American agents battled opium smugglers cramming contraband into steamers headed for San Francisco Bay

IN A WHALEBOAT being cast about by currents near the mouth of San Francisco Bay, Second Lieutenant Thomas W. Benham urged his oarsmen to pull hard for the steamer Gaelic, now making for the main shipping channel. Rain was falling, hard and cold, that early morning of Thursday, December 9, 1886, but at least the gale-force winds and fog had abated. The whaleboat belonged to the U.S. revenue cutter Richard Rush, whose captain had sheltered his ship on the south shore, out of the blow. The coxswain was easing the whaleboat into the steamer’s wake when from the ship’s stern lines lowered four large objects. Oarsmen snagged the packages with boathooks. Wrestled aboard, the items revealed themselves to contain some 500 lbs. of opium packed in ½-lb. tins. Rush crewmen, acting on intelligence from U.S. Treasury agents in Hong Kong, had made their second seizure of illegal drugs at sea in two weeks.

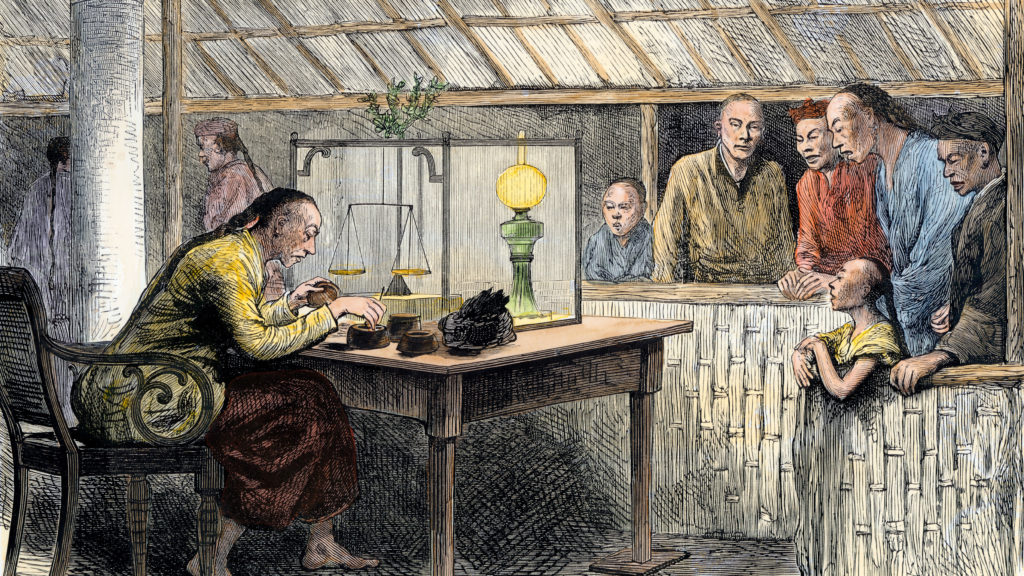

Introduced in the 1850s as a painkiller—its use by the military during the Civil War greatly expanded familiarity with its effects—opium quickly became big business. Tons of the stuff flowed legitimately through San Francisco to be processed into laudanum—opium dissolved in alcohol, sipped to dull pain, suppress coughs, fight depression, aid sleep, and generally enhance a user’s mood—and other popular drugstore tonics. Some opium was refined for sale to be smoked, usually by Chinese laborers brought to the United States to build the Transcontinental Railroad. These immigrants’ habits did not trouble official America until white Americans in great numbers developed opium habits.

Americans were using significant amounts of Chinese-made opium in the mid-1880s when the United States imposed a heavy tariff on the drug. Drug merchants set up networks that flooded western ports with outlaw opium from the East, initially secreting contraband in freight and luggage and on passengers’ persons. Customs inspectors based at San Francisco grew adept at winkling out these caches, so smugglers shifted to offloading opium at sea.

Intended to protect the historic medicinal opium industry, the federal crackdown sought to smother smuggling of raw opium without banning the drug. In the 1880 Treaty Concerning Commercial Intercourse and Judicial Procedure, the United States and China agreed that “Chinese subjects shall not be permitted to import opium into any of the ports of the United States.” The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 barred entry to skilled and unskilled Chinese and required resident Chinese leaving the United States to obtain certifications to reenter (“Angel Island,” American History, December 2016).

When neither law made opium smoking less popular, federal officials decided to ban import of opium to be refined for smoking and to try to tax opium out of existence, imposing an import duty of $10 per lb.—roughly a 100 percent markup. The duty on raw opium used domestically in consumer products and pharmaceuticals remained at $1 per pound. This measure proved the law of unintended consequences. Profits soared on refined opium smuggled stateside. Customs inspectors came to assume opium in some form was hidden someplace on every ship bound from Hong Kong to San Francisco, less frequently by ships’ personnel than by passengers. Luggage could hold 60 lb. of contraband. Crooked sailors hid larger loads in berthing areas, machinery spaces, cargo holds, and bilges. The usual punishment was losing a load to confiscation. Only repeat offenders were arrested, and since ships’ officers and owners rarely were in on the crime, the authorities rarely assessed fines or seized vessels.

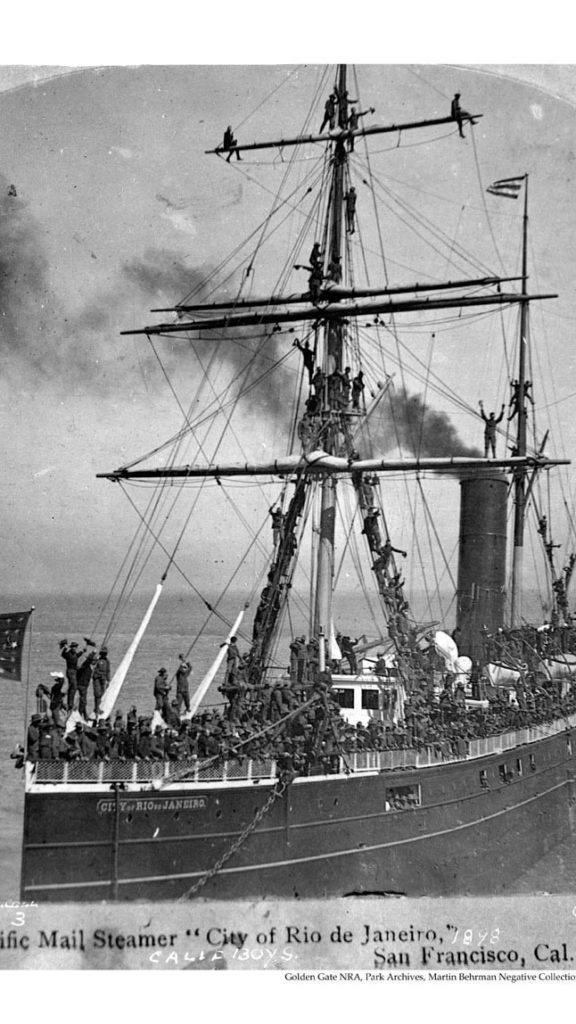

The story of SS City of Rio De Janeiro is illustrative. Launched in 1878 at Chester, Pennsylvania, the 345-foot, 3,548-ton steamer joined the Pacific Mail Steamship Company fleet in 1881. Rio plied a circuit taking it to Hong Kong (ceded to Britain in 1842), Yokohama, Japan, and San Francisco, California, carrying passengers, cargo, mail—and opium. Arriving from Hong Kong in June 1884 at San Francisco, Rio was found by customs inspectors to have 40 pounds of undeclared opium aboard. Frequency and size of smuggled loads aboard Rio led authorities to focus on the ship after every trip overseas. During this period, the U.S. Treasury Department placed agents at Hong Kong and Yokohama to gather intelligence for customs inspectors.

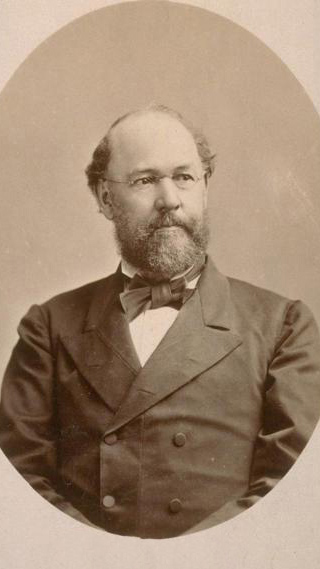

In November 1886, Treasury agents in Hong Kong wired the San Francisco collector of customs, John S. Hager, reporting that smugglers aboard Rio had a new dodge. “Judge” Hager had trained as a lawyer, served as a state district judge, and represented California in the U.S. Senate as a Democrat 1873-75.He got his customs job through politics, not experience in nautical or shipping matters. Nonetheless, he was good at it. Learning that rather than squirreling away contraband in hopes that inspectors would miss it, the smugglers planned somehow to offload the opium before the steamship entered port, Hager assigned the deputy surveyor of the port, John T. Fogarty, his former secretary,to disrupt the plan and seize the drugs. As a U.S. marshal, Fogarty had run many opium smuggling investigations and knew the ins and outs of interagency cooperation.

To break up that party, Fogarty had to enlist the Revenue Marine Service, a branch of the Treasury Department. Originally the Revenue Cutter Service, the Revenue Marine, a predecessor of the Coast Guard, rescued occupants of sinking vessels, assisted foundering ships and others in trouble, and dueled with smugglers.

The Revenue Marine and Customs Services regularly interacted in port. Revenue cutters often provided personnel and nautical expertise when Customs needed assistance dockside. Customs officers often rode aboard cutters and participated in boardings at sea of suspicious vessels—usually in response to intelligence they themselves had provided. Fogarty contacted Captain Calvin L. Hooper of U.S. Revenue Cutter Rush, based in San Francisco to cover the whole California coast.

Technically classified a “propeller steamer,” Rush was a hybrid meld of sail and steam, combining a classic topsail schooner’s sleek hull and twin masts with a coal-fired steam engine, betrayed by a tall exhaust funnel and pilothouse amidships. As armament the cutter mounted 6-lb. deck guns on its forecastle and fantail. Rush’s 175-foot hull was less than a year old; the 300-tonner’s engine a salvage job. With steam up the cutter made the same nine knots as under sail, but without a worry about the wind. The dual power configuration was a nod toward economy—at full steam, the cutter burned more than six and a half tons of heavy, costly coal a day. The Revenue Marine was trying to chase steamers that could hit 12 to 15 knots with vessels barely able to surpass half that speed.

Gauging Rio de Janeiro’s arrival, Fogarty and four customs inspectors joined Rush’s seven officers and 24 enlisted men on the pleasant, clear morning of Sunday, November 28, 1886. At 8:30 a.m. Captain Hooper ordered his ship outbound into the main channel.

Few bays can match San Francisco’s for oceanic treachery. A bar of shallows begins off the northern shore of the Bay’s mouth, arcs in a rough semicircle five miles seaward, and then curves back to the southern shoreline. Waves, currents, and the shallows create ship-smashing breakers that have claimed many a vessel whose crew tried to cross the bar rather than use the shipping channel that bisects the western end of the bar.

That morning the wind and sea were calm and the temperature a balmy 58°. By mid-morning the cutter was safely past the bar and slowly patrolling a six-mile course from the southwest to the northeast and back, reversing direction hourly. The aim was to cover the approach to the harbor channel. In the afternoon, the wind picked up. Crewmen cut the engine and set all sail except staysails and topsail. For two days of light winds, calm seas, Rush patrolled, alternating sail and steam. Officers and crew conducted several routine boardings of inbound steamers but saw no sign of Rio de Janeiro.

November 30 seemed to be delivering more of the same until the wind rose out of the northeast and fog rolled in, complicating the exercise. Despite reduced visibility, at midmorning, spotters saw a steamer. Rush got a boat alongside. Second and Third Lieutenants Benham and Horace B. West, Second Assistant Engineer Paul Barnes, Deputy Surveyor Fogarty, and three customs inspectors scrambled aboard Rio de Janeiro. As the vessel made for the bay, the officials conducted an inspection. The cutter, running full sail and full steam, straggled behind the larger, faster steamship for 90 minutes. Just before Rio was to moor, a steam pipe aboard the cutter broke, causing her to stop escorting Rio and anchor nearby. Engineers set to work but had to send the damaged part ashore the next day for repairs.

The men of the boarding party from the cutter reported finding 350 lbs. of opium at Rio de Janeiro’s stern, apparently ready to be offloaded. No evidence linked anyone aboard to the stash. Authorities turned the steamer loose. But the seizure offered several lessons. The packaging confirmed the scheme’s structure. Each box of 20 tins, each tin holding roughly 8 oz. of prepared opium, was cushioned in a blanket made waterproof with oilcloth. To each box was affixed a buoy and a reel of line. The fog that had complicated the Rush’s intercept likely had prevented the smugglers from sighting their contact, keeping them from lowering their illicit load.

Forewarned, Captain Hooper was ready when Fogarty again approached him in early December. Treasury agents in Hong Kong had telegraphed that SS Gaelic was carrying concealed aboard a large load of opium they planned to bring ashore in the same way as had been attempted by operatives aboard Rio de Janeiro. Gaelic worked the same circuit as Rio—and previously had been caught carrying contraband. Fogarty and three inspectors boarded Rush at 10:55 a.m. December 7, a foggy, rainy Tuesday. Captain Hooper ordered a speed of “one bell”—around three knots—outbound through the bay.

After crossing the bar, Hooper again patrolled the channel entrance. The fog intensified such that in late afternoon he anchored off the south shore of Point Bonita. At evening he sent a whaleboat with one of his officers and a customs inspector to check the shoreline to the north for boats intending to meet Gaelic. A second boat cruised the edge of the channel. Both small craft returned by midnight, having sighted nothing. Rush remained at anchor but on alert all night.

In the morning, a boat checked the shoreline. The wind grew to a strong breeze from the south-southeast, clearing the fog but bringing rain squalls. The seas began to rise. Rush got under way, retrieved the whaleboat, and steamed the bar to resume patrolling.

By early afternoon, the fog had returned with a strong gale, prompting Captain Hooper to anchor Rush off the South Shore in 18 fathoms—108 feet—of water. During a lull, Rush headed for the channel entrance, but conditions worsened, against forcing the cutter to seek shelter in a lee near the South Shore.

At 2:30 a.m. Thursday, a lookout sighted lights on an inbound steamer. Lieutenant Benham maneuvered his whaleboat at the unidentified vessel’s stern, getting close enough to confirm it was Gaelic—just as objects descended from the ship’s deck almost into his lap. The smugglers thought the Revenue Marine cutter was their contact. Cutter men at the small boat’s bow grabbed the packages with boathooks and pulled them aboard. Each contained more than 100 lbs. of opium in tins.

From Rush, Captain Hooper fired a blank from his forward gun, signaling Gaelic to halt. When the transport did so, Rush escorted Gaelic to an anchorage and Benham transferred Fogarty and the customs inspectors to the steamer. Crewmen in boats spent hours searching adjoining waters and nearby vessels while customs officers searched Gaelic. No other contraband turned up. No smugglers were identified. The collector of customs took custody of the confiscated opium. Rush crewmen spread and tossed the cutter’s sails to dry under a clear sky, then went on well-deserved liberty.

The Rush seizures and their prototype interagency cooperation discouraged opium smuggling at San Francisco, but the practice persisted, shifting to coastal freighters and fishing sloops out of Victoria, British Columbia. There, legitimately landed opium could be run less than 40 miles across Puget Sound to Port Townsend and other locations in Washington Territory. The cat and mouse game had begun.