Nogales was unbearably hot in the summer of 1918, and tensions simmered between Mexican citizens on the Sonoran side of the border and their American neighbors on the Arizona side. Locals collectively referred to the divided communities as Ambos (or “both”) Nogales. Nothing more than a dusty road—International Street/Calle Internacional—separated the respective halves of the border town, but prejudices, injustice and bitterness deeply divided its residents. The situation was about to reach a flash point.

In mid-August U.S. Army intelligence handed Lt. Col. Frederick J. Herman a mysterious letter written by a man claiming to have been a major in the Mexican revolutionary forces of Gen. Francisco “Pancho” Villa. Herman, who commanded the black “buffalo soldiers” of the 10th U.S. Cavalry Regiment, also served as the military subdistrict commander in Nogales. He read the letter with deep concern, as its writer warned German agents were organizing and providing weapons to Mexicans for an assault on the Arizona border town later that month.

The message was consistent with intelligence reports from the south of strange gringos encouraging Mexicans take up arms against the United States. As Herman mulled the situation, he knew he could expect no reinforcements from U.S. forces then focused on the war effort in Europe. In addition to the 10th Cavalry, Herman had at his disposal a detail of soldiers from the 35th U.S. Infantry Regiment, though the main body of that unit was preparing for deployment overseas. The U.S. commander ordered the remaining infantrymen to augment U.S. border agents in Nogales even as he watched with growing anxiety for signs of an impending attack in the scorching desert heat.

The bewildered man stopped in the middle of the street, unsure whether to turn back or continue into Mexico

Around 4 p.m. on August 27 carpenter Zeferino Gil Lamadrid set out from a worksite on the U.S. side of Ambos Nogales bound for home. He carried a large parcel as he made his way across International Street toward the Mexican side. On high alert due to rumors of the expected attack, U.S. Customs Inspector Arthur G. Barber ordered Lamadrid to stop and present his parcel for inspection. On the south side of the street Mexican Customs Officer Francisco Gallegos urged the carpenter to disregard the Americano’s order and continue into Mexico. Barber then drew his revolver and ordered Lamadrid to halt. The bewildered man stopped in the middle of the street, unsure whether to turn back or continue into Mexico.

Seeking to convince Lamadrid to return to the United States for inspection, U.S. Army Pvt. William H. Klint, who was backing Barber, raised his M1903 Springfield. Someone fired a shot, each side later blaming the other. On hearing the report, Lamadrid dropped to the ground, believing he was the target of gunfire. Thinking the carpenter had been shot, Gallegos drew his pistol and fired, severely wounding Klint in the face. Barber and Cpl. William Tucker returned fire, killing Gallegos and another Mexican official. Responding to the gunfire, Mexican soldiers and citizens alike started pouring toward the border. In the meantime, Lamadrid scrambled to his feet and scampered safely into Mexico.

The shootings were the collective spark that ignited a powder keg of pent-up anger in the border town. The worst was yet to come.

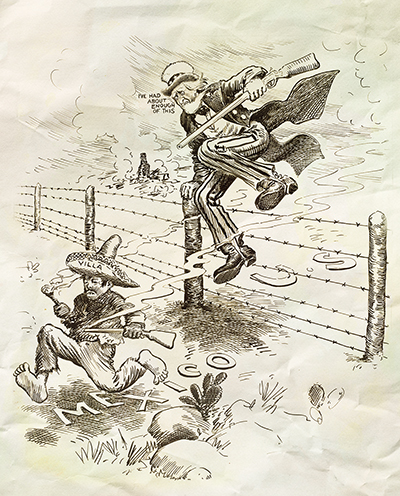

Tensions along the border had been on the rise since the 1846–48 war between the United States and Mexico. Under the terms of the subsequent Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo the Mexican government had been forced to cede some 529,000 square miles—the territory that comprises much of the present-day American Southwest. As instability and revolution continued to wrack Mexico in the early 20th century, incidents of cross-border raiding, crime and bloodshed increased in intensity and frequency.

