‘Colossal Ambitions’ examines Confederate expectations for a postwar role as a global power—with slavery

In his 2020 book, Colossal Ambitions: Confederate Planning for a Post-Civil War World—a Gilder-Lehrman Lincoln Prize finalist—Arizona State University’s Adrian Brettle takes a detailed look at the world Confederate politicians and planners imagined would exist in the wake of a Southern victory, turning Civil War scholarship on its head with his thesis. Drawing on a rich assortment of speeches, articles, letters, and diaries from the period, Brettle explores the blueprint behind which these planners futilely envisioned—a postwar Confederacy, still based on slavery, that stood not only as an independent nation but also the commercial and equal of the United States.

ACW: In conventional Civil War historiography, Confederate leaders believed that their armies would ultimately win in the field and that life in the South would return to the way it was. Your research, however, revealed a number of surprising presumptions that counter this assessment.

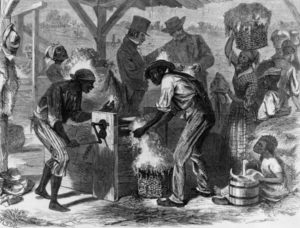

AB: Confederate leaders believed that they were fighting to preserve a slavery-based society and economy. At the same time, though, they portrayed the Republican Party and the Union as something of a throwback, especially in its military aggression, to an old-fashioned European-style tyranny. They insisted that slavery would provide the foundation for a modern, even progressive, nation state pursuing an international agenda of free trade, peaceful collaboration, civilization of less-advanced areas, and exploitation of newly accessible tropical regions.

By Adrian Brettle

University of Virginia Press, 2020, $45

ACW: Modern and progressive? Wasn’t it their belief that the South’s future depended on slavery and unceasing expansion, since a labor system based on coercion was essential to growing staple crops and controlling the African American population?

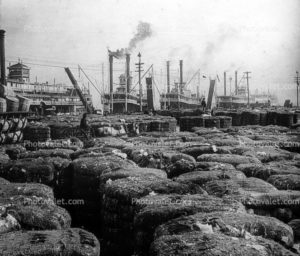

AB: White Southern leaders regarded territorial expansion as necessary for maximum production of staple crops, together with enabling the dispersion and diffusion of the African American population. This is the safety-valve argument—that western or southern expansion would lessen the concentration of enslaved people in a given area in the East, serving as both a social and an economic protection against Black people competing with Whites for wages. Ample cheap land also offered the best chance to non-slaveholding Whites to own enslaved people down the line. It’s based in part on fear of slave insurrections, but also on what I call a giddy excitement that they are on the road to a bright future that is a vanguard for the rest of the world. Preserving slavery and an economy based on agriculture would, Confederates insisted, avert the social revolution they predicted would result from the creation of a White working class in the new factories of Britain and the United State

ACW: In May 1861, Jefferson Davis told the Confederate Congress, “All we ask is to be left alone”—contradicting, it seems, the idea that the Confederacy’s future is progressive.

AB: I call this Davis’ Greta Garbo moment. Left alone but to do what? That is the question I try to answer in the book because Davis went on to describe the ambitions he and his colleagues had for the new nation. He saw the Southern example of White-only egalitarian democracy as an example for Europeans. With mobility increasing and global economic expansion beginning, he saw interracial contact as inevitable and suggested that the racial harmony in which Southerners had such faith would be emulated abroad. The world would follow the Confederate example—a stable society based of a hierarchy of races including Native Americans and Hispanics as well as African Americans.

ACW: What nation would be the most crucial partner in making this system work?

AB: The U.S., not Britain, was to be the Confederacy’s single most important counterpart. Davis was offering the Union a win-win. That’s something historians tend to overlook along with the implicit threat that accompanied it—if you insist on us remaining, we’re only going to harm you. Southerners all read Lincoln’s speeches, and for once they agreed with Lincoln that a house divided cannot stand. They argued that the United States would not thrive if it were half-free, half-slave. The only solution was for the South to be allowed to sustain the North’s industrial revolution as a separate nation and primary trading partner.

