On San Juan Hill, a boyhood tenderfoot became a war hero

BY MID-MORNING on July 1, 1898, sniper fire from the hills to the north had forced Laughing Horse to dismount from Little Texas, his favorite horse. Hunkering in the tall grass on a rise identified by maps as Kettle Hill, the warrior leader peeked now and then, studying the terrain ahead through thick spectacles. Sioux among his soldiers had dubbed their boss Laughing Horse for the unusually large teeth he exposed when he laughed, which was often.

At the moment, though, Laughing Horse, better known as Theodore Roosevelt, was not laughing. He had orders only to support an initial attack on Spanish troops holding the San Juan Heights that lay east of Santiago de Cuba, a port in eastern Cuba, but the situation was growing fraught. Roosevelt, a colonel in the U.S. Army, commanded the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry regiment. Formerly New York City’s police commissioner, Roosevelt, 39, and his men were part of an American force attempting to capture Santiago de Cuba, in whose harbor the Spanish war fleet was riding at anchor.

The violence on the heights overlooking Santiago de Cuba had its origins in the third attempt by inhabitants of Cuba to throw off Spanish rule, a revolt smashed by Spanish troops engaging in torture and confining civilians in concentration camps. American publisher William Randolph Hearst undertook to help the Cubans—and boost newspaper circulation–by publicizing these and other Spanish transgressions.

Hearst sent reporters and artists to the island. His papers’ highly exaggerated coverage spurred President William McKinley to demand that Spain reform its behavior in Cuba. When in response pro-Spanish gangs in Havana rioted against Americans, McKinley ordered the battleship USS Maine from Key West, Florida, to Havana Harbor, where on February 15, 1898, the warship exploded, killing 260 sailors. Hearst papers and the American public blamed Spanish authorities, and the United States went to war against Spain.

Upon landing as part of an American expeditionary force 20 days earlier, Roosevelt and his men had hacked inland through coastal jungles near Santiago de Cuba to a landscape of savanna and patchwork clearings carved out for planting sugar cane. For the past day, the unit had been traversing intense undergrowth and forests at the base of the San Juan Heights. Rising in a distant purple haze were the Sierra Maestra, a mountain range blocking Cuba’s cooling northeast breezes.

No courier had come from U.S. Army headquarters with orders to advance. Roosevelt had hoped that once his outfit left the jungle the lack of cover would discourage the Spanish from sniping, but on these grasslands, his soldiers were the ones losing heart, exposed as they were to merciless rifle fire.

