When Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager landed at California’s Edwards Air Force Base in the Rutan Voyager on December 23, 1986, they completed a historic flight that tested the limits of aircraft design and human endurance. The pair had left Edwards on December 14, having spent nine days and three minutes in the air during their nonstop, unrefueled flight around the world—the first of its kind. Along the way they nearly came to grief several times, as they grappled with exhaustion, mechanical problems, severe weather and even political considerations.

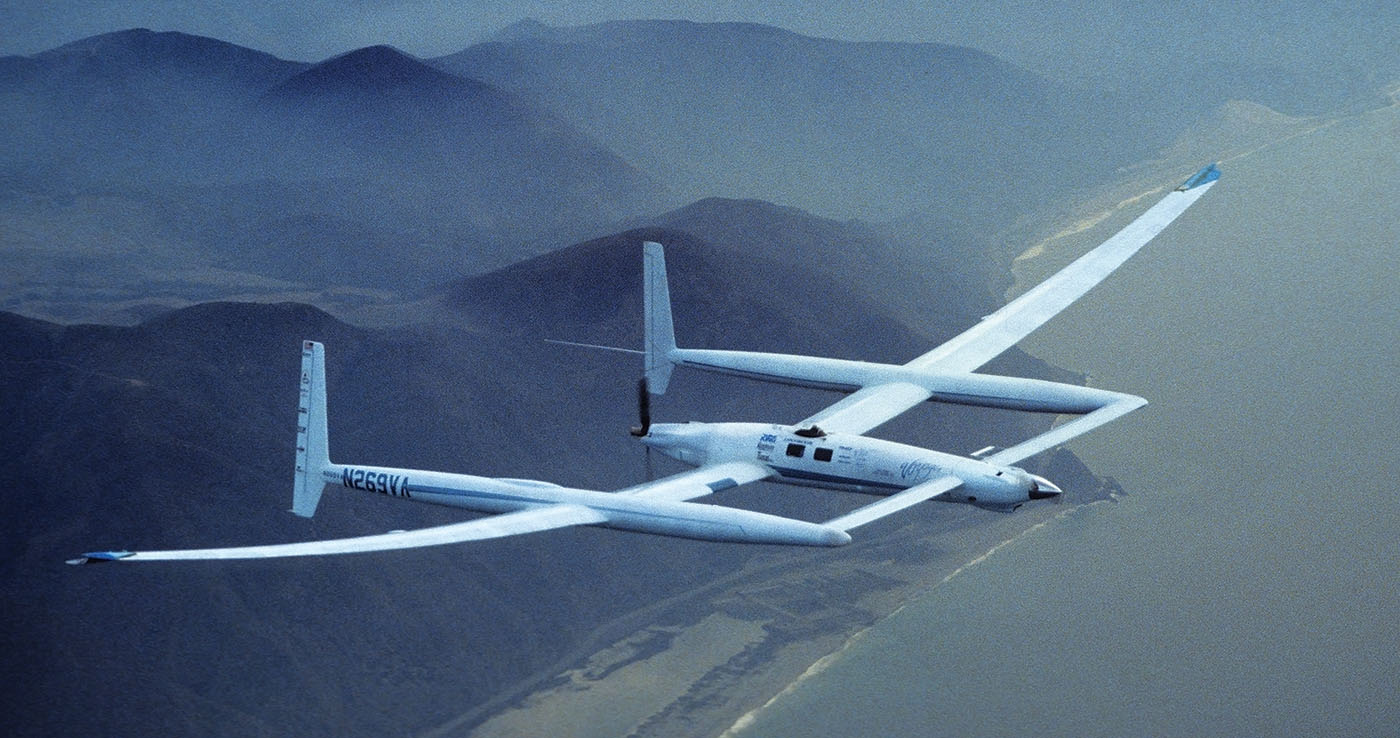

Dick’s brother Burt had first sketched Voyager’s design on a paper napkin at a Mojave, Calif., restaurant in 1981. Such an airplane—essentially a flying fuel tank—had been thought impossible.

The challenges Burt Rutan faced were daunting. He had to balance the necessary fuel capacity with the need for increased lift to overcome the fuel weight and higher induced drag. That required additional wing area, which in turn increased drag, compelling Rutan to use a high-aspect-ratio wing—long span and narrow chord—and enormously complicating the structural design.

The wing he needed could not be built without the aid of carbon composites, which boasted a strength-to-weight ratio seven times greater than that of steel. At the time Voyager was the largest composite aircraft ever to fly.

