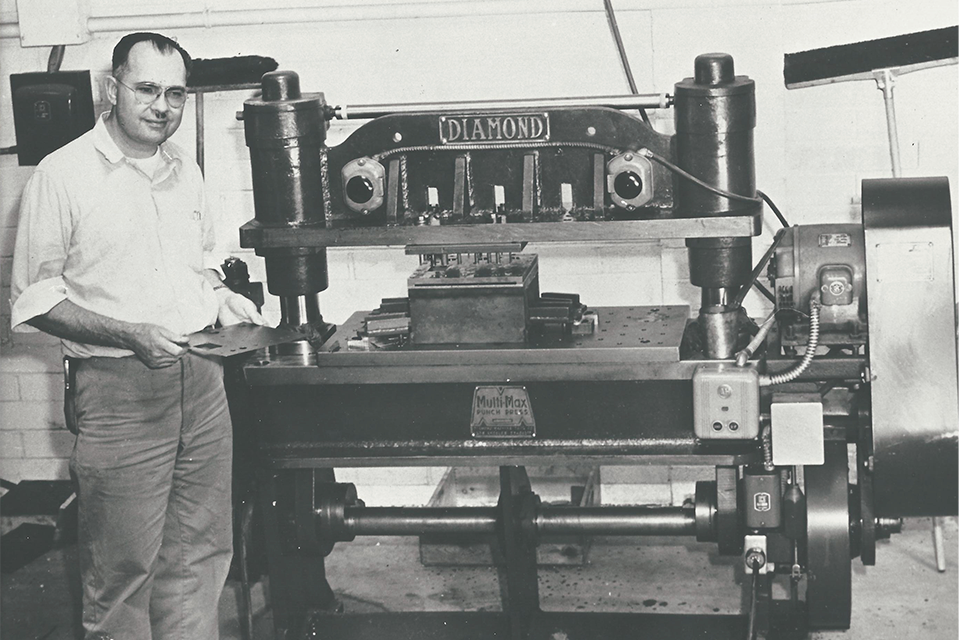

Leo Fender’s rhythmic innovation powered the music of a generation

LEO FENDER HAD LONG BEEN recognized as a wizard of musical technology whose name became a brand, and whose gear powered countless bands. Fender most truly innovated in creating the Precision Bass, which in rock ’n’ roll settings quickly supplanted the upright bass. Among innumerable players with whom the “P bass” found favor were legendary studio musicians Carol Kaye and James Jamerson.

The Fullerton, California, entrepreneur was key to the electric guitar’s birth. In the early `50s he had a hit with the Telecaster, a solid-body six-string able to stand out in a crowded dance hall. Now Fender was pondering how to enable musicians in electrified combos to achieve what acoustic bass players historically had done for unamplified bands: deliver a compelling layer of rhythm.

The upright bass—most players used a 3/4-sized version more than six feet tall—was difficult to play, demanding not only strength to hold down and pluck 1/8”-thick strings, but also musical training or at least strong intuition. A musician had to know just where on the long fretless fingerboard to put a fingertip and produce the correct note. The big wooden box, sometimes called “the doghouse” for its bulk, was all but essential to most music because it knitted together the sound. On a standard 88-key piano there are 19 keys—nearly two octaves—below the lowest E note on a standard guitar. The guitar bottoms out at 82 hertz. However, humans can hear down to about 20 hertz. At these sonic depths, notes solidify into percussive thumps that give music power. A mezzo-soprano singing an aria won’t get folks dancing, but a bass’s simple, deep, repetitive rhythm will.

In modern bands, the upright bass was getting lost among the saxophones, trumpets, and now, electric guitars. Bassists couldn’t even hear themselves—Fender often saw a player lean over to put an ear against his instrument, soaking up the vibrations through his skull. Notes on a bass fingerboard were farther apart than on those on a guitar neck. And the bass was awkward to transport, either stowed atop a vehicle in a canvas bag in hopes that it didn’t rain or taking up the entire interior so that a bassist had to drive solo while the rest of the band was yukking it up in another car.

