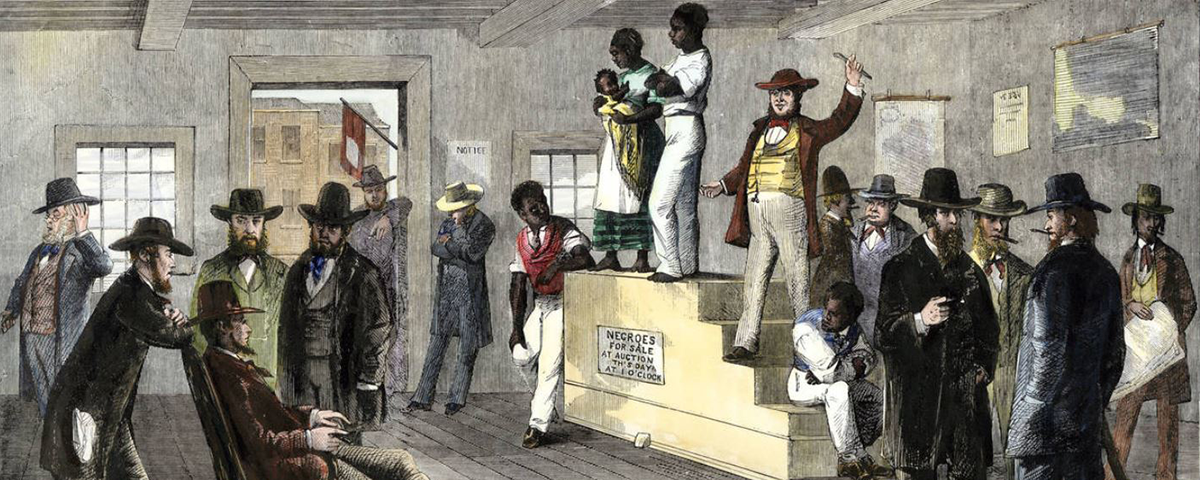

FROM THE PLATFORM, auctioneer William Walsh greeted the 200 bidders milling in the large hall with one side open to cold March winds and announced the first item for sale—a Negro family standing on the platform, available for inspection. Would-be purchasers studied the catalogue, which identified the lot on offer:

- George, age 27, Prime Cotton Planter

- Sue, 26, Prime Cotton Planter

- George, 6, Boy Child

- Harry, 2, Boy Child

Walsh started the bidding at $300 per head, cajoling the men milling on the floor to compete with one another until somebody had bought the whole family for $2,400. As the slaves stepped down to meet their new owner, Walsh gaveled the next lot onto the platform. Bidders carefully inspected the slaves, checking arm and leg muscles, ordering each to walk and squat, pulling open mouths to reveal teeth. A slave named Primus stepped onto the platform with his wife Daphney, their three-year old daughter, and a newborn. Daphney had wrapped a

blanket around her shoulders and the baby she clutched to her breast. This pose irked some bidders.

“What do you keep your n—— covered up for?” one bidder yelled. “Pull off her blanket.”

“What’s the matter with the gal?” another man said. “Ain’t she sound? Pull off her rags and let’s see her.”

The auctioneer explained that the mother was merely trying to keep her baby, born only 15 days earlier, warm. Daphney removed the blanket, exposing her child and herself. The family sold for $2,500.

