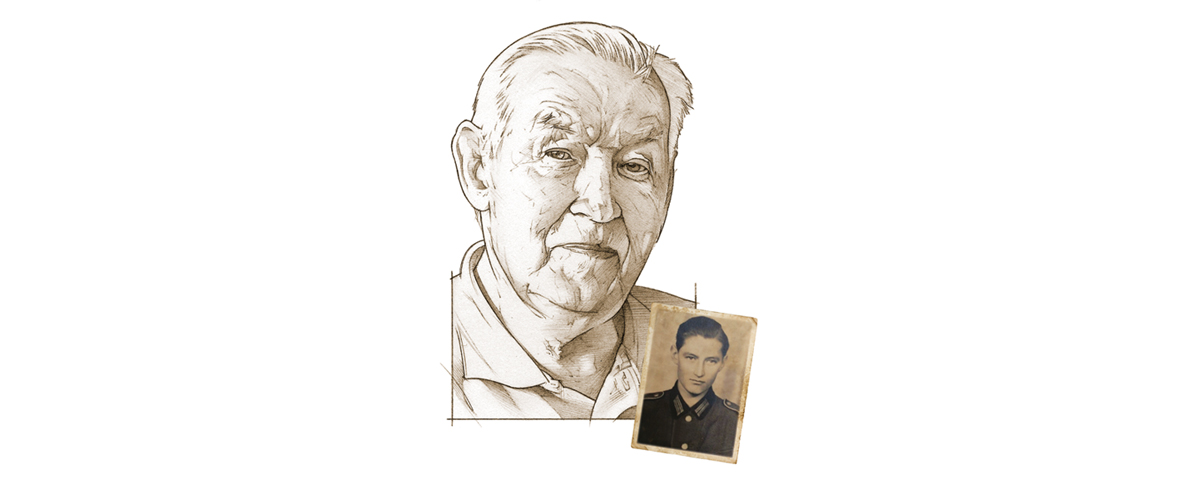

Paul Golz was born in Pomerania, near the Baltic Sea, on April 4, 1925, and was just 17 years old when he joined the Wehrmacht in the fall of 1943. He was on guard duty on France’s Normandy coast in the early morning hours of June 6, 1944, tasked with scanning the skies for enemy planes. That morning he saw scores of them and within days was a prisoner of the Allies. Golz spent the rest of the war in a POW camp in Virginia. In 1948 he returned home and joined the West German Federal Border Guard. Ten years later he entered his country’s diplomatic service, retiring in 1990. The 92-year-old resides in the summer resort town of Königswinter, Germany. Last June he met with journalist Liesl Bradner near Utah Beach and spoke about his wartime experiences.

What prompted you to enter the Wehrmacht?

My father had served in World War I and had experienced bad things. He told me never to shoot a human being who is not threatening me or not carrying a weapon. I turned down registration in the Waffen-SS and instead joined the Wehrmacht. In December 1943, after completing training, I came down with a severe case of diphtheria and scarlet fever. I was lucky, because my sickness saved me from being sent to the Eastern Front with my unit.

What happened when you returned to duty?

I was assigned to a machine gun team in Grenadier Regiment 1057 of the 91st Air Infantry Division. Our first move was to Saint-Nazaire, France. When information got out the Allies were not in Saint-Nazaire, we got orders to head to Normandy, and around mid-May we dug in near the Cherbourg heights. For the next few weeks we planted “Rommel asparagus”—sharpened logs connected with barbed wire meant to obstruct landing areas for Allied gliders and paratroops.

When did you realize the invasion had begun?

Around 3 a.m. on June 6 near the town of Caen I spotted “Christmas trees” [flares] dropped by the Allies to mark a paratroop landing area. They were nice to look at, but then I saw so many parachutists coming down, I knew it was an invasion.

What happened then?

I hadn’t had any food or water for three days, so around 6 a.m. I walked to a village and begged for milk. The French there knew me, but this time they said, “Go away! The Allies already landed with tanks.” I went back to my unit and we marched toward Sainte-Mère-Église, which was two or three hours away. We didn’t make it there, though, as we were told to change our direction toward Carentan.

