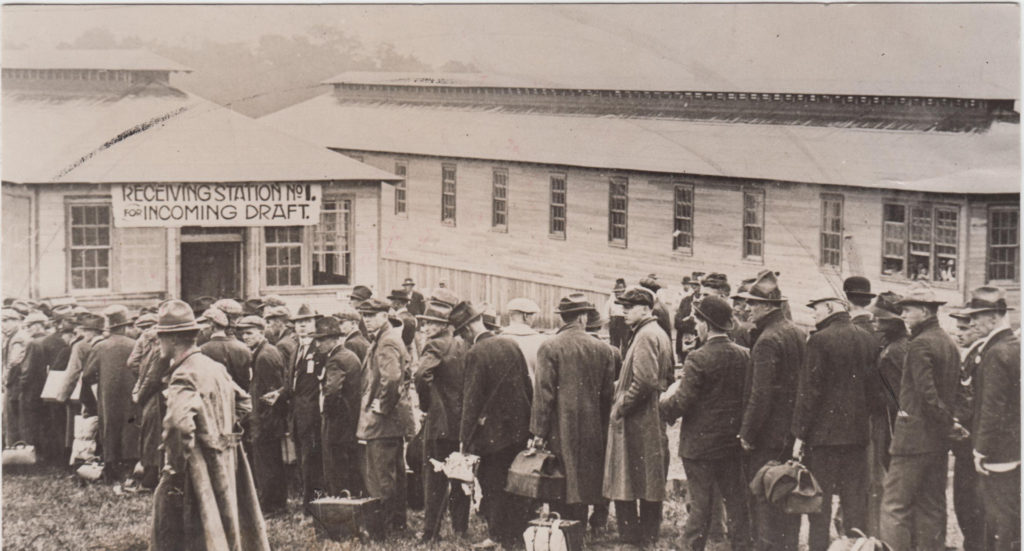

For many mid-20th century Americans, October 16, 1940, was and is R-Day—the date on which all men between ages 21 and 35 were required to register for the draft. As long lines formed, President Franklin Roosevelt addressed the nation on radio. “On this day, more than 16 million young Americans are reviving the 300-year-old American custom of the muster,” FDR said. “On this day, we Americans proclaim the vitality of our history, the singleness of our will and the unity of our nation.”

The District of Columbia opened 47 registration centers to accommodate the 113,371 men who lined up to register in a cold rain. Almost half a million registered in Chicago. The level of cooperation achieved by a nation still split between isolation and intervention was remarkable. Newspapers set up special bureaus of draft information to answer questions about registration, and radio stations made sure their listeners knew how and where to register.

The registration form itself was simple, with 12 boxes to be filled in by examiners who asked a dozen basic questions. An examiner then eyeballed each registrants to determine whether his build was slender, medium or stout. In characterizing race, examiners had five choices: White, Negro, Oriental, Indian, and Filipino.

A wallet-size card handed back to the registrant contained basic information, including date of birth. This document was proof that the signer had registered, and he was advised to keep it with him at all times. Known immediately as the “draft card,” it came into immediate use in verifying age when buying alcoholic beverages. If you were not 21—the legal drinking age in many states and lesser jurisdictions—you did not have a card and could not be served.

One great surprise arising from enactment of the Selective Service law and the events of registration day was a seeming transformation of young college students and graduates from pacifism and isolationism to intervention and a willingness to register for the draft. Smoothly and without incident, some 4,700 students and faculty members at Harvard University registered for military service on R-Day. One overarching factor may have been awareness of the devastation engulfing Europe and the British Isles.

Much coverage greeted the participation of actors and athletes. On location in Big Bear Lake, California, John Wayne registered. In Hollywood and Beverly Hills, a host of younger stars, including Henry Fonda, Don Ameche, Lon Cheney, and Robert Taylor lined up. In Chicago, heavyweight champion Joe Louis, 26, appeared at a segregated registration station, accompanied by his brother and manager. He enrolled under his given name—Joseph Louis Barrow—and the following day an Associated Press photo of the champ ran in newspapers throughout the country captioned, “He’s a fighter for you, Uncle Sam.”

William McChesney Martin Jr., president of the New York Stock Exchange, spent more than six hours trying to find his assigned registration station. Three Rockefellers proudly stood in line, as did the student sons of Ambassador Joseph Kennedy and two of FDR’s sons.

