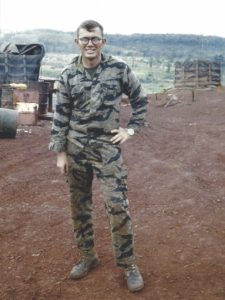

Capt. Phil Bernstein, commander of the 265th Radio Research Company, the cover name for the secretive intelligence-gathering Army Security Agency, watched as his new soldier arrived at the company’s Camp Eagle headquarters in northern South Vietnam in late December 1970. As a military truck rolled in from the helicopter landing zone carrying Staff Sgt. Ed Keith, Bernstein noticed that the new intel analyst was wearing nonregulation camouflage fatigues bearing a Special Forces patch and lugging two heavy Army footlockers.

Bernstein remembers Keith as having “hand grenades, belts of ammunition, knives, Claymore mines,” and an assortment of automatic weapons and pistols. That was hardly equipment needed to analyze intelligence gleaned from enemy radios and telephones.

Impressed by Keith’s background, Bernstein pulled him off to one side. “I told him I had a very weak lieutenant leading one of my platoons” and needed his experience “to prop up” the lieutenant, Bernstein said. He appointed Keith platoon sergeant and sent him off to find that unit. Bernstein, who rarely left his headquarters, never saw Keith again.

Keith had been trained in signals intelligence—listening in on radio and telephone communications to decipher the enemy’s plans and troop movements. He tested extremely high on military aptitude exams, spoke Mandarin Chinese and had quit the Army twice before enlisting a third time to get to Vietnam. Keith had worked with the Special Forces at Fort Bragg in North Carolina and was coming from the 5th Special Forces Group at Pleiku in the Central Highlands, although he wasn’t yet a qualified Green Beret when he got to Vietnam. He rarely told anyone who he worked for.

Keith had arrived in Vietnam on July 20, 1969, and was sent to the Duc Lap Special Forces Camp near the Cambodian border. When troops there found a wire strung across the ground, he quickly determined it was a North Vietnamese telephone line and installed a tap to listen in. He was also dispatched to a border region in the Mekong Delta and looked for phone lines to tap there. One day when he was with a small contingent of local fighters recruited by Special Forces, two enemy machine guns opened fire. Keith grabbed his radio operator, jumped into a bomb crater half filled with water and hid submerged as two Air Force F-100 Super Sabre fighter-bombers saturated the area with deadly napalm. Once the shooting stopped, the pair surfaced.

When Keith’s group returned to the U.S. in November and December 1970, he still had several months before he was scheduled to leave Vietnam. The Army ordered him north to the 101st Airborne Division at Camp Eagle for reassignment. While waiting, Keith completed a correspondence course to qualify as a full-fledged special operations paratrooper, entitling him to wear a green beret with the Special Forces insignia.

An acquaintance stationed at Camp Eagle, Sgt. 1st Class Douglas Bonnot, was the noncommissioned officer in charge of Bernstein’s 265th Radio Research Company, attached to the 101st Airborne Division. He heard Keith was 5 miles away at Phu Bai and set out to recruit him.

A career intelligence specialist, Bonnot bristled at what he perceived to be his parent organization’s view of its mission. The Army Security Agency was set up after World War II to collect and distribute intelligence for strategic planning in preparation for future wars. In Bonnot’s view, it was too passive when it actually went to war.

Bonnot was often frustrated when intelligence analysts picked up information about the North Vietnamese Army’s intentions, but the information was filtered through several layers of command before it arrived in the field—too late to be of any use. Bonnot’s immediate boss, 1st Lt. Bruce Rollman, called that “the perishability of intelligence.” In an interview long afterward, Rollman said, “If you can’t get it to the guys in the field exactly when they need it, you might as well forget about it.”

Bonnot believed his intelligence analysts should not be restricted to immobile defensive enclosures surrounded by high chain-link fences and topped by concertina wire deep inside Army bases. He wanted them closer to enemy radios and telephone wires. However, company commander Bernstein maintained that the Army’s electronic eavesdroppers, with their super-high security clearances, should never be placed so close to the enemy that they were at risk of capture. But that’s where Keith wanted to be.

“I was always looking for a fight,” Keith said. “I thought I was going to die in Vietnam, and I wanted to do the best I could before that happened.” He quickly teamed up with Bonnot, who oversaw more than 200 Radio Research troops scattered around firebases and outposts in South Vietnam’s northernmost region.

