During the spring of 1970, there was a threat to President Richard Nixon’s plan to end the war. In June 1969, he had announced an exit strategy focused on “Vietnamization,” a program to gradually transfer all of the war’s military operations to the South Vietnamese. At the same time, Nixon announced the beginning of phased U.S. troop withdrawals. Vietnamization was designed to strengthen the Army of the Republic of Vietnam and bolster President Nguyen Van Thieu’s government so the ARVN could stand on its own against the communist aggression from North Vietnam. At that point, all U.S. troops could be sent home.

On Aug. 15, 1969, the Nixon administration issued a new mission statement to Gen. Creighton Abrams, the head of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, in charge of all U.S. combat operations in South Vietnam. Nixon directed Abrams to provide “maximum assistance” to strengthen the armed forces of South Vietnam; to increase support for the “pacification” program (helping rural villages with social services, income-generating agriculture and security to build support for the Saigon government); and to reduce the flow of enemy supplies down the Ho Chi Minh Trail through Laos and Cambodia. Those two countries were technically neutral, but the NVA and Viet Cong had used them to establish “sanctuaries,” bases of troops and supplies used to launch attacks on South Vietnam.

The first U.S. withdrawals began in July 1969, when 25,000 troops departed, followed by 40,000 in December and 50,00 in spring 1970 through April. Meanwhile, the North Vietnamese leadership in Hanoi continued its long war of attrition, supported by the sanctuaries in Cambodia and Laos. Abrams became concerned that the American troop drawdown was occurring at a faster pace than the program to improve the South Vietnamese army.

Something had to be done to provide more time for the South Vietnamese to get their act together before U.S. troop levels were too low to provide significant assistance. In late 1969, Abrams proposed a limited operation to strike the communist sanctuaries in Cambodia. That idea had been proposed before but was disapproved every time it had been brought up.

Defense Secretary Melvin Laird and Secretary of State William Rogers were adamantly opposed to a U.S.-ARVN ground operation in Cambodia. They thought it would be political suicide to widen the war. Soon, however, events in Cambodia convinced Nixon that he had to send in ground troops—a decision that sparked a firestorm at home as many Americans, particularly those on college campuses, did indeed see the attacks as a widening of the war. Before the unrest ended, Congress would make moves to reduce Nixon’s power and four students would be dead at Kent State University in Ohio.

Cambodian Prime Minister Lon Nol overthrew the government of Prince Norodom Sihanouk in Phnom Penh in a bloodless coup on March 18, 1970. He assumed power as head of state while the prince was traveling outside the country. Nol, a strong anti-communist, closed the port of Sihanoukville to communist supplies and demanded that North Vietnam remove its troops from Cambodia. Hanoi refused and launched an offensive against Cambodia’s army. The North Vietnamese Army and its communist allies in Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge, quickly seized large portions of the eastern and northeastern parts of the country, advancing to within 20 miles of Phnom Penh. Nol requested assistance from the United States.

With Nol’s government in peril, Nixon reacted quickly to try to save “the only government in Cambodia in the last 25 years that had the guts to take a pro-Western stance.” Nixon had already ordered the secret bombing of communist sanctuaries in Cambodia in Operation Menu, which began March 18, 1969, and was exposed by The New York Times on May 9, 1969.

It became clear that bombing alone would not save Cambodia. Nixon asked the Joint Chiefs of Staff for a course of action. He got a range of options, including a naval quarantine of the Cambodian coast, more U.S. and South Vietnamese airstrikes, and a ground invasion along the lines of Abrams’ suggestion. The president chose a combined American-South Vietnamese ground attack in Cambodia to relieve the pressure on Nol’s troops, eradicate communist sanctuaries and destroy the headquarters of COSVN, the Central Office for South Vietnam, which coordinated communist political and military activities in lower South Vietnam and Cambodia. COSVN was thought to be somewhere in eastern Cambodia.

The joint U.S.-ARVN operation was drawn up as a limited incursion for a specific period of time, rather than a full-scale invasion. Ideally, it would eliminate the cross-border threat and buy time for Nixon’s Vietnamization and troop withdrawal policies. As a bonus, a good performance by ARVN soldiers would demonstrate the progress of Vietnamization.

