At a Baltimore table in 1887, the discussion centered around Lee, Jackson, Stuart, and Longstreet

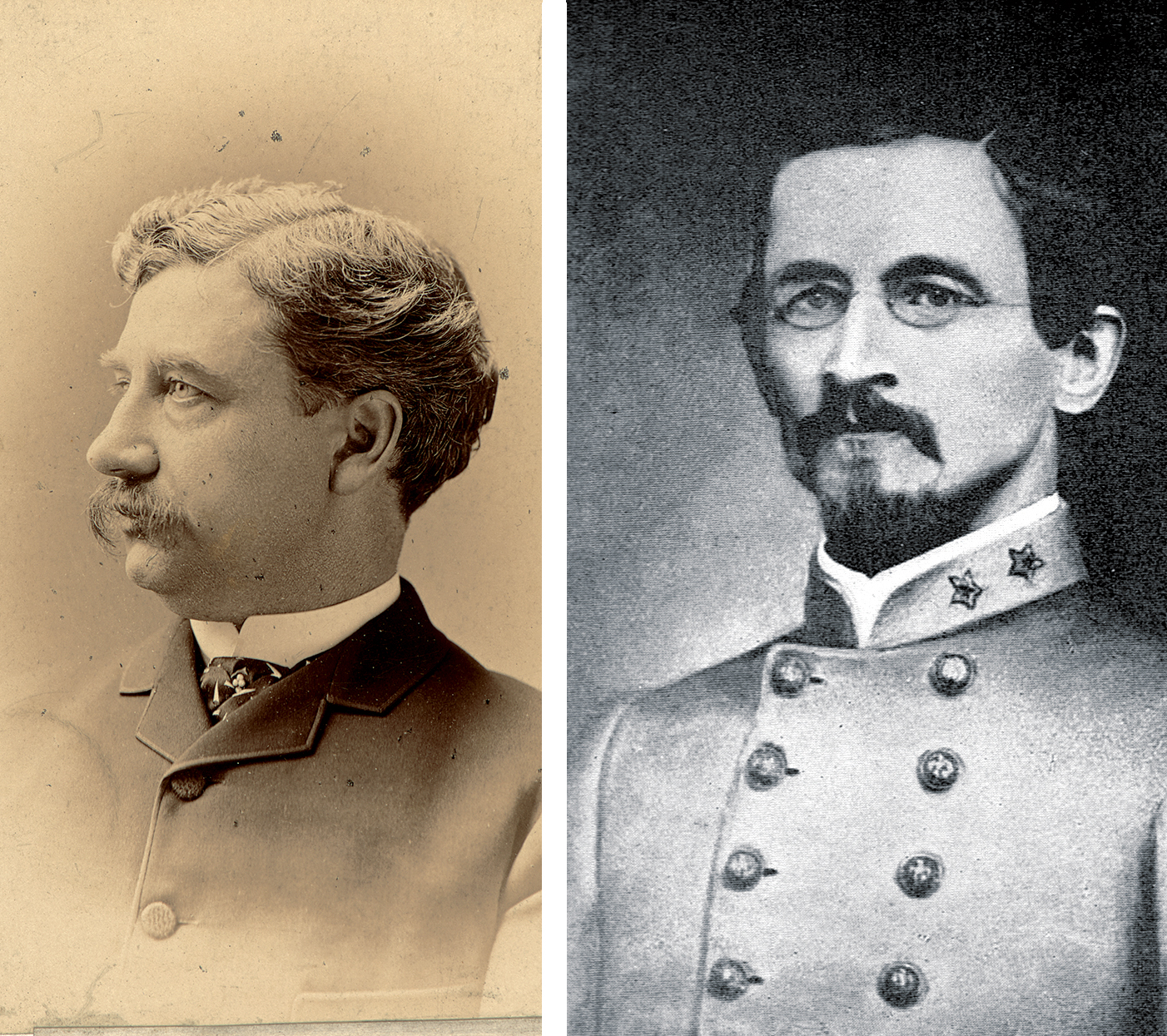

[divider]AUSTIN JOHN REEKS, born in England in 1840, carved out a Confederate career of exotic hues. Reinventing himself with a new name—Francis Warrington Dawson—the young man came to North America on a Confederate steamer, served briefly with the Southern Navy, then joined a Richmond artillery battery. By the late summer of 1862, the 22-year-old Englishman had landed on Maj. Gen. James Longstreet’s staff as ordnance officer. Serving in that high-level headquarters, Dawson witnessed the leadership of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at close range. His memoir, ably presented and full of insight, remains a classic in Confederate literature.