Out one evening for Mexican food with wife Esther, Leo Fender was listening to the restaurant’s mariachi band when he focused on the musician playing a six-stringed bass instrument he held like a guitar. Watching the mariachi and his big-bodied guitarrón, Fender realized a guitar-shaped electric bass would solve a lot of problems. Players easily could adjust to the design, and be free to dance and move around, and if a bass guitar had a solid body and frets like a Telecaster, it could be thin and light and, driven by its own amplifier, get as loud as a player wanted.

Fender spent two years coming up with the Precision Bass, a name he chose “due to the fact that it is fretted and leaves no guesswork as to where the notes fall.” The Precision looked different from any instrument on the market, like something from a science fiction movie. Leo had wanted the Precision to balance horizontally whether on a player’s lap or hanging from a shoulder strap. To distribute the weight, he and assistant George Fullerton created a body with two horns curving out on either side of the neck, like flames on a hot rod. Other details, like the chrome knobs and bridge cover, the translucent yellow finish and black pickguard, came straight from the Telecaster. For lack of anything to copy, Leo and George lost much sleep and endured many headaches. The result was Fender’s most original creation.

Unveiled at a summer 1952 trade show, the Precision met with derision. Industry onlookers “were convinced that a person would have to be out of their mind to play that thing,” a Fender salesman said. An industry magazine, beneath the headline “Portable String Bass Really New,” wrote, “Obviously, the new bass is a big departure from the standard type of bass, as it is only one-sixth the size and is played in the same position as a guitar.” However, the Precision’s portability and durability, and the fact that a bassist playing one could place a fingertip in the same place as on a guitar and get the same note, only an octave lower, converted many doubters. Jazz writer Leonard Feather’s enthusiastic coverage and endorsements by bassists like Roy Johnson of Lionel Hampton’s big band built demand for what musicians initially called “the Fender Bass.” In 1954 Fender brought out a second electric guitar based on the Precision body. The Stratocaster cemented the shape into the popular imagination. By the 1960s the P bass had become a fixture onstage and in recording studios.

One day in fall 1963, Carol Kaye, a session guitarist, arrived for a recording date at Capitol Records on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles, California. As usual, Kaye nudged her Impala into a parking space barely ten minutes before the session and wearily opened the Chevy’s trunk. In it were the half-dozen instruments a session picker was expected to have: an Epiphone hollow-body electric guitar, a solid-body Fender Jazzmaster, a 12-string acoustic guitar, and a six-string Danelectro electric bass, plus an amplifier. Carrying her amp, a guitar,

and the Danelectro, which she often used in tandem with another bassist playing a Precision, Kaye trudged in, grabbed a cup of vending machine coffee, and looked at the session charts; another three-chord rock tune, most likely.

Kaye, the daughter of musicians, had amassed years of experience as an expert jazz player and guitar teacher. What she loved most was bebop, which took brains and fingers like nothing else; bop was to swing jazz what cubist painting was to classical portraiture—but improvised at a hundred miles an hour. By 1957, however, the hundreds of LA County jazz clubs where Kaye had earned her reputation as a picker had long since shuttered or been transformed into rock clubs. She had a choice: starve, move to New York, or play recording sessions. Kaye chose session work. Her first gig, at the invitation of storied rhythm and blues producer Bumps Blackwell, was backing Sam Cooke on “Summertime.” Kaye worked her way into a corps of elite musicians who performed anonymously on nearly every disc coming from studios around LA. Employing uncredited pros was standard practice. Producers weren’t about to let rock ‘n’ rollers, many of them still in high school, waste time and money with sloppy musicianship. They wanted experts who could read charts or invent clever parts, getting a song perfectly on tape in a few takes—even if in terms of talent it was like using a nuclear warhead to destroy an anthill, and in professional terms gigantically boring for aces like Carol Kaye.