The Cambodian operation, set for late April and early May, was directed by Lt. Gen. Michael Davison, commander of II Field Force, the organization in charge of U.S. units around Saigon and throughout the Mekong Delta. The incursion involved 50,000 ARVN and 30,000 U.S. troops in the largest series of allied operations since 1967’s Operation Junction City in the same part of South Vietnam.

The operation focused on two areas: the Fishhook, a piece of Cambodia that juts into South Vietnam about 50 miles northwest of Saigon; and farther south the Parrot’s Beak, a part of the border just 40 miles from Saigon. Those areas had fallen under the control of North Vietnamese forces, which had set up sanctuaries within easy striking distance of Saigon and other key South Vietnamese installations.

The Cambodian Incursion was divided into three separate major operations:

- The main attack would be Toan Thang (“Total Victory”), conducted by U.S. II Field Force and ARVN III Corps, which operated in Saigon and the provinces immediately to the north. This attack would hit Fishhook and Parrot’s Beak.

- Binh Tay (“Tame the West”), a supporting attack conducted by U.S. I Field Force and ARVN II Corps, based in South Vietnam’s Central Highlands, would strike enemy areas across the border from Pleiku and Ban Me Thuot.

- Cuu Long (“Mekong”), conducted by ARVN IV Corps in the Mekong Delta, would clear the banks of the Mekong River toward Phnom Penh.

The attack force for Toan Thang consisted of 10,000 Americans and more than 5,000 South Vietnamese. U.S. forces included the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), the 25th Infantry Division and the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment. South Vietnamese forces involved elements of the 1st Armored Cavalry Regiment, one armored cavalry squadron from the 5th and 25th divisions, an infantry regiment from the 25th Division, the 4th Ranger Group and the 3rd Airborne Brigade.

The plan called for a pincer movement in the Fishhook to trap units of the NVA 7th Division and a Viet Cong unit. Tanks and armored cavalry fighting vehicles from the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment would drive into Cambodia from the east and southeast while the 1st Cavalry Division attacked from the west. Meanwhile, the ARVN 3rd Airborne Brigade would be inserted at three positions to the north of the Fishhook to block enemy escape routes and then move south to link up with the 11th Armored Cavalry and 1st Cavalry Division. At the appropriate time, heliborne forces from the 1st Cavalry would land in the enemy’s rear to trap the 7th NVA Division. As the U.S.-ARVN forces moved through the area, they were to destroy enemy bases, fortifications and supply caches.

Col. Carter Clarke, commander of the 1st Cavalry Division’s 2nd Brigade, described the main objective to a reporter this way: “We’re not body counters on this operation, we’re cache counters.”

The planners decided that before the Fishhook attack, ARVN III Corps commander Lt. Gen. Do Cao Tri, one of the most dynamic and aggressive South Vietnamese generals, would lead 8,700 troops from the 5th and 25th Infantry divisions, along with four ranger battalions and four armored cavalry squadrons, into the northern shoulder of Parrot’s Beak to destroy sanctuary base areas 706 and 367.

South Vietnamese forces would then turn west to clear the rest of the Parrot’s Beak, seize the town of Svay Rieng and hit Base Area 354 to the north. American advisers would accompany the South Vietnamese to assist with logistics, artillery fire and close-air support from planes and armed helicopters, but the fighting would be done by the ARVN. Nixon hoped that aspect of the operation would “be a major boost to [South Vietnamese] morale” and prove the efficacy of Vietnamization.

Operation Toan Thang 42 began at 7 a.m. on April 29. Tri’s forces encountered enemy resistance almost immediately but continued to advance, supported by artillery and aircraft. As ARVN forces approached Svay Rieng, the North Vietnamese withdrew from Parrot’s Beak, while continuing to fire on the South Vietnamese. During the first three days of the operation, the South Vietnamese killed more than 1,000 communist soldiers and captured over 200, while suffering 66 ARVN troops killed and 330 wounded. They destroyed 100 tons of ammunition and 90 percent of the rice enemy forces had hidden in the area.