In December 1970, Bonnot’s radio monitors picked up clues that the North Vietnamese were moving large numbers of troops into positions just inside the Laotian border and around the town of Tchepone at the top of the Ho Chi Minh trail, used to funnel supplies to communist forces in South Vietnam. The analysts thought the maneuvers were preparations for a spring offensive against U.S. forces below the Demilitarized Zone separating North and South Vietnam. The Radio Research team didn’t realize the North Vietnamese had achieved an intelligence coup of their own. They had learned about a U.S.-South Vietnamese plan for an invasion of Laos to cut the trail network and were setting a trap.

The top-secret plan instigated by U.S. strategists constituted a last desperate attempt to hamstring the NVA before it could reach the South. Some senior military officers—including Gen. Creighton Abrams, top U.S. commander in Vietnam—suggested the proposed invasion might end the war. American officials in Saigon believed a successful offensive would weaken the enemy forces and lead to lower U.S. casualties. President Richard Nixon, already focused on his 1972 reelection campaign, hoped reduced losses would soften anti-war sentiment. To support the planned invasion of Laos, the U.S. Army reopened the abandoned Marine base at Khe Sanh, near the Laotian border and just south of the DMZ.

Informed of the invasion plan only days before execution, the Radio Research boys scrambled to scrounge, repair and deliver radios and other intelligence-gathering gear to forward firebases. In Bonnot’s account of the operation in his 2010 book The Sentinel and the Shooter, he said that when parts weren’t available his team cut equipment out of other units’ military vehicles, sometimes using bolt cutters, to obtain radios, batteries and other needed items.

Keith was ordered to set up a secure communications link at Khe Sanh, the operation’s forward headquarters. He persuaded an Army engineer with a bulldozer to dig a deep cross-shaped trench to hold a radio teletype machine and related gear for gathering, analyzing and distributing coded messages. The bulky setup was used to link Bonnot’s Khe Sanh intelligence operatives to their headquarters, to the 101st Airborne’s intelligence staff at Camp Eagle, and even to analysts as far away as the National Security Agency at Fort Meade, Maryland.

The invasion, designated Lam Son 719, began on Feb. 7, 1971. A few days later, Keith took a helicopter to the division headquarters at Camp Eagle about 50 miles to the south. It was his turn for a shower, a hot meal and a comfortable night’s rest. The 29-year-old sergeant was asleep at about 3 a.m. when a private woke him with an order to immediately carry a classified message to Brig. Gen. Olin E. Smith, assistant commander of the 101st Airborne, at Khe Sanh.

The officer on duty ordered a UH-1 “Huey” helicopter and mustered a crew to fly Keith and his top-secret message to Smith who, it turned out, was not at Khe Sanh, but rather spending the night at Quang Tri, a base somewhat closer to Camp Eagle. After Keith landed at the camp, he was directed to a clutch of mobile-home trailers that served as generals’ quarters. He knocked on a door and roused a sleeping general—unfortunately the wrong one, a lieutenant general, who redirected the sergeant to the correct trailer.

Keith woke up Smith and handed him the 24-page intelligence report. The general asked if he had read it. Keith acknowledged that he had. The intelligence had come from a North Vietnamese radio transmission intercepted and translated by the Radio Research team. The document, declassified years later, disclosed that the North Vietnamese knew that American ground forces were ordered not to cross the Laotian border and would be limited to support functions for the South Vietnamese troops conducting the invasion. The NVA intended to mass its own forces inside Laos, wait for the South Vietnamese infantry and armor to drive deep into the country, then cut them off and chew them up before they could get back to South Vietnam. That is, in fact, what would happen in the coming weeks.

Smith read the report and discussed it with Keith before a scheduled meeting that morning with Abrams, who was flying from Saigon to discuss the latest intelligence. Keith lay down on the grass outside the briefing room for some sleep.

When the generals’ meeting ended, Smith flew Keith back to Khe Sanh, just a few minutes away by helicopter. There he introduced Keith to Lt. Col. Robert Molinelli, the commander of the 2nd Squadron, 17th Cavalry Regiment, a unit of the 101st Airborne Division.

Keith told Molinelli he wanted to fly over the terrain in Laos and help locate the enemy. The sergeant believed his partial color blindness enabled him to spot targets others couldn’t see. Molinelli referred him to Maj. Jim Newman, commander of the 2nd Squadron’s C Troop “Condors.” Newman was quickly becoming a legend in the air cavalry for his daring exploits, particularly in rescuing downed helicopter crews under enemy fire.

Despite standing orders barring signals intelligence specialists from participating in risky missions, Keith wanted to use his skills to help Newman’s Condors fight in Laos rather than operate his radio teletype machine at Khe Sanh. With Bonnot’s blessing—but without telling commanding officer Bernstein—Keith jumped aboard every flight he possibly could.

