[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n a White House Rose Garden ceremony on October 5, 1981, President Ronald W. Reagan signed Public Law 97-54, a joint congressional resolution that, for only the second time in history, extended honorary citizenship to someone born outside the United States. A refugee from World War II Hungary had introduced the resolution a few months earlier. Representative Thomas P. Lantos, the only Holocaust survivor to serve in Congress, had recently been elected to his first term; the first bill he proposed was to honor the man who had saved his life.

That man was a Swedish diplomat who, in Budapest in 1944, saved not just the life of Tom Lantos but of tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews in one of the greatest humanitarian feats in history. But the guest of honor was not present, his fate a mystery. “What he did, what he accomplished was of biblical proportions,” the president noted. “Wherever he is, his humanity burns like a torch.”

His name was Raoul Wallenberg and his life was one of remarkable triumph and terrible tragedy.

RAOUL GUSTAF WALLENBERG was the scion of one of Sweden’s most powerful and richest families. The Wallenbergs were bankers, politicians, bishops of the Lutheran church, diplomats, and industrialists, with immense wealth and influence not only in Sweden but throughout Scandinavia. Founded in 1856 the Wallenberg empire is believed as late as 1990 to have indirectly controlled as much as one-third of Sweden’s gross domestic product. Given the family’s stature it is ironic that the most famous Wallenberg of all had no role in the family business.

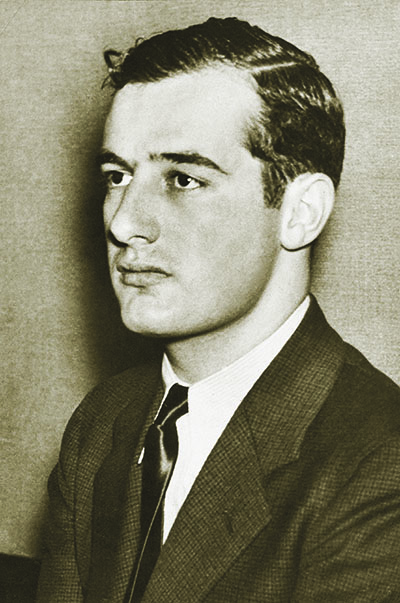

Born in August 1912 to a recent widow (his father, a naval officer, had died of cancer three months earlier), Raoul Wallenberg was an enterprising young man with a great curiosity about the world and a gift for languages. In 1930, having earned high marks in drawing and Russian, Wallenberg graduated from Sweden’s equivalent of high school. Sweden required its young men to complete nine months of military training; Wallenberg followed that with a year at France’s University of Poitiers, where he perfected French along with German, Russian, and English.

Traditionally Wallenberg men honed their education by attending an American university. While he could have sought admission to an Ivy League college, Raoul—with large brown eyes and dark, wavy hair that was already thinning—preferred the notion of attending a public university. In 1931 he enrolled at the University of Michigan, steered there by his grandfather to pursue a degree in architecture. “Wallenberg’s college friends remember a young man mature beyond his years,” one account notes: “funny, artistic, and with a rare gift for friendship.” To his grandfather Wallenberg would later write, “I am very impressed by America.”

Although he initially found life in Ann Arbor monotonous, Wallenberg loved everything about the United States and, a college classmate recalled, “seemed as American as could be—in his dress, in his manner and in the slang expressions that he quickly absorbed.” A sneaker-clad student who went by “Rudy,” the young Wallenberg had a fondness for hot dogs and movies—especially those of Charlie Chaplin, the Marx Brothers, and Laurel and Hardy.

Wallenberg used his vacations to hitchhike around the United States, working one summer at the World’s Fair in Chicago. Although armed gunmen robbed the intrepid traveler of $15 and left him in a ditch while he was hitchhiking his way back to Ann Arbor, the experience did not deter him. “I really didn’t feel scared,” Wallenberg later wrote; “I found the whole thing sort of interesting.” He continued to travel throughout the country in this manner, explaining to his grandfather: “You have to be on the alert the whole time. You’re in close contact with new people every day. Hitchhiking gives you training in diplomacy and tact.”

After graduating with honors in 1935 and winning an American Institute of Architects medal as the student with the highest scholastic standing, Wallenberg returned to Sweden, seeking but failing to find employment as an architect. His grandfather instead found him positions overseas, including at a bank in Palestinian Haifa—work unappealing to Wallenberg. “I think I have the potential to do something more constructive than sit around saying no to people,” he told his grandfather.