[divider_flat]Three years after his Reminiscences of Confederate Service reached print in 1882, Dawson published another significant book: Our Women in the War: The Lives They Lived; the Deaths They Died. The newspaper he ran, the Charleston (S.C.) News and Courier, had solicited accounts from Confederate women and published them steadily. Our Women reprinted 79 of the articles. Dawson’s name does not appear in the book, but his company obtained the copyright, and he signed many of the surviving copies. His own wife will be forever famous in her own right for her contribution to the literature of the war. Sarah Morgan Dawson’s Confederate Girl’s Diary remains a classic, still in print after more than a century. No other Southern couple published a pair of books that could approach that sort of cachet.

The book about Southern women prompted the Baltimore Confederate veterans’ organization—the Association of the Maryland Line—to invite Dawson to come up from Charleston and speak on that topic at its fifth annual reunion. Dawson delivered the address at the Academy of Music in Baltimore on February 22, 1887. Although the audience, being attuned to Victorian podium techniques, probably appreciated the address, the 20,000-word oration must have lasted for hours.

Two nights later, Dawson attended a dinner in his honor at which several other well-informed, high-ranking veterans discussed interesting and controversial topics regarding the Army of Northern Virginia. One of them promptly wrote extensive notes for the benefit of posterity. The late historian Lee A. Wallace Jr. found the notes years ago.

