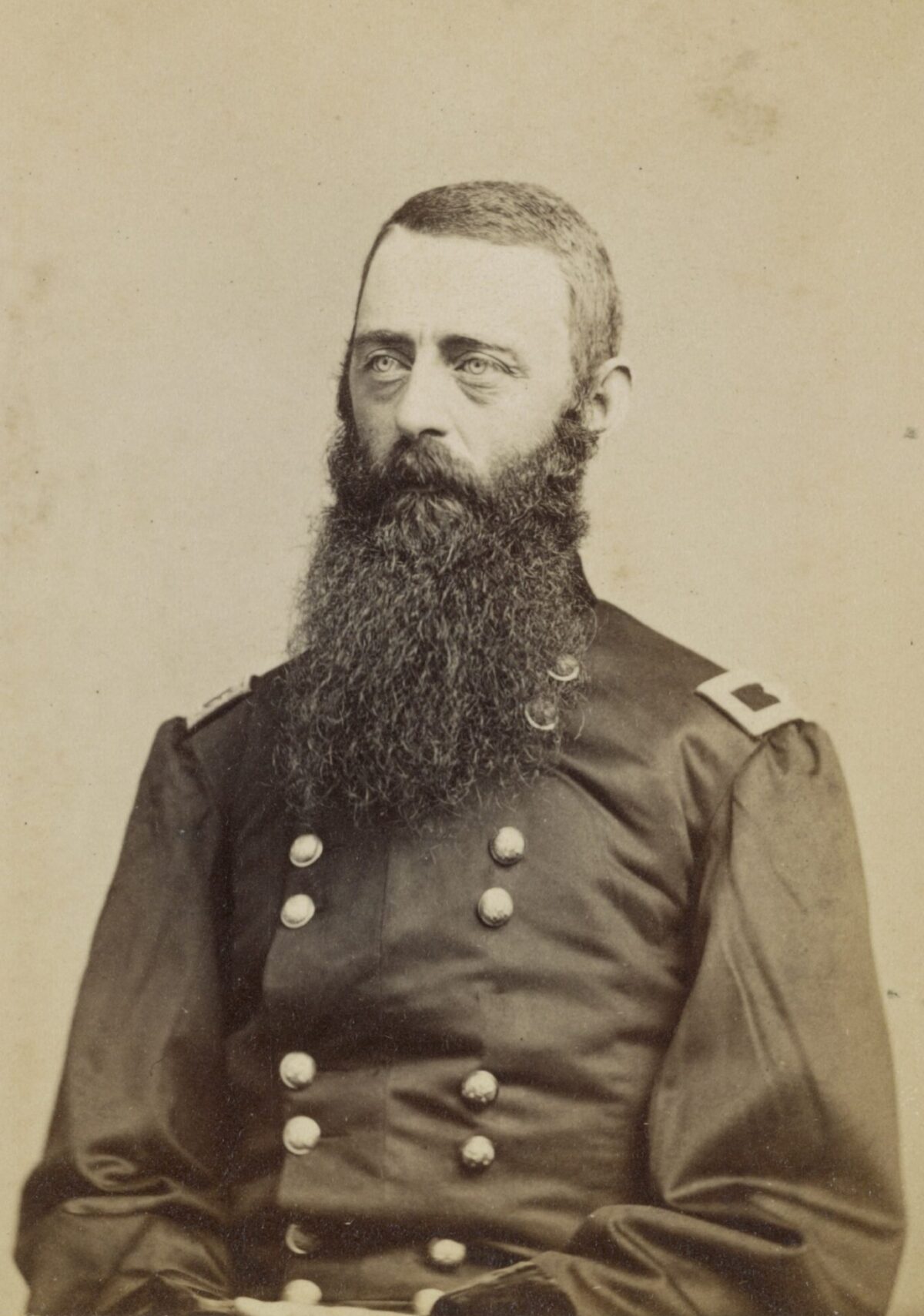

Edward G. Longacre is an award-winning historian with more than 30 books covering a variety of Civil War subjects. He is best known for his work on Union cavalry operations and biographies of Union and Confederate cavalry commanders, including Fitzhugh Lee, Wade Hampton, John Buford, and James H. Wilson. He is currently at work on the final volume of a trilogy on the life and legacy of George Armstrong Custer. In Unsung Hero of Gettysburg (Potomac Books, 2021) he gives David McMurtrie Gregg—an outstanding but underappreciated cavalry officer—a biography worthy of a soldier who served his country with unfailing dignity and unpretentiousness.

Edward G. Longacre is an award-winning historian with more than 30 books covering a variety of Civil War subjects. He is best known for his work on Union cavalry operations and biographies of Union and Confederate cavalry commanders, including Fitzhugh Lee, Wade Hampton, John Buford, and James H. Wilson. He is currently at work on the final volume of a trilogy on the life and legacy of George Armstrong Custer. In Unsung Hero of Gettysburg (Potomac Books, 2021) he gives David McMurtrie Gregg—an outstanding but underappreciated cavalry officer—a biography worthy of a soldier who served his country with unfailing dignity and unpretentiousness.

You were a historian for the Department of Defense. What got you interested in the Civil War?

I worked as an Air Force historian for 29 years, first at Headquarters Strategic Air Command and later at Headquarters Air Combat Command. It made for an interesting mix of subjects; writing Air Force history, much of it top secret, by day and Civil War history at night. My interest in the Civil War derives from my discovery in high school that I had a great grandfather in the Union army. I knew I wanted to be a writer since I was seven years old and I found my subject in 11th grade.

You seem drawn to cavalrymen. Do you have a favorite?

I don’t know that I have a favorite but I find myself drawn to the abilities and personality of George Armstrong Custer. My interest in cavalrymen is mostly personal. My great-grandfather was a sergeant in the 5th Pennsylvania Cavalry, a unit mustered in Philadelphia in 1861. A host of other ancestors were also horse soldiers, mostly on the Confederate side. Five served in various Missouri regiments; two others were in the 11th Virginia under J.E.B. Stuart. Another relative was the colonel of the 2nd Arkansas Mounted Rifles and, with some reticence, I admit that yet another relation, Charles Longacre, was a charter member of Quantrill’s Raiders.

Why did you choose to write about David McMurtrie Gregg?

I’ve been interested in Gregg ever since I was a college freshman and began researching operations of the Union cavalry. My interest in Gregg specifically was heightened years later when, pursuing my doctorate in American history, I had the good fortune to study under the late Professor Russell F. Weigley, generally regarded as one of America’s finest military historians. Russ grew up in Gregg’s adopted hometown of Reading, Pa. As a teenager, he cut the grass at the local cemetery, where he paid special attention to the general’s grave and began studying his life. More than once I heard him say that Gregg deserved a full-length biography; the suggestion resonated with me.

You call David Gregg the beau ideal of a Civil War cavalryman. What made him an effective cavalry commander?

First off, Gregg had all the prerequisites for success as a mounted officer: a first-class education at West Point, post-graduate training at the Cavalry School at Jefferson Barracks, Mo., and distinguished service against Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest. A consummate professional, he never allowed ego or ambition to influence his actions, and he bore no ill will toward colleagues of lesser ability who gained higher rank and authority through military or political connections. His determination to advance his career through performance rather than personality—in contrast to such flamboyant self-promoters as George Custer, J.E.B. Stuart, and Judson Kilpatrick—stands as perhaps his most notable trait. Although not a tactical innovator, he grew and evolved professionally as the war progressed, giving greater emphasis to dismounted fighting over saber charges. By late 1864, he was relying heavily on mixed formations, fighting his men mounted and dismounted in rapid sequence. He was also adept at utilizing the horse artillery units attached to his brigades and divisions. Throughout the war he held the confidence and respect of every superior, and the trust and affection of his troopers. One veteran spoke for many of his comrades when he wrote that while their old commander was noted “as being the most tenacious cavalry fighter of the war, they felt that he was watching over them and that not a life would be sacrificed needlessly.”

Describe Gregg’s relationship with Custer. Was he angry or jealous Custer got so much acclaim for Union success in East Cavalry Field on July 3, 1863?

As far as I know, Gregg never expressed any jealousy toward Custer. On the contrary, he was highly appreciative of Custer’s contribution in halting Stuart’s advance toward the Union right and rear on Gettysburg’s third day. For his part, Custer always spoke highly of Gregg’s leadership, as did many of his men. The Federals foiled Stuart’s grand effort to turn the Union flank and strike from the rear, and Gregg, more than any other man on the field, including Custer, had seen to it. Gregg had additional grounds for being in debt to Custer, whose critical support during the seven-hour Haw’s Shop struggle on May 28, 1864, prevented Gregg’s outnumbered and hard-pressed command from being driven from the battlefield. By the way, Haw’s Shop has its own niche in the history books. It was the largest and most fiercely contested dismounted cavalry engagement of the war.

What happened to Gregg immediately after Gettysburg?

The best answer is that no one knows for sure. For almost a week following the battle, he disappeared almost entirely from the official record. Even Gregg’s own after-action report of the campaign fails to address his status during this period. His division was broken into three parts that were detached from him and assigned to other commanders, including infantry generals, in order to pursue the retreating Confederates. These events do not appear to be a form of punishment. In fact, he received praise rather than censure from his superiors, including Meade’s chief of staff, Daniel Butterfield, for his activities on July 2-3. Perhaps Gregg’s absence had to do with his sometimes fragile health, including undiagnosed fainting spells and debilitating fevers, that plagued him throughout the war and forced him to go on sick leave. There is no report, however, of him taking medical leave during this period.

Do you think the accusations that Gregg made tactical mistakes at Bristoe Station were justified?

I do. Early on October 12, 1863, Gregg was directed by army headquarters to report, as soon as possible, any Confederate attempt to turn the Union right flank and gain its rear, thereby interposing itself between Federal forces and Washington, DC. General Lee hoped to do just that. When Gregg’s division became embroiled in heavy fighting that morning near Sulphur Springs, Va., it monopolized Gregg’s attention and he failed to get a report to headquarters until almost 10 hours after first becoming engaged. The delay could have spelled disaster for the Union Army. General Meade managed to pull The Army of the Potomac out of danger only at the eleventh hour. While it’s understandable that Gregg was pre-occupied by the heavy fighting on his front where his command lost heavily and was nearly overwhelmed, he should have adhered to his orders. Meade’s headquarters was only 10 miles away at the time, making Gregg’s lapse that much worse. Major General Andrew A, Humphreys, Meade’s chief of staff at the time, was livid over Gregg’s performance. According to Humphries’ son, writing almost 40 years after the war, his father suggested that Gregg be tried by drum head court-martial and shot for his dereliction. This was, of course, an overreaction, but fears and tempers were running high that day.

Was there really bad blood between Gregg and General Philip Sheridan?

Not that I can determine. Supposedly the two officers, who admittedly were very different in temperament and leadership style, clashed in a way that prevented their cordial cooperation. Some historians believe that Gregg submitted his resignation from the army on the eve of the Appomattox Campaign because he did not wish to serve again under Sheridan who was about to return to the Petersburg front after six months of campaigning in the Shenandoah Valley. David M. Gregg, Jr., who wrote an unpublished account of his father’s wartime service, vehemently denied that his father expressed any reservations about serving under Sheridan. Sheridan himself praised Gregg highly in his own published memoirs. One telling point is that as Sheridan prepared to go to the Valley in August 1864, Gregg wrote army headquarters offering his division as part of Little Phil’s command. By this point he had been serving under Sheridan for four months, long enough to know whether he could have continued the relationship without loss of honor or self-respect.

Did Gregg strive to reestablish his reputation after the war or was he content to let the record speak for itself?

While Gregg made no overt attempt to solidify or bolster his reputation—he published no memoir of his service and the few public talks he gave focused not on himself but on the troops he led—he did try to regain a position in the ranks. When the postwar Army was enlarged, he avidly sought the colonelcy of one of the new cavalry regiments but, perhaps due to his early exit from the war, the appointment went instead to his cousin and wartime subordinate, J. Irvin Gregg. His postwar life was, in some ways, a study in rootlessness. He never owned a home of his own—he, his wife, and their two sons lived in a series of rented houses, hotel rooms, and resort cottages. Rarely, and only for brief periods, did he have a paying job. In 1874, President Grant appointed him U.S. consul in Prague, but he gave up the post in less than five months when his wife became desperately homesick. In 1891, he was elected to a four-year term as auditor general of his native Pennsylvania, his only stint in political office. His postwar finances must have been a continuing concern, especially when a bill to provide him with a pension twice failed in Congress. A fellow cavalry historian who read my book in manuscript came away feeling that Gregg’s postwar years must have been lonely ones. That had not occurred to me, but I think he’s right.