One of Germany’s most famous military commanders met an inescapable death sentence—not by the hands of the enemy, but by the leaders of his own country. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, 52, was forced to commit suicide near the scenic village of Herrlingen on Oct. 14, 1944.

“To die at the hands of one’s own people is hard,” Rommel told his 15-year-old son Manfred minutes before he left their house for the last time. “But the house is surrounded and Hitler is charging me with high treason.”

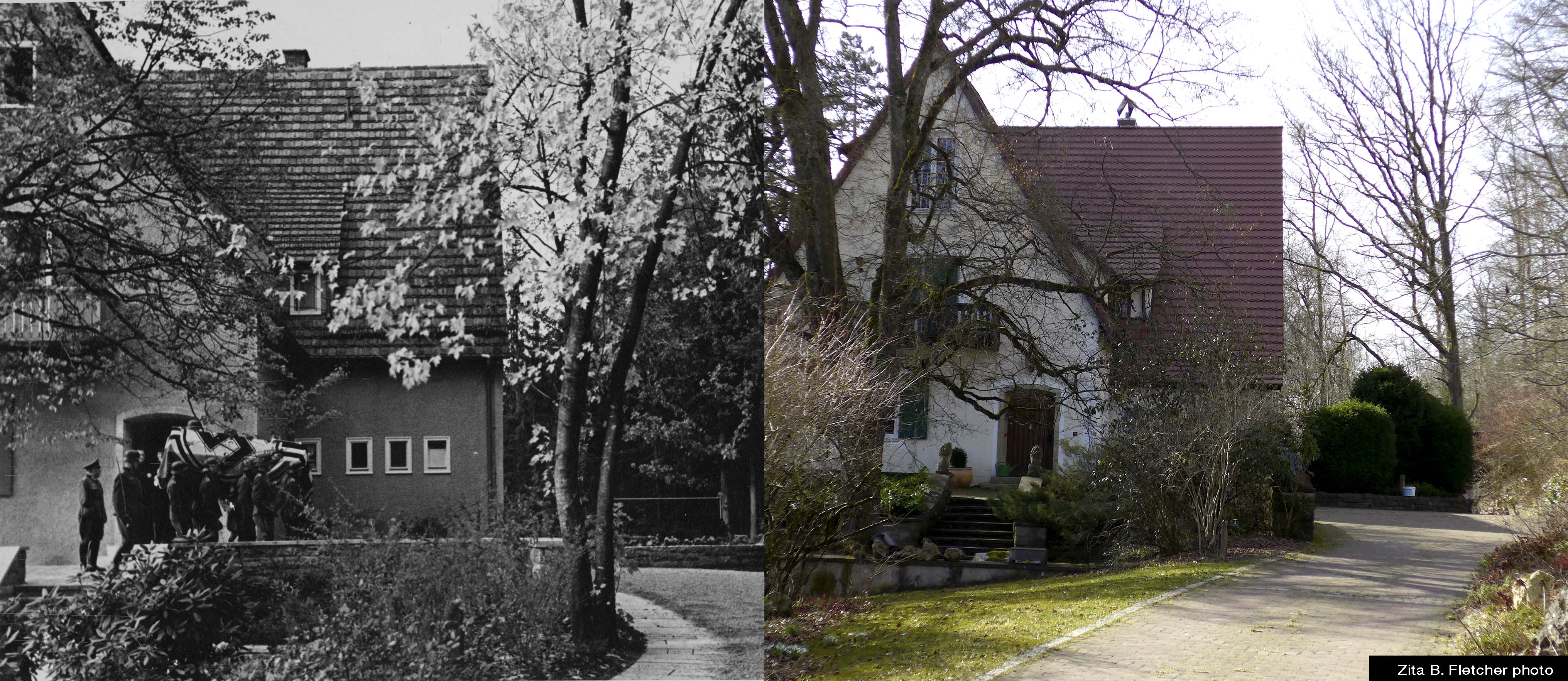

The peaceful town, Herrlingen, located in a rugged and hilly region known as the Swabian Alps, was a place Rommel had been familiar with since boyhood. In the hopes of keeping his family safe from Allied bombing, Rommel chose this out-of-the-way spot as a refuge for his wife and son.

