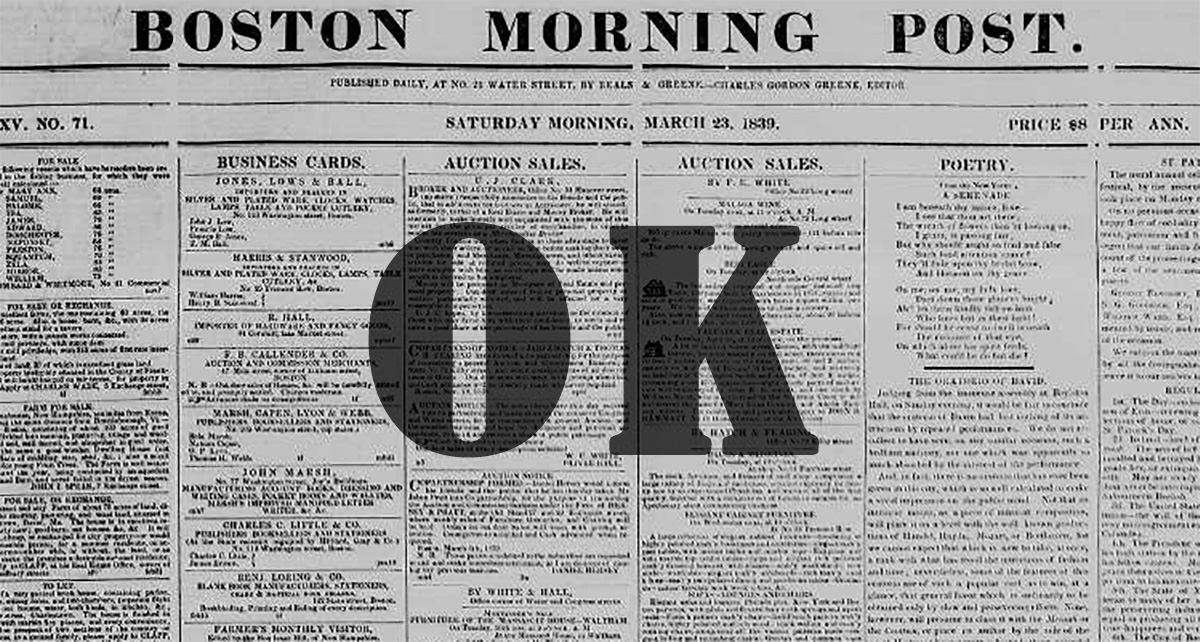

Unlike today’s papers, which strive for broad news coverage and a neutral tone, 19th-century newspapers mostly were written by a publication’s editor, idiosyncratically reflecting his personality. Layouts jumbled fact and opinion—financial news, lurid crime stories, political commentary, short poems, reports on trends, and whatever else the editor felt like covering, often with a personal style that incorporated frivolous abbreviations.

Charles Gordon Greene, editor of the Boston Morning Post, was among the heaviest users of abbreviations, and may have instigated the fad. Abbreviations often appeared in political contexts, as in a June 26, 1838, Post item: “The proceedings were entered on the journal of the House, and reported with great pomposity in the whig papers. S.P. (small potatoes).” Shorthand popped up in non-political articles. “Holman … prepares the m.j.’s [mint juleps] to perfection,” reported a Morning Post story of June 18, 1838. The June 27 edition includes the advice, “All of o.f.m. [our first men] should make frequent pilgrimages to the o.b.s. [Old Boston Stone, an ice cream parlor] in this hot weather.”

Several months into the abbreviations craze, a subspecies of initials started to appear. These represented deliberate misspellings meant to suggest characters speaking in dialect. Popular misspellings converted into abbreviations included o.w. for oll wright (all right), k.y. for know yuse (no use), k.g. for know go (no go), n.s. for `nuff said (enough said), and o.d.v. for oll done vith (all done with). OK fit into this category. The letters stood for oll korrect (all correct).

The first appearance of o.k. occurs in a teasing exchange between Boston Morning Post editor Greene and his counterpart at the Providence, Rhode Island, Daily Journal. The back-and-forth concerns a non-existent organization, the Anti-Bell Ringing Society, on whose fictional farcical doings the Post frequently reported. On March 20, 1839, the Daily Journal editor comments, “Quite an excitement was caused here yesterday by a report in the Boston Post that a deputation from the A.B.R.S. would pass through the city on their way to New York.” However, he continues, “The report proved unfounded.”

The next day Greene, the Post editor, replies, “We said not a word about ‘passing through the city’ of Providence.” He adds that the A.B.R.S. might pass through on its return journey, however. He suggests that the Journal editor should treat Society members to a drink, or in his words, “have the ‘contribution box,’ et ceteras, o.k.—all correct—and cause the corks to fly, like sparks, upward.”

After that debut, OK began to show up frequently in newspaper copy, first in stories on light topics, then in more serious material. A recommendation for a new hotel, the New England House, says, “[the] establishment will be found to be A No. One—that is, O.K.—all correct.” The letters became familiar enough that they began to run without the explanatory “all correct.” An article about Wall Street lingo has a trader saying, “Yes—that’s good—O.K.” A report on the establishment of a benevolent fund for the widow and children of a recently deceased actor includes the sentence, “The net proceeds was upward of $1,200, O.K.” Soon, OK was being read and heard around the country.