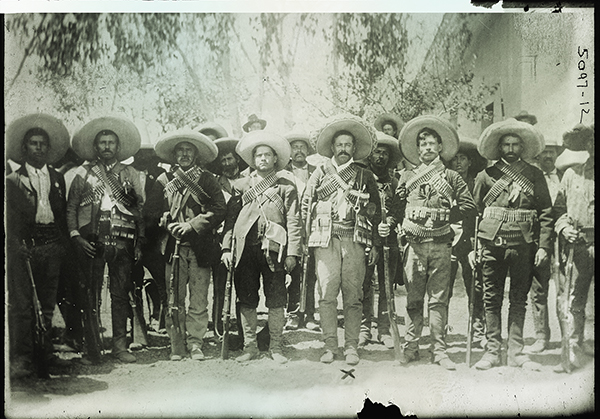

By March 1913 leading Mexican political rivals Venustiano Carranza, Pancho Villa, Emiliano Zapata and Álvaro Obregon had forged a tenuous alliance to battle troops loyal to Gen. Victoriano Huerta, who a month earlier had seized the Mexican presidency in a violent coup. In April 1914 American President Woodrow Wilson tipped the scales by sending a force of U.S. Navy sailors and Marines to occupy the port of Veracruz, Huerta’s supply base, after the general had foolishly detained a detail of sailors sent to shore to purchase fuel. The U.S. occupation stretched more than six months, enabling revolutionary forces to defeat Huerta’s ill-supplied troops and prompt the Mexican president’s resignation and self-exile.

To no one’s surprise, Carranza and Villa then turned against each other in the struggle for power. In October 1915, in an effort to stabilize the United States’ southern neighbor, Wilson recognized the ascendant Carranza as Mexico’s legitimate president. While he stopped short of providing direct military assistance, Wilson did place an embargo on arms sales to Villa and allow Carranza’s troops to travel by railroad through Texas to stand against Villa’s forces at the Sonoran border town of Agua Prieta.

Civilian spectators crowded the rooftop of the Gadsden Hotel and other buildings in nearby Douglas, Ariz., to watch the battle between Villa’s forces and the army of Carranza

On November 1, as U.S. troops deployed opposite Agua Prieta to prevent the conflict from spilling across the border, civilian spectators crowded the rooftop of the Gadsden Hotel and other buildings in nearby Douglas, Ariz., to watch the battle between Villa’s forces and the army of Carranza, ably led by Gen. Plutarco Élias Calles. That afternoon Villa—whose men outnumbered those of Calles more than 2-to-1—opened an artillery barrage that detonated many of the land mines placed around Calles’ entrenched positions. As darkness fell, Villa launched several feints against Calles’ defenses in preparation for a massed cavalry assault.

On signal just after midnight thousands of Villa’s horsemen thundered toward the enemy trenches. Before the cavalrymen reached Calles’ lines, however, two searchlights pierced the darkness, illuminating the riders for defending machine-gunners. The ensuing slaughter, coupled with subsequent mass desertions, threats of mutiny and supply problems, virtually eliminated Villa’s army as a credible force. Although it’s unclear whether the searchlights belonged to the Americans or Carranza’s forces, it is likely the United States provided help with the illumination. Enraged at what he regarded as American treachery, Villa was determined to exact revenge.

As the rebel leader withdrew into the mountainous interior of Chihuahua to rebuild his army, a different group of Mexican insurgents launched what amounted to a race war in south Texas (see “Bloodshed in ‘Magic Valley,’” by Mike Coppock, online at HistoryNet.com). Bound together by a revolutionary manifesto called the Plan of San Diego, these Sedicionistas sought to unite Mexicans, Mexican-Americans, American Indians and blacks in a guerrilla war to murder every Anglo male over age 16 and reclaim all the territory lost in the Mexican War. The rebels also targeted any Tejanos (Texans of Hispanic descent) unwilling to join them. The shadowy group launched some 30 raids against ranches, railroads, telegraph lines and other targets in the border region, killing nearly two dozen U.S. citizens. In one particularly gruesome incident raiders captured, tortured and decapitated an unfortunate U.S. Army soldier, displaying his severed head atop a pole along the border.

Reaction to the Plan of San Diego raids was swift and fierce. Texas Rangers, local lawmen and vigilantes rounded up and summarily executed any Mexican male thought to be associated with the movement, until the U.S. Army stepped in to put a damper on the violence. While the Plan of San Diego bandits faded away or were killed, the raids and the bloody reaction to them further inflamed hatred and distrust along the border.

Weakened, but not defeated, Villa’s forces emerged from hiding and on Jan. 10, 1916, seized a train near Chihuahua City, Mexico. Aboard were American miners returning to work U.S.-owned properties in the region on Carranza’s assurances of their safety. Ordering all passengers from the train, the raiders pulled aside 17 of the Americans and executed them on the spot; one survived to spread word of the attack. Two months later Villa committed a far bolder act of vengeance for U.S. complicity in his defeat at Agua Prieta.

Shortly after 4 a.m. on March 9 the rebel leader led an estimated 500 mounted guerrillas in a well-coordinated, multipronged cross-border assault against Columbus, N.M., and the nearby U.S. Army post of Camp Furlong. In the ensuing raid Villa’s men set much of the town on fire. Fighting side by side, the townspeople and soldiers managed to repulse the raiders, but not before some eight U.S. troops and 10 civilians were killed. The citizen-soldier army in turn killed upward of 80 Villistas, whose bodies were later stacked and burned.