Construction of Voyager in the Rutan hangar at Mojave took two years of day and night work by a team of dedicated volunteers. Over the next three years, the airplane made 67 test flights, revealing serious operational issues. During a three-day flight, Dick and Jeana found the interior noise level generated by the tandem-mounted, push-pull engines almost unendurable, threatening permanent hearing loss, so the team added active-noise-suppression headsets. On another flight the electric propeller pitch-control motor on the front engine shorted out. Before it could be shut down, the engine shook off its mounts and the propeller departed. The only thing that saved Voyager and its crew was a flexible strap holding the engine to the fuselage.

Heading to Oshkosh, Wisc., in 1984 for the Experimental Aircraft Association fly-in, Voyager encountered a rainstorm that reduced lift from its wide canard to the point where the airplane kept losing altitude no matter what Dick tried. “I had a horrible feeling in the pit of my stomach,” he said, “as the airplane was coming down, and I couldn’t stop it.” Voyager emerged from the storm and regained lift just in time to avoid the terrain ahead. To fix the problem, team members installed tiny vortex generators on the canard that smoothed the airflow. Solving these and other issues occupied the next two years.

Preparations for the around-the-world flight involved numerous additional tasks, such as securing the many overflight clearances required, studying regional weather patterns and setting up global communications relays. The support team included recognized experts in such fields as meteorology, communications, instrumentation and control engineering.

Burt Rutan’s design was precisely tailored to the mission, but Dick and Jeana learned that with a high fuel load Voyager was barely flyable. The long-span, unusually flexible wings went from a pronounced droop at the start of takeoff to a hawk-like upward curve as they generated lift. The transition from takeoff to climb had to be flown with knife-edge accuracy to avoid dangerous wing oscillations. Designer and pilots knew Voyager was fundamentally unsafe. “This thing flies like a turkey vulture,” Dick said.

In order to save weight, the airplane’s fuel system—16 individual tanks and two pumps (one per side) transferring fuel into a single central tank feeding both the forward and rear engines—was not equipped with automatic valves or individual fuel pumps. Hence keeping Voyager within center-of-gravity limits was a continuous burden, mostly on Jeana, who kept a meticulous fuel transfer record.

To reach its maximum range, Voyager had to maintain a best lift-over-drag attitude, with a specific constant angle of attack for each speed. Burt’s carefully planned vertical profile specified the speed for each successive stage as fuel weight diminished. On a flight lasting over a week, that task required an autopilot.

On the morning of December 14, Voyager was loaded with 7,011.5 pounds of fuel, 15 percent more than on its heaviest previous flight. The aircraft’s gross takeoff weight was 9,694.5 pounds, supported by an airframe that weighed just 939 pounds. The landing gear was designed to handle that one-time load on takeoff, which would be made from Edwards’ 15,000-foot runway.

Team members pumped air into the gear struts to provide a bit more clearance for Voyager’s drooping wings, then added more fuel to the forward tanks. Those actions slightly twisted the wings forward and down, inadvertently setting the stage for a potential disaster. In anticipation of the extra weight, the tires were inflated to a pressure of 3,200 psi, almost twice the rated maximum.

The halfway point on the runway, at 7,500 feet, was the agreed abort point in the event Voyager hadn’t reached the required 83 knots to begin rotation. As Voyager lumbered down the runway just after 8 a.m., it was still four knots short when it reached that point. Over the radio, Burt yelled, “Dick, pull the stick back, dammit!” But knowing he didn’t have adequate speed for liftoff and refusing to abort, Dick left the throttles wide open, staking their lives on that crucial decision. “The airplane was accelerating smoothly,” he later said, “and the end of the runway was still a mile and a half ahead.”

Dick was unaware that the extra fuel weight had caused the wingtips to scrape the runway, and that the outboard wing sections were now generating negative lift. Voyager was at the 11,000-foot point when it reached 83 knots, but still Dick didn’t rotate; a premature attempt at liftoff might fracture the wings between the inner sections generating lift and the outer sections still under downward pressure from negative lift. He held the airplane on the runway until Jeana called “87 knots,” and only then began to ease back on the stick as the assembled crowd screamed “Pull up, pull up!” Voyager finally lifted off 14,200 feet down the runway, a mere 800 feet from the end. “One hundred knots,” Jeana called out, as Voyager reached 100 feet altitude. “We needed the extra lift from ground effect—within our 110-foot wingspan—which I used to boost our airspeed to the climb target,” Dick explained.

The scraped wingtips were damaged to the point where they were soon shed, leaving tattered foam and loose wires exposed at the ends. How close was the wingtip damage to the fuel tanks? Could a leak have been started? Could the exposed wires cause a short during a storm? Nobody knew, so Voyager simply flew westward. Early in the flight, the overburdened airplane burned fuel so fast that a pound of fuel yielded less than two miles of flight distance.

One hour into the flight, Voyager was 7,400 feet above the Pacific. The aircraft’s inherent instability would continue to pose a threat even after it was safe to turn on the autopilot. Dick had to be at the controls in case significant oscillations began that the autopilot couldn’t immediately correct. Although Jeana had a few hundred hours of flying experience, she hadn’t yet learned how to prevent those dangerous oscillations, which could break up the airplane while it was so fuel-heavy. Jeana looked out the cockpit window and exclaimed, “See the wings! They’re almost flapping.”

For the next three days, Dick stayed at the controls. His lack of adequate sleep set the stage for new dangers ahead. Jeana’s neck grew stiff as she lay on her side watching the instruments while Dick catnapped. “He needed the rest,” she said, “so I had to monitor what the airplane was doing, and reach around him to make any adjustments.”

After passing Hawaii, they entered the Intertropical Convergence Zone, with high-altitude westerly winds and low-altitude easterly winds. Voyager stayed at 7,500 feet, along the five-degree north parallel, an area of frequent storm activity. As they approached Guam, the weather guru at Mission Control in Mojave, Len Snellman, warned the crew about a large typhoon just to the southeast. Voyager was able to pick up some tailwind from the typhoon’s counterclockwise circulation by skirting it on the north side. That tailwind would provide an important gain in fuel savings.

From about mid-Pacific all the way to Africa, the crew and Mission Control became increasingly concerned about the rate of fuel consumption indicated by Jeana’s log. For reasons unknown, possibly leaks from the wingtip damage, there might not be enough fuel to complete the mission. They began to actively consider possible emergency landing sites. Dick remembered “a sinking feeling in my stomach; I wanted to cry. We were looking at failure.”

Overflying Sri Lanka, with its 10,000-foot runway, Dick felt so tired he could hardly resist the temptation to land. But his mother’s words, “If you can dream it, you can do it,” ran through his mind, and he knew Jeana wanted to fly on, so they did. Later, Jeana discovered a reverse flow of fuel from the feeder tank back to the selected fuel tank. Dick guessed the amount was insufficient to drain the feeder tank and stop the engine, but there was no way to know for sure.

Voyager approached the African coast well south of Somalia (for which they had no overflight clearance) on a moonless dark night. Jeana was at the controls while Dick slept in the rear compartment. Fuel was still a concern, so she ran the rear engine lean. Their radar revealed a storm ahead, just south of their course. Jeana awakened Dick, and as he got into the cockpit they were at the edge of the storm. They were through the turbulence in a few minutes, about to start across a continent with few airfields and a sky full of storm clouds.

Voyager was over western Kenya, on its planned course, heading for Lake Victoria and cumulus buildups, with mountainous terrain beyond. They were five hours late for an inflight rendezvous with Doug Shane, who had flown by airline to Kenya and rented a Beech Baron in order to observe Voyager up close to see if the wingtip damage had caused fuel leaks requiring a mission abort. Voyager already was climbing to avoid Mt. Kenya and other peaks ahead over 17,000 feet. Shane was nearing the Baron’s ceiling, with only a few minutes to approach Voyager and inspect for fuel leaks in the early morning light. “No ugly blue streaks,” he called. Relieved to know Voyager was not leaking fuel, they climbed to 20,500 feet to clear the mountains ahead.

Dehydration and equally insidious hypoxia threatened their survival. Neither Dick nor Jeana had managed to drink enough fluid to replenish their losses flying so high. Nor were they breathing 100-percent oxygen, required for that altitude, because earlier Dick had dialed it back to conserve their supply. Dick could see Jeana’s reflection in the radar screen; she was curled up like a cat, sleeping soundly—too soundly. Dick called, “Jeana, wake up! Wake up!” while reaching back to shake her. “What, what?” she finally responded, then quickly fell back asleep. Soon after, Dick said, “Jeana, look at this,” shaking her awake again. “Look at the instrument panel! It’s bulging out; it may explode!” “It’s o.k., Dick,” she reassured him, “you’re just tired. I’ll take care of it.” As Voyager descended to 14,000 feet, Dick’s hallucinations stopped. Jeana squeezed past him and took the controls. Her head was pounding with a migraine headache. “My stomach was churning, I started vomiting into my little throw-up bag,” she said. “I just kept flying; Dick was in worse shape.”

Night overtook them as Jeana let Dick sleep longer than planned because of his extreme fatigue. After he was back at the controls, Dick realized they were very late for the course change to avoid Mt. Cameroon. “Why didn’t you wake me?” he yelled. “There’s a mountain out there and we almost ran into it.” “So, why didn’t you remind me of it?” Jeana replied.

Clearing Africa, the two fliers experienced an overwhelming sense of relief. Looking at Dick, “I saw big tears rolling down his cheeks,” Jeana remembered. “I reached over his shoulder and gave him a hug.”