Still, in 1963 Kaye, playing what she thought of as “idiot music,” was earning good money. As a member of the American Federation of Musicians, she made $63 for three hours in the studio, during which a good group might lay down four or five songs. She did have a lot on her mind, though. She had three kids and no luck with men. Her third husband loathed the fact that she spent many long hours and late nights working with musicians and producers who often were black men. Recently he’d smacked her son so hard with a rake the boy had had to skip school and see a doctor, which sent his mother tumbling into a nervous breakdown. Later, Kaye would remember nothing about that day’s session—except that the Fender bass player didn’t show, and the producer chose her to replace him. Someone put a borrowed Precision in her lap and told her to play any line she thought would work. She’d never really played a Precision, which had four thick strings instead of her Danelectro’s six skinny strings. The Precision’s neck was significantly longer than the Danelectro’s or an electric guitar’s, but Kaye played the session. Afterwards she drove to the corner of Sunset and Vine. At Fife and Nichols Music she bought two Precisions, then went straight home to practice on them.

Historically, the bass had played a supporting role, interlocking with the drums to form a rhythm section. Few songs came into the studio with written bass lines; session players were expected to invent them. Most studio bassists, electric or acoustic, did little more than plunk out single notes that went along with a song’s chords. But from that first session on a Precision, Carol Kaye saw that the electric four-string sat at a crucial juncture in the studio, offering a unique opportunity. The Fender bass linked the pure percussion of the drums to every other melodic element in the group. Sitting at the bottom of the studio mix, playing Leo Fender’s radical electric bass guitar, Kaye became the “bus driver,” as she thought of it—the one player besides the drummer everyone else had to follow. By playing electric bass, not only did she get to drive, but she often got to choose the route, calling on the melodic fluency she’d learned in jazz.

A few months after that first P-bass session, the benefits of Kaye’s helmsmanship were evident from the first moments of the O’Jays 45 “Lipstick Traces (On a Cigarette).” Kaye’s Precision drove the song. She locked into Earl Palmer’s drumming; the two seemed to meld into a single fat beat. Played with a heavy pick, the electric bass let her highlight every subtlety in the rhythm. Playing with such intricacy at such high volume would have been impossible on an upright. But the greater revelation was the way Kaye found to weave her bass line through a song’s melody. In “Lipstick Traces,” she painted variations in pitch that guided the singers, unifying groove and melody, rhythm and vocals, into a single movement. When she responded to what the singers were doing, the entire recording became more intense and athletic. Leo Fender’s Precision bass, in Carol Kaye’s hands, was helping to make music funkier, to make every layer of it more alive. She still played guitar on sessions, as on Phil Spector’s 1964 production of the Righteous Brothers’ “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling,” but it wasn’t like driving the bus.

A session musician’s job is to make songs into hits, and producers soon found that having Kaye sit in on bass increased a record’s chances of reaching the charts. She changed her listing in the local AFM directory, putting her name under “Fender bass” as well as guitar. Word spread that the former bebopper had a powerful new style. Soon Carol Kaye was the first bass player LA producers were calling for session work. Her rate for a three-hour session went to $104, then to $208. She left her husband, bought a house in LA’s Toluca Lake neighborhood, and hired a live-in nanny. Her main problem was getting enough sleep, what with all the work she was getting, such as from Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys, who was worried that his band might be getting obsolete.