In 1938 he found a job and eventually joint ownership in an import-export company in Stockholm that traded in Hungary and central Europe, operated by a Hungarian Jew, Kálmán Lauer. With the rise of Hitler and, in Hungary, increasingly restrictive and hostile measures directed at Jews by the regime of Regent Miklos Horthy, Lauer found it difficult to travel. Wallenberg became Lauer’s trusted representative, learning Hungarian and, from 1941 on, traveling frequently to Hungary’s capital city, Budapest.

AS A GERMAN ALLY, Hungary had not been part of Hitler’s Final Solution during the early years of the war, and Jews throughout Europe fled there despite the country’s long history of anti-Semitism. By early 1944 Hungary possessed the third-largest Jewish population in Europe: 725,000, of which 250,000 resided in Budapest.

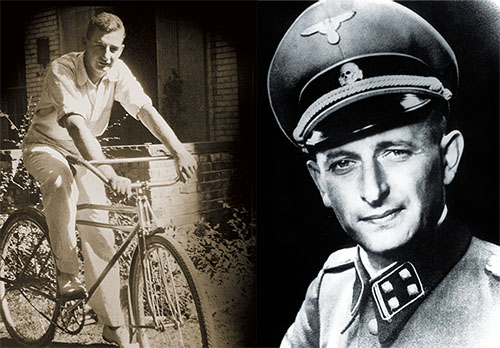

That March, aware the Hungarian government was making overtures to the Allies and considering it lax in dealing with its Jewish population, Hitler ordered the German army to occupy Hungary. With it came the angel of death, Adolf Eichmann, and his newly formed Sondereinsatzkommando special operations unit, to carry out the Final Solution on Hungary’s Jewish population.

The country was to be made “Jew clean” without delay. Mass deportations followed beginning in May, with as many as 12,000 men, women, and children a day packed into trains and sent to the death camps—most to Auschwitz-Birkenau in Poland. The massive numbers led the commandant to complain to Eichmann that processing 12,000 per day was severely overloading his crematoria. During the first two months of the purge, more than 437,000 Hungarian Jews had been deported. Later that year, with the Red Army nearing Budapest and Nazi Germany needing trains for higher-priority transport, Eichmann began sending his Jewish victims on death marches to the camps on foot. The brutality was beyond measure: those who could not keep up or fell were beaten and whipped, then executed, their bodies left on the roadside or tossed into the Danube.

THE UNITED STATES HAD BEEN SLOW to respond to the threat to the Jews of Europe but in early 1944 took steps to offer aid—help poised to arrive in Hungary later that awful year. At the urging of Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr., President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the War Refugee Board in January 1944. The board’s primary focus was the Jews of Hungary, by then the only nation where aid was still possible.

The War Refugee Board chose Iver C. Olsen, the financial attaché at the American legation in Stockholm, to carry out that mandate. Neutral Sweden still maintained diplomatic relations with Germany, which made travel to Hungary possible; Olsen’s task was to locate a suitable Swedish citizen to take on a humanitarian role there—someone with initiative and steely nerve, fluent in Hungarian and German, willing to “walk into the jaws of the Nazi death machine.”

Olsen had no luck finding anyone until he met Kálmán Lauer, who suggested Wallenberg. If ever a role was meant for one person and one person alone, it was Wallenberg’s impending mission to Hungary. For Wallenberg, then 31, the opportunity was enticing—a chance to do something truly meaningful.

The plan was for Wallenberg to go to Budapest as a diplomat. Olsen—who, as part of the clandestine Office of Strategic Services (OSS) station in Stockholm, had know-how in shuttling resources—would funnel American funds to Wallenberg through a Swiss bank. Wallenberg demanded that a number of conditions first be satisfied, the most important of which was that he would be his own man and, while attached to the Swedish embassy in Budapest, not answer to them; he also insisted on creating his own secure system of diplomatic cable traffic with Stockholm.

His conditions accepted, Raoul Wallenberg arrived in Budapest on July 9, 1944, bearing a Swedish diplomatic passport, two knapsacks, and an archaic revolver he had purchased in Stockholm. “The revolver is just to give me courage,” Wallenberg later told an embassy colleague. He would never use it.

Superficially the new first secretary of the Swedish legation, Wallenberg immediately set about making an imprint by establishing his own unconventional authority, hiring Jewish volunteers, declaring them and others under Swedish diplomatic protection, and telling them to toss away their yellow stars.

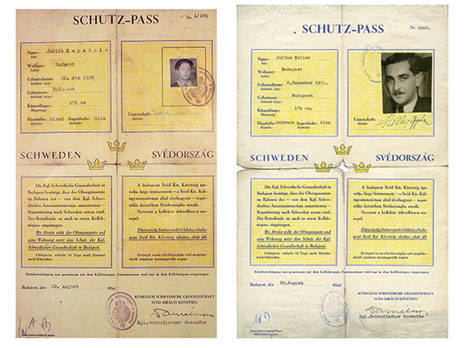

Within days, Wallenberg set in motion the widespread use of an official-looking safe-passage document he designed, the Schutz-pass—a type of Swedish passport that declared its holder immune from deportation to the death camps and under the protection of the Swedish government. It was all bluff. And it worked; Germans and the Hungarian Arrow Cross—thugs who modeled themselves after the Nazis—grudgingly accepted Wallenberg’s stamped, signed, and dated passes.

Day after day Wallenberg would hand out food, clothing, and passes and, in an authoritative voice, intimidate anyone who interfered with those under his protection. Although the exact number is unknown, Wallenberg’s Schutz-passes alone may have saved as many as 20,000 Jewish lives.

WALLENBERG USED EVERY WILE at his command to cajole, confront, or intimidate German and Hungarian authorities, nurturing contacts in the SS and Arrow Cross to increase his influence, sometimes softening his tactics with cognac and cigarette bribes. His best weapon was bravado and bureaucratic guile: the ability to wrangle concessions through compromise and negotiation, often without giving up anything in return.

His encounters with the German authorities inevitably brought Wallenberg into contact with Adolf Eichmann. Their exchanges were civilized, though Wallenberg’s diplomatic immunity was what saved him from seizure and certain execution. At one point Eichmann grew furious at Wallenberg’s use of the Schutz-passes and angrily exclaimed, “I am going to kill that Jew dog Wallenberg.”

On one occasion after Eichmann had begun the death marches, Wallenberg arrived in a convoy of International Red Cross trucks just as Eichmann was herding a group of several hundred Jews near the Austrian border, where a train awaited. Announcing in authoritative German that he was “Wallenberg, Swedish legation,” he demanded that Jews who had been issued Swedish passports get in the trucks. “I know I issued you a passport,” he told one. As the assembled Jews caught on, they proffered random documents and bits of paper, which Wallenberg swiftly gathered. He was able to save only several hundred of the 3,000 Eichmann had amassed; to those he had to leave behind he said, “I am sorry. I am trying to take the youngest ones first. I want to save a nation.”

The next time he returned to the border, he went straight to the waiting train. “Get off this train. I issued you passports. Your names are right there in my book,” he told the people onboard—for effect opening a large black book, calling out common Jewish names, and going through the motion of checking them off. To the guards who barred his way he announced he had the permission of the Hungarian foreign ministry to remove his people from the train. Through this gigantic display of sheer audacity, he saved several hundred more.

Shortly later, Eichmann abandoned the death marches; the Arrow Cross had withdrawn its support and Austria complained of being overburdened. Instead he followed the model of Warsaw and established a Jewish ghetto in Budapest, corralling some 60,000 of the estimated 90,000 to 124,000 Jews there. Many of the remainder found sanctuary thanks to Wallenberg who, using War Refugee Board-supplied funds, put his architectural training to practical use. He rented 32 buildings, mounted them with Swedish flags and declared them extraterritorial under the protection of Swedish diplomatic immunity, and somehow managed to cram some 10,000 people into buildings designed to hold only a fraction of that number, making the Swedish government the largest landlord in Budapest.

He also opened a hospital and an orphanage that housed some 79 children. “Hardly was there a day when he did not visit them,” one of the young women who worked on his behalf later wrote. One day Wallenberg arrived back in Budapest after a rescue mission elsewhere to find that the Arrow Cross had massacred all the children but one. “This was the first time we saw Raoul really desperate,” she recalled. “He went down on his knees and cried.” And vowed to press on.

By the end of 1944, the Red Army had Budapest almost completely encircled, the German army in full retreat. “The Russian advance has increased the hope of the Jews that their unfortunate plight will soon end,” Wallenberg wrote. Adolf Eichmann, who had sworn to fight to the end, instead slipped out one night, leaving incomplete his job of eradicating the city’s Jews. As Wallenberg biographer Kati Marton notes, Eichmann, who once boasted that he would go to sleep at night counting dead Jews, had met his match. “It may have been only then that it occurred to Eichmann that Raoul Wallenberg was, in his way, as skilled a technician of survival as he, Adolf Eichmann, was of genocide.”