On April 30, as South Vietnamese and U.S. troops crossed into Cambodia, Nixon announced in a 9 p.m. television address that the attacks were being made in response to North Vietnamese “aggression” and the troops would be withdrawn as soon as they had destroyed communist bases in the area. He stressed that the operation was “not an invasion.” American and South Vietnamese forces would not push farther than 35 miles into Cambodia and would pull back once their goals had been accomplished, Nixon said.

Brig. Gen. Robert Shoemaker, assistant division commander of the 1st Cavalry Division, began the main attack’s second phase, Toan Thang 43, also known as Rock Crusher, on May 1 to clear the Fishhook. In the early morning hours, a massive artillery bombardment and strikes by 36 B-52 Stratofortress bombers pounded the area. After the bombardment, U.S. Army helicopters inserted paratroopers from the South Vietnamese 3rd Airborne Brigade into two landing zones north of the Fishhook.

At the same time, elements of the ARVN 1st Armored Cavalry Regiment drove across the border toward the town of Snuol, at the junction of routes 7 and 13. The South Vietnamese cavalrymen linked up with the ARVN paratroopers and formed two blocking positions to prevent an enemy escape.

Elsewhere, scout helicopters from the 1st Cavalry Division’s 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry, “screened forward” of the ground attack forces’ line of departure to search for enemy units, and behind them the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment and the 3rd Brigade of the 1st Cavalry launched twin thrusts into Cambodia. The armored regiment, on the right, attacked the southeastern edge of the Fishhook, while the 3rd Brigade on the left moved north from Katum, South Vietnam. The morning bombardment had done its job. The cavalrymen encountered only sporadic contact as they advanced.

To the north, U.S. helicopters airlifted two South Vietnamese airborne battalions from the 3rd Airborne Brigade to landing zones inside Cambodia. Enemy resistance was light. Over the next three days, the South Vietnamese airborne battalions moved out from their landing zones in the north to cut off the enemy’s retreat, while the U.S. cavalry’s 3rd Brigade pushed further into Cambodia.