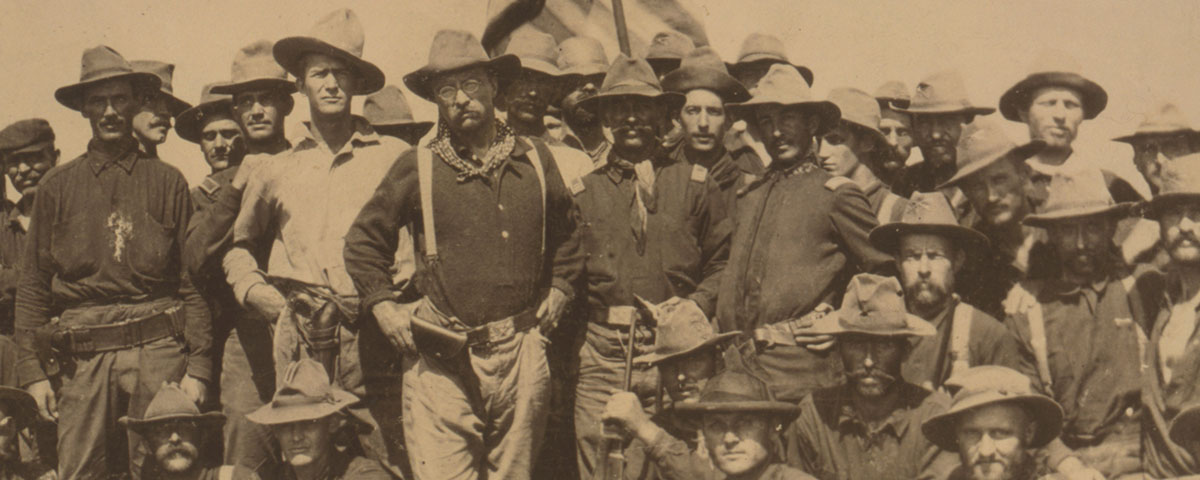

Roosevelt was leading an odd lot of characters. The colonel had recruited or welcomed into the ranks leathery, bowlegged cowboys from Oklahoma and New Mexico, Wild West lawmen like Bucky O’Neill, Native Americans, some in war paint, and others, such as Harvard football quarterback Dudley Dean, American tennis champ Bob Wrenn, and Joseph Sampson Stevens, the world’s greatest polo player. Portly artist Frederic Remington was there, along with Zeta Sigma fraternity member-turned-cavalryman Frank Knox. Stephen Crane, a young journalist and writer, had come, covering the war for the New York World. Natty in white tropical suit and matching pith helmet, another, better-known war correspondent, Richard Harding Davis, was on hand.

The press, enthusiastic fans of the ebullient Roosevelt, had dubbed him and his men “Rough Riders,” a nom de guerre borrowed from placards advertising professional plainsman William F. Cody’s Wild West show. Author of a number of scholarly books, Roosevelt had been an avid boyhood naturalist. At 26, after Valentine’s Day, 1884, when wife Alice and mother Mittie both died, he went west, buying a ranch in North Dakota, working cattle and even hunting rustlers.

San Juan Heights begged to be controlled, as the Spanish now did. From that elevation, artillerymen could draw beads on Santiago Harbor. If those guns were American, their rounds would chase Spain’s fleet out to where the U.S. Navy waited. General William Shafter, the U.S. Army ground forces commander, had landed 15,000 men. However, at the foot of the hills that day, Shafter had deployed only 8,400 regulars, along with 3,000 Cuban insurgents. Aiming down from the Heights at the attackers were 800 Spanish soldiers commanded by Arsenio Linares y Pombo. In Santiago, Linares had 10,000 men in reserve.

For cannon, the Americans had brought obsolete 3.2-inch black-powder artillery pieces that lacked the range to hit the Spanish lines. To compensate, the expeditionary force formed a detachment of swivel-mount Gatling guns—hand-cranked Civil War-era relics that the troops called “coffee grinders.”

Under Lieutenant John Parker, three four-man Gatling crews, each with a 10-barrel gun, were to roam the battlefield giving support. Shafter placed one Gatling and crew at his rear-area command tent.

The Gatlings were mounted on carts pulled by mules, but had proven difficult to maneuver and often bogged down. Parker had moved the three guns and their crews to front and center in the American line, just to Roosevelt’s left. Ahead, on Kettle and San Juan hills, Spanish troops were deploying smokeless Mauser rifles, augmented by modern Maxim machine guns.

Besides Cuba, Spain had holdings in Africa, Asia, and the Pacific. In North America, Spain had Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Spanish Virgin Islands. America’s Indian wars had led the Spanish and other Europeans to think the U.S. Army only knew how to fight indigenes. As if trying to live down to Continental expectations, the U.S. Army issued the force that was being sent to tropical Cuba wool uniforms. The men itching in those heavy getups carried black-powder Springfield rifles that gave off puffs of smoke when fired, revealing marksmen’s positions. The Navy had hauled the invasion force and its mounts to Cuba without having a way to deliver horses to land. Pushed from transports in hopes they would swim ashore, many Army mounts drowned. Equipment crates bore no markings; to identify and direct materiel, quartermasters had to open every single box. Cuba was rife with tropical diseases; Army chiefs feared that in a prolonged fight sickness would claim more soldiers than bullets.

However, the Americans had caught a break. When Spanish commander Linares seized San Juan Heights, he failed to fortify the hillside’s crest—not the physical hilltop, but the point downslope from which gunners would have a clear perspective on the terrain the enemy had to ascend. Linares instead had ordered his men to the highest point, from which soldiers could not necessarily see and respond to actions downhill. But Spanish snipers still had the advantage, picking at 560 Rough Riders trying to stay alive in the tall grass. To boost morale, O’Neill, the Arizona lawman, stood and strolled in front of his men smoking a cigarette.

“Captain, a bullet is sure to kill you!” one shouted.

“Sergeant, the Spanish bullet ain’t made that will kill me,” O’Neill replied, whereupon a bullet killed him, passing through his mouth and then the back of his head.