The actual draft began ritualistically at the Departmental Auditorium on Constitution Avenue NW in Washington, DC, on October 29, 1940. “This is a most solemn ceremony,” President Roosevelt intoned to open the proceedings. “It is accompanied by no fanfare—no blowing of bugles or beating of drums. There should be none.’” Despite Roosevelt’s claim, the event displayed, as one historian put it, all the “panache of a Hollywood award ceremony.” As the commander-in-chief was speaking before a large crowd, warplanes flew by outside.

Celluloid capsules holding the lottery numbers were escorted to the auditorium by 500 veterans of World War I. The blue-tinted capsules were dumped into a 10-gallon fishbowl and stirred with a wooden spoon made from a beam from Independence Hall in Philadelphia. The fishbowl, last used for the draft in 1919, had come from Philadelphia with a full military escort.

Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, blindfolded with a strip of yellow linen cut from the fabric used to upholster the chair used in the signing of the Declaration of Independence, drew the first capsule. He handed it to the president, who announced the number: 158.

At this, a woman in the audience screamed loud enough to be heard over the CBS radio network. Washingtonian Mildred Bell explained later that her son Robert held the number 158. Across the country, 6,175 men who held that number now knew they were required to report immediately for a physical. At the end of the CBS broadcast, reporter Robert Trout concluded his report by telling listeners his own lottery number.

After the initial numbers were drawn, local boards sent a questionnaire to each man affected to determine his eligibility. Recipients had five days to answer and return the eight pages of questions. Their responses would be regarded as confidential, to seen only by their draft boards. Based on registrants’ sworn answers, the boards shunted candidates into four categories. Class 1 was men available for induction into the Armed Forces. Class 2 was men deferred from induction because their civilian jobs were important to the national good. Men in Class 3 were deferred because they had dependents relying on them. Class 4 encompassed governors, sitting judges, and others whose induction was prohibited by law. Men in sub-class 4-F were deemed unfit for service for reasons of physical or mental health or because they were in prison, a mental hospital, or otherwise removed from society. Men classified 1-A—fit for service—were in line to be called up and sent to an induction center. The system ensured that a skilled worker in a key industry would be called up last. Such men would do ten times as much good on the job as in uniform, a member of the Selective Service committee told the Washington Post.

Using lists compiled by governors and state adjutants general, the War Department already had selected draft boards and personnel to staff them. Attached to each board was an appeals board, a physical examination board, and a medical appeals board. Boards had a simple set of parameters. A man had to be between 21 and 45, at least 5’ tall and no taller than 6’6”, weigh at least 105 lbs., have vision correctable with glasses, and have at least half his teeth. He had to be able to read and write, and not have been convicted of a crime. Foreigners who had taken out initial papers toward obtaining citizenship were eligible; those who had not were ineligible. Members of the Communist Party and the German American Bund were on the same footing as members of any political group.

Draft boards were to screen out men draft officials referred to as “young bums.” At an October 22 press conference, Selective Service and War Department officials urged draft boards to resist the temptation to use conscription to rid their communities of fellows seen as ne’er-do-wells and troublemakers. They challenged the commonplace wisdom that the Army made good men of bad boys. Instead of military discipline squaring troubled individuals’ shoulders, the word went out, such men often resisted discipline and became drunks, hypochondriacs, and mental cases. During World War I, 88,000 inductees—described as burdened by mental and nervous instability—had broken down under the strains of military life and afterwards required hospitalization, costing taxpayers $33,000 per man, officials said.

Conscientious objectors and war resisters were rare, and most but not all registered, as the law demanded. On November 14 in a New York City courtroom, eight theological students who had refused to register reiterated that resistance, claiming they simply were adhering to the teachings of Jesus Christ. Unwilling to recant when a judge gave them a chance to do so, the eight were sentenced to a year and a day in a federal penitentiary. The trial signaled the government’s position that refusal to take part in the system was a felony.

Opposition to the war as a matter of conscience or faith became an issue. Over several months, authorities imprisoned 5,000 to 6,000 men on grounds that they had failed to register or to agree serve the nation in some alternate way. These resisters were mostly Jehovah’s Witnesses reprising the stance members of that sect had taken during World War I. Jehovah’s Witnesses also refused military service in Adolf Hitler’s Germany; more than 10,000 died in Nazi concentration camps.

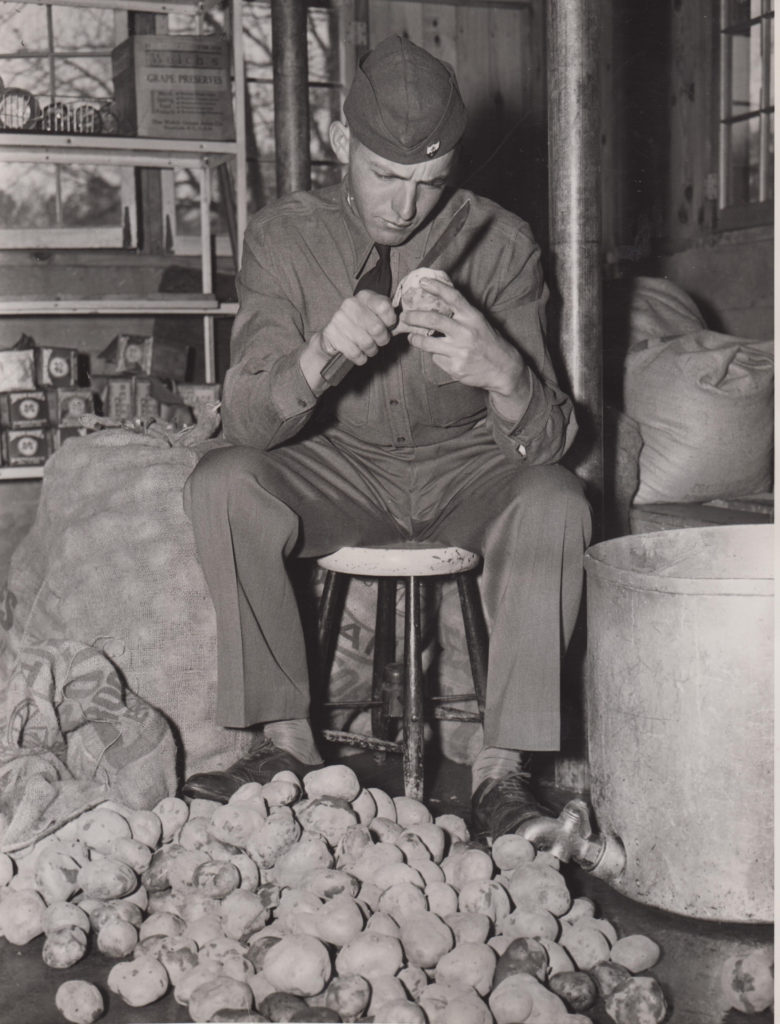

After R-Day, a thought occurring to many and promoted by the government was the sunny potential of a year in the Army, which would be assigning and training volunteers and draftees specialties ranging from cook to automobile mechanic. “When the average draftee leaves the service today he will be far better equipped to earn a living than he was when he went in,” wrote the popular Sunday supplement This Week.

Men inclined to such thinking, many of them out of work and cleared for military service, were invited to volunteer on induction day, the idea being that their entry into the ranks would lessen the need for conscription and soften the draft’s impact. In the early weeks, 71,000 “volunteer draftees,” as they were known, asked draft boards to put their names at the top of the list, reducing from 30,000 to 19,700 the number of draftees called by December 1. In some areas, so many men volunteered that during 1940 few actually were drafted. Forty percent of volunteer draftees were unemployed, evidence that the Depression was still a fact of life.

Once volunteers had undergone physicals, draft boards called all 6,175 holders of number 158 to be considered for service. Men holding subsequent lottery numbers were called in order and received an “order to report for induction.” That letter named the branch of service a man was being called to and gave the date, time, and place to complete his paperwork and undergo a final physical.

On Monday, November 18, two months and two days after President Roosevelt signed the nation’s first peacetime conscription bill, the first group of 984 volunteer draftees reported at 9 a.m. to induction centers in the six New England states, immediately undergoing a second physical. Each affected induction board’s staff included a neuropsychiatrist, three internists, an eye specialist, an orthopedic surgeon, one general surgeon, a nose and throat specialist, a clinical pathologist, and a dentist.

Induction was simple, but not subtle—a fast-moving assembly line that in an hour could process about 25 men. Most of the physical took place unclothed. Stark naked men bore numbers written on placards hung around their necks or on the backs of their hands. This gantlet included the psychiatric exam, which led some examiners to conclude that that nakedness made men more likely to shed their defenses. Nudity made some men nervous, often rendering inductees unable to urinate into a specimen bottle on demand.

At the end of the line, men learned if they had been approved; those who failed were sent home. Those approved were fingerprinted, assigned a serial number, and sworn in, then sent to a reception center to be given uniforms, vaccinated, and receive basic military training before being sent to regular units. As time passed the system dropped the unsettling routine of waking up at home and sleeping that night at a military facility, and instead swore in inductees and gave them two weeks to get their affairs in order before being processed into the army.