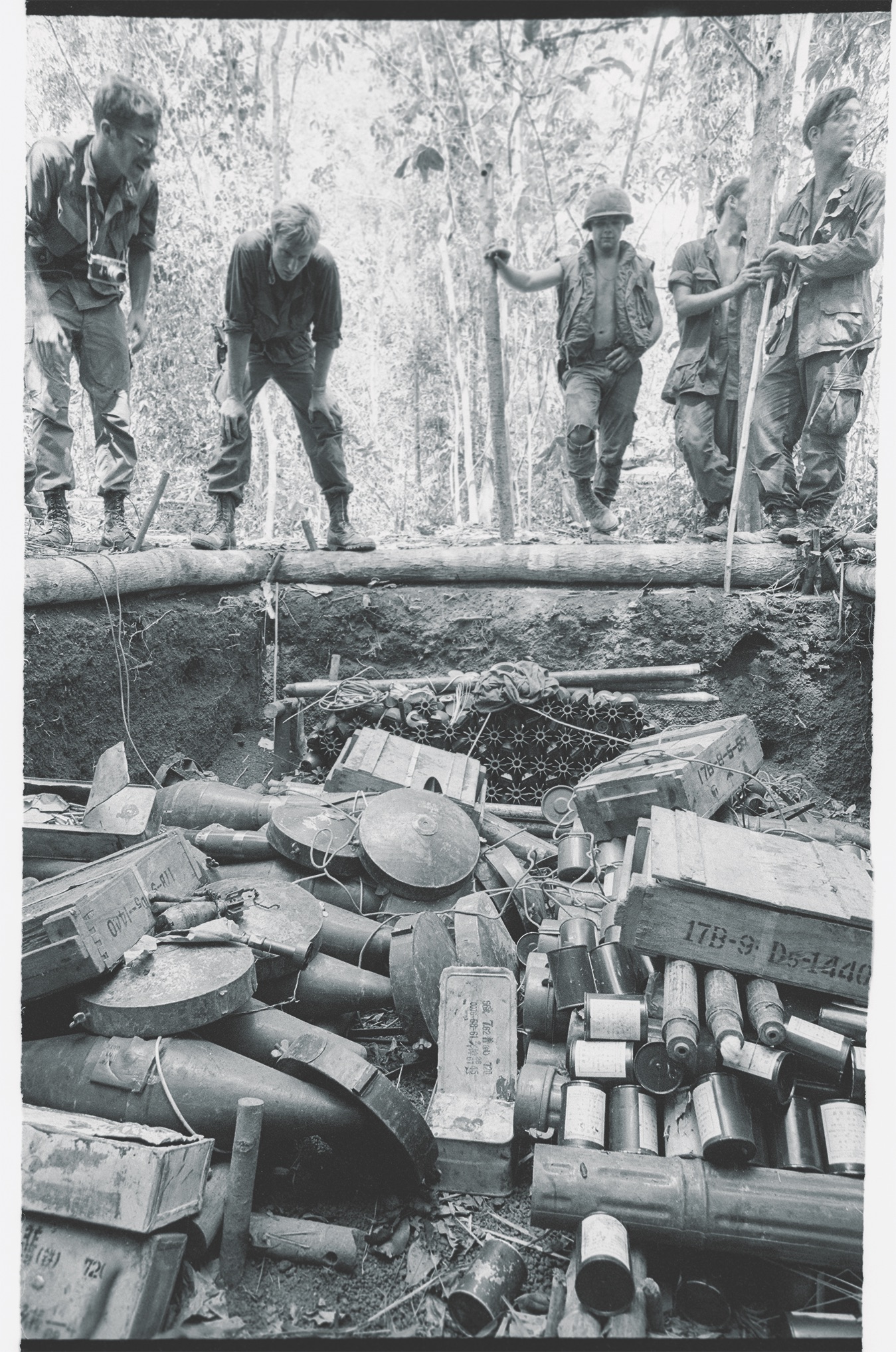

On May 3, an aerial scout from the 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry, discovered a large logistics center south of Snuol along Route 7 just north of Base Area 352. The 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry, was dispatched to check it out. The site was apparently the main base for the NVA 7th Division, and American soldiers soon dubbed it “the City.” U.S. troops discovered large stashes of supplies hidden in the heavily jungled area. They found some caches by literally stumbling over them, one company commander explained later. “A 140-ton arms and ammunition depot, for example, was found when a soldier tripped over a piece of metal covered with dirt,” he said. “The metal covered a hole, an entrance to a mammoth cavern.”

A thorough search of Area 352 revealed that it encompassed 3 square miles and contained more than 500 log-covered bunkers, along with assorted other structures, including storage sheds, truck repair facilities, hospitals, a lumber yard, 18 mess halls, and a chicken and pig farm. The cavalrymen nabbed 171 tons of munitions and 38 tons of rice. Much of the loot was moved to South Vietnam, and the stuff that could not be transported was destroyed in place.

While the 1st Cavalry Division troopers scoured the City, the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment continued to move rapidly northward toward Snuol. On May 5 the armored vehicles came to three bridges destroyed by the retreating enemy. The vehicles forded two of the streams but had to halt while engineers built a pontoon bridge over the northernmost waterway.

As the American troopers continued toward Snuol they encountered delaying tactics from small enemy units. Closer to town, they were hit with intense fire from NVA fortifications. Col. Donn Starry, the regiment’s commander, was wounded by grenade fragments and evacuated.

Airstrikes were requested late in the afternoon and continued the next day, reducing the town to rubble.

The morning of May 6, the 11th Armored, now commanded by Lt. Col. Grail Brookshire, entered Snuol. The NVA troops had withdrawn, leaving behind 150 of their dead. After the town was secured, Brookshire told reporters: “We didn’t want to blow this town away, but it was a hub of North Vietnamese activity and we had no choice but to take it.”

That same day, U.S. and South Vietnamese forces made three more attacks into Cambodia. In the first, Operation Toan Thang 44 (Bold Lancer), the 1st Brigade, 25th Infantry Division, moved southwest of the Fishhook into a part of Cambodia called the “Dog’s Head,” where it searched Base Area 354. The Americans killed 300 North Vietnamese and seized more than 200 tons of rice and many individual and crew-served weapons, as well as ammunition and other supplies before withdrawing back into South Vietnam.