WALLENBERG DID INDEED OUTLAST Eichmann, but a new and more dangerous enemy was about to shatter his life and take his freedom. With the arrival of the Soviets, Wallenberg believed he could play a role in the rehabilitation of Budapest and its surviving Jewish population. He did not seem to have grasped that he was dealing with men as ruthless and unforgiving as the Germans.

The morning of January 13, 1945, a Soviet patrol arrived at Wallenberg’s door, followed a short time later by several field grade Russian officers. Wallenberg insisted on contacting high Soviet authorities and was escorted to Russian headquarters. He returned the following morning to collect his belongings, telling his staff he expected to be back in about a week. Instead he was detained, never again to be seen in Budapest.

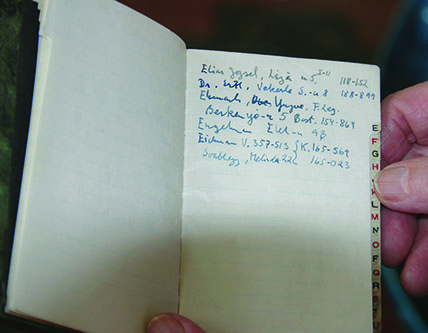

Wallenberg had become the latest victim of Stalin’s infamous penal system. There are various explanations and much speculation about why the Soviets seized Wallenberg; his ties with senior Nazis may have raised suspicion that he was collaborating with Germany or the Arrow Cross; several phone numbers for Adolf Eichmann appeared in Wallenberg’s address book, which the Soviets seized. Or they may have believed him an Anglo-American agent—a suspicion all the more likely if they knew of the OSS ties of his paymaster, Iver Olsen. Wallenberg’s actions certainly weren’t those of a typical diplomat. Whatever the reason for the envoy’s detention, his subsequent fate remains hidden in the tangled web of Soviet lies, cover-ups, and deception.

For decades after World War II the Soviets claimed they had no record of Wallenberg, only to later say he died in prison. It’s just as likely he was executed—when or where remains unknown. Despite international pressure in the more than 70 years since the end of the war, Russia has continued to stonewall about revealing what happened to Wallenberg. The only certainty is that he was arrested and detained on orders from someone very high in the Soviet hierarchy, possibly Stalin himself.

The Swedish government, reluctant to provoke the Soviets in the immediate postwar years, made somewhat ineffectual efforts to prod them over Wallenberg’s fate—producing denials that he was ever in Soviet custody and then, in 1957, the claim that, yes, he was, but that he had died of a heart attack on July 17, 1947, and been cremated. Other people claimed to have seen him in Soviet prisons or labor camps after that, but their accounts, like the other information, could never be verified.

Wallenberg’s mother and stepfather, Maj and Fredrik von Dardel, worked tirelessly to learn of his fate until, elderly, exhausted, and heartbroken after years of fruitless effort, they died by suicide just days apart in February 1979—first asking that their children not give up the fight to find Raoul.

The mystery deepened in April 2010, when archivists for the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) revealed that a man known only as Prisoner Number Seven—interrogated on July 23, 1947, six days after the Swedish diplomat’s presumed death—“in all likelihood” was Wallenberg. As before, no solid evidence emerged to back up the claim.

In 2015, to bring a measure of closure to years of dashed hopes and despair and allow for the settlement of his estate, his surviving family asked the Swedish government to formally declare Raoul dead. But before Sweden did so—in October 2016—another twist emerged. Newly uncovered diaries of a KGB chief said that Stalin himself had given orders to “liquidate” Wallenberg, and that he had been executed in 1947. In July 2017 the Wallenberg family sued the FSB for access to documentation about his fate; a Russian court has agreed to hear the case.

With the passage of so many years since his incarceration, though, it seems likely Wallenberg’s fate will remain a mystery. The ultimate irony of his imprisonment is that this man of peace should have paid such a terrible price for his humanitarian efforts. Although we can never know the exact number, Wallenberg’s acts of bravery may well have saved as many as 70,000 or more Jews from certain death in the hell that Budapest had become in the war’s final, bloody days.

What made Wallenberg so extraordinary—beyond his unbounded courage and utter disregard for his own safety—was that his mission in Hungary managed to revive hope in people who believed they had no future. In 1985 U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Jeane Kirkpatrick said of Wallenberg that he “has become more than a man, more even than a hero. He symbolizes a central conflict of our age, which is the determination to remain human and caring and free in the face of tyranny. What Raoul Wallenberg represented in Budapest was nothing less than the conscience of the civilized world.”

During some of the darkest days in the history of mankind, the deeds of one remarkable man stand out as a testament to the good angels of humanity. ✯

This story was originally published in the December 2017 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.