‘You’ve been mighty brave so far!’ Mack called, his voice echoing through the bridge. ‘Whoever’s the bravest, come on across!’

Had Mack Marsden been living in Sacramento, Calif., or New York City in early April 1883, he could have read newspaper reports about his death at the hands of vigilantes. But Marsden lived in rural Jefferson County, Missouri, and the publisher of the local newspaper, the Jefferson Democrat, couldn’t bring himself to report that Mack had in fact narrowly escaped being hanged by the publisher’s own lynch mob. He didn’t run the story at all.

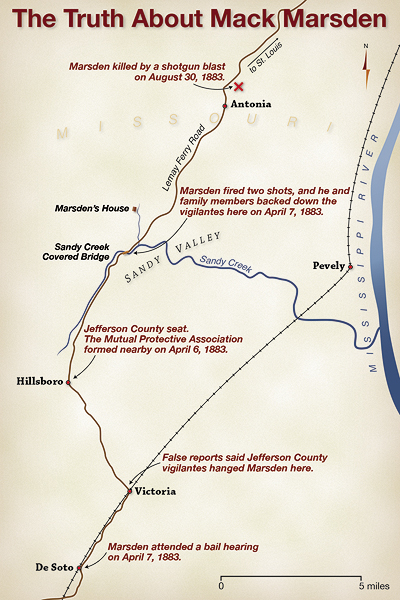

Marsden had just been bailed out of the county jail in Hillsboro, 40 miles southwest of St. Louis. So rather than worrying whether newsmen had botched the facts, he was likely just happy to be home with his wife and toddler son, tending to his livestock trading business. Perhaps he was also looking forward to playing baseball with his brother and friends. Mack pitched for the Sandy Valley team, and they’d be facing the Hillsboro squad that Saturday.

Matthew “Mack” Harrison Marsden seemed an unlikely suspect in the string of crimes of which he’d been accused. It all started one day in fall 1881 when he went to repay a loan from elderly recluse Anson Vail. The next morning Vail was found dead, his cabin burned down around him, with no trace of money in the ruins. Mack was tried for the murder but acquitted. After all, he had walked to and from Vail’s house in broad daylight and visited with neighbors—hardly the behavior of a killer.

Six months later, in the dark of night, someone set a store owner’s home in Antonia ablaze, and as the merchant, his family and other occupants escaped into the street, a hidden assailant shot and killed the merchant. Again Marsden was a suspect, as the store owner reportedly had evidence that Mack had killed old man Vail. Over the next year the papers published accounts of more arsons and stolen livestock, and Marsden’s name always came up when the Democrat ran the stories. Though arrested many times, he was never convicted.

Perhaps Mack should have been more concerned about the sinister picture the press was painting of him and where it might lead, though his father, Samuel, was upset enough for both of them about the sloppy, often biased and sometimes downright fictional work of journalists. He complained repeatedly to R.W. McMullin, owner, publisher and editor of the Democrat, about the accusations aimed at Mack. Sam said the ones behind the crime wave were his brother’s illegitimate sons, John and Allen Marsden. Regardless, McMullin printed that Mack was the leader of a gang, that various crimes “were laid at his door,” and that the community “breathed easier” when he was in jail.

Given that kind of opinionated reporting, it was no surprise when McMullin organized the Jefferson County Mutual Protective Association—in reality little more than his personal band of vigilantes. Dozens of mostly farming men met on Friday, April 6, 1883, in a barn outside the county seat of Hillsboro, under the glow of lanterns, and signed their oath to defend each other and rid Jefferson County of crime. McMullin wrote in the Democrat that the group was formed especially “to punish the hog thieves that have been plying their vocation in the neighborhood.” Even though the sheriff’s investigations couldn’t tie the string of crimes together, much less pin them on any one person, McMullin and his vigilantes were convinced Marsden was behind all of it.

In the weeks before formation of the Protective Association, Mack Marsden had been caught red-handed after selling stolen and easily identifiable pure white hogs to a St. Louis meat packer. Marsden admitted to selling the hogs, but he had a bill of sale and freely named the men who had sold him the hogs. Of course, those men were just as eager to testify that they had stolen them on Mack’s orders. So the whole bunch of them, including John and Allen Marsden, wound up in jail.

McMullin’s mob rode to De Soto on April 7 when the sheriff escorted Mack there for a bond hearing before a justice of the peace. Though several justices worked within blocks of the Hillsboro jail, someone had arranged for the hearing in De Soto, eight miles from Hillsboro and more than a dozen miles from Marsden’s home in Sandy Valley. It was all very suspicious. Mack would clearly be vulnerable during the long ride home, so his father, uncle and one brother rode along with the sheriff to protect the prisoner. People lined the streets of De Soto to catch a glimpse of the notorious Marsden. Among the onlookers were 50-odd men with concealed guns, and when Mack posted bond and left town, the mob readied for action. The Marsden party got about three miles out of De Soto when dozens of riders came over a hill in pursuit, a lynching rope at the ready. Both groups were off at a gallop in a thundering chase through fields, creeks and woods, past Victoria and Hillsboro, all the way to the covered bridge that spanned Sandy Creek. Mack knew his pursuers would have to slow down to funnel across the bridge, so as soon as he and his party had crossed, he cried out to the others, and they whirled their horses. The vigilante riders practically skidded to a stop as they looked through the bridge and down the barrels of the Marsden guns. Rumor had it Mack was never without his engraved, nickel-plated .32-caliber Smith & Wesson, and sure enough he fired two shots over the heads of the mob leaders.