ACW: Talk about the traditional view of a Southern agricultural empire and contrast that with the planners’ dream of an industrial, commercial empire, including a navy.

AB: In 1860-61, the talk was all about a borderless world with the Confederacy becoming a global hub of trade and communications. In early 1861, as the Confederacy was being being formed, Charleston business leaders and oceanographer Matthew Maury began talks with officials in Liverpool, England, about establishing a steamship line between those two cities, and even started raising money. By the summer of 1863, the ports of Charleston and Wilmington were crowded with blockade runners. This relative success in keeping trade routes open during the war prompted postwar planners to envision an expanded steamship network linking southern ports with the Caribbean, Brazil, and southern Europe. In addition, leaders saw communications technology as a means of advancing an independent Confederacy, leading to proposals for a Southern undersea cable routed through the Caribbean to Brazil and across the Atlantic to Portugal. A Southern empire in a preimperial age involved new avenues of commerce in a free trade union (that’s why a navy was so important; they needed protection for their merchant fleet). At times, the dream was of being the world’s premier producer of raw materials and consumer of manufactured goods. Plans do change, of course, and at times during the Civil War there is a push for industrialization and economic self-sufficiency, particularly with regard to an arms industry. Some Confederates, especially in the upper and border South, certainly looked forward to an industrialized future as a good thing in itself, but most Confederates recognized that slavery and factories were incompatible. Davis and his secretary of state, Judah Benjamin, preferred to look forward to cornering the world market in commodities, lumber, precious metals, and other mined minerals.

ACW: Didn’t many politicians believe that the states of the Old Northwest, the Southwestern territories of New Mexico and Arizona, and even the Pacific states of California and Oregon were destined to join the Confederacy?

AB: They expected that in the long run California, Oregon, and Washington Territory would become a free trade-oriented independent nation-state—a Pacific Confederacy politically allied with Richmond. More vital was Confederate possession of the New Mexico Territory, as this would be crucial to plans for colonizing Northwestern Mexico, providing access to the port of Guaymas in the state of Sonora. Planners expected Guaymas to be their own San Francisco and terminus of their planned transcontinental railroad. Exiled proslavery Californians might join the Confederate colonizers of these new territories. Meanwhile, planners interpreted the guarded compromise Lincoln put forth during the Secession Winter to permit slavery in the New Mexico Territory as meaning that in any postwar settlement, New Mexico, Arizona, and all 15 slave states would be within the Confederacy.

ACW: Was Northern Mexico going to be annexed as an agricultural territory, colonized for trade, or conquered as a new source of coerced labor?

AB: What Confederates termed the “regeneration” of Mexico would be one of their most urgent postwar priorities. The first step would be to send army veterans out there to push back or bring under control hostile Native American tribes, such as the Apache. Slaveholders accompanied by enslaved people would plant agricultural and mining colonies in Mexico, which eventually would be annexed peacefully, along the Texas model.

ACW: You write that in the final months of the war, the Confederates were obsessed with the thought of making some sort of deal with the United States, even if it meant qualifying some of their independence. What was that about?

AB: Confederate leaders’ biggest delusion was that, no matter how dire the military situation was, they would have a seat at the table in a national postwar reordering. They came up with a number of different proposals that they believed would appeal to Federals, trying first to tempt them with various commercial pacts, and then when these schemes got nowhere, they conceded more and more sovereignty. Some proposals were based on European models like the German customs union that preceded unification; others hearkened back to John C. Calhoun’s scheme for a dual presidency. Finally, in early 1865, Davis and his vice president, Alexander H. Stephens, agreed that if the government of a restored United States was focused on expansion throughout the Western Hemisphere, it might interfere less with slavery at home. The proposal for a joint war to enforce the Monroe Doctrine failed at the Hampton Roads Conference with Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward in February 1865.

ACW: Toward the end of the war, planners were split between those who saw the Northern war aim of emancipation as the central reason why the South needed to fight to the end, and others who saw enlistment of slaves as soldiers—with emancipation as an incentive—as a practical, tactical decision that would be necessary to fill in the ranks. How did proponents of modifying or even abolishing slavery justify this in the South’s social context?

AB: There was a huge debate over the enlistment of African Americans as soldiers in the final months of the war. Lee started it at about the time of Lincoln’s reelection. There was significant discussion in Congress. Georgia’s General Howell Cobb, a former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representative, spoke out stridently against enlisting slaves, saying, “If slaves will make good soldiers, then our whole theory of slavery is wrong”;- in other words, without slavery, what are we? What is overlooked in this stark choice, is that many Confederates expected slavery to change after the war. Amelioration would be necessary to remove abuses and spread ownership more widely. For example part of a Confederate Homestead act which would grant ownership of an enslaved person or family to all army veterans.

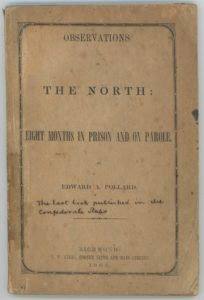

ACW: How did the general “stupefaction” of the Southern populace as it faced surrender of the armies inform the “Lost Cause”?

AB: One of the great champions of the Lost Cause after the war, Edward Pollard, editor of the Richmond Examiner, was captured aboard a blockade runner and held as a prisoner of war briefly in 1864. Back in Richmond, he published a pamphlet in February 1865 in which he argued that the North was so powerful that it would let the South go. The North doesn’t need the South in order to be a great power. That just shows you how much of an invention the Lost Cause is. The “Old South” is a total invention. The argument that the Confederate Army and its generals were heroes compelled to surrender only because of the Union’s superiority in manpower and materiel is a postwar invention. What struck me was the shock and bewilderment among soldiers and politicians that there weren’t going to be an armistice and negotiations—that the Confederate government was not going to have any role in postwar arrangements. They kept waiting for something to happen to make it clear that the fighting had not been in vain. If they weren’t going to have independence, they expected to be welcomed back into the Union as equal partners, with pensions for veterans and compensation for property damage. They thought state debts and Confederate dollars would be honored. They could not conceive of reunion without proof of equality, hence their shock and the need to invent a myth to help them come to terms with this emphatic defeat.

ACW: What do you say to people who question why you write about people who were so terribly deluded?

AB: We don’t know what it was like to live in the 19th century, and we can only read from the existing evidence what they believed. From a 21st century viewpoint it seems obvious that they were deluded. The lesson of history is how, if you like, people can gather evidence to support their point of view. They can build a world, one with a historical basis, that powerfully reinforces their beliefs. It is an important skill for a historian to get to grips with how on Earth people were able to rationalize and then fight for an insupportable vision. When they talked about an independent future, they believed that it would happen. The critical thing to remember is that the planners’ viewpoints were constantly changing due to the war and hence they thought their plans were based in reality of the future they anticipated would come to pass. Their expectations were dynamic, not static, and that independent future looked different depending on when during the war an article is published or a speech is given, when they expected peace to come and in what condition they would be to realize the opportunities that would result.

AB: Lincoln did not blunder. If there is a single takeaway from the book it is the vindication of Lincoln’s opposition to secession and the expansion of slavery. Other than the minority of committed unionist Southerners, most of the leaders—whether secessionist or “cooperationist” (calling for a reformed union)—insisted that unlimited southward expansion of slavery would be the price of any reunion. Furthermore, behind all the “compromises” offered by Confederates during the war to Federals, these leaders also planned to support the further breakup of the Union into both Pacific and Northwest Confederacies. This fragmentation being necessary to secure the Confederacy’s northern border while its planners focused on colossal ambitions elsewhere.

This story contains affiliate links. If you buy a book through this page, we might get a commission. Thanks!