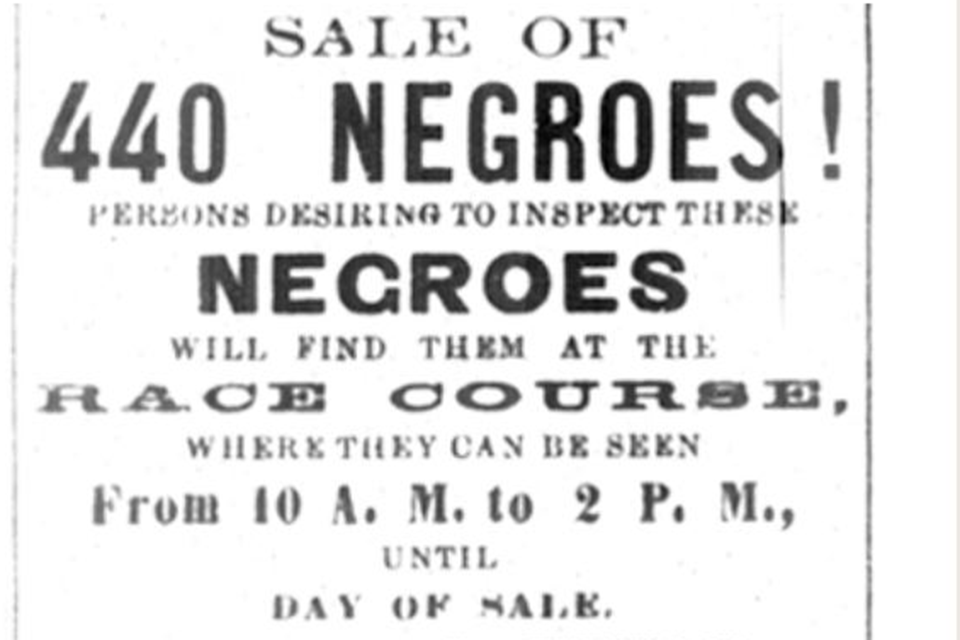

It was March 2, 1859. At Ten Broeck racetrack outside Savannah, Georgia, Pierce M. Butler, a playboy from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, was selling 429 slaves. The sale was taking place under duress.

In the 1820s, Butler’s grandfather, also Pierce Butler—Founding Father, hero of the Revolution, U.S. senator—had left his namesake

and the boy’s older brother John plantations totaling 10,000 acres on Butler Island and St. Simon’s Island, Georgia, along with the hundreds of Negroes who worked those cotton, rice, and tobacco fields. To inherit this fortune, the youths had only to change their family name, Mease, to Butler. The boys did so, divvying ownership of the slaves. In 1834, Pierce Butler married British actress Fanny Kemble. An abolitionist as well as a celebrity, Kemble was appalled by the treatment accorded her husband’s slaves. The couple argued over the matter. Later, back in Philadelphia, Kemble caught Butler cheating. Their 1845 divorce cost him plenty, and then he squandered what remained of his fortune on the stock market and the high life.

Deep in debt by 1859, the profligate planter sold his Philadelphia mansion. But his debts outran those proceeds, so he decided to liquefy another asset: his half of the island plantations’ work force. The United States had outlawed the importing of slaves in 1808; in the ensuing decades bondsmen had become a valuable commodity across the South. Now, Butler decided, auctioning his 429 slaves could save him from bankruptcy. His one concession to human decency: Though slave dealers commonly broke up families, Butler insisted that husbands were not to be separated from wives; parents and young children were to be kept together.

The Butler auction, managed by slave dealer Joseph Bryan, was the largest such event staged in the country in years, perhaps the largest ever. The proceedings at Ten Broeck attracted hundreds of planters and slave dealers, as well as Mortimer Thomson, a correspondent for the New York Tribune, Horace Greeley’s newspaper. Like many journalists of the era, Thomson wrote under a goofy pseudonym—Q.K. Philander Doesticks. He usually contributed humorous pieces—about fortunetellers, boxers, bohemians, and P.T. Barnum’s baby beauty contest. This time the assignment was deadly serious.

Southerners detested the Tribune for its frequent denunciations of slavery, so Thomson posed as a prospective bidder. He arrived early in Savannah and for days sauntered the racetrack grounds, watching buyers inspect slaves housed temporarily in stalls usually reserved for horses. Like the slave dealers, Thomson used his copy of the catalogue to make notes, surreptitiously transcribing conversations he overheard.

“Well, Colonel, I see you looking sharp at Shoemaker Bill’s Sally,” one buyer said to another. “Going to buy her?”

“I think not,” the other man replied. “Sally’s a good, big strapping gal, and can do a heap o’ work, but it’s five years since she had any children. She’s done breeding, I reckon.”

Throughout the two-day auction, a cold rain blew into the hall where bidding took place. Bidders warmed themselves with whiskey sold at a bar downstairs. The slaves could only shiver. Thomson closely watched black men and women as bidders vied to acquire them. Some slaves “regarded the sale with perfect indifference, never making a motion,” the newsman wrote. “Others strained their eyes with eager glances

from one buyer to another as the bidding went on…Sometimes two persons only would be bidding for the same chattel, all the others having resigned the contest, and then the poor creature on the block, conceiving instantaneous preference for one of the buyers over the other, would regard the rivalry with the intensest interest, the expression of his face changing with every bid, settling into a half smile of joy if the favorite buyer persevered and secured the property, and settling down into a look of hopeless despair if the other won the victory.”

By the end of the sale’s second day, auctioneer Walsh had sold all 429 slaves for a total of $303,850—about $700 per man, woman and child. The auctioneer popped corks on bottles of Champagne. Buyers sipped the bubbly while Pierce Butler strolled among his former chattels, handing each a parting gift of four shiny 25-cent pieces fresh from the Philadelphia mint. Thomson caught a New York-bound train and started writing. Instead of his usual comedic skylarking, he simply described what he had seen and quoted what he had heard, striking a tone of muted outrage and understated irony:

“Guy, chattel No. 419, ‘a prime young man,’ sold for $1,280, being without blemish; his age was twenty years, and he was altogether a fine article. His next-door neighbor, Andrew, chattel No. 420, was his very counterpart in all marketable points, in size, age, skill, and everything, save that he had lost his right eye. Andrew sold for only $1,040, from which we argue that the market value of the right eye in the Southern country is $240.”

Thomson lost his cool only when describing buyers making smutty wisecracks while pawing female slaves: “This sort of thing makes Northern blood boil, and Northern fists clench with a laudable desire to hit somebody. It was almost too much for endurance to stand and see those brutal slave-drivers pushing the women about, pulling their lips apart with their not too cleanly hands, and committing many another indecent act, while the husbands, fathers and brothers of those women were compelled to witness these things, without the power to resent the outrage.”

On March 9, 1859, the Tribune published Thomson’s 9,000-word article under an ironic headline: “American Civilization Illustrated.” Two

days later, by popular demand, the Tribune reprinted the story. Soon Thomson’s chronicle of the great slave sale was appearing in newspapers around the North, and in the Times of London. The American Anti-Slavery Society published the article in pamphlet form. Thomson went back to his beat. Two years later, when civil war broke out, he covered the conflict for the Tribune.

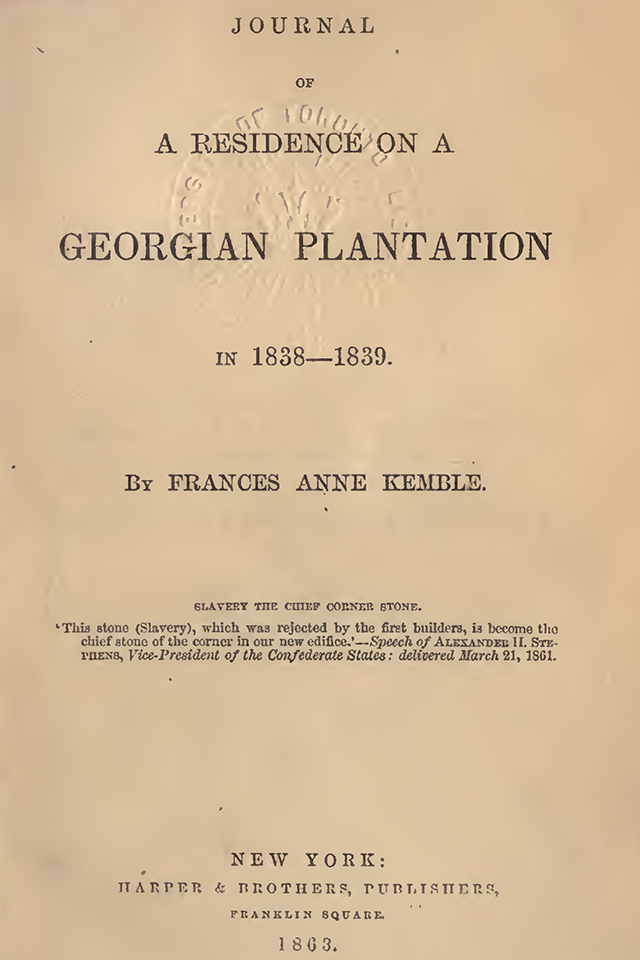

The Ten Broeck auction dispersed Butler’s former property to new locations across the South and financed a lengthy European vacation for their former owner. In 1863, Fanny Kemble, 18 years divorced from Butler, published Journal of a Residence on a Georgia Plantation, a book composed of letters she’d written 25 years earlier detailing the wretched lives of the black men and women she had observed on Butler Island and St. Simon’s Island in 1839. Journal became a bestseller in America and England, prompting another repackaging of Thomson’s article, this time as a slender volume billed as A Sequel To Mrs. Kemble’s Journal.

After the war, Butler returned to Georgia to manage his plantations, the land now worked by gangs of sharecroppers that included many of his brother’s former slaves. He died of malaria in 1867. His ex-wife, famed as an actress, playwright, poet, and memoirist, outlived him by 26 years. Thomson died in New York in 1875. Like most reporters, he was quickly forgotten—a fate he shared with the 429 slaves sold on the two days that came to be known as “the weeping time.”

_____

Up from the Stacks

Famous in its day, Mortimer Thomson’s article sank out of sight, available only in libraries inclined to keep obscure old books or microfilms of the New York Tribune. Digitized online, the original is available at publicdomainreview.org/collections/what-became-of-the-slaves-on-a-georgia-plantation-1863/. A brief excerpt:

THE LOVE STORY OF JEFFREY AND DORCAS

By Mortimer Thomson

Jeffrey, chattel No. 319, marked as a “prime cotton hand,” aged 23 years, was put up. Jeffrey being a likely lad, the competition was high. The first bid was $1,100, and he was finally sold for $1,310. Jeffrey was sold alone; he had no encumbrance in the shape of an aged father or mother, who must necessarily be sold with him; nor had he any children, for Jeffrey was not married. But Jeffrey, chattel No 319, being human in his affections, had dared to cherish a love for Dorcas, chattel No. 278; and Dorcas, not having the fear of her master before her eyes, had given her heart to Jeffrey…. Jeffrey and Dorcas had told their loves, had exchanged their simple vows, and were betrothed…