News of the Columbus raid prompted nationwide outrage, followed by widespread demand for action. Heeding the call, within days Wilson placed U.S. Brig. Gen. John J. Pershing in command of a large expeditionary force (ultimately numbering some 10,000 men) with orders to pursue and apprehend Villa. Although Pershing kept the raiders scattered and on the run, Villa himself eluded capture, and cross-border raids continued to plague the Southwest. By August the president had called up more than 140,000 National Guards troops to secure the southern border. Finally, in January 1917, as events in Europe demanded his attention, Wilson recalled Pershing’s troops and ended the punitive expedition into Mexico.

A month later U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom Walter Hines Page received a copy of an intercepted telegram from Arthur Zimmermann, a high-level civil servant of the German Foreign Office in Berlin, to the German Embassy in Mexico City. The Zimmermann Telegram, as it came to be known, directed German Ambassador Heinrich von Eckardt to offer financial support to the Carranza government in exchange for hostile action against the United States. German agents in Mexico were already seeking to foment and organize Mexican attacks.

The revelation of the telegram coincided with the announcement of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s decision to resume unrestricted submarine warfare, which the German Foreign Office realized would draw the Americans into World War I. Wilson, who had steadfastly maintained the neutrality of the United States in the European war, was forced to yield to a popular wave of anger against German provocations. Accordingly, at the president’s urging, Congress declared war on Germany on April 6.

Pershing, since promoted to major general, was given command of the American Expeditionary Forces. As he worked to muster almost every available Army unit into the woefully unprepared AEF, U.S. forces along the Mexican border were stretched thin.

To make matters worse, that New Year’s Eve in Ambos Nogales border sentry Pvt. John Andrews of the 35th Infantry shot and killed off-duty Mexican customs agent Francisco Mercado as the latter attempted to cross into the United States. Mexican witnesses claimed that Mercado, who had ignored three separate warnings from Andrews, didn’t understand English. The shooting sparked a riot before U.S. and Mexican officials intervened. On March 22, 1918, in separate incidents, a U.S. cavalryman on patrol in Douglas was shot by a mounted gunman on the Mexican side of the border, and an unidentified Mexican was shot at the border crossing in Nogales after failing to heed a U.S. soldier’s order to halt. Cross-border hostility grew more intense by the day. Five months later the cork would pop.

No sooner had the smoke cleared from the border gunfight in Ambos Nogales on Aug. 27, 1918, than a hail of concentrated fire erupted from the south side of town, as Mexican soldiers and armed civilians advanced on the international line. Much of the firepower came from entrenched machine guns and sniper holes in the surrounding Sonoran hills, suggesting the Mexicans had been preparing to mount a full-scale attack.

As the Mexican riflemen advanced, Lt. Oliver Fannin and some 20 enlisted troops of the 35th Infantry threw together a stubborn defense. Fannin would receive the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions, as well as a testimonial from 33 of the leading U.S. citizens of Nogales. “Lt. Fannin hurried to the boundary line the reserve of the guard,” it read in part, “and taking position, he stood off the attack until the garrison could be brought to the line.”

On hearing the gunfire, Col. Herman phoned in an alert to subdistrict headquarters and raced to Ambos Nogales in his staff car to assume command. Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry from nearby Camp Stephen D. Little soon arrived at the border on horseback or in whatever motor vehicles were available. Herman understood the key to any effective defense of the border was possession of the hills to the east and west, which offered clear fields of fire into both sides of town.

Much of the firepower came from entrenched machine guns and sniper holes in the surrounding Sonoran hills, suggesting the Mexicans had been preparing to mount a full-scale attack

Herman first ordered Capt. Roy V. Morledge, commander of the 10th Cavalry’s Troop A, to lead a detachment of dismounted cavalrymen into the Mexican district. Taking fire from the surrounding hills and urban snipers, the troopers took cover in a building just south of the border. “It seemed as though everybody in Nogales was shooting from the windows toward the border,” Morledge recalled. The men soon realized they had taken refuge in the Concordia Club, a local house of ill repute. On recognizing a familiar customer, one of the “frightened señoritas” exclaimed, “Sergeant Jackson, are we all glad to see you!”

On orders from Herman, Morledge launched an assault against a Mexican position on the heights south of town, directing his force up the hillside in squad rushes. After dislodging the defenders, Morledge assessed his casualties—just five men wounded. The Mexicans weren’t as fortunate. “I hope we only hit those who were shooting,” the captain noted in his after-action report. “But there were a lot of bodies lying around.”

Herman next ordered Troop C of the 10th Cavalry, under Capt. Joseph D. Hungerford, to take and hold Reservoir Hill, a ridgeline to the southeast from which entrenched Mexican forces were laying down a withering fire. As he led his troopers in a dash up the scrub-covered hillside, Hungerford was killed by a bullet through the heart. First Sgt. James T. Penny took command, driving the Mexicans from their positions.

