them patched up and ready for another go in the morning.

After nearly 48 hours in enemy territory, Bergeron was on his last legs: “I was drinking water out of the river and had only a little food.” Finally, at 5:15 a.m., the lead Skyraider picked him up on radio and asked him to authenticate. “What’s your best friend’s name?”

He replied, “Weisdorfer.”

The Skyraider pilot had to laugh. “I don’t even have time to check it, but it’s gotta be you.” By 6:30 a.m., the valley was under renewed attack. American aircraft forced the enemy gunners to take cover and laid a fresh smoke corridor. Lt. Col. Clifton Shipman took HH-53 JG-77 down for the pickup and was immediately submerged in smoke. “When we got down on the river,” he reported, “we could see absolutely nothing.” But the enemy could see them. The helicopter took fire from a camouflaged truck, and Shipman spotted an estimated 500 to 1,000 troops to the northwest, massing for an attack.

During the past two days, Skyraider leader Maj. Tom Dayton of the 22nd Special Operations Squadron had flown four separate helicopter escort missions, only to see 15 rescue attempts fail. Now he ordered the Skyraiders into two rotating “daisy chain” formations on either side of Bergeron’s position, 10 to the west and 12 to the east, circling like a pair of gears to grind the enemy with smoke, gas and cannon fire. The truck gun was quickly silenced. The valley was sanitized and saturated with smoke. Shipman refueled JG-77 in midair, and his gunners topped off their mini-guns. Everybody was ready for another try. Dayton gave the go-ahead at 11:40 a.m.

Coming from the east, Shipman’s crew couldn’t spot Bergeron. Dayton, flying overhead, talked them in. “They flew over me,” Bergeron remembered, “did a 360-degree turn” and then lowered the penetrator, a bullet-shaped, anchor-like rescue hoist with spring-loaded flip-out seats. After days of popping smoke and flares, the only thing left that Bergeron could signal with was his vinyl escape chart, a scale map of enemy territory. He bolted from his hole waving the chart’s white side. “The penetrator landed about 4 feet away from me in the water,” Bergeron said. “I put the strap on first and then flung the penetrator beneath me.”

Meanwhile, Shipman’s tail gunner was hosing his mini-gun at 20 to 30 enemy soldiers just 50 feet away; the left-side gunner was spraying troops across the river. The crew dragged Bergeron aboard and the Jolly Green powered upward. “We’ve got him,” Shipman announced, “and we’re coming out!”

Every radio over Ban Phanop promptly jammed with cheers. Dayton (who was awarded the Air Force Cross, just below the Medal of Honor in valor awards) ordered everybody home. Over Nakhon Phanom the Jolly Greens streamed red smoke from their tail ramps in victory. Every ground crewman, air crewman and the entire command staff crowded around Shipman’s aircraft, and Bergeron emerged to roaring applause.

Bergeron was awarded the Silver Star for his intelligence of enemy operations at the Nam Ngo ford and after the war flew A-10 Thunderbolt II attack jets, retiring in 1987 as a lieutenant colonel.

The rescue of Boxer 22 was the largest search and rescue mission of the Vietnam War. A total of 336 sorties were flown by aircraft that expended 1,463 smart bombs, high-explosive bombs, cluster bombs, smoke bombs, napalm bombs and rocket pods over the course of three days. Skyraiders alone flew 242 sorties; the HH-3 and HH-53 helicopters, over 40. Five Skyraiders were damaged, but the Jolly Greens got the worst of it. Five of the 10 involved never flew again.

In 2003 a Laotian fisherman discovered human remains, a partial survival vest, a survival knife and Danielson’s dog tags along the banks of the Nam Ngo. On June 15, 2007, Lt. Cmdr. Brian Danielson of U.S. Navy Electronic Attack Squadron 129—18 months old when his father was shot down—laid his father to rest in his hometown, Kenyon, Minnesota. At the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., Danielson and JG-76 tail gunner Dave Davison are remembered next to each other on panel 15W, lines 26 and 27. ✯

Don Hollway thanks Woodie Bergeron and retired Maj. Gen. Daryle Tripp for their help in telling this story. For more information, photos and audio, visit donhollway.com/boxer22.