During the broadcast of Super Bowl LIV in 2020 a three-minute commercial featured a boy with a football dashing past several current and former National Football League stars who encouragingly yell, “Take it to the house, kid!” amid cheerful music. In the middle of the ad the boy pauses, as does the music, and he gazes up at the statue of Arizona Cardinals safety Pat Tillman outside State Farm Stadium in Glendale. After the ad aired, a familiar debate bubbled up in the press and on social media. Was the NFL honoring or exploiting the memory of a generation’s most famous fallen soldier?

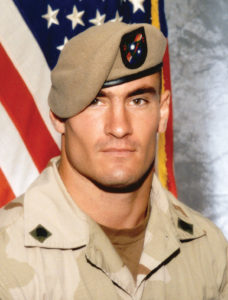

After Tillman walked away from football to join the Army in 2002, he refused to speak publicly about it, believing his enlistment spoke for itself. But circumstances took his life, and therefore his legacy, in directions he couldn’t have foreseen, from the invasion of Iraq to his preventable death in Afghanistan in 2004.

The events surrounding his final moments were initially obscured behind a smoke screen of medals, political praise and redacted documents before the truth came out he’d been killed by members of his own platoon. Even today, after a slew of investigations and a congressional hearing, his story evokes bitter disagreement about who was to blame and what his service meant.

In an interview given five years after Pat’s death his mother, Mary “Dannie” Tillman, bemoaned her son’s iconic status. “He was a human being, and by putting this kind of heroic, saintly quality to him, you’re taking away the struggle of being a human being,” she said. “He had to make choices, just like we all do.”

Why had Tillman chosen the Army over the NFL? What had he sought to accomplish as an enlisted soldier? A few clues—including football-related interviews, his family’s remembrances and passages from his personal wartime journal—bring us as close as we may ever get to answering such questions.

Patrick Daniel Tillman Jr. was born on Nov. 6, 1976, and raised with two younger brothers in suburban Fremont, Calif., on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay. An all-around gifted athlete, he became a football star on both offense and defense, making up for his relatively slight stature with dedication in the weight room, a taste for delivering hard hits and the acumen to guess an opponent’s moves and react quickly. By age 16 he stood 5 feet 11 inches and weighed 195 pounds. His aggressive nature got him in trouble during his senior year when he assaulted another teen in a parking lot brawl and landed in juvenile hall for 30 days. Fortunately, the misdemeanor did not prevent him from claiming Arizona State University’s last football scholarship for the 1994 season. He joined the team as a defensive specialist.

Tillman said his short time in lockup prompted a major reassessment of his priorities, and in college his ambition kicked into high gear. He’d built a reputation among friends for climbing tall objects and taking death-defying leaps from canyon ledges into trees. At ASU he applied his energies to voracious reading and debates on politics and international relations. He earned his bachelor’s degree in three and a half years, graduating in December 1997 with a 3.84 grade point average.

The young athlete became a darling of the press for his mix of eccentric and admirable qualities, including a patriotic streak. In one interview Tillman mentioned legendary World War II Gen. George Patton. “He made some comment one time,” Pat said, “something to the effect of, ‘No one ever won a war dying for their country. Let the other son of a bitch die for his.’ It’s things like that, you know, it’s guys like that, guys where their attitude—they’re a little bit crazy—but it’s that craziness that propels them to greatness.”