Wilson, who’d chosen Kaye to play guitar on early recordings by his band, was himself a bass player, and an acolyte of Phil Spector. He wanted to work with someone who could execute his very specific vision of the bass’s role. Challenged by Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” and the Beatles’ album 1965 Rubber Soul, Wilson was pursuing a mature sound for the Beach Boys. Wilson made his old stage instrument, the Precision, now usually in Carol Kaye’s hands, a prominent part of his work. A prime example was “Sloop John B,” the first single from the 1966 LP Pet Sounds. The Beach Boys sang the opening lines a cappella, surrounded by flutes. Carol Kaye’s bass rumbled in with the drums, yanking the idyll into a torrent of sound. A Bahamian folk tune about a ship and its sailors became, in Brian Wilson’s composition, a refracted portrait of longing: “I feel so broke up/I want to go home.” Carol Kaye’s line followed the singers, seeming to identify with them, undergirding the rhythm but intertwining with their soaring melody. The song was impossible without her bass.

As Kaye was establishing herself as a first-call bassist in Los Angeles, halfway across the country another bass player had become essential to a project quite different from Brian Wilson’s aesthetic jousting with Bob Dylan and the Beatles. James Jamerson was a light-skinned black man with blue eyes and a mischievous smile. Born in Edisto, South Carolina, Jamerson was 18 when he moved with his mother in 1954 to Detroit, Michigan, where he played upright bass in blues and jazz clubs, also taking up the Precision. For Jamerson as for many Motor City jazzmen, club work led to session work in studios such as a basement operation fledgling music executive Berry Gordy had set up for his label, Motown. In 1964, Jamerson used his upright to conjure the warm, swinging throb of “My Guy” by Mary Wells, helping send that song to No. 1 on the pop chart—the “white” chart, not the ostensibly “black” R&B chart. Gordy decided Jamerson was too important to be allowed to leave and put him on weekly retainer. The label head was building Motown, also known as Hitsville USA, into “the Sound of Young America,” and he knew hits would come more easily with Jamerson’s grooves.

In his studio work, Jamerson seemed to refuse to accept the anonymity long assigned bass players. Soon after joining Motown, he switched from upright to a 1962 sunburst Precision that became known as “the funk machine,” famously never changing a string unless it broke. Keeping a technique dating to his days and nights on the upright, Jamerson plucked his Fender’s strings with his right index finger. He and the rest of the Motown house band, known informally as the Funk Brothers, went uncredited, but they and the singers they backed were being heard more than ever.

Three times in 1964 the Supremes put Hitsville USA at the top of the charts, with Jamerson’s bass more prominent on each tune. “Baby Love,” lifted by the cooing of Diana Ross, spent four weeks at No. 1 in the United States and England. On “Where Did Our Love Go,” the bassist locked in with the piano, building a rhythm so fine and airy it seemed self-propelled. Motown installed an eight-track mixing console that had Jamerson’s lines bouncing even more clearly through the chords to the Supremes’ “Come See About Me.” In 1965, for the

Temptations’ “My Girl,” Jamerson invented an unforgettable introduction, becoming more adventurous on a Supremes 45, “Stop! In the Name of Love,” another up-tempo No. 1. His signature restless style never remained still, underpinning the Four Tops’ No. 1 “I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch)”.

The output of Motown’s writers, producers, musicians, and stars, polished by company quality-control efforts, were achieving Berry Gordy’s ambition. By 1966 75 percent of Motown singles were entering the Billboard charts, compared with an industry average of 10 percent. From 1960 to 1969, according to critic and historian Jack Hamilton, Motown recordings charted at the astonishing rate of one every week and a half.

The Beatles adored the Motown sound, trying their best to copy it down to the intricate bass lines by that unnamed funk master. “It was [Jamerson], me, and Brian Wilson who were doing melodic bass lines,” Paul McCartney said later. “All from completely different angles: LA, Detroit, and London, all picking up on what each other did.”

The persistence of those Jamerson grooves carried a particular historic significance. For decades, black American musicians had innovated, while white players commercialized and profited. With a few exceptions, the American pop industry largely reflected the country’s sharp racial division. Labels, the press, and radio generally preserved a separation between radical adventurous new black sounds and safe, salable white sounds. Executives, parents, and politicians believed they had to protect white youth from black music. It was a commonplace in white industry circles that black stars couldn’t cross the color line to mass popularity. To make it to the very top of the music business, you pretty much had to be white.

