Moves to establish friendly relations between the U.S. and postwar Vietnam were marked by 20 years of diplomatic twists and turns.

On April 30, 1975, North Vietnamese tanks burst through the gates of Saigon’s Presidential Palace, bringing an end to the Republic of Vietnam. Halfway around the world, ralliers in New York’s Central Park celebrated the fall of South Vietnam as a victory for national liberation and the defeat of American imperialism. They waved placards embossed with “VIETNAM IS FREE,” and self-congratulations were the order of the day. Hardcore radicals and the Old Left protest movement were present—including Dr. Benjamin Spock and priests/brothers Daniel and Philip Berrigan. Yet this gathering was different from the anti-war protests of the 1960s and early 1970s. There was a paucity of students, academics and, most important, moderate politicians who supported legislation limiting U.S. assistance to South Vietnam.

North Vietnam’s Politburo members, always keen observers of activities in the United States, viewed the rally in New York and a similar one in Berkeley, California, as an indicator that Vietnam remained center stage in American consciousness and would figure prominently in U.S. foreign policy. They believed anti-war groups remained an important political force that would pressure Congress to authorize a large aid package for their war-torn country.

However, the aging revolutionaries in Hanoi grossly misread the mood of the American public, the attitude in Congress and the diminishing ranks of their supporters in the United States. These miscalculations, combined with changing national interests in America, would delay for nearly 20 years the official “normalization of relations”—a process that allows embassies to be established, businesses to engage in trade and citizens to travel between the two nations.

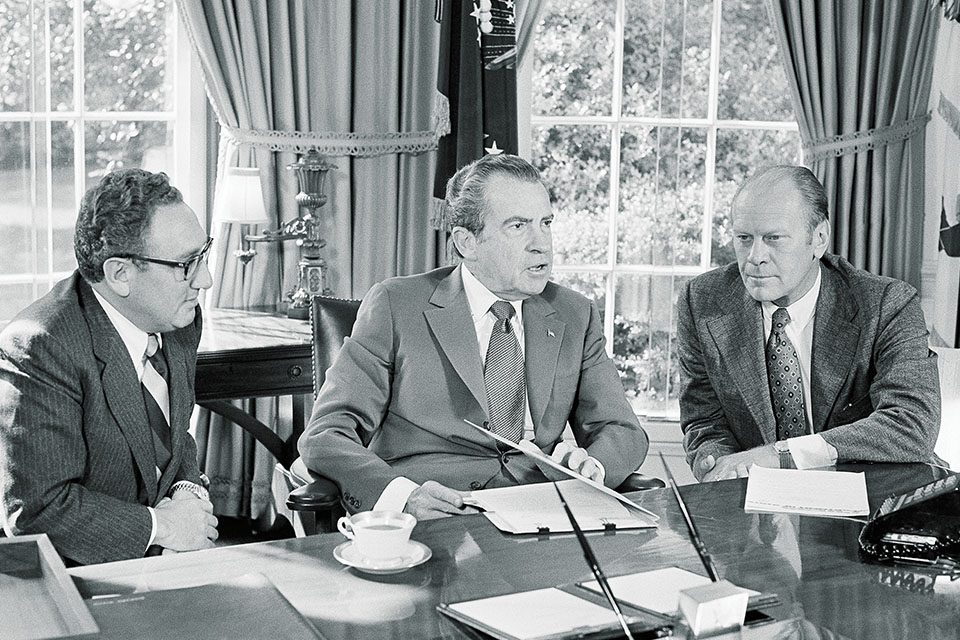

“The U.S. government will contribute to the postwar reconstruction in North Vietnam without any political considerations whatsoever,” President Richard Nixon wrote in a secret letter to Prime Minister Pham Van Dong in February 1973. “U.S. preliminary studies show that programs appropriate for a U.S. contribution to the aforementioned postwar reconstruction will amount to about $3.25 billion in nonrefundable aid.” But there was a caveat: Any reconstruction aid would require congressional approval. Implicit in the offer was Hanoi’s adherence to the Paris Peace Accords, signed on Jan. 25, 1973, which provided for the withdrawal of U.S. troops and reunification of North and South Vietnam through a peaceful solution.