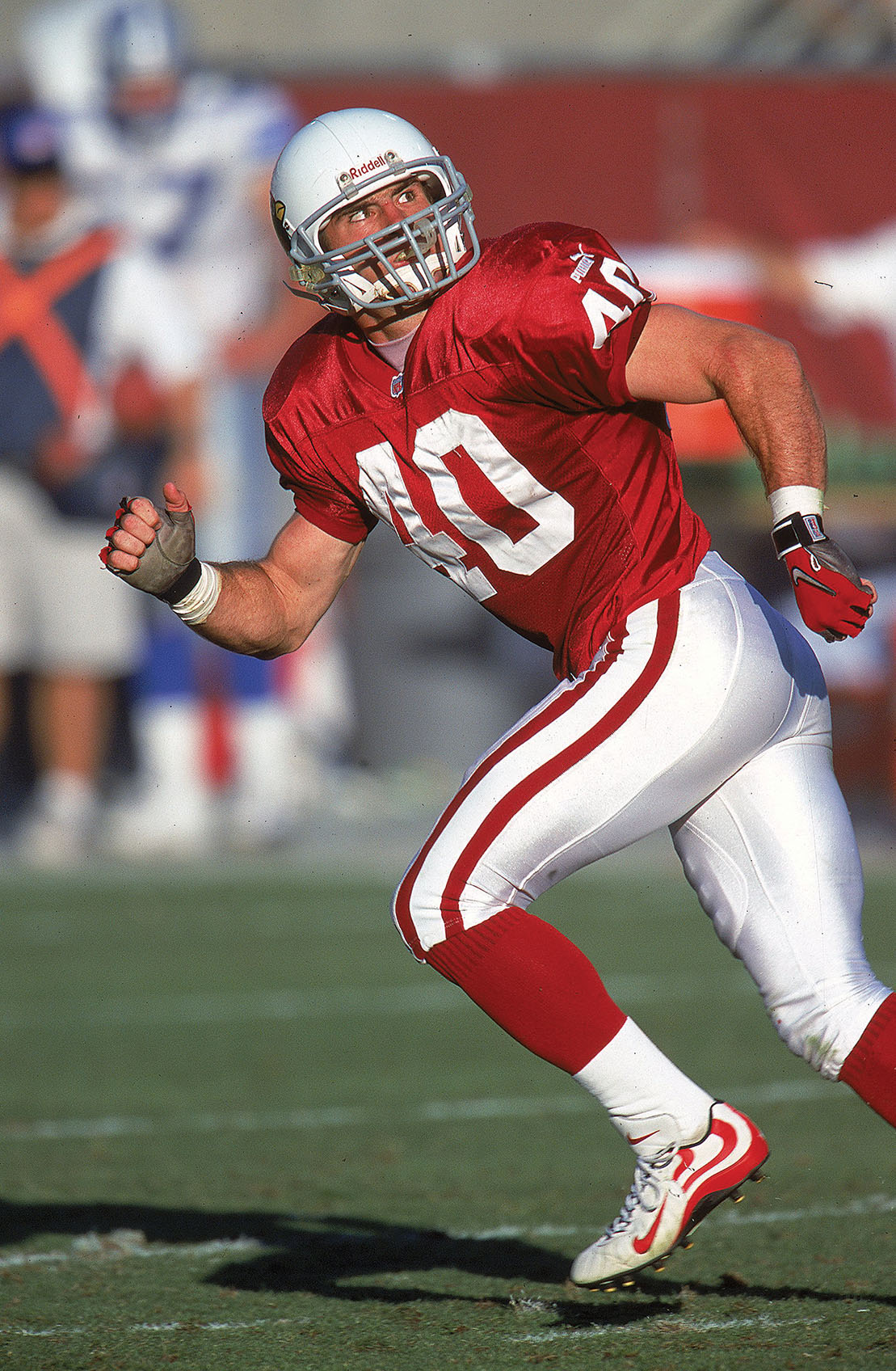

Still considered undersized and somewhat slow on his feet for pro football, he nevertheless made it onto the NFL’s radar by leading his college team in tackles. Of the 241 players chosen in the 1998 NFL draft, Tillman came up number 226. He signed a one-year contract with the Cardinals for $158,000, the league minimum. As he had done throughout his youth, he outworked and outhit teammates to earn his spot as the team’s go-to strong safety, though he never earned more than the league minimum salary, which for a fourth-year player was $512,000.

Meanwhile, he maintained his reputation for unconventional antics. He initially rode his bicycle to team practice, eventually upgrading to a secondhand Volvo station wagon. During the off-season he finished a marathon, the only NFL player to do so in the year 2000. In 2001 he completed an Ironman half-triathlon, comprising a 1.2-mile swim, a 56-mile bike ride and a 13.11 mile run. He also re-enrolled at ASU to pursue a master’s degree in history.

Tillman twice turned down a major payday—first a $9.6 million offer in 2001 because he didn’t want to leave Arizona to play for the St. Louis Rams, and then a $3.6 million offer from the Cardinals in spring 2002.

The Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on American soil hit Tillman hard. He watched TV footage of the unfolding tragedy all morning from home and then with teammates at the Cardinals’ practice facility. He was especially shocked to see footage of desperate people holding hands and leaping from the blazing World Trade Center towers.

With pro sports on hold, he sat for an on-camera interview the next day. “My great grandfather was at Pearl Harbor, and a lot of my family…has gone and fought in wars, and I really haven’t done a damn thing as far as laying myself on the line like that,” he said. “So I have a great deal of respect for those that have.” The interviewer then asked whether he was itching to return to the field. “We play football, you know?” he replied. “It is so unimportant compared to everything that’s taken place.”

