Bernarr Macfadden walked around New York City barefoot so his soles could absorb the earth’s magnetic forces. He slept on the floor so his blood would be able to flow according to its natural magnetic rhythm. He exercised his hair follicles by rhythmically yanking his mop, producing a disheveled appearance to match his threadbare suits. Guards at a Manhattan office building once barred him from entering until they realized that he owned the place.

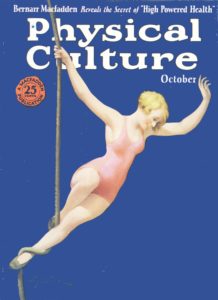

Macfadden made millions selling Americans on his eccentric theories about health. He created Physical Culture magazine, formed the Macfadden Institute of Physical Culture, and opened the Physical Culture Hotel, whose lobby featured a statue of Macfadden naked. He founded Physical Culture City, a New Jersey town that banned phenomena its proprietor deemed unhealthy—alcohol and tobacco, doctors and medicines.

“Medicine has had its day,” Macfadden said. “It belongs to the ignorance of the distant past.”

Born Bernard Adolphus McFadden on a Missouri farm in 1868, he was orphaned at 11, then apprenticed to a farmer who worked him mercilessly but made him strong. After two years, he ran away, hopping freights to work on farms and construction sites. He pumped iron, wrestled, and boxed. At 18, he opened a gym in St. Louis, billing himself as a “kinestherapist” and “teacher of higher physical culture.”

Hungry for fame and riches, he moved to New York. But first he changed his name. “Bernarr” sounded like a lion’s roar, he explained, and “Macfadden” set him apart from America’s many prosaic McFaddens. Reborn, he opened a Manhattan gym decorated with photos of him posing as Hercules, and taught wrestling and physical fitness. In 1899, he debuted Physical Culture, featuring articles by him illustrated with photos of his ripped form, nearly nude. He coined the magazine’s motto: “Weakness is a crime; don’t be a criminal.”

Macfadden’s magazine propounded his philosophy: vigorous exercise, fresh air, fruits and vegetables—and prolonged fasting, which he claimed could cure maladies from asthma to epilepsy. He crusaded against drinking, smoking, coffee, corsets, high-heeled shoes, vaccinations, medicines, and doctors, who he mocked as quacks. His goal, he said, was “the physical emancipation of the human race.”

His timing was perfect. America had entered one of its periodic fads for fitness. President Teddy Roosevelt was advocating “the strenuous life.” Muckrakers were exposing bogus patent medicines. Congress passed the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act. Men exercised with Indian clubs and medicine balls; women marched to ban booze. Macfadden sold millions of copies of Physical Culture and a women’s spinoff, Beauty and Health. He penned a novel whose weakling protagonist, thanks to the Macfadden method, becomes A Strenuous Lover.

In 1905, he rented Madison Square Garden for a “Monster Physical Culture Exhibition,” advertised with posters of muscular men and women, minimally dressed. Anthony Comstock, head of the Society for the Suppression of Vice, seized the posters and arrested Macfadden for obscenity. The court convicted him without penalty. The hoopla drew 20,000 customers.

Police again arrested Macfadden in 1907, when a New Jersey postmaster charged that a Physical Culture article about venereal disease was obscene. The jury convicted Macfadden; the judge sentenced him to two years in prison. He filed an appeal, meanwhile traveling the country denouncing prudes and censors. But the appeals court upheld his conviction. Facing prison, Macfadden urged fans to write to President William Howard Taft. Deluged with letters, Taft—America’s fattest president—pardoned the musclebound media king.

Macfadden loved sex. He married four women, cheating on all of them. His exercise regimen included a vacuum device designed to enlarge the penis. In 1913, lecturing in England, he offered a cash prize to “the most perfect specimen of English womanhood.” Hundreds of women competed. Swimmer Mary Williamson, 19, won; soon Macfadden, 45, had made her wife number three. The pair toured England, billed as “the world’s healthiest man and woman.” In performance, he lectured on his theories while she exercised in flesh-colored tights. At the show’s finale, he stretched out on the stage, wearing only a breechcloth. She climbed onto a high table and jumped feet first onto his rock-hard abs.