Herrlingen became Rommel’s “home base” during the last year of his life. Sensing an imminent threat from Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime, yet wishing to avoid capture by the Allies, Rommel holed up in Herrlingen and refused to leave the area.

The location of Rommel’s house along a public village road and the presence of nosy locals kept Nazi police at bay—but only for a short time. Throughout summer and early fall of 1944, Gestapo agents and SS plainclothes officers infiltrated Herrlingen. The remote town became a death trap.

OPPOSITION TO HITLER

The Nazis wanted to get rid of Rommel because of his opposition to Hitler—and his concrete plan to overthrow their reign. According to Lt. Gen. Fritz Bayerlein, Rommel and his chief of staff, Hans Speidel, had developed a plan to allow the Allies unopposed access to certain key regions of Germany and to contact Allied leaders for a separate peace. Before this plan had a chance to develop further, an unknown German betrayed Rommel to the Nazis. This informant remains unidentified. Possibilities have given rise to much speculation. Most historians agree that Rommel’s name “came up” during the reign of terror and interrogations following the failed July 20 assassination plot against Hitler in 1944.

However, the exact details of the accusations against Rommel—and who betrayed him—remain shrouded in mystery.

Despite these ambiguities, it was already well-known among Rommel’s inner circle by 1944 that he was bitterly disillusioned with Hitler. Rommel allegedly remarked to family and friends after the July 20 plot that: “Stauffenberg had bungled it, and a frontline soldier would have finished Hitler off.”

Rommel’s writings from as early as 1942 demonstrate increasing antagonism towards Hitler and the Nazi government. Forced to rely on the Führer’s leadership from the battlefield, Rommel found Hitler more than lacking as a leader, and was jarred by the fact that Hitler did not seem to care about the fate of the troops or German civilians. Rommel began socializing with anti-Nazi dissidents in 1943.

“I began to realize that Adolf Hitler simply did not want to see the situation as it was, and he reacted emotionally against what his intelligence must have told him was right,” Rommel wrote in his memoirs about interactions with Hitler in 1942.

By Rommel’s own admission, the 1944 Allied invasion of Normandy pushed him to his limits. “My nerves are pretty good, but sometimes I was near collapse. It was casualty reports, casualty reports, casualty reports, wherever you went. I have never fought with such losses,” Rommel told his son in mid-August 1944 at their home in Herrlingen. “And the worst of it is that it was all without sense or purpose…The sooner it finishes the better for all of us.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

“Can’t We Defend Ourselves?”

On the last day of his life, Rommel and his son had breakfast shortly after 7 a.m. and took a walk in their garden. Rommel announced that two generals from Berlin were arriving to meet him at noon. By that time, many of Rommel’s associates had been executed or arrested. Rommel expressed a lingering hope of being sent to the Eastern Front. Before meeting with the Nazi emissaries, Rommel changed into his Afrika Korps tunic.

Hitler’s henchmen, Wilhelm Burgdorf and Ernst Maisel, arrived at noon and politely asked to speak with Rommel alone. After isolating Rommel, they presented him with a final sadistic choice: commit suicide by cyanide, or face trial in a so-called People’s Court (Volksgericht). If Rommel refused to end his own life, they warned, his family also would be imprisoned and face the People’s Court. These show trials usually ended in grim deaths.

For example, dissidents Hans and Sophie Scholl were guillotined after facing a People’s Court in 1943. Officers implicated in the July 20 plot against Hitler had been hung on meat hooks and strangled with piano wire; their trials and executions were widely publicized to terrorize potential dissidents.

Rommel agreed to commit suicide, but insisted on being able to tell his family what was happening. The Nazis agreed—on the condition of the secret being kept in absolute silence.

Rommel realized the Nazis wished to execute him quietly to save their propaganda image of him. Therefore he expected them to keep their sinister bargain about not persecuting his family due to the regime’s interests. He explained this to Manfred after announcing in a tense voice: “In a quarter of an hour, I’ll be dead.”

The teenager, shocked and desperate, was ready to fight. “Can’t we defend ourselves?”

“There’s no point,” Rommel cut him off. “It’s better for one to die than for all of us to be killed in a shooting affray.”