As the Americans advanced to take Titcomb Hill, another hilltop vantage, the men of the 35th Infantry supported troopers of the 10th Cavalry. Wounded in the right forearm early in the attack, Troop F commander Capt. Henry Caron was carried to safety by 1st Sgt. Thomas Jordan, who took command of the assault force. Two Americans were killed before the soldiers managed to dislodge Mexican defenders and occupy the hilltop.

Hearing of the battle on the border, individual American soldiers from the surrounding region made their way piecemeal to town. One 10th Cavalry trooper arrived on a horse riding bareback and wearing nothing but a hospital gown. Dismounting at the camp ordnance depot, the soldier practically begged for a rifle and ammunition. The quartermaster sergeant provided both, though not before having the man sign a receipt for the weapon. Another quartermaster soldier, Pfc. James Flavian Lavery, would receive the Distinguished Service Cross for “braving the heaviest fire, repeatedly entering the zone of fire with his motor truck and carrying wounded men to places of safety, thereby saving the lives of several soldiers.”

Tenth Cavalry Lt. William Scott was riding toward Ambos Nogales on a motorcycle when the battle broke out. Apparently familiar with the sandy desert trails around town, Scott navigated through the brush to a hillside offering a clear field of fire into the Mexican district. Armed with a .45-caliber pistol and a lever-action Winchester rifle, Scott engaged in solitary countersniper fire, picking off unsuspecting Mexican gunmen until the battle was over.

Although U.S. forces held most of the high ground and managed to establish a rooftop machine-gun position, fighting raged throughout Ambos Nogales well into evening. Civilians on both sides joined in the fray, either out of sheer animosity or in self-defense. On the U.S. side Pat Shannon—the daughter of a Chicago doctor, who worked as a pianist at the local theater—gamely loaded ammunition for two civilians firing from the windows of her hotel room. Customs officer Gaston Reddoch armed himself with a wounded soldier’s rifle and returned fire until mortally wounded in the neck by a sniper’s bullet. He was the only known U.S. civilian killed in the battle.

As the casualties mounted, Mayor Félix Peñaloza of Nogales, Sonora, tied a white handkerchief to the end of his walking stick and rushed into the streets. While pleading with his fellow citizens to end the bloodshed, the 52-year-old was struck down by gunfire. Bystanders carried the mortally wounded mayor to a nearby pharmacy, where he died within minutes.

Amid the chaos the U.S. and Mexican consuls, Herman and various other civil and military officials somehow managed to communicate with one another and eventually coordinate a cease-fire. On arrangement at 7:45 p.m. Sonoran officials in Nogales had white flag flown from their prominent customs house, and Herman ordered his troops to put up their guns.

The respective representatives met in an open plaza near the border, despite the risk posed by random potshots. “A sniper’s bullet cut off a small limb of a tree that fell pretty close to me,” recalled Lt. Fannin, who served as Herman’s aide at the meeting. “I felt like diving into a big ditch that was close to us.” Herman, who had suffered a bullet wound to the right thigh, demanded the Mexicans surrender and wholly disarm, but the diplomats negotiated a more amenable cessation of hostilities. Though sniper fire persisted through the night, the Battle of Ambos Nogales was over.

After conducting an investigation into the causes of the incident, Mexican and U.S. officials opened negotiations to re-establish peace in the border area. Hostilities flared briefly in late August, after an American trooper wounded by sniper fire retaliated by wounding a Mexican soldier. But cooler heads prevailed, containing the incident.

In the final tally the U.S. Army had suffered five killed and 29 wounded during the fighting in Nogales. Mexican casualties were estimated at 129 killed (including 30 federal troops) and some 300 wounded. According to U.S. intelligence reports, the bodies of two German agents also turned up in the aftermath of the fighting. Their identities were not recorded, nor were the papers found on them preserved, but it is likely they had helped incite hostilities.

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of the Battle of Ambos Nogales was a mutual agreement to construct a 2-mile-long border fence down the middle of International Street. In the ensuing decades the fence has grown into a substantial barrier. Today it serves to contain any lingering resentment or hostility, helping to keep the peace between uneasy neighbors. MH

Retired Army Brig. Gen. P.G. Smith—who once served on border security missions near Nogales, Ariz.—teaches counterterrorism strategy at Nichols College in Dudley, Mass. For further reading he recommends The Hunt for Pancho Villa: The Columbus Raid and Pershing’s Punitive Expedition, 1916–17, by Alejandro M. de Quesada, and U.S. Army on the Mexican Border: A Historical Perspective, edited by Celio Broggini.