From the first ancient Chinese invasion to the final withdrawal of American troops from Indochina, the Vietnamese guerrilla resisted invaders with whatever weapons he could obtain, steal or improvise—even if it came down to a shovel and a knife. With those basic tools he could craft a fearsome weapon with multiple variations, all based on the punji stake.

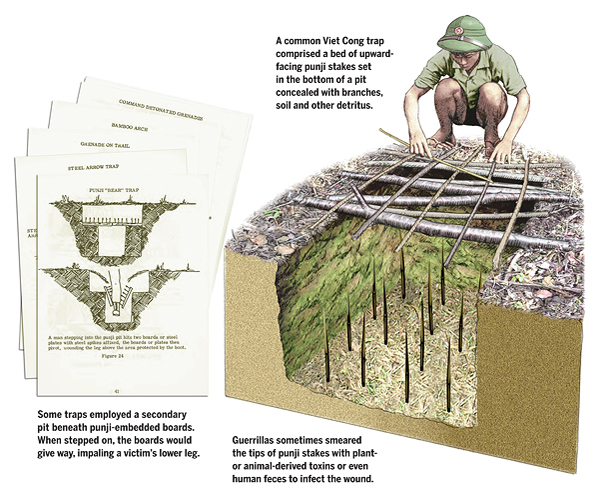

First to coin the term for the weapon were 19th century British Indian Army troops in the Punjab, in reference to native hunting traps. But it was the Viet Cong, the South Vietnamese communist guerrillas, who used punjis to their greatest notoriety a century later. Fashioning basic sharpened stakes from hardwood or bamboo, they would line well-camouflaged pits or trenches with dozens of punjis. They placed the traps around defended positions or in spots the enemy might seek cover during an ambush. They also placed more active traps, tripped by a hidden vine or wire to whip into and impale the victim. The stakes themselves were seldom fatal, but they could inflict painful, sometimes crippling injuries. This was in keeping with the VC philosophy that a wounded enemy, in compelling several comrades to evacuate him, removed more adversaries from a fight than a dead foe, who might go unattended until after the battle. Simple yet insidious, the punji stake was a harassing weapon that required extra vigilance and added to the misery of many a foreign invader of Vietnam’s forests and deltas.