“You’ve been mighty brave so far!” Mack called, his voice echoing through the bridge. “Whoever’s the bravest, come on across!” Nobody was that courageous, much less that foolish, so the chase ended in a standoff as the disheartened mob melted away.

A reporter (possibly from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch) had gone to De Soto to cover Mack’s bond hearing, but he had not bothered to join the pursuit. He’d already gotten wind of the Protective Association plan to lynch Marsden, and when the mob rode out after its prey, he remained in town. Perhaps nursing a beer, he imagined how the vigilantes would subdue the Marsden party, how long the rope was and how high the mob would hang Mack near Victoria, some four miles southeast of Hillsboro. So that’s what he wrote and sent out by telegraph. Within hours newspapers nationwide had adapted and embellished his fictional drama from the hills of Missouri. The Sacramento Daily Record-Union thought cows more interesting than hogs and ran the headline CATTLE THIEF HANGED BY MOB. The New York Times wrote, “Sturdy hands then seized the rope along 50 feet of its length, and at the signal, ‘All ready; go!’ the doomed hog thief and murderer shot up 10 feet in the air and hung until he was dead.” McMullin, of course, knew the mob had retreated in the face of Marsden’s revolver. But, having organized the Protective Association specifically to get Mack, the editor couldn’t bear the idea of reporting that in the Democrat. So he simply ignored the whole story.

The St. Louis papers, however, were widely read in Jefferson County, and McMullin was livid when the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported the story correctly, with details about how Mack backed down the posse. It even called the Protective Association riders what they were: vigilantes. After reading that, McMullin wrote a long editorial, scolding the Globe-Democrat and labeling its reporting of the attempted lynching “a mass of falsehoods.” He accused the St. Louis paper of trying to “incite our people to commit a grave crime, persuading them to mob Marsden.” Then he retold the story of the chase in a work of fiction that downplayed the attempted lynching, presenting it only as a few empty threats. “The so-called mob turned and fled to the woods,” the editorial concluded, “and that is all there was of it.” Only then, McMullin wrote, did the Marsdens go home and get their guns.

Ohio’s Newark Advocate ran the lynching story, but then courageously corrected it. MARSDEN THE HOG THIEF REPORTED LYNCHED STILL IN THE LAND OF THE LIVING, read its headline. “The account was related on all sides yesterday of how Mack Marsden, the ‘terror of Sandy Creek’ thief and murderer, had been hanged by a party of Jefferson County farmers, and details of the tragedy at the little hamlet of Victoria were told by those who claimed to have been with the vigilantes, and the account was sent off by telegraph. Today it is known that Marsden was not hanged, but that an attempt to lynch him failed.”

By the 1880s freelance reporters, like the one who invented the tale of Marsden’s lynching, were widespread, writing stories and selling them to telegraph companies, which sold them to newspapers nationwide. The more stories, and the more excitement they generated, the better the sales to a news-hungry nation. Stories often went to the highest bidder among competitors, like the newspapers in New York.

Any reporter could file a story on the wire and see it picked up nationwide. He was often the only one on the scene, with no one to contradict what he wrote, so he had little incentive to verify facts or interview multiple sources. Hurried reporters spelled names phonetically, and misspelled names often stayed that way. For example, the Sacramento story of Marsden’s hanging called him a suspect in the murder of “Valver Morey,” a bizarre misspelling meant to refer to Anson Vail. Many papers were weeklies, so anything reported in error could remain in print for some time. A person falsely accused might never find vindication. Also by that time the centuries-old hand-cranked printing press had given way to the rotary press, capable of printing thousands of copies per hour. Truth, lies and conjecture spread farther and faster than ever.

Some improvement in news reporting came with the advent of the Associated Press (AP), which started modestly in 1846 as a group of New York papers that agreed to share the cost of sending and receiving news. As years passed, the AP became the catalyst for journalists and publishers to take control of the news from the telegraph companies. The AP, not the telegraph companies, increasingly controlled the content and price, so coverage itself improved, though it remained far from perfect.

Some reporters of the era were careless. Others, like renowned New York journalist Joe Howard Jr., simply lied. For all his credentials, the colorful Howard was known for such stunts as using newspaper lines to transmit the genealogy of Jesus and fabricating stories just to elicit public reaction. In May 1864, as city editor of The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, he fed a false report to the AP, forecasting that the Civil War would drag on and that President Abraham Lincoln had called up 400,000 additional Union troops. In fact, it was a financial scheme, as the story spiked the price of gold, and Howard made a small fortune on gold he had purchased in advance. The editor sat in a federal prison for several months before the president pardoned him—perhaps in part because Lincoln later did call for another half-million soldiers.

