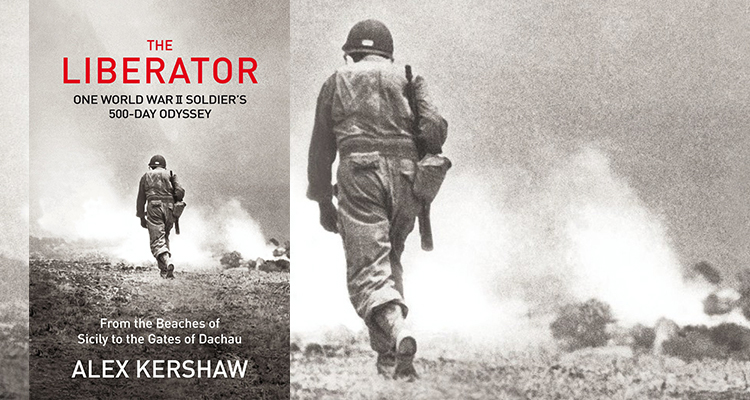

.jpg) The Liberator

The Liberator

One World War II Soldier’s 500-Day Odyssey from the Beaches of Sicily to the Gates of Dachau

By Alex Kershaw. 448 pp.

Crown, 2012. $28.

War is hell, but Felix Sparks, the central figure in The Liberator, learned the very hard way that hell comes in many forms. Sparks lived through sickening battles of attrition and the torment of seeing his men die in droves as his battalion fought its way through Sicily, Italy, France, and Germany. Then he discovered a whole new kind of evil when he reached a concentration camp called Dachau.

Bestselling author Alex Kershaw uses the combat-hardened Sparks to track the Seventh Army’s 45th Division, the Thunderbirds, during its long, bloody attempts to reach Germany from the south. Raised in Arizona during the hardscrabble Depression years, Sparks served a hitch in the army, left, and was drafted following Pearl Harbor, leaving behind a pregnant wife. Chafing at his role as regimental adjutant during the Sicily campaign, he asked for a combat command; he discovered he had a knack for battle, and preferred to be with his men at the front. Even after being wounded outside Ponte, Sparks insisted on returning to his unit for the brutal winter campaign in Italy.

The stalled Italian offensive, especially the carnage at the Battle of the Caves during the bungled aftermath of the Anzio landings, ushered Sparks deeper into hell: only he and one other soldier from his company survived. Promoted to command the division’s 3rd Battalion, Sparks found the invasion of southern France—“the Champagne Campaign”—to be a piece of cake in comparison. But enemy resistance stiffened as the Americans approached Germany. During the Battle of Reipertswiller in the Vosges Mountains, Sparks’s battalion, alone and exposed, fought experienced SS troops in the cold, snow, and ice, and suffered their first defeat of the war. Sparks called it his most tortured memory. Stunned by his losses—more than 600 of his thousand men—Sparks exchanged angry words with division commander Robert Frederick, who had refused to withdraw the battalion. In turn, Frederick vetoed a recommendation that Sparks receive the Distinguished Service Cross.

On April 29, 1945, Sparks received orders to liberate Dachau. At its outskirts, he and his men discovered boxcars filled with human corpses—“bodies stacked on bodies, waist-deep, stacked like cordwood,” Kershaw writes. The added horrors inside the camp pushed some of Sparks’s battle-weary men past their breaking points: they killed at least 17 of their SS prisoners being held in a coal yard. Sparks rushed back to the scene, firing his .45 into the air, and put an end to the killing. General George S. Patton later quashed an investigation. Kershaw’s account of this controversial and unsettling incident is even-handed yet compelling, particularly his depiction of Sparks, close to the edge himself, forcing a publicity-hungry American general to leave Dachau at gunpoint.

Kershaw’s accounts of the battles Sparks survived are clear and grisly and gripping. The terrors Sparks and his men endured in combat again and again prompt the question, how could they do it? The answer for Felix Sparks, as for many veteran warriors, was to turn off his emotions. “So long as he stayed numb, Sparks could fight,” Kershaw writes. Perhaps that’s why Sparks seems less of a fully fleshed-out individual than a somewhat shadowy guide, as Virgil was for Dante, on a harrowing journey—especially when he and his men grapple with the mind-bending enormity of what they find at Dachau. The Liberator is about war at the point of the spear, and it’s not pretty or reassuring. It’s hell.