The North Vietnamese, however, contended that Nixon’s aid offer did not require them to abide by the peace agreement. They took it as a solid commitment and integrated the $3.25 billion in their postwar plans—even as they initiated the military offensive that would blatantly violate the accords and topple South Vietnam.

Flush with the euphoria of their April 1975 victory, Vietnam’s Communists were not prepared for a belligerent response from the United States. Gerald Ford, who became president after Nixon’s resignation on Aug. 9, 1974, immediately imposed a trade embargo, set aside any possibility of assistance, froze Vietnamese assets in the United States and confirmed that America would veto Vietnam’s request to join the United Nations. The U.S. also restricted travel to Vietnam, cut telephone and postal connections and banned transmissions of money from America to Vietnam. The U.S. government further flexed its economic muscle by blocking loans from the World Bank, Asian Development Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Japan and other allies were pressured to follow America’s lead; most complied.

Without access to Western capital, Vietnam turned to its wartime benefactors, the Soviet Union and China. Neither was willing to bolster the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, the country’s post-unification name, with a Marxist version of the Marshall Plan, which used American money to rebuild Europe after World War II. Instead, the Soviet Union offered loans, usually with stringent repayment provisions, and European governments under Soviet control, led by East Germany, were similarly tight-fisted. But the biggest disappointment was China. Once a dependable ally, its contribution was perceived as a pittance.

The unified Vietnam was operating in unfamiliar territory. During the war, North Vietnam was not required to manage its economy. Nearly everything—weapons, clothing, medicine and food—came from outside sources, and Vietnamese authorities served merely as distributors of goods. There were few experienced economists, and those in the government rigidly adhered to the Soviet model: tight state controls, centralized decision-making and rapid industrialization.

The relatively small cash influx was spent exclusively in the North on sophisticated enterprises rather than on improved housing and basic infrastructure. Steel plants, a high-tech paper mill and a modern hospital were among the ill-chosen reconstruction projects that languished because the managers and operators were unable to maintain them. The economy began to flounder.

Cadres from the old North Vietnam took over all governance of the defeated south. Hanoi’s Communist guerrilla allies in the South, the Viet Cong, were either treated like second-class revolutionaries or completely shoved aside. The Politburo also opted for punitive measures to “reform” the South, sending former military and government personnel to re-education camps, collectivizing agriculture and shuttling city dwellers to inhospitable regions called “new economic zones,” where they worked on previously uncultivated or unproductive land. When they could, people returned to their former homes or tried to leave the country. The international trade embargo added to the litany of woes. American-built manufacturing plants shut down because they lacked spare parts. Visions of a socialist utopia were not coming to fruition.

Hanoi watched the 1976 presidential election with great anticipation. The Democratic candidate, former Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter, campaigned on a promise to bind the wounds of war and obtain a full accounting of American servicemen missing in action. He was particularly critical of Ford’s intractability in dealings with Vietnam’s leaders, citing it as the reason there was no movement on the MIA issue. Carter’s victory in November was not a sweeping mandate, 50.1 percent of the popular vote, but it was music to the ears of the Vietnamese government.

Not long after his inauguration in January 1977, Carter established a five-man commission headed by Leonard Woodcock, president of United Auto Workers and a critic of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, to begin the rapprochement. Alongside Woodcock were three vocal opponents of the war and U.S. Rep. G.V. “Sonny” Montgomery, a conservative Mississippi Democrat who chaired the House select committee on Americans missing in action. The group traveled to Hanoi in March 1977.

The delegation had hardly settled in the capital city when the foreign minister, Nguyen Duy Trinh, called an unscheduled meeting and announced that the United States was under a legal and moral obligation to provide $3.25 billion in reconstruction aid. In their view, the U.S. was refusing to recognize Vietnam as the victor in a long, costly war and reneging on a commitment to pay reparations. This attitude set the tone for three days of talks.

Woodcock repeatedly stressed that no American, regardless of the person’s political views, would agree to pay reparations as economic aid or to “buy back” the remains of missing servicemen. Vietnamese negotiators disregarded Woodcock’s explanation that “reparations” carried a pejorative ring in the United States. As a result, little was accomplished. Upon conclusion of the meetings, the Vietnamese government handed over what was thought to be the remains of 12 Americans. One was later determined to be a Vietnamese male.

