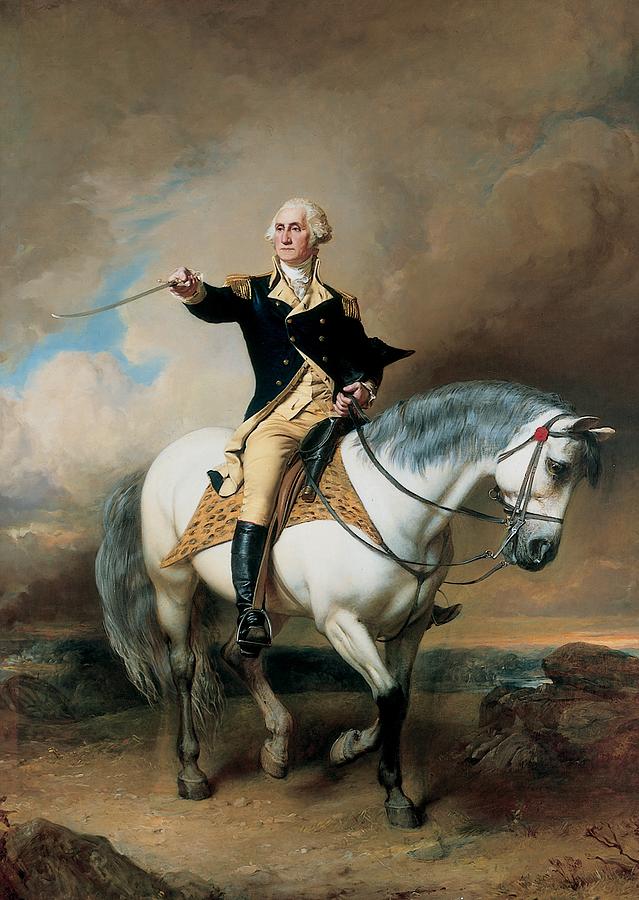

Surprising take on the Founding Father refutes historians’ view of him as an irregular commander

Yet another biography—but an ingenious one that posits George Washington’s greatest feat as being not military or presidential skill but guiding history’s most successful revolution. Historian O’Connell ends his narrative in 1783, and his scholarship breaks no ground, but few readers will object to this lively, opinionated account.

O’Connell’s Washington grew up a loyal British subject and minor scion of the Virginia aristocracy. No intellectual, he shared goals with fellow virile young southern gentlemen: get land, get rich, get military glory. By the time the colonies’ relations with Britain soured, Washington had gotten all those. Historians credit courage and self-promotion over talent for powering the service in the French and Indian War that made him a hero to colonists, a reputation that later served him well. Retiring in 1758, he spent the interwar years as a wealthy planter. Indebted, like most of his ilk, to British agents, he shared the widespread opposition to Britain’s post-1765 efforts to tax the colonies. In 1775, when the Continental Congress decided to choose a general to lead patriot forces, Washington made no secret of wanting the job. Other candidates promoted themselves, but he was the unanimous choice.

Some historians portray Washington as a leader of irregulars a la Fidel Castro or Josip Broz, aka Marshal Tito. O’Connell stresses that Washington saw himself as a European-style commander leading a disciplined army in the mass open-field maneuvers doctrinaire in 18th century combat. As such, he remained an aristocrat to the core. In a delicious irony, revolutionaries from Robespierre to Lenin to Mao were educated intellectuals who rationalized cruelty and murder as necessary for the greater good. Unschooled and middle-brow, Washington abhorred but nonetheless tolerated ungentlemanly conduct by his soldiers. Few rebel Americans objected to persecuting colonial loyalists. No law of civilized warfare applied to Indians. O’Connell, laboring at his point, passes over much bad patriot behavior. Yet there’s no denying that British troopers, steeped in brutalizing Irish rebels, treated Americans harshly.

A scholar must sweat to characterize Washington as a brilliant strategist, but it’s a no-brainer to conclude that he was a brilliant politician who managed a ragtag army through a violent revolution, enduring many defeats yet never, even in his lowest moments, unleashing the malevolence subsequent revolutionaries loosed. For eight years, he pleaded for support from a rattle-brained Continental Congress that responded with its usual bumbles. Generals from Cromwell to the current gang of military dictators took the obvious step, but Washington never considered it. Even at the time European observers considered Washington’s accomplishments of forbearance and performance as almost superhuman, and O’Connell makes a convincing case that they were right. —Mike Oppenheim writes in Lexington, Kentucky.