At this moment Lee’s best information came from what he could see with his own eyes. From just behind the Confederate lines spread north to south along Knoxlyn Ridge, he observed a parallel Federal deployment across Herr’s Ridge. Based on the flags displayed and prisoners taken, he was facing one Union corps. At this point approaching midday, he preferred to let combat end. Although Heth’s Division had been roughly handled in the morning fight, the rest of Hill’s Corps was close at hand and not under any immediate threat. The first of Longstreet’s men were transiting the Cashtown Pass and Lee expected that the remaining two divisions from Ewell’s Corps were completing their march via roads north of Gettysburg. There was ample reason to use the rest of July 1 to consolidate his army.

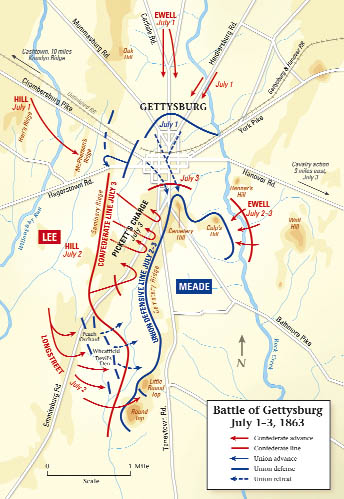

Ewell, however, had altered course when his maps indicated that he could save time by routing his columns through Gettysburg rather than around it. This brought his leading elements into contact with the Union infantry that had bested Heth shortly after midday. Despite specific orders to avoid any major engagements until the army was concentrated, Ewell (who afterward claimed that he believed Hill’s Corps urgently needed the help) pitched into the fight, extending the combat to Gettysburg’s north side where a second enemy corps—the XI Corps—was encountered.

Ewell, however, had altered course when his maps indicated that he could save time by routing his columns through Gettysburg rather than around it. This brought his leading elements into contact with the Union infantry that had bested Heth shortly after midday. Despite specific orders to avoid any major engagements until the army was concentrated, Ewell (who afterward claimed that he believed Hill’s Corps urgently needed the help) pitched into the fight, extending the combat to Gettysburg’s north side where a second enemy corps—the XI Corps—was encountered.

Lee watched as the Federals reoriented themselves to counter Ewell’s advance. Unwilling to stand idly by while one of his corps was engaged, he reluctantly allowed Hill to press the attack. The result was some hard fighting on both the western and northern fronts that eventually compelled the Yankees to retreat through Gettysburg, closely pursued by jubilant Rebels.

Lee rode forward to Seminary Ridge, the ridge closest to the town. There he could observe that the defeated enemy soldiers were regrouping on the high ground of Cemetery Hill just to the south of the town. This would not do, but how to prevent it? Two of Hill’s divisions had taken heavy losses driving the enemy, and Lee did not believe them capable of a further effort this day. Longstreet’s column was too distant, leaving Ewell’s soldiers as the best option.

A series of messages now passed between Lee and Ewell, who led what had been Stonewall Jackson’s old command. Lee appears to have made no adjustment to having a different personality in charge. His trust in Jackson had been implicit. As he said of his late lieutenant: “I have but to show him my design, and I know that if it can be done it will be done.”

Now Lee was giving Ewell the same degree of latitude by suggesting or urging an action, not demanding it, though Ewell, for his part, apparently preferred more specific orders.

Ewell indicated to Lee a willingness to resume the attack, but only if he could get Hill to cover his right flank. Despite having the one unengaged division of Hill’s Corps close at hand, Lee insisted that Ewell would have to act alone. (When questioned on his decision to withhold these 7,000 fresh troops, Lee answered “that he was in ignorance as to the force of the enemy in front,…and that a reserve in case of disaster, was necessary.”) Worried about a possible enemy threat to his own left flank, and with no help offered for his right, Ewell decided to stand pat. In time Lee would fault Ewell for not doing more. Conversing after the war with Cassius Lee, a trusted cousin, he expressed his regret over Ewell’s hesitancy. “[Stonewall] Jackson,” he said, “would have held the heights.”

The night of July 1 was a time for critical decisions. Lee’s original plan to concentrate near Cashtown was discarded. He was inclined to take up a position along the north-south ridges running west of Gettysburg until Ewell was able to convince him that it made more sense to keep his corps as it was, spread across Gettysburg’s northern side. To sweeten the deal, Ewell anticipated that a key piece of high ground (Culp’s Hill) would soon fall into his hands, which would cut off one of the principal roads being used by the Union army. Lee allowed everyone to hold their positions for the night.

He had entered Pennsylvania anticipating he would fight a major battle, and while he may not have planned for it to happen at Gettysburg, he was also realistic enough to understand that a commander can’t expect to choose his arena. He arose early on July 2, half expecting to find that the Yankees had skedaddled. Not only was the Union army still on the high ground, but it was obvious that reinforcements had reached it during the night. Enemy units now occupied a line that stretched southward from Cemetery Hill along Cemetery Ridge.

Lee’s first encounter this morning was with James Longstreet. His First Corps commander proposed that the Confederates break contact in order to swing south to flank the enemy. The prospect of untangling Ewell’s men from Gettysburg’s north side and marching in vulnerable columns while the enemy gathered strength made Lee rule out Longstreet’s option. Although rebuffed in his attempt to change Lee’s mind about attacking the enemy at Gettysburg, Longstreet left their conversation convinced that Lee had not absolutely ruled out a flanking option.

In later years, Southern writers anxious to promote an image of Lee free from any failures of judgment insisted that he had issued Longstreet orders for an early morning attack, which the sulky corps commander ignored. Histories appearing as late as the 1960s accepted this as a matter meriting discussion. Yet it is clear that Lee could not have ordered such an action for July 2. When he awoke that morning, the exact location of the Union army was unknown. Until he could pin that down it would have been irresponsible to mount any offensive. Most modern historians give little credence to the “dawn attack” orders and the officers whose recollections support it.

[continued on next page]