In follow-on operation Bold Lancer II, which began May 15, the 1st Brigade returned to Cambodia and moved into the Fishhook to clear Base Area 353. The infantrymen were joined by units of the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment and the South Vietnamese 8th Airborne Battalion. Simultaneously, the 2nd Brigade of the 25th Infantry Division was operating in Base Area 707 to the west in the Dog’s Head. By the time Bold Lancer concluded in June, the Americans had captured 850 weapons, 45 tons of ammunition, 1,500 tons of rice, 56 vehicles and more than 6 tons of medical supplies.

The second thrust in Cambodia on May 6 was Operation Toan Thang 45. The 2nd Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division, attacked Base Area 351 north of the Fishhook. After several days of heavy fighting, the brigade discovered the largest enemy cache of the war. The facility, nicknamed “Rock Island East” after the U.S. Army arsenal in Illinois, contained 326 tons of ammunition, including large quantities of rockets and mortar rounds, more than a thousand Soviet-made 85 mm artillery shells and other ammunition.

The stockpile was stunning. To Capt. William Paris, “It was like Christmas.” The cache was so large that Army engineers had to build a road from the base to a nearby highway in South Vietnam to make it easier to haul away the enemy supplies. Still, there was so much war materiel that the engineers had to destroy a large part of it.

The third May 6 incursion was Operation Toan Thang 46. U.S. helicopters droped elements of the South Vietnamese 9th Infantry Regiment into Base Area 350, another site north of the Fishhook. Over the course of six weeks, South Vietnamese troops captured a surgical hospital and grabbed more than 100 tons of supplies, including 350 weapons, 20 tons of ammunition and 80 tons of rice. South Vietnamese forces counted 79 communist soldiers killed or captured, while 27 ARVN troops were killed.

On May 7, Nixon issued a directive that limited U.S. operations to a depth of 19 miles inside Cambodia and set a June 30 deadline for withdrawal of all U.S. troops from the country.

The four-phase Operation Binh Tay began on May 6. Attacking from Pleiku in the Central Highlands, the operation struck enemy bases in northeastern Cambodia using troops from the U.S. 4th Infantry Division and the South Vietnamese 22nd and 23rd Infantry divisions accompanied by an ARVN ranger group and the ARVN 2nd Armor Brigade.

In phase Binh Tay I, a planned helicopter landing of the 4th Infantry Division’s attached 3rd Battalion, 506th Infantry Regiment, in Base Area 702 was aborted because of heavy anti-aircraft fire. The next day the battalion was able to land, but several helicopters were shot down during the troop insertion. The division’s 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry Regiment, also landed in the area and joined the clearing operations. The infantrymen uncovered an abandoned NVA training camp with a 30-bed hospital and tons of supplies. Binh Tay I resulted in 212 communist dead and the capture of more than 1,000 weapons and 50 tons of rice.

Subsequent Binh Tay phases involved incursions by ARVN troops from Pleiku and Ban Me Thuot into base areas 701 and 740, leading to discoveries of more weapons and rice. All South Vietnamese troops stationed in the Central Highlands withdrew from Cambodia by June 27. Combined U.S. and South Vietnamese losses for Binh Tay were 43 killed and 18 wounded.

The third operation of the Cambodian campaign, Operation Cuu Long, began on May 9 when South Vietnamese forces in the Mekong Delta moved into Cambodia. The ARVN 9th and 21st Infantry divisions, the 4th Armored Brigade and 1st Marine Brigade, along with American advisers, cleared sanctuaries on both banks of the southern Mekong River. A force of 110 South Vietnamese navy vessels and 30 U.S. Navy craft sailed up the Mekong to Prey Veng to aid ethnic Vietnamese escaping to Vietnam, but the ultimate objective was to destroy Viet Cong vessels and patrols on the main water route between South Vietnam and Phnom Penh.

A follow-on operation, Cuu Long II, commenced on May 16 when South Vietnamese troops joined Cambodian government forces to retake the town of Kampong Cham, killing 613 communist troops while sustaining 36 killed and 112 wounded. Those forces launched Cuu Long III on May 24 to reestablish control in Kampong Speu and other towns south of Phnom Penh while continuing to evacuate more ethnic Vietnamese.