We stopped in the fields where gliders and parachute troops had landed. I was so hungry. I hoped to find something edible in the pastures, which were separated by thorny hedges and ditches. Suddenly, I saw something moving in the hedges. When I approached, I saw that it was a parachutist whose face was covered with camouflage paint. I cocked my gun and walked toward him. He was trembling with fright. Since I didn’t speak English, I said, “Ich tu dir nichts” (“I won’t do anything to you”). Because of my calm tone, he offered me his canteen. I was thirsty, but I made him drink first. His rifle had been thrown away, but I took away the knife he wore on his leg and took him to the prisoner holding area.

The next day I saw my first dead man, a paratrooper. When my comrade began rummaging through the dead man’s uniform, I told him not to take anything that wasn’t his. Ignoring me, he searched the man and found a wallet with a picture of a woman in it. He pocketed it and then tried to take a gold signet ring from the dead man’s finger. He couldn’t get the ring off, so he decided to cut the entire finger off with his bayonet. I told him not to do it, and that if the Americans found the finger, they would kill him.

An American tank stopped at the entrance to the pasture where we hiding. A soldier came and shouted, ‘Come on boys, hands up!’

When were you taken prisoner?

From June 6 to 9 Americans were fighting to capture a bridge on the La Fière causeway. German troops had taken up defensive positions at the end of the 500-yard causeway, the only means of crossing a floodplain beyond the swollen Merderet River.

After firing my machine gun at a column of American trucks, my comrades and I retreated. An American tank stopped at the entrance to the pasture where we hiding. A soldier came and shouted, “Come on boys, hands up!” The Americans were nice—I didn’t think they would shoot me.

We were taken to a prisoner collection point and searched. They found the American woman’s photo on my comrade, and a guard struck him on the back with the butt of his rifle. “That’s what you get!” I said to my friend. “If they’d found the dead soldier’s ring on you, they would’ve killed you.” We were then marched to Utah Beach.

What was your first thought when you saw the beach?

As soon as we walked over the dunes and saw thousands of ships and all those landing boats and barrage balloons, I knew the war was lost.

Where were you taken?

We waded out to a landing craft that took us to a British transport ship. I had my first meal in three days on that ship, and I can remember it clearly. It was frankfurter sausage, mashed potatoes, white bread and a cup of coffee.

We sailed to England, then took a train to Scotland, where we spent two weeks in a camp. Then we boarded the ocean liner Queen Mary. After about five days we reached New York, where they put us on a train to Camp Patrick Henry in [Newport News] Virginia.

How were you treated?

I liked it very much. I had my first Coca-Cola in the camp canteen. As prisoners we served the Americans their food, but we also ate the same things they did. Once a month we were allowed to write a letter to a German family. The German authorities blacked out the parts we wrote about having chocolate. I remember having clean white bed sheets and listening to Mickey Mouse and Red Skelton on the radio.

How long were you imprisoned?

Until May 1946, when the United States released all prisoners of war. We were told we were going home, but instead we were sent to Stuckenduff Camp in Scotland to rebuild the roads. We refused at first, but it didn’t change anything.

In Scotland we were allowed to move around freely and get paying jobs. I worked as a gardener in the city after 5 p.m. In the winter they had us clear the snow from the [soccer] fields. We must have pleased the coach, because he invited me and a colleague to his house on Sundays. Meat was still being rationed, but they shared some with us.

The coach told me Pomerania had been annexed by Poland and that I should stay in Scotland and work in agriculture. I told them I wanted to return to Germany and find my family. There was no sign of them when I went back in October 1947. I first lived with my uncle in Hamburg, from there I went to the Rhineland and stayed with my brother.

Why do you think you were able to survive the war?

I think I had a guardian angel on my shoulder. I had only one small piece of shrapnel tear a hole in my uniform after I was captured, and I never had to fight in Russia. For that I am very thankful. MH