Also present in the house was Capt. Hermann Aldinger, an old friend of Rommel’s from World War I. The pair, both from Württemberg, had been best friends for years since fighting alongside each other as infantrymen. Over the years, Rommel kept Aldinger on his staff.

The Nazis had tried to keep Aldinger away from Rommel by distracting him with a conversation in the hallway. Eventually Rommel summoned Aldinger and told him what would happen. Aldinger reacted with outrage and desperation. He was ready to go down in a hail of bullets rather than simply surrender his friend to die alone. However, Rommel refused.

“I must go,” Rommel insisted. “They’ve only given me 10 minutes.”

Rommel put on his overcoat and made his way out of the house accompanied by Manfred and Aldinger, pausing once to stop his pet dachshund from trying to follow him. An SS driver waited in a car outside. The two generals offered hypocritical salutes. As villagers watched, the last gestures of goodbye Rommel could give his son and his old war buddy were quick handshakes. Then Rommel was driven out of town, with Burgdorf and Maisel sitting on either side of him in the back seat to prevent him from escaping.

Surrounded by Gestapo

Rommel met his death in an isolated wooded area which is much farther from the town of Herrlingen than one might imagine. The road leaves the village, passing up a steep hill and through a dense forest. Eventually the forest diminishes into open fields, which in 1944 were hemmed with more trees. It is a quiet and lonely spot—far removed from civilization and potential witnesses. The woods were infested with Nazi gunmen.

“Gestapo men, who had appeared in force from Berlin that morning, were watching the area with instructions to shoot my father down and storm the house if he offered resistance,” Manfred later wrote.

What happened after that point remains open to question since the surviving witnesses are less than credible. Those present who later offered their version of events had all been directly involved in causing Rommel’s death.

Their testimony gives rise to doubts. For example, the SS driver claimed he stepped away from the car for 10 minutes and returned afterwards to find Rommel “sobbing” in death throes; however, this seems untrue since the type of cyanide capsule presented to Rommel is usually lethal in about three minutes. Maisel, who survived the war, claimed he was not present in the car when Rommel died, but stated Burgdorf was there instead—at the time of this allegation, Burgdorf was conveniently dead, having committed suicide in Berlin in May 1945.

Furthermore, the SS driver claimed Rommel’s service cap and Field Marshal’s baton had “fallen” from him in the car. However, postwar interviews collected by U.S. Army intelligence officer Charles Marshall and British historian Desmond Young revealed that the Nazis took these two items as trophies and later kept them on a desk at Hitler’s headquarters. Burgdorf allegedly boasted about them and showed them to visitors. Learning of this, Aldinger became determined to reclaim these belongings and managed to return them to Rommel’s family in November 1944. It is possible that, instead of merely picking up belongings that “fell” in the car, Hitler’s henchmen had pried the hat and baton from Rommel’s body.

THREATenING A DOCTOR

A statement given by Dr. Friedrich Breiderhoff to the Cologne police department in 1960 described how the Nazis forced him to “examine” Rommel after death and attempt “resuscitation” for show—even threatening the reluctant doctor with a gun. Although Breiderhoff found the empty cyanide capsule Rommel had taken, he was forced to write the death off as a “heart attack.”

The Nazis used Rommel’s funeral as a propaganda spectacle. They claimed Rommel’s death was induced by war wounds and staged a speech promoting Hitler as the eulogy. They attempted to use Rommel in death to perform a task he was was unwilling to do in life—to motivate Germans to continue fighting.

Some people today wonder what might have happened if Rommel had chosen to fight back or face a People’s Court instead of accept such an end. Some have argued he might have inspired Germans to resist by causing a shootout at his home, or by accepting a show trial, however unlikely it was for Nazis to let the truth be known. But it seems clear that the Nazis had deliberately made the decision difficult for Rommel. They chose to confront him at home and threaten his family and friends. Rommel’s last words to his son and former war comrade indicate that the safety of people he loved was the most important thing on his mind when he decided to accept Hitler’s “offer.”

When the truth behind Rommel’s death emerged after the war ended, many of his former enemies from Britain, France and America were deeply moved by what had happened to him and made trips to Herrlingen. Veterans from the British Eighth Army and the U.S. Army have left tributes at Rommel’s grave and the site where he died, which is marked by a large boulder with an inscription in his memory. MH

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.