Motown’s success changed that mindset. By 1966, this black-owned company’s black artists were dominating the once-white American charts—and not with one style or star, but with a rotating roster of Detroit performers and sounds. Unlike in earlier eras, when white imitators quickly covered and watered down black material, Motown’s output was less easy to co-opt, because Motown was an empire tightly controlling its product from tempo to arrangement to performers’ diction and deportment. Not every Motown release was a hit, and not every song was a classic, but in the label’s heyday, Motown conquered the white mainstream, and at its sound’s rumbling core was Leo Fender’s P bass in the hands of the brilliant James Jamerson.

_____

Editor’s note: Carol Kaye eventually worked more than 10,000 recording sessions and authored best-selling books on musical technique. She is the subject of the documentary First Lady of Bass. At carolkaye.com, she offers one-on-one lessons by Skype as well as her books, recordings, and videos. James Jamerson was 47 when he died in 1983 in Los Angeles of complications from cirrhosis of the liver. His towering reputation has earned Jamerson numerous posthumous accolades, including initiation into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and pride of place in Standing in the Shadows of Motown, a 2002 documentary about the Funk Brothers. —Michael Dolan

How many Precisions have you had? The Fender bass was my second instrument. When I went into studio work in 1957 to support my kids, I was a jazz guitarist, playing fills, rhythm, and lines for Sam Cooke and others. I accidentally got into Fender bass in 1963 when someone didn’t show up for a date. I liked inventing lines for rock, pop, and soul on bass better than playing guitar, so I bought two Precisions. In my busy years, I didn’t even have time to change strings, so every two or three years I’d trade in one Precision—to get new strings. I probably had five or six, and after 1976 two or three more. They weren’t great instruments but with good necks, pickups, and strings they got the job done. I don’t recommend Fenders today—except the Mexican-made Jazz bass, which is very good. I used other basses, too, but for the past 16 or 17 years I’ve stuck with the Ibanez 700 SRX.

What makes a successful bass line? A successful bass line has great time sense, makes a proper outline statement and answer, and supports the artist with structured lines and occasional fills while leaving good spaces. The bass congeals the band into a whole according to the arrangement—if there is one—or the tune’s style. Playing bass is not about you, it’s about making a difference by being on the bottom. You have to make everyone else sound great. Gelling with the drummer is a must—you’re the “note” connecting rest of the band.

Where do great bass lines come from? From your experience as a musician. Only the finest—top of the pile of union pros, especially those of us from the pre-rock worlds of jazz and big-band music—were chosen to be studio musicians. In jazz you invent every note you play according to what’s going on around you. This art is critical in studio work.

Do any of your riffs stand out for you? I have no favorites. It’s been thousands of lines—I did over 10,000 record dates and movie calls, which amounted to 40,000-plus songs and movie and TV cue lines.

What are you up to? I’m teaching jazz on Skype. I’ve written 48-plus bass and guitar courses, books, DVDs, and produced many CDs from my catalog. I love being able to pass along real musicianship. I enjoy hearing from former students and those who did well with my tutorials worldwide. I’m also enjoying music again. Studio musicians sometimes record 16 hours a day, so you like coming back to a quiet house to refresh yourself. But now I have music going at home—jazz, classical, standards, and older styles I grew up with—so much great music.

Does ego serve musicians? Unlike today, from the `40s through the `70s we never had ego. It’s dismaying to see selfish ego ruin so much natural music. It’s self-destructive. I’m hoping that newer generations learn from the mistakes of “me-me-me” and go for the music, as musicians used to do. That’s the joy—not showing off but immersing yourself in the music with no thought of yourself. Music is a healer; it’s life itself.

Read more about Carol Kaye at Deadline.com: “‘The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel’ Angers Bass Legend Carol Kaye: “My Life Is Not A Joke.”