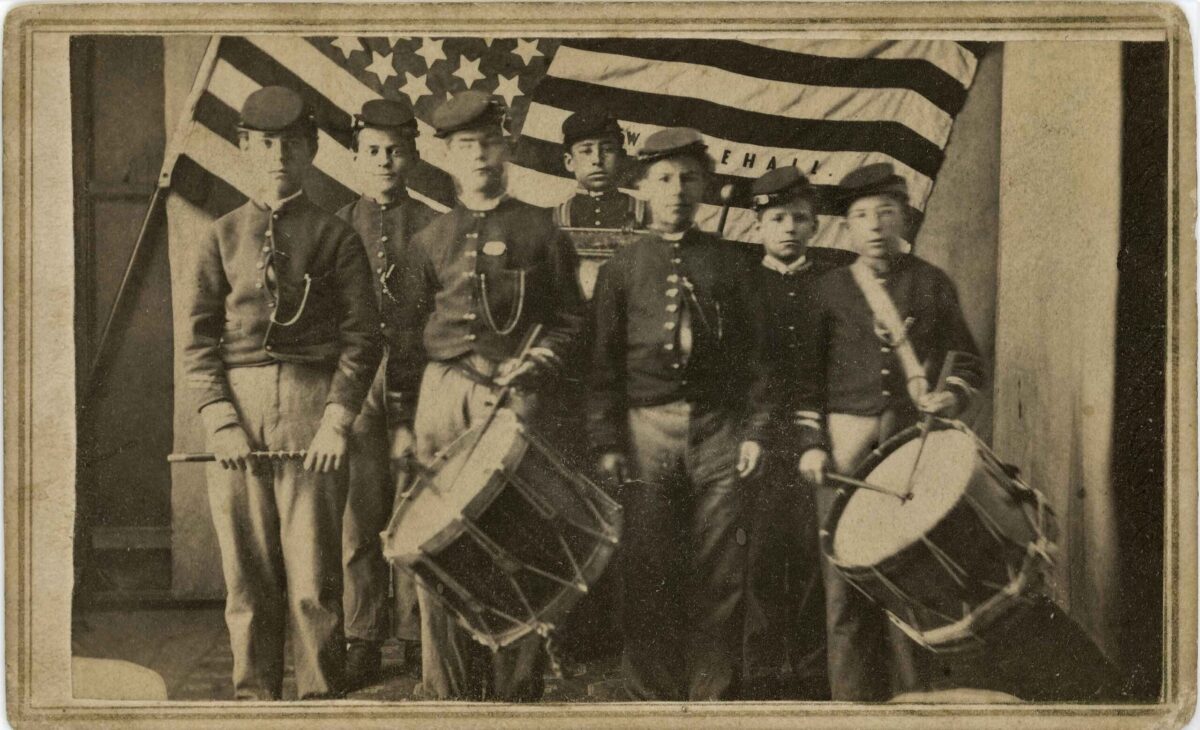

Drumbeats governed Civil War soldiers. Over the din of the battlefield, drum calls were used to transmit commands—the long roll, for instance, was the signal to fall in under arms. In camp, drummers summoned the regiment to meals, to muster, drill, and sick call. When on the march, drummers kept up a lively cadence to boost men’s morale.

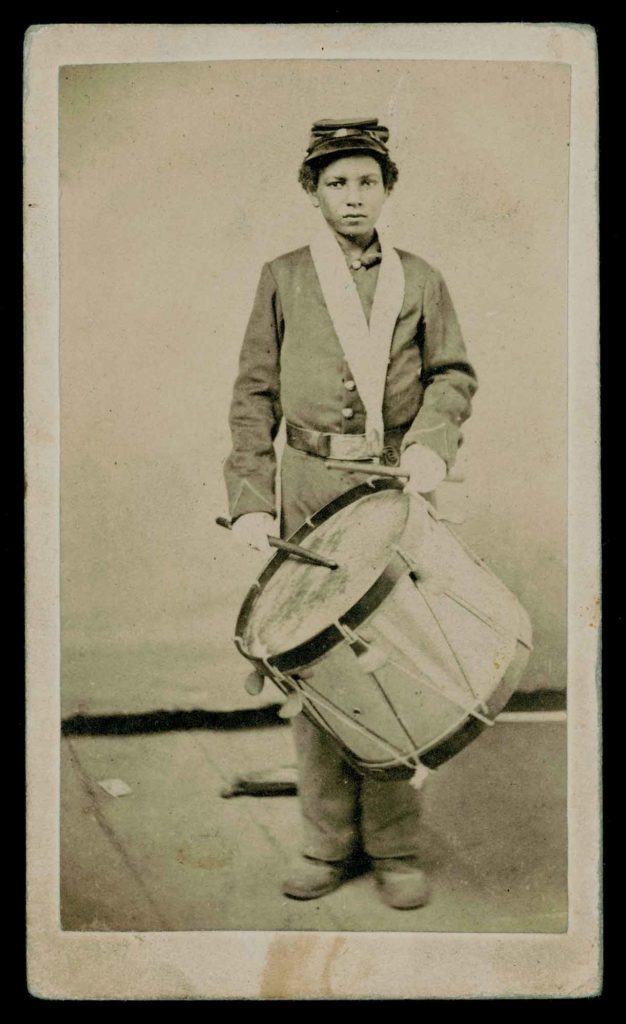

Regular soldiers had to be at least 21, or 18 if they had parental consent to enlist. Noncombatant musicians could enlist at 12. One of the enduring stories of the Civil War is how many boys under 12, swept up in the excitement and yearning for adventure, lied about their age to enlist. It’s unknown how many boys under 12 served in the Civil War, because records reflect fraudulent birth dates.

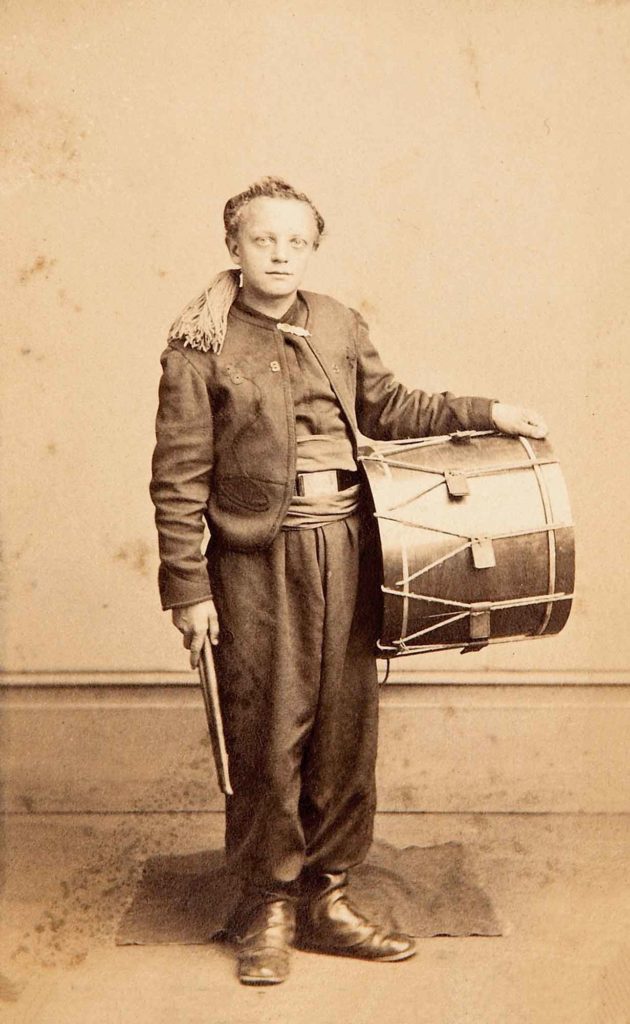

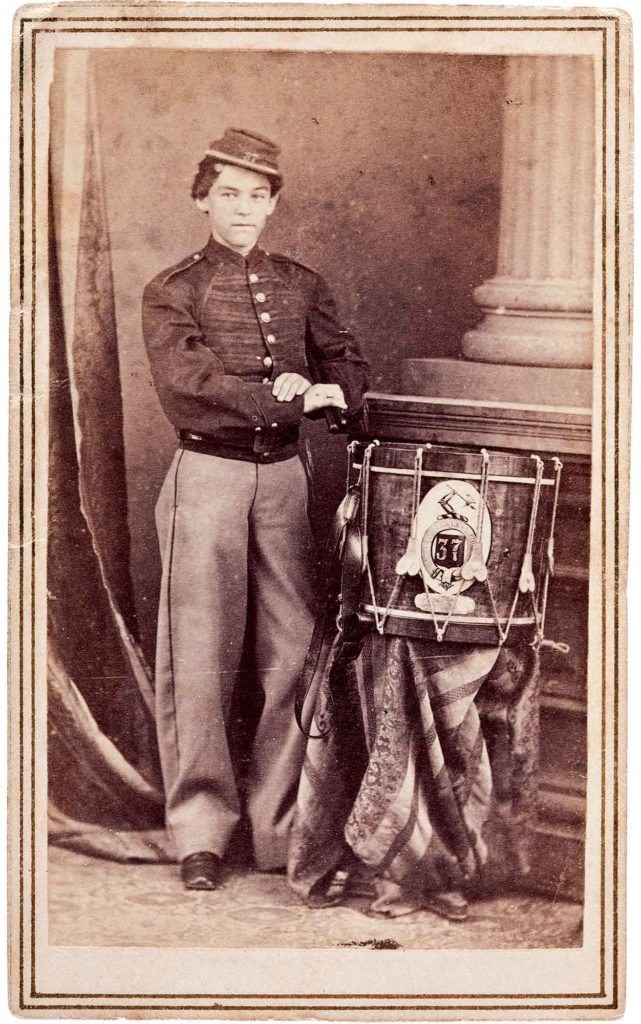

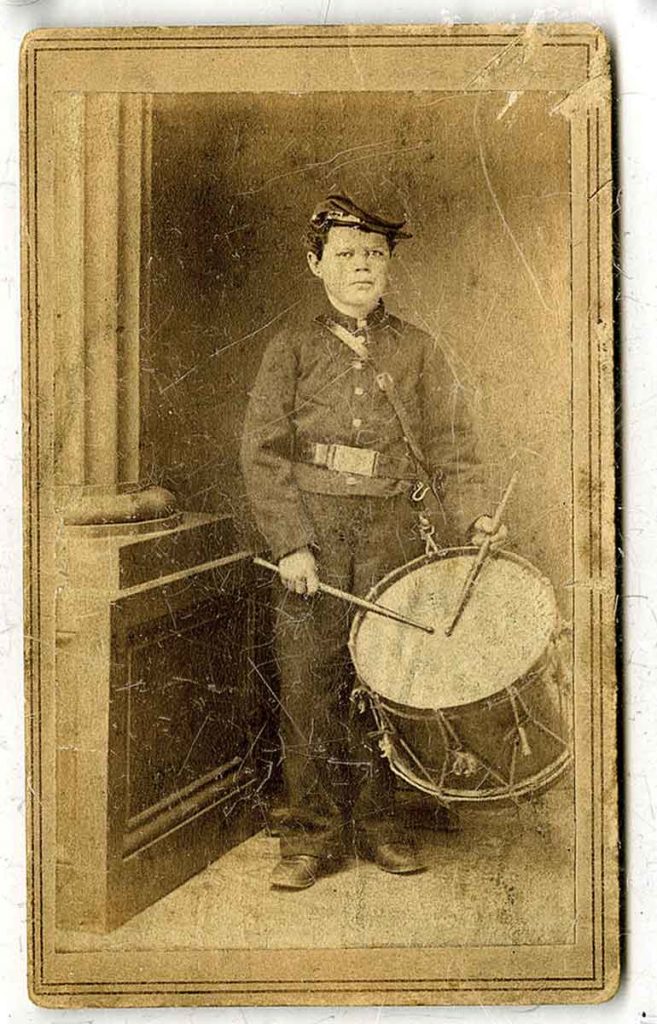

Early in the war, underage boys often tagged along as unpaid “pets” of local regiments. Many turned out to be immature and caused disciplinary problems. The smallest found it exhausting to carry and beat a drum 12 to 14 inches deep and 16 inches in diameter, cut down from the standard of 18 inches deep before the war. Drummers struggled to learn several dozen cadences and variations that went by such colorful names as flams, paradiddles, ruffles, drags, rolls, and ratamacues.

A particular worry for the parents of these boy soldiers was sickness. Underdeveloped immune systems meant thousands of them fell ill and died from endemic camp diseases such as diarrhea and measles.

When the shooting started, noncombatant musicians were supposed to go to the rear to act as stretcher bearers and surgeons’ assistants, often detailed to hold men down during amputations.

Pint-sized volunteers made good newspaper copy. A few drummer boys gained fame fabricating or exaggerating their exploits. Robert Henry Hendershot, for example, enlisted under a false name and gained notoriety when newspapers printed his claims to have participated in the Battle of Fredericksburg and to have captured a Confederate soldier when he was 12. John Clem (or Klem) enlisted in the 22nd Michigan and at age 12 was present at the Battle of Chickamauga in 1863. His unsubstantiated story of shooting a Confederate colonel who ordered him to “surrender, you Yankee (expletive unclear)” and his angelic features made him a celebrity. He retired from the Army as a major general in 1915.

Not all underage heroics were exaggerated. Willie Johnston of the 3rd Vermont was awarded the Medal of Honor at the age of 13. He was the only musician to maintain possession of his instrument during the Union retreat after the Battle of Malvern Hill in 1862.

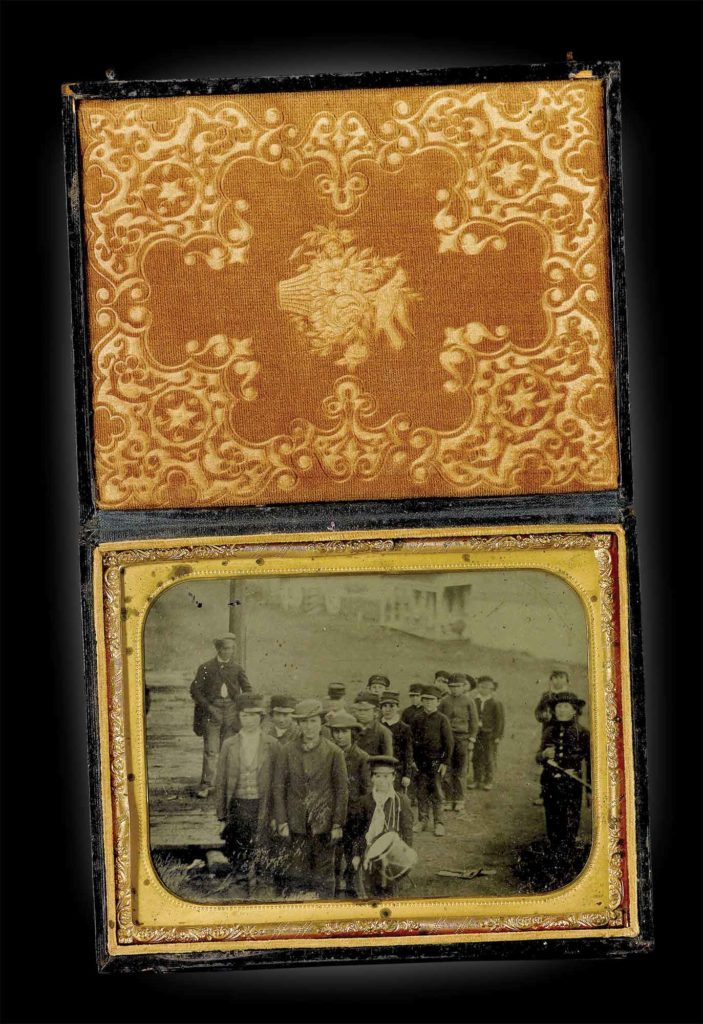

Keeping the Beat: Drummers and other musicians were allowed to enlist at 12, but many lied about their age.