Prime Minister Dong, in a letter given to Woodcock for Carter, dangled the possibility of an accommodation in the near future. He proposed a May 1977 meeting in Paris, and Carter immediately accepted. The quick response convinced Dong and his associates that the new administration was malleable and would ultimately agree to aid. They saw it as an indicator that Vietnam was still at the epicenter of U.S. concerns and Ford’s tough approach was a thing of the past.

In the meantime, Nhan Dan, the official party newspaper, broke the story of the heretofore secret Nixon letter, hoping to create a sense of guilt in the United States and energize public opinion to support compensation. The revelation, however, had little impact on America’s now-dormant anti-war movement and even less on the majority of its citizens, who wanted to put the Vietnam experience behind them. Since the war and draft ended in January 1973, college campuses had quieted down and student interest in Vietnamese affairs had faded. Celebrities like Jane Fonda and Muhammad Ali, whose outrage had grabbed attention when U.S. servicemen were coming home in caskets, had gone silent. The support Hanoi had come to count on was no longer a potent force.

Carter’s envoy at the Paris talks was 36-year-old Richard Holbrooke, assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs, a wunderkind in Democratic policy circles who had begun his State Department career as a foreign service officer in Vietnam from 1963 to 1966. His boss, Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, was convinced an agreement would ensure stability in Southeast Asia. Like the president, Vance believed that discord caused by the war would continue to fester as long as Vietnam was ostracized. Thus, Holbrooke was committed to reaching an agreement in Paris.

The Vietnamese delegation was led by Phan Hien, the deputy foreign minister, whose marching orders were to secure the $3.25 billion reconstruction package. Holbrooke offered to support Vietnam’s admission to the United Nations, lift the trade embargo and normalize relations, but Hien countered that nothing was possible without U.S. dollars. He then abruptly left the meeting to hold a press conference, where he read aloud Nixon’s 1973 letter. Hien announced that aid was a requirement for any future discussions; it was a serious mistake. Americans wanted an accounting of those still missing, but no one would condone giving their former enemy billions of dollars to start the process.

Reaction on Capitol Hill was immediate. Two pieces of legislation were passed with overwhelming support. The first prohibited the Carter administration from “negotiating reparations, aid or any other form of payment to Vietnam.” The second renounced Nixon’s offer of reconstruction aid.

The Vietnamese Communists were not facing the same Congress that authorized the 1973 Chase-Church Amendment, prohibiting U.S. military action, including air support, and any other assistance to shore up South Vietnam’s defenses. In 1977, congressional denial of the Vietnamese Communists’ demands did not generate any meaningful backlash. Public statements of anti-war groups were lucky to make the back pages of national newspapers.

Holbrooke made a fresh offer: The two countries would establish liaison missions in Washington and Hanoi, a move that could lead to full recognition. The Vietnamese rejected it out of hand. Hien proposed that a secret aid agreement be signed without congressional knowledge. He was apprised that such deals were impossible, and discussions ended soon thereafter.

Carter’s 1977 Vietnam diplomatic offensive ended in abject failure. His administration changed course and looked for ways to improve ties with China, whose strong support for Vietnam during the war was no longer an obstacle to better relations with the United States. Additionally, China was increasingly at odds with its former ally over matters such as Vietnam’s hostility toward the Chinese-backed regime in Cambodia and the persecution of ethnic Chinese, particularly merchants in Cholon, the commercial hub of Saigon, which had been renamed Ho Chi Minh City in 1976.

Being put on hold by the United States was a new, uncomfortable paradigm for the aging warriors in Hanoi. They had been successful by waiting out their enemies, but their traditional patience was not a viable strategy in the postwar world. Vietnam’s economy was sinking rapidly from mismanagement, draconian reformation policies, meager assistance from Communist allies and the cost of maintaining the largest army in Southeast Asia.