While Tillman’s parents encouraged their boys to question authority, they also taught reverence for fellow Americans who had answered the call to serve. After Pat’s death, Dannie—herself a college history major—reflected on those lessons. “Discussions about the military had been part of the boys’ childhood—why people fight for their country; why they should; when it is right to do so; the effect of war on people; how it crushes them tragically or enables them to do heroic things,” she wrote. Dannie recalled some of her own favorite memories, including visits to Gettysburg National Military Park and watching plebes march at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

In the six months following 9/11 Pat explored his options, and in February 2002 he ventured to Provo, Utah, to climb frozen waterfalls and speak with a former Force Recon Marine. After deciding to join the Army, Tillman told middle brother Kevin, then a minor league baseball player with the Cleveland Indians organization. To no one’s surprise, Kevin, who had considered military service since he was a teen, quit baseball to join up with Pat. The Tillmans met with a recruiter who explained that if they joined the Army Rangers, the brothers would incur a modest three-year commitment, do short (three-month) deployments and could choose to be based at Fort Lewis, Wash., just south of Seattle.

Pat and Kevin—just 14 months apart and lifelong best friends—called Dannie on Mother’s Day 2002 to explain their plan. They had wanted to so do in person, they said, but someone at the recruiting station had recognized Pat, and the brothers thought they might soon be in the news. Although both had college degrees, they chose not to become officers, loathing the idea of having to send others into harm’s way.

On April 8, 2002, Pat penned a reflective document he titled “Decision,” writing in part, “It seems that more often than not we know the right decision long before it’s actually made.” Being an NFL player, he noted, “strokes my vanity enough to fool me into thinking it’s important…[but] especially after recent events I’ve come to appreciate just how shallow and insignificant my role is.” The next month Pat married Marie Ugenti, his one and only girlfriend, and the newlyweds honeymooned in Bora-Bora. In June he and Kevin signed their enlistment papers and took the oath.

From the moment the Tillman brothers joined up, the nation’s military leaders were watching. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld wrote a memo to the Army secretary calling Tillman “world-class” and adding, “We might want to keep an eye on him.”

On June 28 he wrote Pat a personal letter of praise. Rumsfeld’s senior military assistant later said it was the only time he could recall the defense secretary having sent personal congratulations to a soldier on his enlistment. Major General John Vines also sent a letter, inviting the Tillmans to join the 82nd Airborne Division instead of the Rangers.

On July 8 Pat and Kevin traveled to Fort Benning, Ga., for basic and advanced individual training. Aged 25 and 24, respectively, they were dismayed at the immature behavior displayed by many of their younger fellow recruits, many of whom had joined for practical instead of patriotic reasons. Pat journaled his alarm at seeing “all these guns in the hands of children.” He also wrote of longing for the wife and career he’d left, along with the hope his military experience would “free up my conscience to enjoy what I have.”

The Tillman brothers stuck it out through airborne school and the Ranger Indoctrination Program, and just before Christmas 2002 they were sent to Fort Lewis as the newest members of 2nd Platoon, Company A, 2nd Ranger Battalion.

By early March 2003 Pat and Kevin were setting up tents and stringing concertina wire with the rest of Company A near Arar, Saudi Arabia, within 40 miles of the Iraqi border. Wearing uncomfortable protective suits in the desert heat to protect them from Saddam Hussein’s rumored chemical and biological weapons, they followed news of the invasion, Operation Iraqi Freedom, which began on March 20.

On March 27 Rangers finally boarded helicopters to join the fight—but the Tillmans remained in camp. With no seniority or experience, they were seen as more liability than asset. “I’m not out for blood or in any hurry to kill people,” Pat wrote in a fiery journal entry, “however, I did not throw my life to s___ in order to fill sandbags and guard Hummers. This is a f______ insult that boils my blood. All I want to do is rip out the throat of one of these loudmouth f___s who’s going as opposed to me.” Although he expressed great misgivings about the war in Iraq, suggesting it was about oil and little else, Pat clearly wanted to taste combat.

As it happened, while assaulting Qadisiyah Air Base northwest of Ramadi on that first mission, Manuel Avila, the M249 squad automatic weapon (SAW) gunner in Pat’s four-man fire team, was shot twice in the chest. Avila survived, but from that point Pat took his spot on the SAW.

The closest the Tillman brothers came to major action in Iraq was the high-profile rescue of Pfc. Jessica Lynch, a 19-year-old supply clerk in the 507th Maintenance Company who was captured by the enemy on March 23 after the convoy she was traveling in took successive wrong turns into the southern city of Nasiriyah, inadvertently becoming the tip of the invasion spear.

Breathless initial news reports claimed Lynch had fought until her M16 ran out of ammunition, sustained stab and gunshot wounds, and was tortured—none of which turned out to be true. In fact, she hadn’t fired a shot, and the injuries she received occurred when the Humvee she was riding in collided with a tractor trailer during the ambush. Her name was eventually linked to Pat’s in the official record, as each became characters in a mendacious wartime propaganda campaign.

Lynch’s rescue—a massive undertaking involving roughly 1,000 troops—came at midnight on April 1. The special operations team responsible met light resistance and suffered zero casualties as they bore Lynch on a stretcher from Saddam Hussein Hospital. A camera crew from the 4th Psychological Operations Group recorded the action, during which someone placed a conspicuous U.S. flag on Lynch’s chest. The Tillman brothers, part of a standby quick-reaction force, spent a cold night waiting at bombed-out Tallil Air Base.