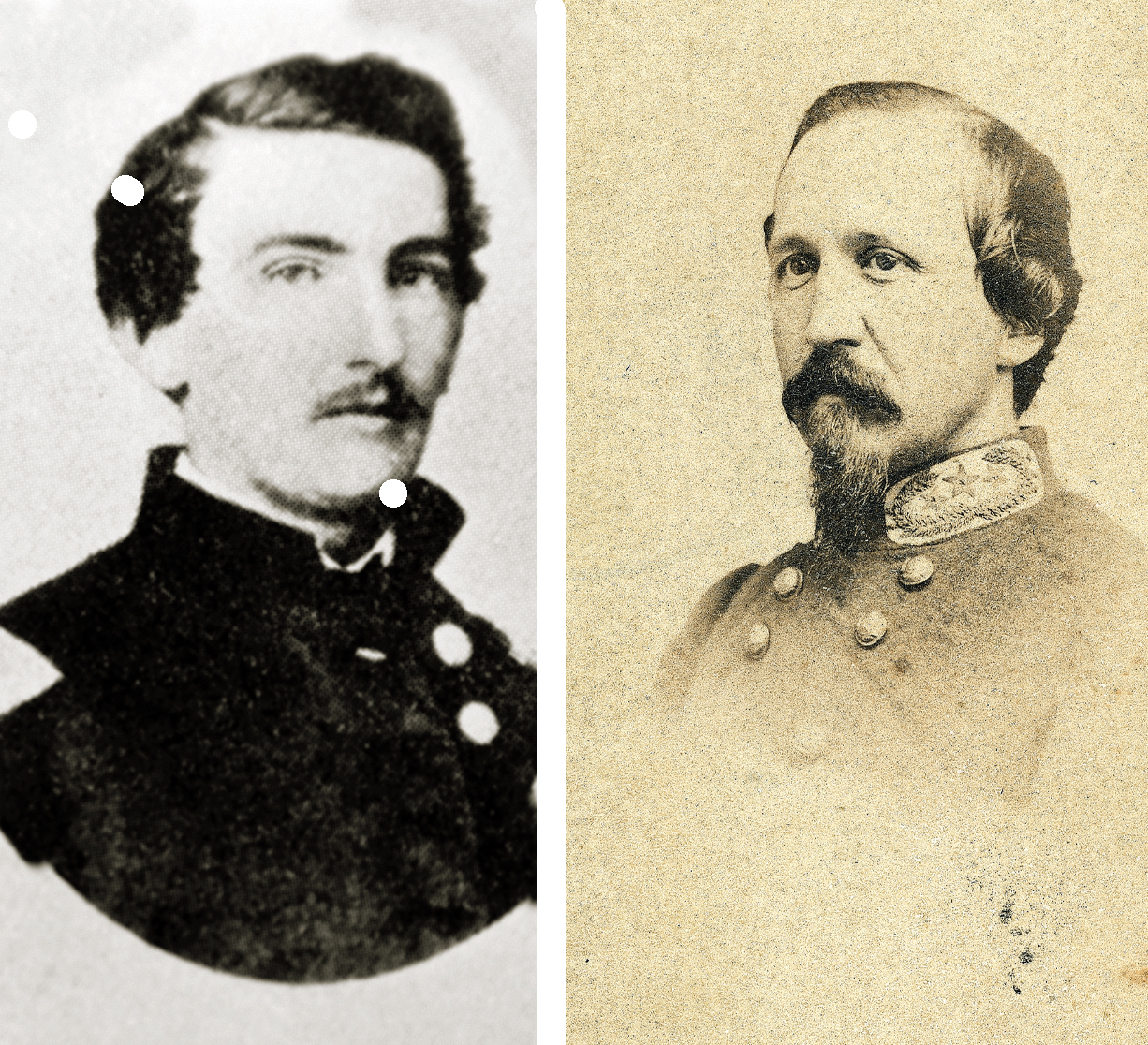

The scribe, Colonel David Gregg McIntosh, had led South Carolina artillery during the war, rising to battalion command. Modern collectors cherish his pamphlets about Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, but an even more important McIntosh document has not been published—a detailed narrative of a postwar trip to the Virginia battlefields bedizened by recollections of what he had seen at those sites during the conflict. The colonel’s wife, Virginia—a sister of Brig. Gen. John Pegram and artillerist Colonel William J. “Willie” Pegram—assured him of high social standing in Baltimore.

The scribe, Colonel David Gregg McIntosh, had led South Carolina artillery during the war, rising to battalion command. Modern collectors cherish his pamphlets about Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, but an even more important McIntosh document has not been published—a detailed narrative of a postwar trip to the Virginia battlefields bedizened by recollections of what he had seen at those sites during the conflict. The colonel’s wife, Virginia—a sister of Brig. Gen. John Pegram and artillerist Colonel William J. “Willie” Pegram—assured him of high social standing in Baltimore.

[hr]The dinner’s hostess, who despite two marriages often used her maiden name, Hetty Cary, had been among the brightest belles of the Confederacy, widowed after a very short marriage to General Pegram. A history of Richmond Confederate society called Cary “one of the most beautiful and most notable of all war belles.” Dawson told an amusing story about Hetty’s unmarried sister Jenny, who also attended the 1887 dinner, calling her “handsome” and admitting that “she was overshadowed by her sister.” Dawson quoted Jenny as saying resignedly “that the only inscription necessary for her tomb-stone would be: ‘Here lies the sister of Hetty Cary’.”

One of the four guests was Colonel Charles Marshall, who had taught at the University of Indiana before becoming a prominent Baltimore lawyer before the war, during which he served as an important member of Lee’s staff. His personal relationship with his chief made Marshall an important witness. At the dinner, Marshall discussed his memoirs, which would not appear in print until long after his death in 1902. Although valuable, those published reminiscences largely avoided controversy. Marshall’s dinner conversation in 1887 did not display any of that reticence!

The fourth prominent veteran around Hetty’s table that night, Brig. Gen. Bradley Tyler Johnson, contributed little to the vivid conversations, at least so far as McIntosh’s notes reveal. Johnson does not fit snugly with the profile of the rest of the group. He probably had enhanced his popularity by beating Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden savagely with a leather belt in the local train station a few years before. Perhaps Hetty and Johnson’s popular wife, North Carolinian Jane Saunders Johnson, were friends and that explained the invitation. Dawson mentioned Jane Johnson in his book, and later in his address, for her striking contributions during the war.

Hetty Cary had arranged to have at each seat, in lieu of a place card, a miniature satin Confederate flag embossed with the guest’s name. Discussions over dinner rambled across a wide spectrum of Confederate topics. Three themes loomed large: J.E.B. Stuart, especially during the Gettysburg Campaign; Lee and Jackson at Chancellorsville; and Lee’s relationship with Longstreet. Each of these themes, of course, still generates debate. McIntosh wrote about the two battles a few years later; perhaps this evening’s discussions launched those literary projects in his mind.

