Tennesseans re-create the national pastime the way soldiers played it

ON A SPRING DAY IN 1862, soldiers in opposing armies aimed to kill each other in farmer Joseph Duncan’s field at Shiloh. On the 157th anniversary of the first day of the battle in southwestern Tennessee, opposing forces merely want to outscore each other on the same turf. At the invitation of the National Park Service, teams in the Tennessee Association of Vintage Base Ball play a doubleheader on hallowed ground. Gods of sport smile: The sky is clear and the temperature tips into the 80s.

In an odd juxtaposition, a double play is turned yards from cannons that mark a Confederate artillery position and a monument for a Union brigade headquarters. Fans relax on lawn chairs and bales of hay, watching the players in Civil War–era baseball uniforms. Drinks and snacks are available from a stand behind a bench for ballplayers. Fastened to a portable backstop, a large U.S. flag flutters in a gentle breeze. Also attached to the barricade is a bell, intended to be rung by runners when they score. Nearby, a cannon booms during an artillery demonstration.

Players from the Quicksteps of Spring Hill, the Franklin Farriers, the Phoenix of East Nashville, and the Stones River Scouts toss and hit a slightly softer and slightly bigger cousin of the baseball we know. A white-bearded arbiter—we refer to him as an umpire or by a profanity—officiates. Like competitors during the war, the ballplayers don’t use gloves to catch the ball, called an “onion,” “pill,” “apple,” or “horsehide” some 150 years ago. A wooden bat? That’s a “willow.”

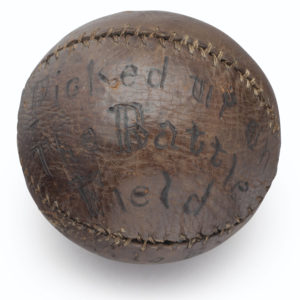

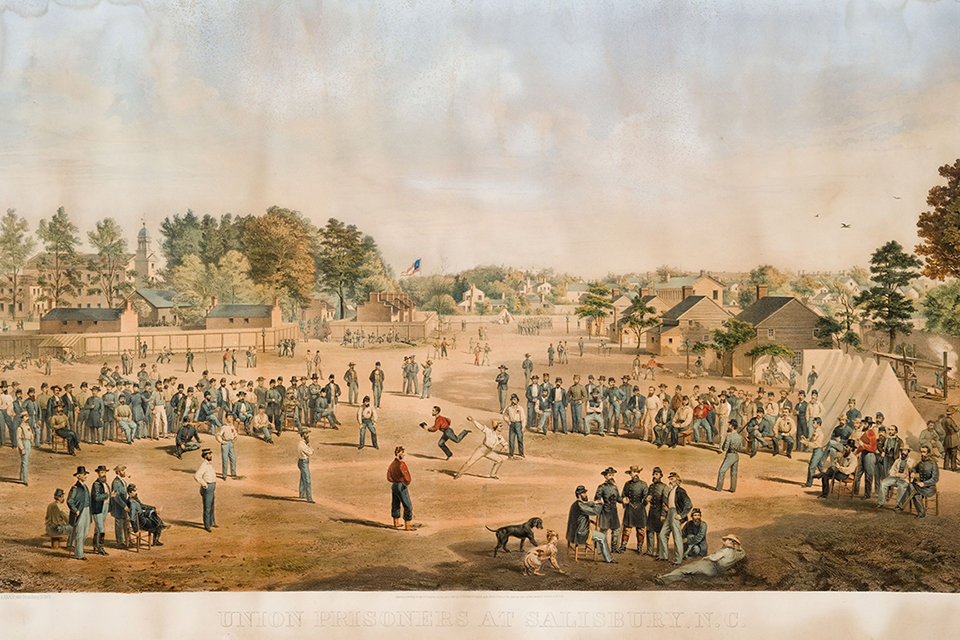

Baseball and Shiloh are not as unusual a mix as they may seem. During the war, soldiers played everywhere from battlefields to prison camps. A “lemon peel ball,” an early baseball that an African-American orderly retrieved after the Battle of Shiloh, was auctioned by Christie’s for $4,750 in 2017.

The Boys of Spring 2019 all have nicknames—“Meatball,” “Liberty,” “Spud,” “Mule,” and “Suspenders” are among my favorites. A burly slugger named “Lefty” considers the experience “awesome.” His teammates do, too. Wherever the spirits of the Boys of Spring 1862 linger, they must be pleased.

I’m smiling, too. My big-league dreams were crushed decades ago, but this Civil War–era game? Hey, where do I sign up?

But first, we need a brief Civil War baseball history lesson.

Like the balk rule, the roots of baseball in Tennessee are murky. A version of the game may have been played in Nashville as early as 1857. In the summer of 1860, months before the war broke out at Fort Sumter, the Nashville Republican Banner described a game called baseball as a “healthful and exciting exercise” that was “generally popular” in the North. Reported the Banner on July 25, 1860: “We noticed the other evening a party engaged in Base Ball on the Edgefield side of the [Cumberland] river, all apparently enjoying themselves. The early closing of the stores gives a fine opportunity to the young men engaged in mercantile pursuits.”

“Let us have Base Ball Clubs organized, then,” the paper added, “and the fun commenced.”

When the Federals occupied Nashville in March 1862, many soldiers frequented the notorious houses of ill repute on “Smokey Row,” near the State Capitol. Others partook in a more wholesome activity: baseball. “Surely the Yankee soldiers taught the locals how to play their version of baseball,” notes Nashville historian Skip Nipper.

Thirty-plus years before Babe Ruth was born, Yankees probably played baseball, or a distant cousin of the game called “town ball,” elsewhere in the Tennessee theater of war. A Union veteran would recall “many interesting games of base-ball” played by the soldiers in the 19th Illinois in “large cleared grounds” near Murfreesboro, site of the 1862 Battle of Stones River. He also described a game between the 69th Ohio and the Illinois boys. “This was the only strictly match game played between the two regiments during our stay in Murfreesboro,” he wrote, “but when not interfering with regimental or brigade drills or their duties, games were frequently played by members of each regiment on their own grounds until ‘marching orders’ came, and we ‘stole’ another base on Johnie.”

It’s game day at a field at The Hermitage, historic home of President Andrew Jackson. I am officially a Nashville Maroon. My nickname? “Flounder.”

For my debut, I wear a striped cap several sizes too small (borrowed), maroon pants with a white belt (borrowed), and an overly large white jersey with a maroon-and-white bib (borrowed) with a large “N” sewn on it. In a nod to the 21st century, I wear cleats from Nike, but fail to cover up the white Swoosh, a no-no. When I find out there was no designated hitter back then—meaning, aargh, playing a position in the field is required—desertion becomes an intriguing option. My aching hands weep after a gloveless catch while warming up with our shortstop, “Stitch.”

Before the first pitch, my teammates and the opposition—the Cumberland Base Ball Club of Nashville—doff caps and announce our nicknames to a small group of spectators: “Sticky Fingers,” “Shaky Leg,” “Peach,” and so forth.

During games, players must remain true to 1864, the time frame they represent. Teammates look at me strangely when I stuff my civi-lian clothes into an orange box and place it beneath the wooden bench. Not allowed, rookie. Those sunglasses? Remove them, sir. And manager James Guthrie—aka “Schoolboy”—gives me the business when I pull out my cellphone. Apparently the only way to communicate with my wife is by stringing telegraph wire to points unknown. Even the 21st-century soft dental pick sticking from my mouth is frowned upon.

The venue has a unique feature: an electrified cow fence just beyond barbed wire in left field. (Major League Baseball, please take note.) After I pop out in the first inning, I imagine my teammates conspiring to figure a way for me to receive “shock” therapy. I do get a charge from other facets of the 19th-century game: the terminology and rulebook. A batter is referred to as a “striker.” A run is called an “ace.” A home run is a “four baser.” “Ballist” is a slang term for ballplayer.

The 12-team Tennessee Association of Vintage Base Ball (TAOVBB) mostly abides by the rules adopted by the National Association of Base Ball Players on December 9, 1863, such as the pitcher must deliver the ball underhanded; a ball fielded on one bounce is an out. But my favorite league rule, which could lead to the collapse of American civilization if universally enforced, is at the discretion of an arbiter:

“In the spirit of sportsmanship, the players involved should determine the outcome of a given play. If no consensus can be reached, the respective captains will confer with the umpire. If there is still no consensus, the umpire may ask one spectator with a view of the play. The umpire’s word is final, and players may not complain or comment on that decision.”

Thankfully, I face no such call in my debut. Flounder’s final line: Four at-bats, one hit, one pulled groin.

While playing in the 8th grade, Tennessee Association of Vintage Base Ball co-founder Trapper Haskins lost a pickoff throw in the lights. The ball crashed into his face, knocking out three of his front teeth. “I remember spitting them out on the dirt,” he says.

Understandably, Haskins lost interest in baseball for decades, but in 2007, while working in Port Huron, Mich., he saw a flier for a vintage baseball league seeking players. He joined and was hooked. “Just playing with those guys, celebrating the history of the game, it was special,” says Haskins, 42. “It’s the game reduced to its barest form.”

Back in his native Tennessee five years later, Haskins discussed with others putting together a vintage league. “This ain’t your daddy’s baseball game,” read the posters they put up. “It’s actually your great-great-great-great granddaddy’s baseball game.”

On a snowy day in the winter of 2012-13, about 20 people showed for the league’s initial meeting in East Nashville. All signed up to play. There were two teams the summer of 2013; others were quickly added in Chattanooga, Knoxville, Spring Hill, and Franklin—all places with rich, and bloody, Civil War history.

The average age of players is 42. One is 19, a few in their early 70s. Most appreciate Civil War history and baseball in its purest form. Rosters, which allow up to 15 players a team, include an architect, a barber, a former minor league baseball player, and a retired railroad worker known as “Caboose.” My Maroons have one female player, “Law.”

“I’d be lying if I knew then what it would become,” says Haskins, who has a collateral ancestor who served in John Bell Hood’s Army of Tennessee.

As in the Civil War era, gentlemanly behavior is stressed. In a game at the Oaklands Plantation in Murfreesboro, the Stones River Scouts and Maroons dueled about 150 yards or so from where Nathan Bedford Forrest surprised Union cavalry in July 1862. “It is better to play this game with all your heart can give,” Nipper, the arbiter, tells the players before the game. “Whether home run, out or error, fair play is how we live.”

The league’s most impressive venue is the Carnton Plantation in Franklin. On November 30, 1864, Hood’s soldiers swept across the property during a disastrous defeat at the Battle of Franklin. Games there are played at a large field next to the plantation mansion and 50 or so yards from the hallowed McGavock

Confederate Cemetery.

Some fields, Haskins admits, are quirky and imperfect. A “little lumpy, tilted a little bit,” he says. An apt metaphor, no doubt, for a tumultuous Civil War era.

Nashville-based John Banks is author of John Banks’ Civil War Blog (john-banks.blogspot.com). A shorter version of this column first appeared on April 7, 2019.