OK and similar abbreviations caught on because early 19th-century Americans loved wordplay and absurd linguistic inventions. Coinages like bumfuzzled (confused), exflunctified (worn out), and absquatulate (to leave quickly) were popular, appearing not only in newspapers and magazines but sometimes heard on the floor of Congress—Representative William Wick (Democrat-Indiana) declared in a July 21, 1840, speech, “The administration is … teetotaciously exflunctified.” The 1830s were also the heyday of backwoodsman-turned-politician Davy Crockett, who as a representative from Tennessee was famous for stump speeches that included folksy frontier expressions like bark up the wrong tree and go the whole hog.

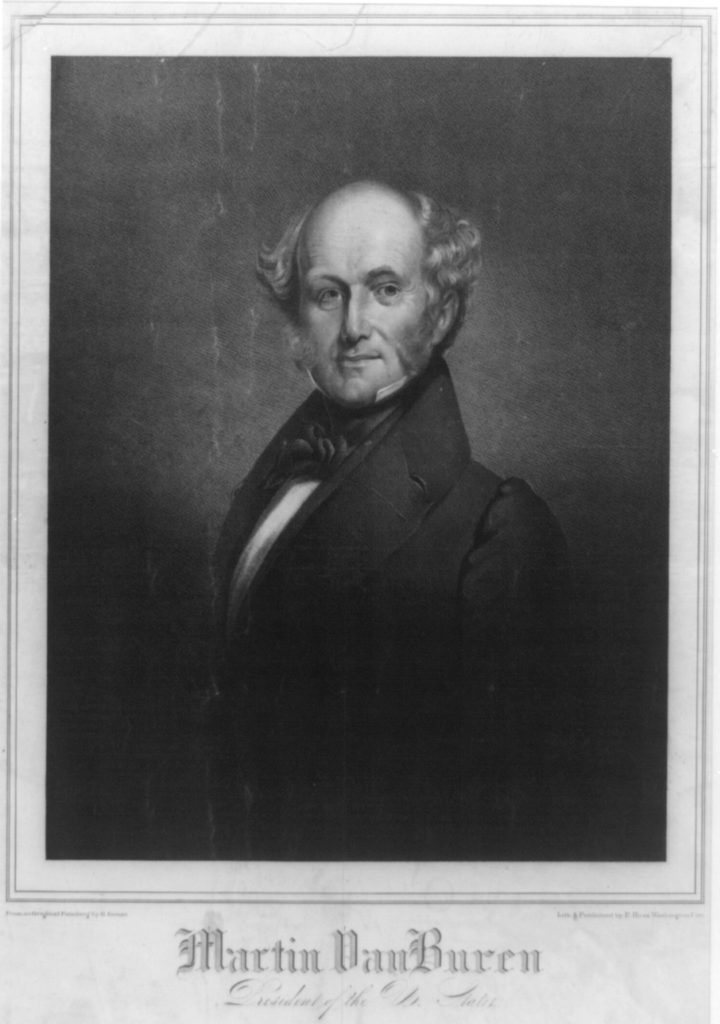

Most abbreviations disappeared by the 1840s as the wordplay fad faded. OK likely would have disappeared as well but for coincidence. The Democratic candidate for president in 1840 was incumbent Martin Van Buren, nicknamed Old Kinderhook, a reference to his birth in Kinderhook, New York. A campaign operative saw an opening for catchy slogans like “Old Kinderhook is O.K.!” Democratic O.K. Clubs were born and Van Buren supporters at rallies waved banners reading “O.K.”

In the end, Old Kinderhook was not OK. He lost to Whig William Henry Harrison. By then, OK was here to stay. Americans embraced this simple way to express agreement or approval. By the mid-1800s, typesetters and letter writers often dropped the periods, and by 1900 the word sometimes was being spelled okay, making it look more like a typical English word. The noun okay, as in “to give the okay,” began appearing in print in the 1840s, while the adjectival form—”an okay time”—was current by the 1870s. The transitive verb “to okay” came in about a decade later, and the 20th century gave us okey-dokey and A-OK. OK is such a handy expression that speakers of languages around the world have adopted it. An expression that started as a joke has turned into one of America’s most popular exports.

_____

Uh huh, yeah, yep

American English has long featured slang terms to express affirmation. One of the earliest is uh huh. British author Frederick Marryat notes in his 1839 Diary in America, “There are two syllables—um, hu—which are very generally used by the Americans as a sort of reply … to express dissent or assent.” The exact origins of uh huh are unclear; some linguists have suggested that it may come from African-American speech.

The language has included several snappy variations on yes for a while. Yessirree and yessirree-bob debuted in print in the 1840s, you bet had achieved currency by 1866, and yep was in use by 1891—along with nope. Yeah appeared on the scene at the beginning of the 20th century.

The OK of today

Several social media abbreviations have made it into the Oxford English Dictionary, suggesting that, like OK, they might permanently join the vocabulary. These include lol (laughing out loud); omg (omigod); imho (in my humble opinion); btw (by the way); and tmi (too much information). Most were being mentioned in print sources such as magazines by the early 1980s.