By the end of June 1970, all U.S. soldiers had withdrawn from Cambodia. The South Vietnamese soldiers, unconstrained by the time and geographic limitations imposed on U.S. forces by Nixon, continued cross-border operations for several weeks.

More than 80,000 U.S. and South Vietnamese personnel participated in the Cambodian Incursion. Abrams reported that they had destroyed over 40 percent of the enemy’s logistical support in Cambodia, including more than 11,700 bunkers. They had seized almost 23,000 individual weapons, 2,500 crew-served weapons, nearly 17 million rounds of small-arms ammunition, 200,000 rounds of anti-aircraft shells, 70,000 mortar shells, 143,000 rockets, 62,000 grenades, 435 vehicles, 6 tons of medical supplies and 700 tons of rice—enough to supply more than 50 communist battalions for over a year, according to intelligence estimates.

The major downside was the failure to find and destroy COSVN. But there had been doubt from the beginning about the existence of a discrete, consolidated central headquarters. One intelligence analyst had described COSVN as “a kind of a permanent floating crap game of Communist leaders,” a highly mobile, widely dispersed operation. Regardless, the headquarters, probably moved farther into the interior of Cambodia when the U.S.-ARVN forces crossed the border.

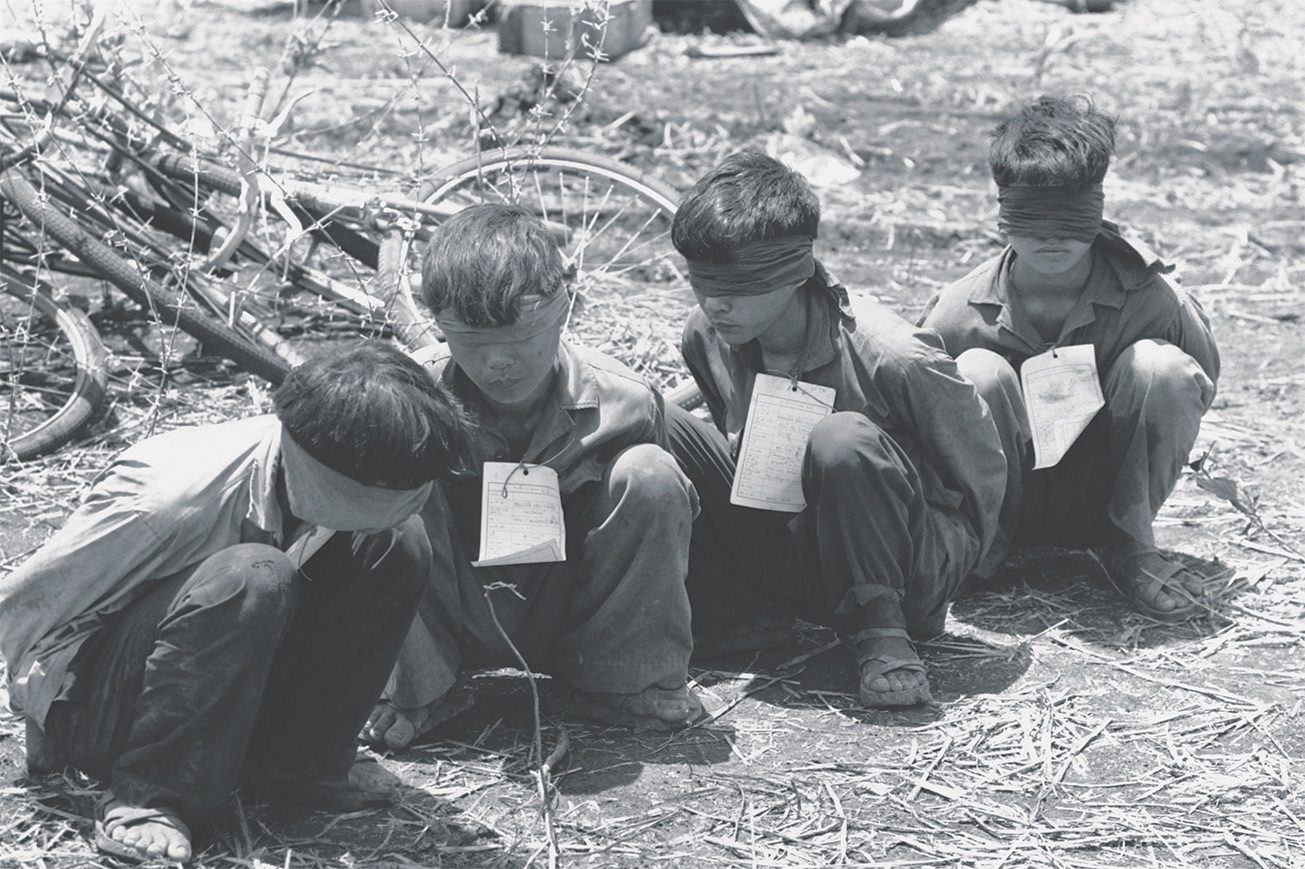

Officially, 11,349 enemy troops had been killed and more than 2,000 taken prisoner. More than 800 ARVN were killed, and 3,500 were wounded. U.S. losses in Cambodia included 344 killed and 1,592 wounded.

Nixon later called the Cambodian Incursion “the most successful military operation of the Vietnam War.” The pressure on Nol and his government had been alleviated. The fighting had inflicted heavy damage on the enemy’s logistical system and driven communist forces away from South Vietnam’s border. Nixon’s national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, said the operation had bought at least a year for South Vietnam to increase its combat capabilities and perhaps forestalled a major communist offensive for some time to come.

The Cambodian Incursion was the first real test of Vietnamization, and the South Vietnamese seemed to have passed it. ARVN troops, for the most part, performed very well, often operating beyond the range of American logistical and firepower support. However, some unit leaders still exhibited a lack of initiative and aggressiveness, and some formations were still too dependent on American advisers and U.S. fire support. Certainly, progress had been made, but it was clear more work remained to be done.

