After gaining a foothold in Italy, Allied commanders needed to keep the Germans guessing about their plans in the Mediterranean. General George C. Marshall wrote to Eisenhower on October 21, 1943: “It seems evident to us that Patton’s movements are of great importance to German reactions and therefore should be carefully considered. I had thought and spoke to [Eisenhower’s chief of staff, Walter Bedell] Smith about Patton being given a trip to Cairo and Cyprus but the Corsican visit appeals to me as carrying much more of a threat [to northern Italy].” Eisenhower replied, “As it is I am quite sure that we must do everything possible to keep [the Germans] confused and the point you have suggested concerning Patton’s movements appeals to me as having a great deal of merit. This possibility had not previously occurred to me.” For all Marshall’s apparent certainty, however, he was making an assumption, albeit a logical one: besides Patton, the United States had no other seasoned and widely known general other than Eisenhower. But it was an assumption nonetheless, made without any evidence of German opinion.

After gaining a foothold in Italy, Allied commanders needed to keep the Germans guessing about their plans in the Mediterranean. General George C. Marshall wrote to Eisenhower on October 21, 1943: “It seems evident to us that Patton’s movements are of great importance to German reactions and therefore should be carefully considered. I had thought and spoke to [Eisenhower’s chief of staff, Walter Bedell] Smith about Patton being given a trip to Cairo and Cyprus but the Corsican visit appeals to me as carrying much more of a threat [to northern Italy].” Eisenhower replied, “As it is I am quite sure that we must do everything possible to keep [the Germans] confused and the point you have suggested concerning Patton’s movements appeals to me as having a great deal of merit. This possibility had not previously occurred to me.” For all Marshall’s apparent certainty, however, he was making an assumption, albeit a logical one: besides Patton, the United States had no other seasoned and widely known general other than Eisenhower. But it was an assumption nonetheless, made without any evidence of German opinion.

As a result, Patton made a series of highly visible appearances, beginning with Corsica on October 28 and followed by Malta and Cairo. There is no evidence in German intelligence records that the enemy paid any attention to Patton’s movements. Instead they were focused on Allied shipping and ground force capabilities. In February 1944, as planning for D-Day was in full swing, the Allies began an elaborate deception operation, codenamed Fortitude. To give the Normandy landings the best possible chance at success, the Allies wanted the Germans to believe that the main invasion in France would take place at Pas de Calais in July, and that Normandy was a feint to draw German forces south. The fictitious First U.S. Army Group (FUSAG) would conduct the equally fictitious landings; Eisenhower appointed Patton, who had arrived in London on January 26, as the faux commander.

Thanks to false information fed through double agents, by March 23 the Germans began associating Patton with FUSAG. But they had not yet conclusively identified him—or anyone else—as the commanding general. On April 1, Germany’s Foreign Armies West noted, “It seems possible that [Patton] has taken command of the First or Ninth Army in England.”

Despite the Allies’ best efforts, the Germans did not decide until mid-May—months after they concluded that the Allied invasion would land at Pas de Calais or in Belgium—that Patton had indeed taken command of FUSAG. However, his leadership of the supposed landings at Pas de Calais appears to have been incidental to the strategic conclusions the Germans reached regarding the Allied invasion. None of the surviving pre-invasion records from the command of Army Group B, responsible for defending northwestern France, mention Patton outside the FUSAG order of battle. In contrast, the Germans methodically recorded the statements and meetings of Montgomery and Eisenhower, and bombarded their agents with questions about Montgomery’s movements.

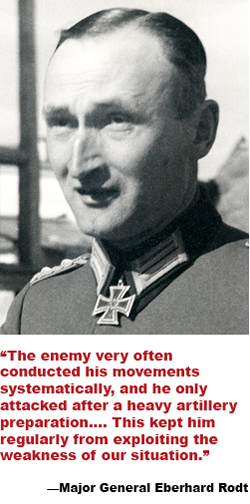

This attention was not misplaced: Montgomery led the Allied ground forces in the invasion, while Patton was relegated to the sidelines until he was placed in command of Third Army nearly a month after D-Day. Montgomery would show himself to be methodical and cautious in his advance, which the Germans had observed of him in North Africa. But in the weeks to come, Patton’s agility and boldness would finally demand attention from some of Germany’s finest commanders.