Beginning on April 9 Pat and Kevin spent five weeks patrolling out of an aircraft hangar at Baghdad International Airport. Pat fired his weapon just once, on April 21, to ward off approaching vehicles with warning shots. In mid-May the Tillmans, having yet to earn the coveted Combat Infantryman Badge, returned stateside to attend Ranger School at Fort Benning. On November 28, after nine arduous weeks, the brothers received their shoulder patches—or tabs—marking them full-fledged Rangers.

As 2003 drew to a close, Pat learned that since he had deployed to a war zone, he could be honorably discharged under special circumstances. His agent told him several NFL teams were hoping to sign him to play in the fall 2004 season, but Pat refused to consider an early discharge. He would stick to his three-year commitment.

Pat, Kevin and the rest of 2nd Platoon (the “Black Sheep”) arrived in Afghanistan for their second deployment on April 8, 2004. Six days later they helicoptered to Forward Operating Base Salerno, along the Pakistani border in the southeastern province of Khost, to search nearby villages for Taliban activity.

On April 22, just two weeks into the deployment, Pat was killed. A day later superiors submitted a Silver Star recommendation that claimed Tillman had “put himself in the line of devastating enemy fire” during an ambush. The recommendation quickly went up the chain of command, along with a posthumous promotion to corporal. News accounts parroted the official line Pat had succumbed to enemy fire while saving fellow Rangers. Within weeks, however, that version of events began unraveling.

In fact, on the afternoon of Pat’s death headquarters had ordered Black Sheep commander 1st Lt. David Uthlaut to split his platoon to meet a predetermined time line. As they threaded through steep-walled valleys in their Humvees and Toyota Hilux pickups, the platoon’s two sections lost radio contact with each other. The trailing section, whose members included Kevin Tillman, soon came under ambush by mortars and small arms from the hills above.

As members of the other section, including Pat, dismounted from their vehicles and rushed to help, trigger-happy Rangers—many in their first firefight—mistook Pat and fellow rescuers for enemy combatants. They killed Sayed Farhad, an Afghan ally. Standing beside Farhad, Pat took an initial 5.56-caliber round to the chest, then three more to the right forehead, likely from a SAW. According to fellow Ranger Pfc. Bryan O’Neal, as he and his teammates came under fire, Pat waved his arms over his head, yelling, “I’m Pat Tillman! I’m Pat f______ Tillman! Why are you shooting at me?!” Wounded in the friendly fire incident were Lieutenant Uthlaut and Spc. Jade Lane.

Kevin arrived on scene 10 minutes after the shooting. He was told his brother was dead but not about the circumstances. Over the following days unit members burned Pat’s body armor, uniform and other potential evidence, while officials doctored written statements for the Silver Star recommendation and lied to the press and the Tillman family. A week after Pat’s death Brig. Gen. Stanley McChrystal, the Joint Special Operations commander, sent senior government officials a confidential P4 memo mentioning fratricide—friendly fire—and warning civilian leadership to tread carefully. The story fell apart on May 24 when Rangers finally told Kevin what had happened.

In 2008 the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform released a report, “Misleading Information From the Battlefield: The Tillman and Lynch Episodes,” detailing the damage done by deliberate deception in both cases. “The bare minimum we owe our soldiers and their families is the truth,” said committee chairman Henry Waxman. “That didn’t happen for two of the most famous soldiers in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. For Jessica Lynch and Pat Tillman the government violated its basic responsibility.”

Yet the committee assigned little blame. Officials all the way up to former Defense Secretary Rumsfeld testified they could not recall many details. The highest official punished for the cover-up was retired Lt. Gen. Philip Kensinger, former commander of the Army Special Operations Command. The Army censured Kensinger for misleading investigators and stripped him of his third star, stating he knew about the fratricide even while attending Tillman’s May 3, 2004, memorial service.

Despite the tragic circumstances of Pat Tillman’s death and the subsequent shortfall in officialdom, Pat’s family honored his legacy of service by creating the Pat Tillman Foundation [pattillmanfoundation.org]. Still going strong, it provides scholarships and other support for service members, veterans and military spouses who want to parlay their education to serve their communities. MH

Paul X. Rutz, a former U.S. Navy officer, is a visual artist and freelance writer. For further reading he recommends Where Men Win Glory: The Odyssey of Pat Tillman, by Jon Krakauer, and Boots on the Ground by Dusk: My Tribute to Pat Tillman, by Mary Tillman.

This article appeared in the September 2021 issue of Military History magazine. For more stories, subscribe and visit us on Facebook: