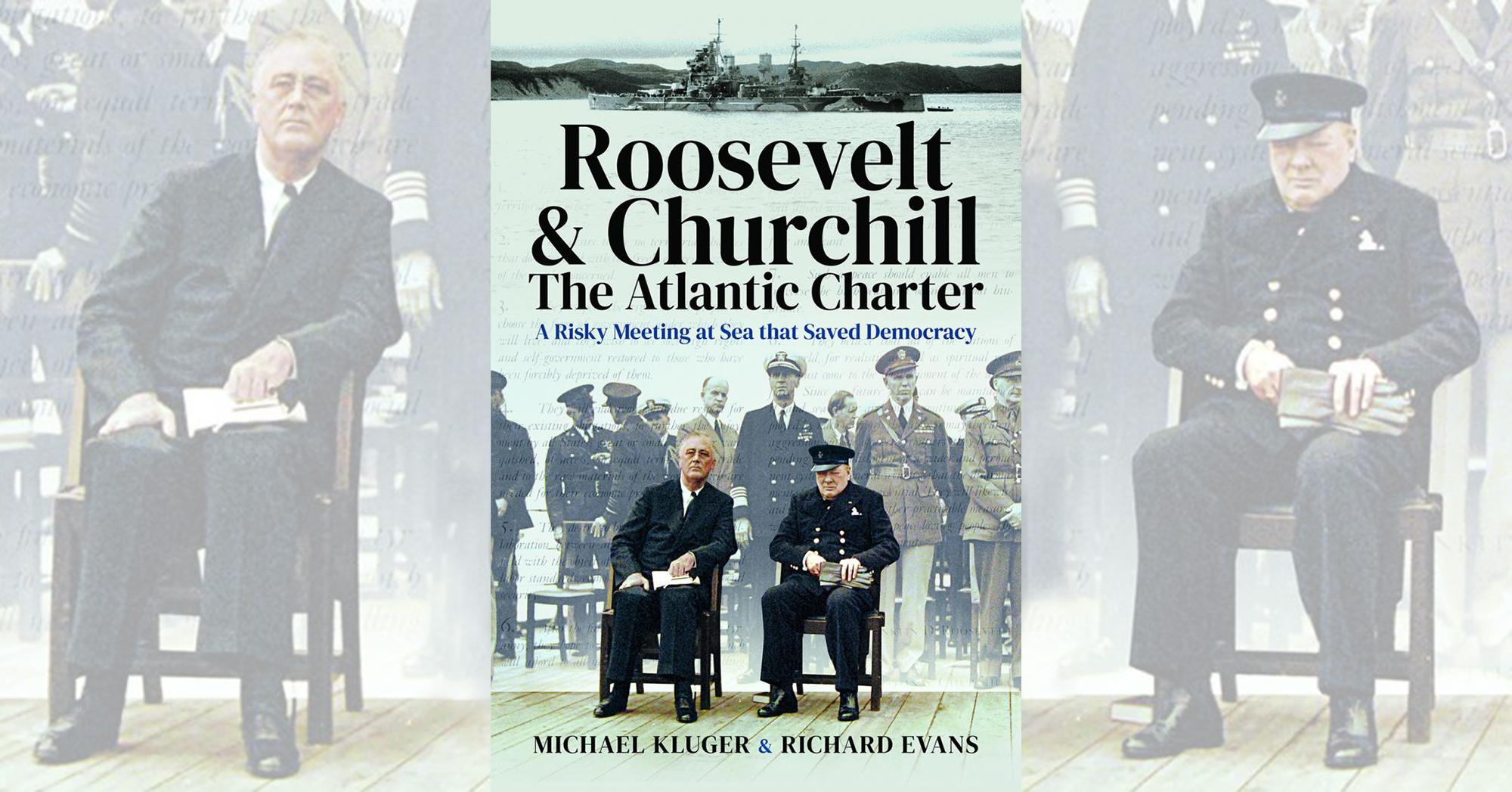

Roosevelt and Churchill: The Atlantic Charter—A Risky Meeting at Sea That Saved Democracy, by Michael Kluger and Richard Evans, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 2021, $37.95

On Aug. 9, 1941, Winston Churchill, the pugnacious prime minister of embattled Britain, sailed into Placentia Bay off the coast of Newfoundland aboard HMS Prince of Wales to secretly meet with U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt aboard USS Augusta. The resulting eight-point Atlantic Charter—advocating freedom of the seas and all peoples’ right to self-determination, among other points—set moral standards for the postwar world order.

British military veteran and war correspondent Richard Evans and academically trained American businessman Michael Kluger examine that defining moment of the “Special Relationship,” arguing that historians have underestimated the risks Churchill took in crossing the U-boat infested Atlantic Ocean for the critical meeting. At that point, however, the United States was the only nation in the world in a position to assist Britain. The four-day meeting resulted in a charter of agreed principles, largely written by Churchill, and fostered trust between the Allied leaders as they led the crusade to destroy fascism.

After sharing the story of how Churchill and Roosevelt got to their respective positions and then recounting their meeting, the authors devote the remaining chapters to profiling supporting actors who made the accord possible. These include presidential adviser Harry Hopkins; U.S. Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall; Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles; British cabinet minister Max Aitken, Baron Beaverbrook; Air Chief Marshal Wilfrid Freeman; and diplomat Sir Alexander Cadogan. Finally comes an odd chapter on Churchill’s son, Randolph, relating how the brilliant but troubled young man served his father as a key counselor.

The authors support their narrative with endnotes, a bibliography and 14 photographs. There are mistakes, such as speculation about a potential meeting between Churchill and Theodore Roosevelt in Cuba in 1898, when the former only visited the island once in 1895. Regardless, the authors’ prose is often eloquent. Deeming Churchill the “most dominant and extraordinary personality the world has seen,” they express hope the charter’s vision will act as a counter to the types of militaristic populism that “endanger the tenets of decency.”

—William John Shepherd

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.