Be that as it may, Jeffrey was sold. He finds his new master; and, hat in hand, the big tears standing in his eyes, and his voice trembling with emotion, he stands before that master and tells his simple story, praying that his betrothed may be bought with him. Though his voice trembles, there is no embarrassment in his manner; his fears have killed all the bashfulness that would naturally attend such a recital to a stranger, and before unsympathetic witnesses. He feels that he is pleading for the happiness of her he loves, as well as his own, and his tale is told in a frank and manly way.

“I loves Dorcas, young Mas’r. I loves her well and true. She says she loves me and I know she does. De good Lord knows I loves her better than I loves anyone in de wide world—never can love another woman half so well. Please buy Dorcas, Mas’r. We’re be good servants to you as long as we live. We’re be married right soon, young Mas’r, and de chillum will be healthy and strong, Mas’r, and dey’ll be good servants, too. Please buy Dorcas, young Mas’r.”

Jeffrey then remembers that no loves and hopes of his are to enter into the bargain at all, but in the earnestness of his love he has forgotten to base his plea on other grounds till now, when he bethinks him and continues, with his voice not trembling now, save with eagerness to prove how worthy of many dollars is the maiden of his heart.

“Young Mas’r, Dorcas prime woman—A-1 woman, sir. Tall gal, sir, long arms, strong, healthy and can do a heap of work in a day. She is one of the best rice hands on de whole plantation, worth $1,200 easy, Mas’r, and first rate bargain at that.”

The man seems touched by Jeffrey’s last remarks, and bids him fetch out his gal. “Let’s see what she looks like.”

Jeffrey goes into the long room, and presently returns with Dorcas, looking very sad and self-possessed, without a particle of embarrassment at the trying position in which she is placed. She makes the accustomed curtsy and stands meekly with her hands clasped across her bosom, waiting the result. The buyer regards her with a critical eye, and growls in a low voice that “the gal has good points.” Then he goes on to a more minute and careful examination of her working abilities. He turns her around, makes her stoop and walk; and then takes off her turban to look at her head, that no wound or disease be concealed by the gay handkerchief. He looks at her teeth, and feels her arms, and at last announces himself pleased with the results of his observations. Jeffrey, who has stood near, trembling with eager hope, is overjoyed and smiles for the first time. The buyer then crowns Jeffrey’s happiness by making a promise that he will buy her, if the price isn’t run up too high. And the two lovers step aside and congratulate each other on their good fortune. But Dorcas is not to be sold until the next day, and there are 24 hours of feverish expectation.

Early next morning, Jeffrey is alert, and, hat in hand, encouraged to unusual freedom by the greatness of the stake for which he plays, he addresses every buyer, and of all who will listen he begs the boon of a word to be spoken to his new master to encourage him to buy Dorcas. And all the long morning he speaks in his homely way with all who know him that they will intercede to save his sweetheart from being sold away from him forever. No one has the heart to deny a word of promise and encouragement to the poor fellow, and, joyous with such kindness, his hopes and spirits gradually rise until he feels almost certain that the wish of his heart will be accomplished. And Dorcas, too, is smiling, for is not Jeffrey’s happiness her own?

At last comes the trying moment, and Dorcas steps up on the stand.

But now a most unexpected feature in the drama is for the first time unmasked: Dorcas is not to be sold alone, but with a family of four others. Full of dismay, Jeffrey looks to his master, who shakes his head for, although he might be induced to buy Dorcas alone, he has no use for the rest of the family. Jeffrey reads his doom in his master’s look, and turns away, the tears streaming down his honest face.

So Dorcas is sold, and her toiling life is to be spent in the cotton fields of South Carolina, while Jeffrey goes to the rice plantation of the Great Swamp.

And tomorrow, Jeffrey and Dorcas are to say their tearful farewell, and go their separate ways in life, to meet no more as mortal beings.

In another hour I see Dorcas in the long room, sitting motionless as a statue, her head covered with a shawl. And I see Jeffrey, who goes to his new master, pulls off his hat and says: “I’se very much obliged, Mas’r, to you for tryin’ to help me. I knows you would have done it if you could. Thank you, Mas’r, thank you. But—it’s—very –hard.” And here the poor fellow breaks down entirely and walks away, covering his face with his battered hat, and sobbing like a very child.

He is soon surrounded by a group of his colored friends, who, with an instinctive delicacy most unlooked for, stand quiet, and with uncovered heads, about him.