Roosevelt had had enough. Summoning a courier, the colonel scribbled a request to his superior, General Samuel Sumner, for permission to advance out of the kill zone. Roosevelt handed the courier the note. Standing to salute, the soldier, hit by a sniper’s bullet, fell dead across Roosevelt. Another man stepped up.

Sumner received Roosevelt’s request a little after noon. “Move forward and support regulars in the assaults on the hills in front,” the general replied. Reading this sentence, Roosevelt, carrying a reconditioned pistol from the USS Maine his brother-in-law had given him, mounted Little Texas and waved his men forward. The Rough Riders stayed put, hugging the ground.

“Are you afraid to stand up when I am on horseback?” Roosevelt shouted.

One soldier stood and, as quickly, was shot. Roosevelt spurred Little Texas. Men behind him began to creep forward. A captain with the Third Cavalry blocked Roosevelt’s way, saying the Third had no orders to charge. “Then let my men through, sir!” Roosevelt barked. He took off his hat and waved it. “Charge the hill!” he cried.

Standing among the 10th Cavalry, composed of African-Americans known as Buffalo Soldiers, their officer, Lieutenant Jules Ord, also decided to press ahead.

As the Rough Riders massed, Ord, son of the late E.O.C. Ord, a Union general during the Civil War, approached his commander, General Hamilton Hawkins.

“General, if you will order a charge, I will lead it,” Ord said. Hawkins made no reply.

“If you do not wish to order a charge, General, I should like to volunteer,” Ord said. “We can’t stay here, can we?”

“I would not ask any man to volunteer,” Hawkins replied.

“I only ask you not to refuse permission,” begged Ord.

“I will not ask for volunteers. I will not give permission and I will not refuse it,” Hawkins said. “God bless you and good luck!”

As Ord ordered his own D Troop forward, he charged, pistol in one hand and saber in the other, joined by Captain John Bigalow and Lieutenant John Pershing. Soon the entire 10th Cavalry had joined the assault. Ord and his men had to cover 400 yards to reach the top of Kettle Hill and from there advance 300 yards more to achieve San Juan Hill, amid murderously effective machine-gun and rifle fire from the Spanish troops’ modern weapons.

From the center of the American line, Parker, the Gatling unit commander, could see Americans climbing Kettle Hill under Spanish fire. Parker ordered his three Gatlings to rake the hilltop. For eight minutes, the gunners suppressed enemy activity, laying down a remarkable 700 rounds per weapon per minute. Reporter Davis feared the American attack lacked critical mass. “One’s instincts was to call them back,” he wrote. “You felt that someone had blundered and that these few men were blindly following some madman’s mad order.”

Reporter Stephen Crane was standing in a grove of trees east of the battle line. He looked up to see the Rough Riders gaining momentum. “By God, there go our boys up the hill!” Crane thought. The unexpected advance stunned foreign military observers. “It’s plucky you know! By God, it is plucky!” a British officer yelled to Crane. “But they can’t do it!”

Two barbed-wire fences ringed the top of Kettle Hill. Bigalow was trying, barehanded, to breach the first when a corporal pushed him aside, slashing at the wire with his bayonet and enabling Rough Riders and Buffalo Soldiers to rush toward the hilltop, 150 yards up. Hit four times, Bigalow fell, severely wounded. Pershing took command, leading the 10th on.

A Spanish bullet to the head killed Rough Rider Roy Cashion, 18. Shrapnel struck Sergeant Charles Karsten, who kept firing until his arm went numb. Remington, whose art celebrated manly violence, hugged the earth. Ahead of the rest, Little Texas galloped Roosevelt to the upper barbed fence, 40 feet from Kettle Hill’s crest. The colonel was cutting wire when a Spanish round struck his left elbow.

Even so, Roosevelt parted the wire, and he and orderly Henry Bardshar stepped through. Two Spanish soldiers stood, aiming; Bardshar shot both. The colonel drew his pistol from the Maine, and from 10 yards doubled over a Spanish soldier “neatly as a jackrabbit,” Roosevelt said later. Roosevelt and Bardshar thought they were the only Americans atop Kettle Hill, but they had not seen Buffalo Soldier George Berry hoist dropped American colors and race unarmed to the hilltop shouting, “Rally on the flag, boys!”