Mary bore seven children. The family followed the Macfadden fitness regimen—plenty of fruits, vegetables, and exercise, no doctors, no medicines. When their infant son Byron went into convulsions, Mary begged Bernarr to call a doctor. He refused, plunging the baby into a hot sitz bath. An hour later, Byron died in his mother’s arms. Macfadden tried to quash the story, lest readers lose faith in his wisdom.

Many readers valued that wisdom. Hundreds wrote him long letters, telling sad stories of romantic folly and seeking advice. A sampling published in Physical Culture proved so popular that Macfadden solicited reader stories for a magazine he introduced in 1919—True Story, which sold so well he ginned up True Romances, True Experiences, and True Detective. When letters from readers ran short, staffers banged out fictitious “true” stories. Nobody seemed to mind, least of all Macfadden. By 1930, he was worth $30 million.

To spread his ideas, the media mogul created the Bernarr Macfadden Foundation and published America’s most outrageous tabloid. The New York Evening Graphic specialized in sex, scandal, and violence, earning the nickname “the Porno-graphic.” The Graphic lost millions and folded in 1932 but achieved one goal—publicizing Macfadden, who decided he should be president. In 1935, he set up a campaign office, declaring himself “the perfect Republican nominee in 1936.” Republicans disagreed. In the 1940s, he ran twice for governor of Florida. In 1953, he campaigned for mayor of New York, promising to “purge the city of communists.” None of his campaigns succeeded. Macfadden Publishing stockholders sued him for spending $900,000 in company funds to run for office. Macfadden lost that suit and was ousted from the company he’d created and built. But he kept his foundation, and continued his proselytizing.

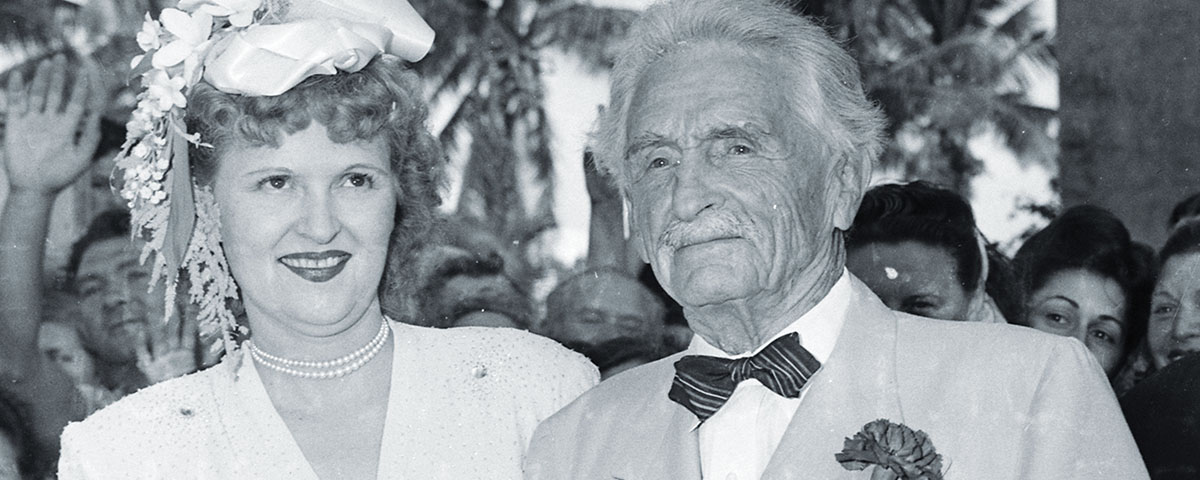

In 1947, he started a religion he called Cosmotarianism, preaching that people who took care of their bodies would go to heaven. Few disciples signed on. In 1948, at 80, he married Johnnie Lee, a 42-year-old fitness buff. Two years later she caught him in bed with another woman. He sweet-talked her into forgiving him. But when Johnnie again caught Bernarr en flagrante, she filed for divorce.

The fitness pioneer and genius publisher and promoter, found himself alone, broke, and—worst of all—ignored. Living in a seedy Jersey City, New Jersey, hotel, he was jailed twice for missing alimony payments. In October 1955, stomach pain drove him to fast for three days. He lost consciousness; the hotel manager called an ambulance. At the hospital, doctors—members of the profession he’d mocked for most of his 87 years—stuck him with needles and fitted him with a catheter. Within days, Bernarr Macfadden was dead of a urinary tract infection.