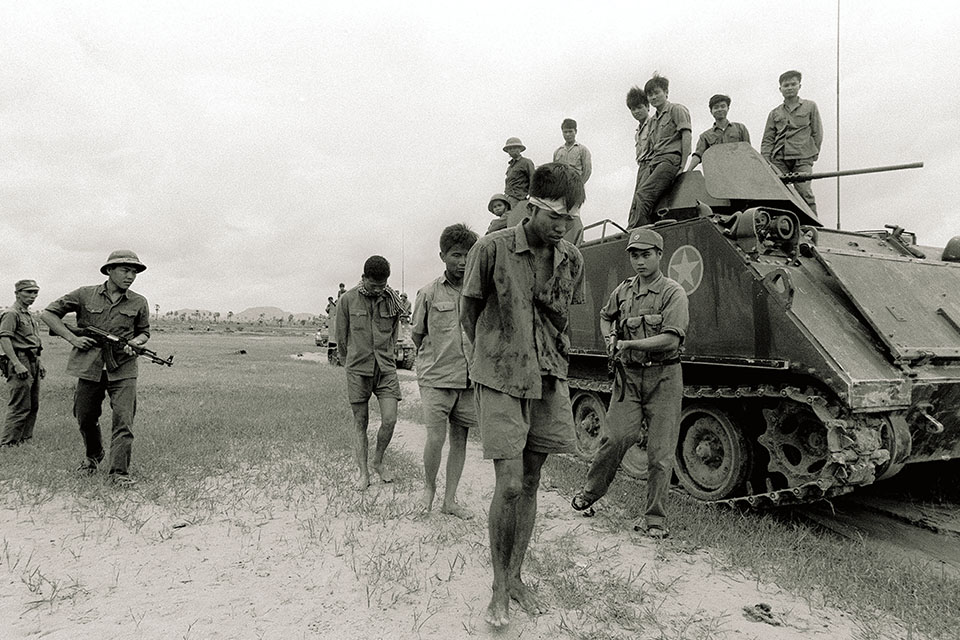

Vietnamese troops were regularly engaged in battles along the Cambodian border as they fought with their onetime Communist comrades, the Khmer Rouge, which had overthrown Cambodia’s pro-West government on April 17, 1975—even before the North Vietnamese Army captured Saigon. Once Vietnam was unified, Cambodia experienced a resurgence of the old tensions between native Cambodians and ethnic Vietnamese living there. The Khmer Rouge, led by the despot Pol Pot, claimed that Vietnam was occupying enclaves that had belonged to Cambodia before the French colonial era. Raids and counterattacks into these disputed territories on the border became commonplace.

Meanwhile, stories of Communist brutality in Vietnam’s punitive re-education camps were filtering out of the country. That information and the plight of masses of refugees still fleeing the country, years after the war ended, were front-page news. The world saw images of “boat people,” crowded into unsafe vessels, trying to escape oppression and hardship. More often, those who survived storms and pirates were destined for squalid refugee camps. No more was Vietnam seen as David battling the American Goliath. The Vietnamese who were once lauded as freedom fighters were now portrayed in the Western press as bullies who beat up on their own citizens and threatened neighbors.

Wounded pride and bruised egos aside, Vietnam’s leadership did realize that some normalization with the United States was more important than ever. Better relations with the U.S. would offset increasing strains with China, whose aid to Pol Pot added to Vietnam’s problems.

But Washington seemed to be pushing Vietnam to the periphery of its interests while shifting its attention to China. Furthering that perception was Carter’s national security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, who put full diplomatic recognition of China on the fast track. During 1977, Hanoi’s Politburo had clearly overplayed its hand.

Desperate to restart talks with the U.S., the Vietnamese sent a message to the Carter administration in July 1978, stating a willingness to negotiate without any preconditions. But this time, the administration was in no hurry to respond. Any accord with the Vietnamese would hinder America’s improved relations with China, and Hanoi’s bargaining position was further eroded by intelligence indicating that Vietnam was massing its military forces along the Cambodian border. The U.S. government informed the Vietnamese Foreign Ministry that there could be a private session during the September 1978 meeting of the United Nations General Assembly in New York, a venue that ensured a low-key affair.

Again Holbrooke was thrown into the breach. Across the table was Nguyen Co Thach, a rising diplomat who would become foreign minister in 1980. Thach opened the session by asking how much aid the United States was prepared to offer. A dumfounded Holbrooke reminded his counterpart they were meeting because that particular issue had been tabled. As the U.S. envoy packed his briefcase and prepared to leave, Thach did an about-face, saying that both parties could sign an immediate agreement without any reference to monetary assistance. Holbrooke said he did not have the authority to sign a normalization document but would take the request to the State Department.