In Kettle Hill’s trenches, Rough Riders and Buffalo Soldiers fought Spanish troops hand-to-hand as Rough Rider Thomas Rynning waved his unit’s flag, signaling that Americans had taken the crest. The Spanish fled, with Buffalo Soldiers, cowboys, Easterners, and Native Americans filling the void. Roosevelt, Pershing, and Ord saw with shock that their improvised charge had ignited an American surge all along the Heights. Linares had kept his 10,000-man reserve in the lowlands rather than reinforcing the Heights, but from blockhouses up San Juan Hill those men that he did have in place were savaging American and Cuban troops with well-directed fire. In response, Parker focused his Gatlings on the enemy trenches on San Juan Heights. The American line slowly advanced. Roosevelt started down Kettle Hill but 100 yards along realized he had with him only five of his men. Two of those fell wounded as he ran back to motivate laggards with a stream of invective. “We didn’t hear you,” men replied to Roosevelt’s barrage of curses. “We didn’t see you go, Colonel!” Now, however, the soldiers rose and followed Laughing Horse on the day’s second mad charge. With the Rough Riders came Ord and Pershing and the men of the 10th Cavalry, all merging into a massive wave. Rough Rider Frank Knox was running hard, screaming, when he realized his was the only white face among a knot of Buffalo Soldiers swarming up San Juan Hill. “I never knew braver men anywhere,” Knox said. Ord, first to the top of San Juan Hill, was shouting orders as his men were catching up when a bullet to the face killed him. Pershing, Roosevelt and the Rough Riders, the 10th, and fragments of other units converged on the crest, where dead and dying men littered Spanish trenches.

Below and to the west, Roosevelt could see Santiago Harbor. A courier brought him orders from angry superiors convinced he had left his previous position without permission: get your men back to Kettle Hill to prepare for a Spanish counterattack, the bosses demanded. In his enthusiasm to join the final assault on San Juan Hill, Roosevelt had led his men off Kettle Hill, leaving a gap in the American lines Linares might exploit. Roosevelt hurriedly shepherded his men back to Kettle Hill, but the Spanish commander had already seen the hole and assigned 600 men to retake that elevation from the Rough Riders.

Using mules, Parker’s gun crews manhandled two Gatlings into position atop San Juan Hill in case of a counterattack. Parker’s superiors ordered one Gatling to Kettle Hill, but before that could take place Linares counterattacked San Juan Hill. The Americans quickly repulsed that sally, a diversion meant to pull away American personnel and attention so Spanish troops could take back Kettle Hill. Seeing this maneuver from the Heights, Parker ordered continuous and devastating fire on the 600. Only 40 counterattackers survived. Sniping and infiltration persisted through the night, but by dawn the Spanish had retreated to Santiago de Cuba. On July 4, the Spanish fleet sailed out of Santiago Harbor to engage the U.S. Navy, which sank every enemy vessel.

By 3 p.m., San Juan Hill was in American hands. The shooting was dying down. Remington, the artist of the Wild West, finally stood to take stock of the battlefield. Bodies dotted Kettle and San Juan hills, many wearing the signature Rough Rider scarf. The 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry’s casualty rate that day was 37 percent, the highest of any American regiment during the war.

Jack Pershing survived. He considered himself lucky. American casualty reports for the battle ranged from 665 to 1,071 dead, and for each battle casualty in the war, disease claimed 134 men. Pershing rose rapidly in the Army, pursuing Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa in 1916 and, during WWI, commanding the American Expeditionary Force in Europe. Within two years of the battle, Stephen Crane died, made more famous posthumously than in life by his fiction and non-fiction. Frank Knox amassed a fortune publishing newspapers and won the Republican nomination for vice president in 1936. He served as secretary of the navy under President Franklin Roosevelt during World War II. The Army nominated Colonel Theodore Roosevelt for a Medal of Honor. That decoration was not awarded until 2001, but within four months of the battle Roosevelt was elected governor of New York. Within three years, he was vice president of the United States, in 1901 replacing the assassinated William McKinley in the White House. On those two hills outside Santiago, Cuba maintains a walking park that honors the men who participated in the Spanish-Cuban-American War’s bloodiest battle. Plaques dedicated by name to Cuban and American units, including the Rough Riders, dot those groomed acres.