Lousy reporting wasn’t always a bid for sensationalism. Newspapers used lots of ink to curry political favor, promote civic growth and make big men bigger. In 1884 the Neosho, Mo., Miner and Mechanic reported a case of horse theft, with poetic rambling about the beautiful set of matched dun mares that had gone missing. The celebrated livestock belonged to a leading citizen, whom the newspaper saluted along with some of his cronies. When news came from Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) that a U.S. marshal had recovered the stolen horses, the Miner and Mechanic added its own flourishes of how the marshal had engaged in a long-range rifle duel with the pair of thieves and dispatched one of them, while the other ran off into the woods to die. In Neosho the important thing was that the horses’ prominent owner got them back.

The real story came out in the Empire, published in nearby Pierce City, where veracity meant more than who owned the horses. Thinking to make good on their theft by selling the Missouri horses in the wilds of Indian Territory, the thieves camped at Tulsa. The next morning the U.S. marshal in Tulsa received a telegram describing the contraband horses. Following up on several leads, he soon caught up with the thieves about 11 miles outside of town. When he rode up to their wagon, pistol in hand, and told them they were under arrest, one of them pulled his pistol and fired twice. One ball struck the marshal in the wrist, while the other hit his horse in the head. At the same instant the marshal fired, killing the shooter. The other thief managed to jump from the wagon and slip away as the marshal lay pinned beneath his fallen horse. It was a thrilling story, certainly far more interesting than the color of the horses or worries of their wealthy owner.

Even then celebrities were worth their weight in movable type. Lawman and gambler Wild Bill Hickok was among the most chronicled figures in the West, and embellished tales of his daring and shooting skills abounded. Some were based in truth, but many were pure fabrication. Hickok didn’t seem to mind the notoriety or the exaggerations, until several newspapers reported in 1873 that he’d been killed in Fort Dodge, Kan., by a bunch of Texans. Bill couldn’t let that rest. He wrote to the St. Louis Missouri Democrat and other papers, protesting, “No Texan has, nor ever will, ‘corral William.’ I wish you to correct your statement.” Lest he offend the St. Louis editors, he added that the Missouri Democrat had been his favorite paper “since 1857.”

Missouri outlaw Jesse James also wrote to newspapers. In 1870 he addressed a letter to Missouri Governor Joseph W. McClurg, protesting his innocence after news reports accused him and brother Frank of robbing the bank in Gallatin, Mo. The Liberty Tribune, in Clay County, Mo., published the letter, in which Jesse insisted, “I can prove, by some of the best men in Missouri, where I was the day of the robbery and the day previous to it, but I well know if I was to submit to an arrest, that I would be mobbed and hanged without a trial.” He cited the case of Tom Little, a fellow Missourian arrested for a robbery he didn’t commit only to be hanged by a lynch mob. James had good reason to fear that crusading newspapers could turn the population against him.

Little more than a year after Bob Ford assassinated Jesse James, Mack Marsden and family faced down R.W. McMullin’s Mutual Protective Association in their classic standoff at the Sandy Creek covered bridge. Within weeks John Marsden, Allen Marsden and everyone else accused in the hog thefts were out on bond. John and Mack exchanged threats, tensions rose, and they and others brawled on the streets of Hillsboro.

Then, on August 30, 1883, along a remote stretch of the road to St. Louis, a shotgun-wielding assassin killed Marsden and a companion. With that, the mystery deepened. Had Mack’s notoriety in the press finally inflamed some civic-minded citizen to murder? Had lawmen or members of McMullin’s Protective Association killed him? His family claimed that the murderers, and true hog thieves, were John and Allen Marsden, who were determined to keep Mack from testifying against them.

County officials arrested John and Allen Marsden and two others on murder charges, but the men all had alibis and were either released or acquitted at trial. That was the end of the matter, as far as the law was concerned. The biggest question of all, whether Mack Marsden was truly the mastermind behind the Jefferson County crime spree or an innocent businessman framed by criminal relatives, was never answered.

None of the papers seemed to care who was behind the thefts and murders. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported “a feeling of thankfulness” at Mack’s death. “Outside of the natural curiosity,” it added, “there is no great desire to ascertain who the public benefactors are or avenge the death.” The St. Louis Globe-Democrat dubbed Marsden “the desperado of Jefferson County.” The New York Times wrapped up its coverage with the headline MACK MARSDEN, THE TERROR OF JEFFERSON COUNTY, SHOT AND KILLED. Such copy sold papers, and so the power of the press left its indelible mark on a man never convicted of a crime.

Author and songwriter Joe Johnston lives in Nashville, Tenn. He adapted this article from his 2011 book The Mack Marsden Murder Mystery: Vigilantism or Justice?