From a strictly military point of view, the Cambodian Incursion made sense and largely achieved its objectives, but the cost at home was high. The reaction to Nixon’s April 30 television address was swift and explosive. Many Americans had voted for Nixon based on his claim that he would bring the war to an end and achieve “Peace with Honor.” Now what was perceived as a needless widening of the battlefield energized the anti-war movement and increased opposition to the president and his handling of the war.

Protests erupted on university campuses across the country. On May 4, Ohio National Guard troops opened fire on Kent State students protesting the deployment of troops to Cambodia. The deaths of four students—and wounding of nine—shocked the nation. Two days later, police wounded four protestors at the University of Buffalo in New York. On May 15 city and state police opened fire on demonstrators at predominately black Jackson State College in Mississippi, killing two students in a confrontation attributed primarily to racial tensions.

In the escalating campus unrest, 30 ROTC buildings were set afire or bombed, and 26 schools experienced violent clashes between students and police. National Guard units were mobilized on 21 campuses in 16 states. A nationwide student strike brought walkouts and protests to 4 million students and 450 universities, colleges and high schools.

More than 100,000 people marched in Washington, D.C., on May 9 to protest the Kent State shootings and attacks in Cambodia. The demonstrators threatened to disrupt the government, and Regular Army troops were called out to maintain order and protect government facilities.

There was an immediate backlash in Congress. Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield, a Democrat from Montana, addressing the Cambodian operation, said, “There is without question a step-up in the fighting, which means in plain English, an escalation of the war.” Subsequently, Congress rescinded the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Gulf Resolution that President Lyndon B. Johnson and Nixon used as authorization for the war. That action was followed by congressional resolutions and legislative initiatives designed to limit the president’s power. Those attempts were unsuccessful, but they demonstrated the growing congressional resistance to Nixon and his policies.

Even though the Cambodian Incursion had provided some breathing room for Vietnamization to work and allow Nixon to pull out American troops at a gradual pace, the operation, ironically, increased domestic pressure to withdraw droops at a faster pace. Meanwhile, communist forces continued their fight without let-up. The Nixon administration was in a race to improve Saigon’s military forces before all U.S. troops were gone to enable the South Vietnamese to stop the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese by themselves. It was a race that the South Vietnamese could not win.