At that point, Keith and Bonnot were operating in what they jokingly called the “605th Mobile Guerrilla Force (Provisional),” a made-up unit with a fictitious shoulder patch they designed featuring a white tiger on a red and black background. They had the unauthorized patch expertly embroidered by one of the ubiquitous Vietnamese civilian shops outside American bases. The “605th” had only a handful of members, all close buddies Bonnot trusted, who shared the radio unit’s intelligence directly with troops heading into combat.

Bernstein had no idea that some of his men were operating out front. “I had guys scattered all over the place at that time,” he said. “I didn’t really know who was where.”

The first time Keith flew with Newman, a couple of weeks after the invasion’s Feb. 7 kickoff, they had crossed into Laos when the major received a radio message that a South Vietnamese ranger base was under attack and in danger of being overrun. Newman turned toward the base, a few miles to the north. The crew could see artillery shells exploding all over the outpost. Keith spotted at least some of the enemy artillery. Newman called in AH-1 Cobra helicopters and Air Force jet fighters that silenced the guns.

A few minutes later, Newman turned toward Keith behind him and said over the intercom:

“How’d you like to fly with us?”

“All day every day, sir.”

“Fine. You’re flying with us now.”

Back at Khe Sanh, Newman told Keith he wanted his help searching for an underwater bridge the North Vietnamese were using, likely as a link to their supply depot close to Tchepone.

Although the bridge was invisible from the air in daytime, at night the NVA drove convoys across it. Newman’s helicopter approached at about 5,000 feet. Keith suggested they drop down to treetop level, turn sharply to the right and fly east across the river to give him a good look. During the descent, a North Vietnamese tank that Keith spotted fired at them. Just moments later Keith saw and plotted the location of the submerged bridge. Newman called in waiting Air Force bombers that took out both the bridge and the tank.

Keith recalled that during subsequent flights with Newman on March 7, 8 and 15, 1971, their chopper was hit by enemy fire intense enough for Newman to land in Laos and check the damage before returning to Khe Sanh.

On March 17, Capt. Dennis Urick, flying reconnaissance in Newman’s place, told Keith to come with him. When Keith climbed aboard the Huey, borrowed from another unit, he discovered there was no cable to connect him to the aircraft intercom and radios. He was about to get off when Urick told him to take the door gunner’s cable.

Keith sat on the right side of a long bench running across the rear of the cargo compartment. He carried a couple of survival-type sheath knives and wore around his neck a camouflage bandanna fashioned from a bandage in a first-aid kit. Keith also carried sophisticated gyro-stabilized binoculars that helped sharpen distant images, Urick recalled.

The Lam Son 719 invasion was in desperate straits. South Vietnamese ground forces in Laos were taking a beating. The NVA, as planned, let the invasion force land with little resistance, but five weeks later the South Vietnamese were strung out and bleeding, trying to fight their way home.

Among the worst hit was the 4th Battalion, 1st Regiment of the 1st Infantry Division, one of Saigon’s elite units, which demonstrated its courage repeatedly on the battlefield. Its firebase was surrounded and being hammered by NVA artillery. All the 4th Battalion’s officers had been killed. The ragged band of survivors was desperate for ammunition—or a ride out.

Heavy fire took down several American helicopters attempting to reach the beleaguered unit. Urick’s crew tried to pinpoint the enemy gun positions so AH-1 Cobra helicopter gunships could silence them long enough for other Hueys to rescue downed American crewmen and the remnants of the South Vietnamese battalion. Keith spotted some likely targets and asked Urick to go around again to help him get a fix on those guns.

The crew chief, Spec. 5 Richard Frazee, saw the escarpment below light up as enemy gunners on the ground fired colored tracer rounds that whizzed past the circling helicopter. On the pilot’s third and lowest pass, six rounds from a .51-caliber machine gun ripped through the chopper’s belly. A white-hot incendiary bullet tore upward through the sole of Keith’s left boot, came out through the top of his knee, hit his wrist and shoulder, and cut his mic cord before smashing into the helicopter’s transmission assembly controlling the main rotor overhead.

Frazee, firing his M60 machine gun from the left rear door, heard someone shouting over the intercom: “Who’s hit? Who’s hit?” He looked down and saw his own flight suit and chest armor soaked in blood. Frazee thought he was wounded but then turned and noticed Keith on his back in the cargo bay.

Most of Keith’s leg was missing. A few white ligaments were twitching, still attached to Keith’s foot inside his boot.