Thach stayed in New York awaiting an answer; none was forthcoming. Stonewalling the United States was a favorite North Vietnamese tactic during the war. In a turnabout, Vietnam was now getting that treatment. After a month of waiting, Thach returned to Hanoi.

Not long afterward, Vietnamese Communist Party Secretary Le Duan journeyed to Moscow and signed a 25-year friendship treaty with the Soviet Union. This de facto military alliance cast Vietnam’s lot squarely with the Soviet Union. It also gave the Vietnamese a green light to deal with the Khmer Rouge. On Dec. 25, 1978, Vietnam invaded Cambodia, overthrew the Pol Pot regime, and occupied a large section of the country. The overt aggression solidified Vietnam’s status as an international pariah.

On Feb. 17, 1979, China, intent on “teaching a lesson,” crossed Vietnam’s mountainous northern border with eight army divisions—100,000 regular troops supported by 150,000 militia soldiers. The Chinese force made significant territorial gains, capturing several provincial capitals. Vietnam’s sole ally, the Soviet Union, protested but took no military action. Both sides suffered thousands of casualties. After a month of fighting, the last Chinese troops withdrew from Vietnam on March 15, leaving significant destruction in their wake.

Despite a tacit cease-fire, extraordinary tensions remained between the two nations. China posed an ever-present threat, and a Khmer Rouge insurgency against the Vietnamese-installed government kept Vietnam on a war footing, further straining the country’s moribund economy.

The post-invasion period became known in Vietnam as the Dark Years. Repression and poverty increased; some areas experienced famine. A “brain drain” occurred as people continued to flee Vietnam and more urban families were forcibly resettled in outlying economic zones. “Re-educated” former government officials, many of them capable administrators, were denied meaningful employment. Foreign aid decreased because the Soviet Union was having its own economic headaches. Some Russian advisers were recalled, creating technical voids and leaving major projects unfinished. As the 1980s began, Vietnam was close to being a failed state.

The country was saved by the departure of much of the old guard in Hanoi. Younger men with new ideas and fresh perspectives gained power as the dour hardliners passed from the scene, most significantly, the iron-fisted Le Duan, who died on July 10, 1986. Much of the new generation realized the Soviet Union had serious internal problems and was not a dependable partner. Vietnam implemented market economy initiatives and withdrew its army from Cambodia by September 1989. In the late 1980s, new officials reached out to the United States, offering full cooperation in efforts to account for American MIAs—with no strings attached.

With that change in attitude, American efforts to lift the trade embargo and restore normal relations got strong support from Vietnam War veterans in the Senate: Republican John McCain of Arizona and Democrats John Kerry of Massachusetts, Chuck Robb of Virginia and Medal of Honor recipient Bob Kerrey of Nebraska. Their service helped dampen some of the anti-Vietnamese sentiment in the United States.

McCain’s voice resonated with the American public because he had endured brutal torture during five-plus years of incarceration. McCain had once told Robert Muller, a Marine lieutenant paralyzed from the chest down and founder of Vietnam Veterans of America, who had recently visited Vietnam, “Goddamn it, Bobby, what are you going back and talking to the enemy for?”

But over time, McCain’s attitude softened, although he still referred to his torturers as “gooks.” As he exorcised his wartime demons, McCain became the leading advocate for reaching out to the Vietnamese. His stance, and those of his Senate colleagues, provided political cover for Democratic President Bill Clinton, another proponent of improved relations, who was sworn into office in January 1993.

On July 11, 1995, Clinton removed all sanctions against the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and established full diplomatic ties. The person he chose as the first U.S. ambassador to Vietnam was former prisoner of war and retired Air Force Col. Pete Peterson, a Florida Democrat in the House of Representatives. Ironically, two decades after the fall of Saigon, the road to reconciliation was paved by men who fought in the war and opened by a man who manipulated draft deferments to avoid it.

John Howard was in the U.S. Army for 28 years, retiring as a brigadier general. He served two tours in Vietnam as a combat infantryman.