A Complex Fate: William L. Shirer and the American Century

by Ken Cuthbertson (McGill-Queen’s University Press)

William L. Shirer had a tumultuous but celebrated career—first as a newspaper foreign correspondent, then as a pioneering radio broadcaster and, finally, as an authority on Europe. He spent seven years reporting from Berlin, 1934 to 1941, getting a virtually unmatched look at the rise of Nazi Germany.

As author Ken Cuthbertson explains in his richly detailed biography A Complex Fate: William L. Shirer and the American Century, Shirer was a competitive and astute journalist who suffered his share of career knocks, most notably when he lost his high-profile position as a CBS news commentator and later got unfairly labeled a communist sympathizer. He went 12 years without a job before reviving his fortunes, spectacularly, in 1960 when he produced his magnum opus, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. It became a huge bestseller, cemented Shirer’s legacy—and enabled him to keep writing until his death, at age 89, in 1993.

Born in Chicago in 1904, Shirer attended Coe College, where he was editor in chief of the school newspaper. After graduation in 1925, he and a friend worked their way to Europe aboard a cattle ship. In France Shirer wangled a job as a copyeditor with the English-language Paris edition of the Chicago Tribune and soon after was covering sporting events and celebrity doings on the continent. A front-page story on Charles Lindbergh’s landing at Le Bourget Airport got him a promotion, at age 23, to foreign correspondent for the Tribune’s Foreign News Service. Thus began a life of “gabardine trench coats and late-night trains.”

“Bespectacled, prematurely balding, and with his ever-present pipe clenched between his teeth, Shirer looked—and sometimes acted—more like an academic than a foreign correspondent,” writes Cuthbertson. He chased the news throughout Europe and beyond—even traveled to India to report on Mahatma Gandhi’s efforts to win independence for that country. The Tribune ran ads trumpeting Shirer’s scoops before the paper’s impetuous owner, Robert “Colonel” McCormick, sacked him for a couple of minor mistakes. In 1934 the Hearst-owned Universal News Service hired Shirer to run its Berlin bureau—the start of what he called his “nightmare years,” a phrase that became the title of a 1980 book.

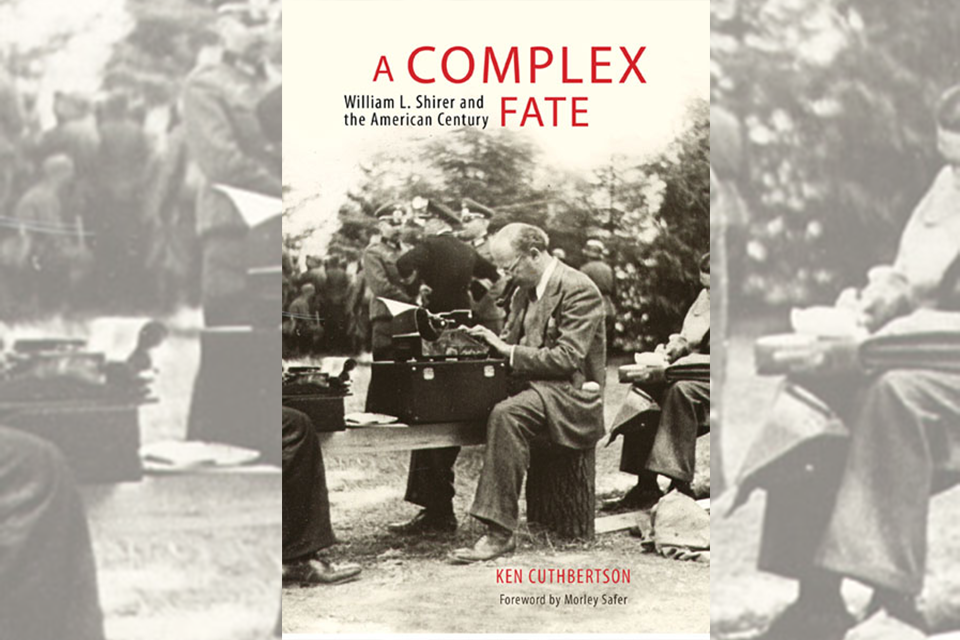

In 1937 Edward R. Murrow hired Shirer to help him start the CBS News radio network in Europe. Shirer was the first of the so-called “Murrow boys”—though Murrow biographer A.M. Sperber has written that the two men had a “unique” bond. Among all the CBS colleagues with whom Murrow worked, Shirer, by dint of his distinguished newspaper career, was his “only true peer.” In live, shortwave broadcasts to American listeners, Murrow and Shirer analyzed the Nazi takeovers of Austria and Czechoslovakia, the invasion of Poland, the Munich crisis. They built the foundation of CBS News, and in covering the war became stars. When the French surrendered at Compiègne in 1940, Shirer was there, sitting in a field amid the generals, tapping out his broadcast report on his trusty Royal.

Shirer returned to New York in 1941, wrote the bestselling Berlin Diary and became a CBS commentator. He had a sizeable audience, but by then he and Murrow had drifted apart. When Shirer’s sponsor, a soap company, dropped his program in 1947, CBS chief William Paley fired Shirer; Murrow, a company vice president, went along with the decision. Shirer never forgave Murrow for the betrayal. He struggled to earn a living for years before writing The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, followed by several other books, including a three-volume memoir. In a eulogy after the writer’s death, historian James MacGregor Burns noted that Shirer had “chronicled some of the most splendid and the most terrifying events of the [20th] century,” and “had shaped Americans’ views of Hitler, Gandhi and other important historical figures who had changed our world.” For a journalist, you can’t ask for more than that.

—Richard Ernsberger Jr.

Originally published in the December 2015 issue of American History magazine. Subscribe here.