Memories of Stuart during the dinner focused on two familiar motifs: his colleagues’ deep affection for him, and the dreadful impact of his misguided excursion through Northern Virginia and Maryland during the Gettysburg Campaign. McIntosh’s notes report remarkably strong sentiments on both fronts. Lee “was excessively fond of Stuart,” Marshall said, adding that he was himself—Stuart being “a most noble, loveable man.” When Lee heard of Stuart’s death in May 1864, he leaned forward and put both hands over his face “for some time to conceal his emotion.” In recounting that scene, Marshall “became much moved as did those who were present.”

What he viewed as Stuart’s malfeasance en route to Gettysburg prompted Marshall to startlingly harsh comments. After the campaign, the staffer tried hard to have Stuart court-martialed for “explicit disobedience of orders.” Stuart dragged his feet about producing his report. Lee “said he must have it” and dispatched Marshall to see the reluctant cavalryman, who “gave me a first rate dinner…but he had no report.”

Lee’s own Gettysburg report has been parsed minutely by interested students and will be endlessly into the future. The first draft, written by Marshall as was typical, treated Stuart very critically. Lee, predictably, did not like the pejorative tone and softened it. In the most bitter remark over that 1887 dinner table, Marshall declared that he told Stuart in person that “I thought he ought to be shot.”

As grist for modern reexaminations of Stuart’s orders, route, and behavior, here is a summary of Marshall’s description of Lee’s instructions: The cavalry had orders “to move forward along our flanks.” Once the army crossed into Maryland and Stuart had not covered those flanks, the army commander sent him an “explicit” order, “on the most peremptory terms,” about the course of the march. In Marshall’s view, Stuart disobeyed that order egregiously, and admitted doing so.

When talk turned to Chancellorsville, Marshall revealed particulars about Lee’s health and on the commanding general’s famous last meeting with Jackson the evening of May 1, 1863. Just before Chancellorsville, Marshall noted, Lee suffered from a bout of pneumonia, “from which he never recovered.” Chest pains became so severe, in fact, that Lee “had to lie down on the road side.” Marshall kept a pistol in one saddle holster and a flask in the other, from which he made a drink of one teaspoon from the flask and a cup full of water. In “a moment or two” Lee got up and “felt greatly relieved.” The general “frequently” complained later of pain “and a stricture” in the same spot.

The story ended on a jocular note when the rest of the dinner party agreed that Marshall’s recipe for his own consumption would have been completely reversed, to one teaspoon of water in the cupful.

Marshall’s description of the final Lee–Jackson rendezvous included a striking historical tidbit. His mention of a map guiding the meeting stands out because the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park owns—and used to display—a crude map, apparently in Jackson’s hand, illustrating the route simply and vaguely. By the staffer’s account, Lee “produced a map” that showed the roads he wanted Jackson to use, saying that “his engineers” had examined them at his direction. Lee showed Jackson what he wanted using that map. In 1887, Marshall had the original artifact in his possession. Is it the one the Chancellorsville Battlefield Park and Visitor Center owned—and displayed—for years? Probably not, given the handwriting on the Jackson map.

The group fulminated against Longstreet. That is not surprising, given that Longstreet was in bad favor in the South after the war. Dawson, however, had been on Longstreet’s staff for several years, and treated him kindly in Reminiscences. By 1887, Dawson had become one of the most powerful and influential men in the South, with no reason to be at all timid about his positions. That makes his concurrence in the group’s criticism of Longstreet quite significant.

In his extended operations in Tidewater Virginia in the spring of 1863, Longstreet delayed returning to the Army of Northern Virginia far longer than Lee wished. His absence may well have made Lee’s success at Chancellorsville possible, considering he won the battle using risky initiatives that Longstreet surely would have resisted stubbornly. On the other hand, Longstreet’s force would have been a priceless asset during the battle.

Marshall described taking dictation of a Lee letter to Jefferson Davis “regretting in the strongest possible manner” the delay. The operations around Suffolk “were of a negative and useless character,” although Longstreet attributed to them “an importance…altogether fictitious.” About his much-mooted mood at Gettysburg, the assemblage—including his own staff officer—concurred in the “sentiment…that Longstreet’s heart never was in the…campaign.”

