Norton I, Emperor of the United States, was San Francisco’s favorite benign fraudster

Dressed, as always, in his blue uniform and a hat crowned with peacock feathers, ceremonial sword dangling from his belt, Norton I, Emperor of the United States, strode through a cold rain, heading to a lecture at San Francisco’s Academy of Natural Sciences. It was January 8, 1880. A few steps from his destination, Norton staggered, then fell to the sidewalk. By the time police arrived, he was dead.

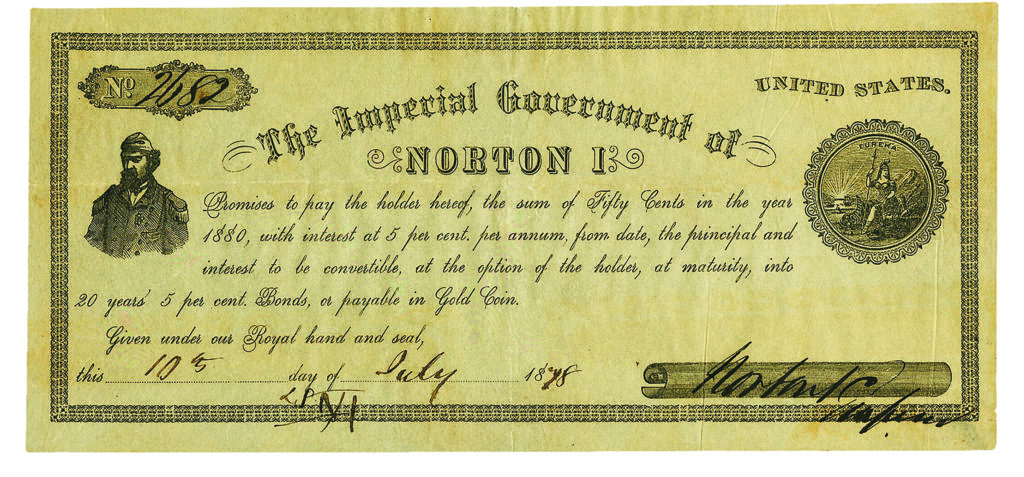

Reporters who’d been covering the Emperor for decades hustled to the morgue and jotted notes about the contents of his pockets—a few silver coins, a French franc, a gold piece worth $2.50 and a pile of the “Imperial Government” bonds Norton sold for 50 cents each.

“Le Roi Est Mort,” read the headline in the San Francisco Chronicle, which reported that 10,000 people gathered to view the Emperor’s royal remains: “The visitors included all classes from the capitalist to the pauper, the clergyman and the pickpocket…” In Seattle, Denver, Philadelphia, and New York, newspapers ran obituaries. “Emperor Norton Gives Up the Ghost,” the Cincinnati Enquirer headlined. “An Emperor Without Enemies, A King Without a Kingdom, Gone to Kingdom Come.”

Joshua Abraham Norton was not born to the purple. He was a self-made—or self-proclaimed—emperor. Born in England in 1818, he emigrated with his family to South Africa, where the Nortons became wealthy merchants. In 1849, with his parents dead and a gold rush beckoning, Norton took his inheritance and sailed to San Francisco.

Smart enough and rich enough to avoid digging for gold, Norton settled in town, buying real estate, starting a cigar factory and a rice mill, and dealing in wholesale commodities. By 1852, he was richer, given to amusing business cronies with monologues urging that America ditch democracy and become a monarchy. “If I were Emperor of the United States,” he said, “you would see great changes effected.”

Friends laughed. They thought he was kidding.

In 1852, a famine caused China to ban export of rice, causing rice prices in San Francisco to skyrocket. When a shipload of Peruvian rice docked, Norton mortgaged his land holdings and bought all 200,000 lbs., at 12.5 cents per. Assuming he’d cornered the San Francisco rice trade, he anticipated huge profits. But more rice arrived, glutting the market. The price plummeted to 3 cents. Norton went broke and lost the real estate he’d mortgaged. Ruined, he declared bankruptcy in 1855 and disappeared, living in flophouses, avoiding his rich pals.