Keith saw part of his leg lying in the co-pilot’s lap and red warning lights flashing on the dashboard. Frazee couldn’t reach Keith because the webbing of the bench seat blocked his way. He unhooked his safety strap and climbed out on the helicopter’s skid to get around the seat, but every surface he touched was slick with melted fat and blood from Keith’s wound. Frazee lost his grip and thought he would fall from the aircraft but managed to grab onto a strut and pull himself into the cargo compartment where Keith lay on the floor.

A tourniquet was tightened around Keith’s thigh to stanch the bleeding. Keith and Frazee differed later on the details. Frazee recalled reaching for a tail rotor tie-down strap that he wound around the stump. As Keith remembered it, he used his bandanna to cinch up what remained of his leg, using his knives to twist the bandage tight.

Urick saw Keith give him a thumbs-up sign when the tourniquet was in place, then turned back to steady the violently vibrating chopper. The pilot radioed his gunship escorts to cover him as he hastily descended, calculating that if he lost power he was better off autorotating—essentially gliding—close to the ground in search of a place to land.

The Huey made it back to Khe Sanh, where Urick executed a “controlled crash” on the landing pad outside the aid station. When medics saw the extent of Keith’s wounds, a medevac helicopter was summoned to fly Keith to the Army’s 18th Surgical Hospital at Quang Tri, where his leg was amputated above the knee that night.

Hours later, Urick and his crew flew to Quang Tri to visit Keith in the hospital and gave him a black Stetson “cav hat,” the unauthorized but proud symbol of cavalry troops, and a .51-caliber bullet they dug out of the shot-up Huey.

Keith was transferred to military hospitals in South Vietnam and Japan before being flown to Letterman Army Medical Center in San Francisco. He underwent major surgery to clean up the leg wound, hastily treated during the emergency amputation, and then had more surgery to remove shrapnel from his arm and shoulder. Two-and-a-half months after Keith had been wounded, he was sent home to his family in Corcoran, California.

At Letterman, Keith had begun to feel “phantom limb” pain, a condition doctors believe is rooted in the brain or spinal cord. Keith described it as a burning sensation in his missing leg so intense he couldn’t concentrate to read a book or watch television. He tried college but didn’t finish. He was married for a time but divorced. He was unable to hold a job for long.

“I’d started taking drugs within three months of getting out of the Army,” Keith said. “I tried anything I could get—not illegal drugs, but anything they had that might stop the pain.” He became addicted and his health deteriorated.

In 2015, a doctor suggested Keith try a generic drug, venlafaxine, sometimes used to treat depression and not recognized as a painkiller. Within 48 hours, the phantom limb pain was practically gone. “I still have pain in the leg but nothing like I used to have,” Keith said a couple of years later.

Bonnot and Urick campaigned to get Keith a Silver Star in recognition of the many American lives they say he saved through the use of his intelligence expertise on combat missions. Those efforts infuriated Bernstein, the 265th Radio Research Company’s former commander. Bernstein, who later worked as a civilian in military intelligence and retired as a colonel in the Reserves, complained that Keith had decided to “go rogue and play Rambo” in Vietnam.

Keith, who had a special top secret clearance, had gone into the field and exposed himself to possible capture. “He wasn’t supposed to be doing that work,” an outraged Bernstein said. “That wasn’t his mission.”

Six months after Keith was wounded, Bernstein, on his way home from Vietnam, had called Keith and told him that he felt terrible about what had happened, but added that if he had known Keith was on that mission he would have relieved him of his duties.

Bernstein said he didn’t learn until four decades later the full details about the efforts of Keith, Bonnot and Rollman (who as a lieutenant supported the actions of the two sergeants) to provide secret intelligence directly to troops in the field. Bonnot wrote about their activities in an alumni newsletter. Had he known about them in Vietnam, Bernstein said, “I would have relieved all three soldiers and sent them to higher headquarters in Da Nang for insubordination.”

Bernstein drafted a letter to the Army’s personnel chief opposing the Silver Star award but after seeing a photo of his one-time subordinate as an old man, he destroyed the unsent letter. “Let the old man go to his grave with an award,” Bernstein said. “Who am I to stop him from getting his last honors?”

Ed Keith died on Oct. 4, 2018, at 76, of multiple organ failure. He never got the Silver Star. V

Michael Putzel is a former reporter and bureau chief for The Associated Press and The Boston Globe and the author of the Vietnam War book The Price They Paid: Enduring Wounds of War. He lives in Washington, D.C.

This article appeared in the December 2020 issue of Vietnam magazine. For more stories from Vietnam magazine, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: