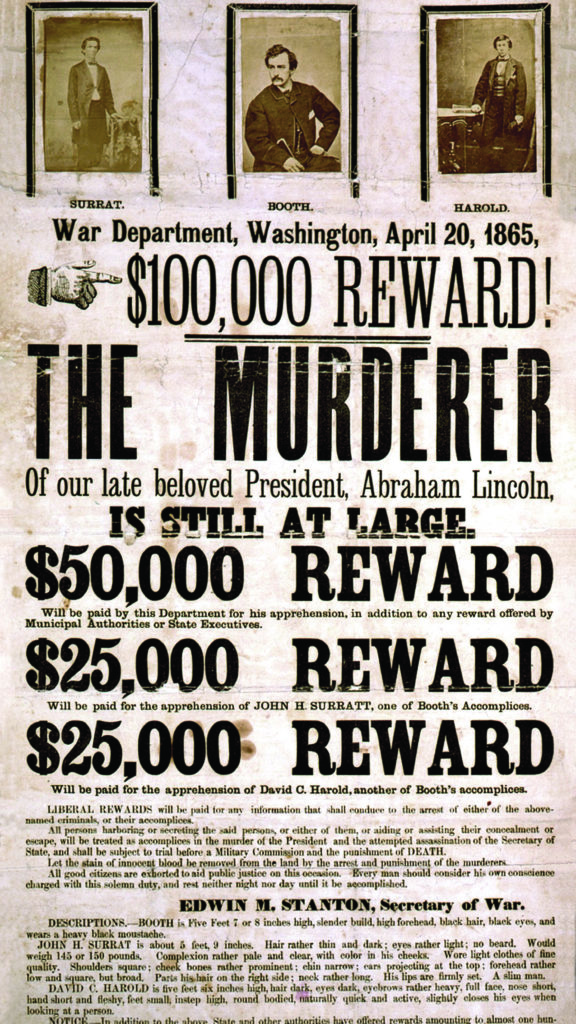

Dozens die when troop transport collides with barge hunting for John Wilkes Booth

It was April 22, 1865—Day 8 of the desperate John Wilkes Booth manhunt across Southern Maryland in the wake of President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination.

Although the war in the Eastern Theater had essentially come to a close, Federal authorities feared that if Lincoln’s notorious killer managed to cross the Potomac River into Virginia, he would undoubtedly get friendlier treatment from the Confederate-leaning locals, making it that much more difficult to bring Booth to justice. All branches of the Union military had been brought into the chase, including vessels of the Potomac Flotilla, which had been so instrumental in keeping Washington, D.C., in Union control over four catastrophic years of war.

As the Civil War progressed, a number of privately owned vessels began working with the flotilla under contract. One was the iron-hulled, propeller-class coal barge Black Diamond, 120 feet long and capable of carrying 200 tons of freight. Built in 1842 by Hogg & Delamater of New York, with a grasshopper-type engine, Black Diamond drew less than six feet of water—ideal for the coal canals that ran between New York and Pennsylvania and also, it proved, the Potomac River.

When Black Diamond received special orders from the Washington, D.C., Quartermaster Depot to join the flotilla on April 22, federal authorities weren’t yet aware that Booth was already in Virginia. Manned by a crew of 11 ardent volunteers, the barge headed from Alexandria, Va., to Piney Point, Md., early that day before steaming back up the Potomac and anchoring near the Blackistone Island Lighthouse at approximately 12:35 a.m. on April 23.

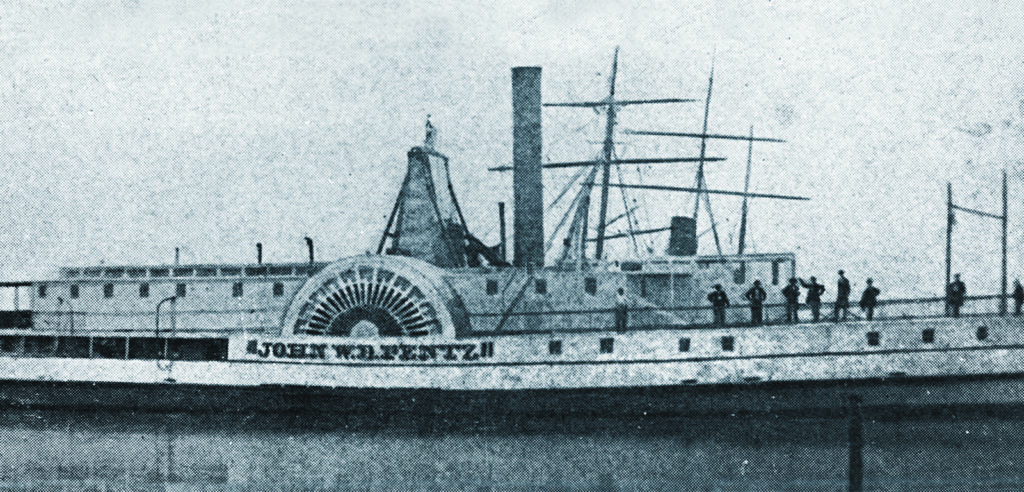

Heading down the river in Black Diamond’s direction on what was initially a clear, moonless night was the 308-ton sidewheel steamer Massachusetts—bound for City Point, Va., and then Fort Monroe. Like Black Diamond, the privately owned Massachusetts (also known as JWD Pentz) was under contract to the federal government. Based in Alexandria and Washington, the steamer was capable of traveling in the Chesapeake Bay, but it was not suited for ocean travel.

Massachusetts had been making regular runs to City Point—Ulysses Grant’s headquarters during the Siege of Petersburg—and Fort Monroe, and was now serving as a troop transport, while Black Diamond had been called upon to help track down Booth.

Carrying a contingent of 300 Federal soldiers recently released from Southern prison camps or convalescent hospitals in the North, Massachusetts left Alexandria about 5 p.m. on the 22nd. The soldiers were to rejoin their regiments to complete their terms of service before being mustered out. At City Point, Massachusetts would secure needed rations before heading on to Fort Monroe. There, the men would offload to an ocean-going vessel that would take them to their new regimental headquarters in New Bern, N.C.

Captain J.M. Holmes of the 3rd Regiment, Veteran Reserve Corps, commanded the Federal troops on the steamer. The Veteran Reserve Corps was among the last units to be mustered out of the Union Army, and its men were now serving as escorts for prisoner exchanges or as officers for troop-transport vessels. Veterans of the 101st Pennsylvania Infantry were part of the group on board, and one later noted that Massachusetts had proceeded downriver “quite nicely” until a strong wind began to blow, causing the river to become rough.

Shortly before 1 a.m., the steamer struck Black Diamond on its port side near the boiler, just aft of the wheelhouse—opening the coal barge’s iron hull down to the waterline. The strong wind and rough waters were likely factors in the accident, but controversy also resulted because Black Diamond was showing only a single light that night. Although that was appropriate according to maritime law in April 1865, it is conceivable that Massachusetts’ captain and pilot, under the conditions, believed they were seeing a shore light as they approached.

Another significant glitch was that Massachusetts was an overloaded, older vessel never meant to carry as many as 300 men. Many were sleeping—quite a few on the open deck, since room in the regular quarters was limited—when they were awakened by a sudden jolt and loud noise.

The collision “staved in,” or crushed, Massachusetts’ bow above the water line. That, wrote William Nott, Co. K, 16th Connecticut, left a hole “large enough to take in five or six men abreast.” The boat’s captain reportedly directed all on board to congregate on the stern in order to raise the damaged bow out of the water. But when Black Diamond unexpectedly swung alongside, hoping to offload its crew onto the less-damaged vessel, the captain (whose name still remains lost to history) became convinced that a rescue boat had arrived. Fearing Massachusetts was about to go under, he ordered his men to jump onto Black Diamond. Some complied and died; some disobeyed and were saved.

In coming alongside, Black Diamond smashed one of Massachusetts’ lifeboats, rendering it unseaworthy and leaving only one boat to assist with the rescue efforts. Despite its bow damage, Massachusetts stayed put, picking up survivors until daybreak. Many of the survivors were forced to remain in the water for three or more hours, clinging to any bit of debris they could find and listening to the cries for help coming from others who had fallen or jumped into the river.

Joseph Husted, Black Diamond’s chief engineer, recalled trying to pull one unfortunate soul from the water with a rope, but “he was so benumbed that he could not catch hold of the line.” Husted did not know whom he was trying to save at the time. Eventually he learned it was George W. Carter, a 16th Connecticut drummer.

Corporal George Hollands, Co. B, 101st Pennsylvania Infantry, recorded being among the first to jump from Massachusetts onto the deck of the other vessel as it swung around, only to realize that he had “jumped out of the frying pan into the fire.” He dashed toward the stern, grabbing a stepladder off the hurricane deck in the process, hoping it would help keep him afloat once he went overboard. Hollands, however, quickly learned “that the river was not deep enough to engulf the masts and all, so [he] threw down the ladder, grabbed one of the guyropes and began climbing up toward the mast.” By doing so, he was saved.

About 150 men reportedly jumped, with approximately half drowning. Those who jumped, in fact, added to the speed at which Black Diamond sank in 3½ fathoms of water: less than three minutes.

Massachusetts managed to travel the 29.3 nautical miles to Point Lookout, Md., the next day. A passing steamer, Marion, had helped in rescuing some of the soldiers from the damaged ship. An initial count of survivors from both vessels indicated that 65 men were missing, but it was eventually determined that 87 had perished.

On April 25, Maj. Gen. Daniel H. Rucker, U.S. chief quartermaster, wrote that he had “directed that a steamer in charge of an officer with a party of men and extra small boats be sent immediately to Blackistone Island [known as St. Clement’s Island today] and vicinity to…recover the bodies of the men lost and bring them to Alexandria.”

One boat sent the following day carried men armed with hooks who were to search for and retrieve as many bodies as possible. Other vessels helped, including Marion and fellow steamers Charleston and James Guy, but the rescue effort was greatly hindered by high waters. In all, 37 bodies were recovered. Most were taken to Point Lookout before being sent on for burial.

It should be no surprise that word of the collision and the heavy cost in lives was quickly eclipsed by the news Booth had been killed by Union trooper Boston Corbett on April 26 while hiding in a barn in rural Port Royal, Va., as well as reports that William Sherman and Joe Johnston had signed a surrender agreement the same day in Durham Station, N.C., ending the war in the East.

In the system in place in 1865, the U.S. Quartermaster Department directly paid the owners of the private vessels chartered for government service. The owners were then responsible for compensating the captains and crew, which eliminated pension and claim rights for these men and their families. The enlisted men working on Black Diamond and the soldiers being transported on Massachusetts were not affected by this policy, however, so their pensions remained intact and some families were able to make successful claims to collect them.

As was standard, the contracts for both ships stated that “war risk” was to be borne by the United States and that “marine risk” was to be borne by the owners. When transporting nothing but government stores and traveling the Potomac, these vessels carried official docu-ments allowing them to pass through the Potomac Flotilla without being searched. In the spring of 1865, there were 612 vessels under contract to the Quartermaster Department.

Since the Black Diamond–Massachusetts calamity fell under the marine risk clause, the U.S. government took no responsibility, placing the entire blame on the owners. But Captain J.G.C. Lee of the Quartermaster Department had no doubt who the main culprits were and wrote to General Rucker on April 25: “From what I can learn the cause of the disaster was extreme carelessness of the pilot or master of the Massachusetts.” In a second letter that day, Lee reported the loss of 66 men, and recommended that both captains and both pilots be arrested and brought to trial. Rucker and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton agreed.

After an inquiry into the incident, the Third Supervising District of Inspectors of Steam Vessels (Baltimore) determined in October 1865 that both pilots “wholly disregarded the rules established for their government, [and] consequently their licenses were revoked.”

Six of the 11 crew members on Black Diamond were initially reported as lost, but that total soon increased to seven. Only four of their bodies were recovered, all civilian employees of the Quartermaster Department at the U.S. Steam Fire House in Alexandria: blacksmiths George W. Huntington, Peter Carroll, and Samuel Gosnell, and carpenter Christopher Farley. All four were from Eastern Pennsylvania and had purportedly volunteered to join the crew for this patrol.

Among Black Diamond’s survivors was Joseph Husted, who attempted to claim a pension in August 1890 but was turned down by the Quartermaster Department, as were the other civilian employees. The enlisted soldiers aboard Massachusetts at the time of the collision, though, were eligible for pensions, and many of their families were successful in collecting those after the war.

It is difficult to compile a complete list of the names of the men lost on Massachusetts, as they represented several regiments. Most were recently exchanged prisoners of war, captured at Plymouth, N.C., on April 20, 1864, and sent to the Confederates’ infamous Camp Sumter prison camp in Andersonville, Ga. After being transferred from Andersonville to the Confederate prison camp in Florence, S.C., in December 1864, the men were eventually exchanged and nursed back to health by Union doctors at Camp Parole near Annapolis, Md. All were returning to their various regiments to complete their terms of service.

Thirteen members of the 16th Connecticut were on board Massachusetts, and seven were among those who reportedly drowned: Sergeant Samuel E. Grosvenor; Corporal William T. Loomis; Privates Charles L. Robinson, Henry S. Loomis, George N. Champlin, and Edward Smith; and, as noted, Company D drummer George W. Carter. Only Robinson’s body was recovered.

Of the 87 men to perish, the names of only 26 are known. Some had their bodies recovered and sent home for proper burial, but some unfortunately still rest on the bottom of the Potomac River.

Black Diamond was never raised either. Its smokestack and upper pilot house remained visible above water for many years, but it was determined that the damage was too great to attempt a recovery. As speculated in the May 1 edition of the Washington Evening Star: “She will doubtless be a total loss, as she is an old vessel, and would not hold together if attempts were made to raise her.”

In 1867, Veder Fox of Elizabethport, N.J., requested permission to raise a number of vessels in exchange for a percentage of the proceeds gained from selling any iron recovered. It is not known if he was successful in raising any of the wrecks, including the doomed Black Diamond, which in all probability remains at the site of its fateful encounter with Massachusetts 155 years ago.

Karen Stone is the Museum Division Manager for St. Mary’s County, Md., where this event took place. She completed her undergraduate work at Gettysburg College, and obtained her master’s degree at Penn State University. Stone lives with her husband in Fredericksburg, Va.

_____

‘He bade us goodbye’

Amid the pandemonium, George W. Carter of the 16th Connecti-cut Infantry followed the lead of many of his fellow soldiers and leapt from the damaged steamer Massachusetts onto the deck of Black Diamond. The 20-year-old Company D drummer quickly realized, however, that Black Diamond had begun to sink. He jumped into the churning water and grabbed hold of a wooden plank. For more than an hour, he toiled to stay afloat, hoping for a miracle. But about 2 a.m., the struggle ended. As Corporal George Hollands of the 101st Pennsylvania Infantry recalled:

“(Carter) grasped hold of the keel of the boat, or something else, and was hanging on for dear life and calling for help. One of the crew up in the rigging got hold of a rope and time and time again threw it to where the boy was, telling him to grab for it. The boy couldn’t get hold of it. Every now and then a wave would wash over him and strangle him, and as he would emerge from it he would call for the rope. He finally became exhausted and cried out to us that he could hold out no longer….He said he was a drummer of Co. D, 16th Conn., and asked us to inform his mother that he was drowned. He bade us goodby[e], and as the next wave washed over him he loosened his hold and sank beneath the waves.”

“(Carter) grasped hold of the keel of the boat, or something else, and was hanging on for dear life and calling for help. One of the crew up in the rigging got hold of a rope and time and time again threw it to where the boy was, telling him to grab for it. The boy couldn’t get hold of it. Every now and then a wave would wash over him and strangle him, and as he would emerge from it he would call for the rope. He finally became exhausted and cried out to us that he could hold out no longer….He said he was a drummer of Co. D, 16th Conn., and asked us to inform his mother that he was drowned. He bade us goodby[e], and as the next wave washed over him he loosened his hold and sank beneath the waves.”

Carter hailed from the town of Suffield, near Connecticut’s northern border with Massachusetts. His body was never recovered, the same fate as five others from his regiment who had perished following the Massachusetts–Black Diamond collision that morning. –C.K.H.