On September 17, 1859, Norton reemerged, strolling into the Evening Bulletin office, demanding that the newspaper publish his handwritten proclamation: “At the peremptory request of a large majority of the citizens of these United States, I, Joshua Norton, formerly of Algoa Bay, Cape of Good Hope, and now for the past nine years and ten months of San Francisco, California, declare and proclaim myself Emperor of these United States…”

He signed his decree “Norton I, Emperor of the United States.” An impish editor published it under the headline, “Have We An Emperor Among Us?”

The notion of having their own Emperor amused San Franciscans, so the Bulletin published more Norton proclamations, now couched in the royal we. “We do hereby abolish Congress,” he wrote in his second decree. Soon, he was deep-sixing the rest of the government: “We, Norton I, by the Grace of God Emperor of the 33 States and the multitude of Territories of the United States of North America, do hereby dissolve the Republic of the United States…” He replaced that republic with “an Absolute Monarchy,” headed, of course, by himself.

Norton’s proclamations proved so popular that when he failed to add to his oeuvre, newspapers sometimes drafted fakes. He became San Francisco’s most famous eccentric, strolling the streets blue-uniformed and in a plumed hat, chatting with his royal subjects, who bowed and called him “Your Majesty.” Theaters reserved seats for him on opening nights. The Central Pacific Railroad gave him a free pass. Shops sold Emperor Norton postcards, dolls, and cigars. A local theater featured “Norton the First,” a musical that, one reviewer wrote, caused “irrepressible laughter.”

Somehow, the Emperor neglected to collect his cut of profits from the play, the souvenirs and the cigars. But the man who’d attempted to corner the rice market hadn’t lost his entrepreneurial outlook. He supported himself by selling official-looking “bonds” issued by “The Imperial Government of Norton I.” Most cost 50 cents and featured the Emperor’s picture and his promise to repay the half-dollar, plus 7 percent interest, in 1880. Norton sold enough bonds to be able to afford restaurant meals and pay his 50-cent daily rent at Eureka Lodgings, a fleabag joint on Commercial Street.

In 1867, an overzealous cop arrested Norton as a “lunatic” requiring “involuntary treatment of a mental disorder.” The newspapers howled in protest: “The kindly Monarch of Montgomery Street is less a lunatic than those who engineered these trumped-up charges.” The Emperor was quickly released.

Was he insane? Did he really believe himself to be an emperor? Or was he a proto-performance artist earning a living by parodying royalty? Two famous San Francisco reporters reached conflicting conclusions. Ambrose Bierce, the renowned cynic, saw Norton as a fraud who had found a way to live “without physical or mental toil.”

Mark Twain disagreed: “Although nobody else believed he was an emperor, he believed it.” Norton’s most assiduous biographer, William Drury, agreed with Twain, concluding that the Emperor was schizophrenic.

Norton might have been crazy but he wasn’t stupid. He spent afternoons in the Mechanics Library, studying technical publications, and he designed a railroad switch that was, alas, never constructed. An 1872 proclamation urged the construction of a bridge between San Francisco and Oakland and said exactly where. Six decades later, the Bay Bridge was built on the route Norton suggested.

And the Emperor never lost his talent for financial finagling. As 1879 was ending, it came to him that he’d floated hundreds of bonds promising a payoff in 1880. Of course, he couldn’t keep that promise, so he did what sketchy bond sellers do: He offered to replace the old bonds with new bonds, payable in 1890.

A week later, felled by a stroke, he dropped dead on a rain-soaked sidewalk. Cronies funded an elegant rosewood casket and thousands lined the streets to watch horses haul Norton to his grave.

Today, the Emperor’s original 50-cent bonds are said to be worth $15,000 apiece. His name and image adorn T-shirts, mugs, bottles of Emperor Norton Absinthe, and a San Francisco bar, Emperor Norton’s Boozeland. Tourists pay $30 for a three-hour walking tour of San Francisco led by a guide in full Norton regalia, impersonating the man who impersonated an Emperor. Have any “real” emperors inspired so many smiles 140 years after their demises?

This American Schemers column appeared in the August 2020 issue of American History.