The first man inducted was from Boston. John Edward Lawton, 21, an unemployed plumber’s helper, secured that status when the three fellow volunteer draftees ahead of him failed their physicals. It startled doctors at that induction center to find that volunteers given a chance to reveal disabilities on their questionnaires and put through one physical were failing the final physical. The next morning’s Boston Herald headlined the phenomenon: “20 P.C. OF DRAFTEES SENT HOME.”

Officials had assumed that no more than two percent of men called up or volunteering in the first days of the draft would have physical deficiencies sufficient to disqualify them. They were wrong. An early report from New York City revealed that a quarter of men called to induction centers on a given day were found unfit for service. The Dallas Morning News reported that on a day in November, a third of men called were unfit. The most frequent disqualifiers were a shortage of teeth and poor vision, neither condition hard to diagnose. Around Baltimore, Maryland, hernias caused most rejections.

The lingering effects of the Depression quickly made themselves known. That first year, nearly half the men drafted were sent home. More than 100,000 were rejected for illiteracy. Punctured ear drums that made a man susceptible to poison gas even while masked got many men classified 4-F. Of the first million draftees, more than 30,000 had untreated, active cases of syphilis, gonorrhea, and other venereal diseases that disqualified them for service.

Most disturbing was the number of men displaying the impact of poor nutrition. Of the first million men that draft boards screened in 1940, reviewers rejected at least 130,000 for severe disabilities relating to poor diet. This finding led to a government decision to spike staple food products with vitamins and minerals. Thiamin, niacin, iron, and eventually riboflavin became ingredients in enriched bread and breakfast cereals. Federal food fortification was not new—since the 1920s, salt producers had been dosing their product with iodine to prevent goiter—but the draft rejection rate for the malnourished imbued the practice with new urgency.

Race intruded. When Connecticut attempted to send two Negro volunteers into service, an order came down from the First Corps headquarters in Boston that these men could not be accepted. Connecticut Governor Raymond Baldwin then threatened to take the matter up with the War Department in Washington, and the officers in Boston backed off. Southern states in the Fourth Corps region announced the number of men going into uniform in the first call by race—Alabama planned to send 313 whites and 134 Negroes.

Men did try to avoid induction, feigning ailments or having dentists pull perfectly good teeth. Others, as if trying to prove their manhood or patriotism, did their best to hide deficiencies. Draft board physicians learned to spot epileptics trying to conceal that condition by studying lips and tongues for scars left by seizures. Virtually every draft board had stories of men who, having been rejected, demanded a repeat physical, memorized the eye chart, or enlisted in a different service, finding their way into uniform by any means necessary.

John Fitzgerald Kennedy, who had graduated from Harvard in June 1940, registered at Stanford University that September, under a “permit to attend,” which allowed him to audit classes of his own choice without credit. He was one of 22 Stanford students among the first wave of prospective draftees assigned deferments until the end of the academic year. In early 1941, as the European situation deteriorated, Kennedy, 24, decided that rather than wait until his deferment ran out, he would seek a commission by enlisting in the army but was rejected as medically unfit. He applied to the Navy; again, he was turned down for medical reasons. In September 1941, with a boost from a highly placed Navy officer who was a former colleague of his father and a letter from a Boston doctor declaring him fit for service, Kennedy was accepted into the U.S. Navy.

Actor Jimmy Stewart was at the height of his fame in late 1940 when he was drafted. He was 6’3” but only weighed 138 lbs., causing Army doctors to reject him as underweight. Stewart, a licensed pilot who wanted to serve in the Army Air Corps, sought help. MGM muscleman and trainer Don Loomis put the string bean star on a workout and diet regimen. Reexamined on March 21, 1941, he was deemed 1-A, immediately sworn in as a private, and sent to Fort MacArthur, California. “I’m sure tickled I got in,” Stewart told reporters, who noted that his salary had gone from $12,000 a month to $21 a month.

As 1940 was ending, many draftees now in uniform celebrated the New Year with the understanding that their fellow Americans believed the Army and local draft boards were off to a good—and equitable—start. A Gallup poll counted 92 percent of respondents as saying that the draft was being handled fairly; 91 percent said the Army was taking good care of draftees. An overwhelming 89 percent thought the draft wise and a “good thing,” given circumstances in Europe. By New Year’s 1941, the Selective Service mechanism had inducted 18,933 men—compared to what was coming, a drop in the bucket, but the system was up and working.

Excerpted from The Rise of the G.I. Army 1940-1945: The Forgotten Story of How America Forged a Powerful Army Before Pearl Harbor © 2020 by Paul Dickson (pauldicksonbooks.com). Published in 2020 by Grove Atlantic Inc., groveatlantic.com/book/the-rise-of-the-gi-army-1940-1941/, $30.