Lee’s custom of riding with Longstreet’s Corps and camping in its vicinity has prompted historians to suggest that the more convivial setting appealed to Lee, in contrast to Stonewall Jackson’s dour piety and Spartan arrangements. At the 1887 dinner, Marshall explained the choice of headquarters locations “when the army was moving,” in a different tenor. He quoted his chief as saying that when he wanted Jackson to execute a movement, he merely needed to send an order. When Lee wanted Longstreet “to do a thing,” by contrast “the safest way was to go along with him.”

In a scornful anecdote, Marshall derided Longstreet’s military acumen and style. After the war (and after Lee’s death, of course), the corps commander boasted of elaborate advice he had supplied to Lee; ignoring it led to defeat—at least through Longstreet’s lens. Marshall described just such advice, shared with Lee in writing, especially late in the war. “[L]ong written communications,” running to more than a dozen pages, came in from Longstreet, and Marshall would read them to Lee. At the end of one reading, Marshall “laughed aloud.” When his chief asked why, Marshall replied, “You know very well, General, why I laugh.” Lee chided his aide slightly: “You ought not to laugh…that bullet [that wounded Longstreet on May 6, 1864] in the Wilderness hit him very hard.”

The dinner invitations had carried with them instructions for each of the veterans to be prepared to “tell some personal reminiscence” during the evening, apparently on any topic other than the weighty military matters occupying much of the conversation. One tale involved bathing in a stream within sight of some sentries, who unexpectedly turned out to be Yankees. When the soldiers opened fire on the narrator, he fled in haste. Hostess Hetty “asked eagerly” what the bather had on. “Nothing” came the reply.

Charles Marshall talked more than the other guests that evening, or at least McIntosh recorded more of what he said. He offered several gently amusing tales about Lee’s avuncular treatment of his staff. One reported on an excursion he made carrying orders from Lee about dispositions along the Rappahannock. Changed circumstances by the time Marshall reached the riverside prompted him to change the orders on his own volition. He reported that to Lee when he returned, just as the headquarters establishment—including a distinguished visiting Englishman—sat down to dinner. Lee said nothing at the time, but during the dinner he told an elaborate story about a prewar officer who always changed the orders he carried, ostensibly for good reason. The aide in the proverb “made himself somewhat famous” for the bad habit and got in trouble for it; Lee’s audience, especially the Englishman, enjoyed the jape, Marshall less so.

In the same dry vein, Lee commented tardily and obliquely on a jug in his aide’s tent. Marshall and staff colleague Lt. Col. Charles Scott Venable were discussing a mathematical problem one evening. Venable, an accomplished mathematician, published a number of textbooks and had gone before the war on an astronomical expedition to the coast of Labrador. Marshall had just poured a drink from a stone jug into a tin cup when Lee pulled open the tent flap and looked in. He made no comment. The next morning at breakfast, Marshall recounted a fantastic dream from the night before. Lee remarked that “when a mathematical problem” needed solution, and the unknown quantities in the equation were a stone jug and several tin cups, “remarkable dreams” resulted inevitably.

After listening to Marshall’s stories, Johnson, McIntosh, and especially Dawson urged him to finish the “memoir” that he had been writing and publish it at once. Dawson insisted that it was “due to the truth of history.” Marshall admitted that the book was almost finished, but that he recoiled from publishing it because it would “hurt too many people.” In fact, he concluded, perhaps it ought never to reach print.

Marshall had been dead for a quarter-century when his written memoirs finally came out from Little, Brown and Co. in 1927, edited by a renowned British soldier. They remain a classic Confederate book, but are somewhat dry, without the snap and crackle of his remarks over dinner 40 years earlier.

Hetty Cary continued to run the girls’ school her mother had founded on Charles Street for a few more years, but died at age 56 in 1892.

Francis Dawson’s colorful life came to a bizarre end only a few months after the memorable dinner. In March 1889, a doctor who lived next to the Dawsons in Charleston seduced the couple’s young Swiss au pair. The miscreant murdered Francis when he tried to intervene and tried to hide the corpse under the floorboards. Nevertheless, the doctor went free and then declared buoyantly that his friends and clients surely would not abandon him over “this little indiscretion.”

Robert K. Krick, former historian at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, is author of The Smoothbore Volley That Doomed the Confederacy and Chancellorsville: Lee’s Greatest Victory.