On crossing the South Atlantic, things took a turn for the worse. As Voyager approached the coast of Brazil, Mission Control lacked weather satellite data and could not provide adequate guidance for the location. With bad weather ahead, Dick was forced to thread his way through an area of dense thunderstorms, in the dark. Their radar showed storm cells close ahead, at right, left and center. Turbulence tossed Voyager like a cork, and a cell swallowed the aircraft. One wing was forced high and the other low as the aircraft quickly went into a 90-degree bank. Voyager was about to go inverted. “Well babe, this is it, I think we’ve bought the farm this time,” Dick said. “Look at the attitude indicator. We ain’t gonna make it.” Jeana stayed quiet.

The cell ejected Voyager, but it was still far over on its side—an attitude out of a bad dream. Dick knew the only way to recover was to unload the G-force on the wings and regain airspeed, and only after that gently roll back level while ensuring airspeed didn’t build too rapidly to recover. “We never banked Voyager over 20 degrees before,” Dick noted. “I’d rather go back across Africa than tangle with one of these storms again.” Mission Control was soon getting better weather satellite coverage and helping the crew find the safest way through the remaining storm cells.

After the adrenaline wore off, Dick desperately needed rest. Jeana took over, dodging cumulus clouds for the next three hours. The airplane had by this time consumed most of its fuel and was lighter, so fuel economy increased, allowing them to shut down the forward engine. Over the Caribbean, north of Venezuela, Voyager’s fuel economy climbed to five miles per pound—30 miles per gallon. Nevertheless, the uncertain fuel situation prompted the crew to run the engine very lean. Mission Control warned of cumulus buildups over Panama, and suggested overflying Costa Rica instead.

Later, heading northwest off the Nicaraguan coast, Voyager aimed for home as dawn broke on the flight’s eighth day. Headwinds slowed its ground speed to 65 knots. Dick flew on as Jeana managed the fuel flow. Suddenly the right side fuel pump went into overspeed and failed. Dick had anticipated such a possibility and arranged a bypass of the feeder tank through the engine’s mechanical pump. Now he made the switch and fuel again flowed. But the sight tube had to be checked constantly, to detect the first bubbles of air in the line.

When the engine coughed a few times, changing tanks brought it back to life. Dick switched to a tank in the canard that he thought had plenty of fuel, but it didn’t and the engine stopped. Voyager had been running at 8,000 feet on the rear engine, to conserve fuel. Now they heard only the wind. Dick lowered the nose, hoping higher airspeed would restart the windmilling engine, to no avail. Without engine power, the mechanical pump couldn’t operate.

Voyager was now down to 5,000 feet. Mike Melvill in Mission Control suggested starting the front engine, but Dick feared that would block the rear engine, with its still windmilling prop, from restarting. They needed both engines to get home. The situation was critical; Voyager was rapidly losing altitude.

Dick and Jeana followed the cold-engine-start checklist. “Elbow flying now,” Dick said, needing both hands for the restart sequence. “Just take it easy, Dick,” Jeana said. “You’re doing fine.” Voyager, heavy on the right side due to the fuel imbalance, continued down. Dick used the avionics backup battery to avoid an instrument-killing current surge from the main battery. Still, the front engine would not start. At 3,500 feet Dick leveled out, allowing the fuel to flow, and the engine finally coughed to life.

Now they had to finish replacing the right-side pump to relieve the imbalance from Voyager’s fuel-heavy right wing. Dick installed the pump while Jeana got the many valves turned correctly. An anxious half-hour passed before enough fuel to get them home flowed slowly into the feeder tank.

Finally Voyager left the ocean behind, and at first light was over California’s San Gabriel Mountains. Chase planes flown by Melvill and Shane joined up while Dick and Jeana kept their focus on precision flying. Voyager appeared over Edwards at 7:32 a.m. Dick did a flyby at 400 feet and a few more with the chase planes. He wanted to do one more flyby, at just 50 feet, but Jeana chimed in, “Dick, time to land, we’re running low on fuel.” Thousands of people were waiting as they carefully landed, taxied to the parking area and shut down the engines that had taken them around the world. When the leftover fuel was drained, little more than 108 pounds (18 gallons) of the original 7,000-plus pounds remained.

Voyager’s world flight remains one of the greatest achievements in aviation history. For their feat, the Rutans, Yeager and the Voyager team were awarded the 1986 Collier Trophy.

Pierre Hartman is a former light-sport pilot who lives in Tehachapi, Calif., 20 miles from Mojave. Further reading: Voyager, by Jeana Yeager and Dick Rutan, with Phil Patton; and Voyager: The World Flight, by Jack Norris.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2019 issue of Aviation History.